1. Background

Lymphohematopoietic malignancies in children, including leukemias and lymphomas, are among the most common pediatric cancers worldwide (1, 2). These malignancies often present with symptoms such as pallor, bleeding, fatigue, fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly, depending on the specific subtype (2, 3). Despite their aggressive nature, advances in diagnostic tools, risk stratification, and tailored therapeutic approaches — such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation — have significantly improved survival rates (4, 5). Early recognition and management of complications like tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) are critical to minimizing treatment-related morbidity and mortality, emphasizing the importance of multidisciplinary care in pediatric oncology (6).

The TLS occurs in tumors characterized by high growth rates, large tumor burden, or extensive dissemination, which are highly sensitive to cytotoxic therapy. It is commonly seen in Burkitt lymphoma, lymphoblastic lymphoma, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), particularly T-cell ALL with hyperleukocytosis. Rapid tumor cell destruction leads to the release of intracellular ions and molecules into the bloodstream, overwhelming the body’s metabolic and excretory systems, thereby causing the complex pathophysiology of TLS (7-9). Tumor lysis syndrome is classified into two types: (1) Laboratory TLS: Defined by specific metabolic abnormalities, including hyperuricemia, hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia, and hypocalcemia; (2) clinical TLS: Laboratory TLS plus clinical symptoms such as renal failure, cardiac arrhythmias, or seizures (6).

The TLS is a medical emergency requiring prompt treatment to prevent acute kidney injury (AKI), severe metabolic disturbances, and mortality. Interventions include hydration, alkalinization, and hypouricemic therapy to mitigate risks before initiating cytotoxic therapies (6). Despite its clinical significance, there is limited data on TLS in pediatric patients in Iran.

2. Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the incidence and consequences of TLS in pediatric lymphohematopoietic malignancies.

3. Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study evaluated pediatric patients diagnosed with lymphohematopoietic malignancies at Ali Ibn Abi Talib Hospital, Zahedan, from October 2014 to March 2019. The sample size included all patients with lymphohematopoietic malignancies during this period, totaling 93 after applying exclusion criteria. The study was approved by the University Ethics Committee (ethics code: IR.ZAUMS.REC.1396.131).

3.1. Data Collection

Data were collected using a standardized form, which included demographic information, tumor type, laboratory findings, AKI, and mortality. Patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for TLS were identified based on established guidelines, including laboratory and clinical parameters such as metabolic abnormalities and symptomatic presentations. The inclusion criteria were children diagnosed with lymphohematopoietic malignancies, aged 0 - 18 years, who underwent chemotherapy during the study period. Exclusion criteria included incomplete medical records or pre-existing renal dysfunction. Detailed clinical assessments, including baseline metabolic and demographic evaluations, were conducted for all participants.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics. Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests, and continuous variables were compared using independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, depending on the normality of the data. Multivariate regression analyses were conducted to adjust for potential confounders when evaluating associations between TLS incidence and clinical outcomes.

3.2. Definitions

3.2.1. Laboratory Tumor Lysis Syndrome

The presence of at least two metabolic abnormalities, including hyperuricemia, hyperphosphatemia, hyperkalemia, and hypocalcemia, or a 25% increase in potassium, phosphate, or uric acid, or a 25% decrease in calcium within three days before or seven days after the initiation of chemotherapy (10).

3.2.2. Clinical Tumor Lysis Syndrome

Laboratory TLS plus symptoms such as renal failure, seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, or sudden death (10).

3.2.3. Metabolic Criteria

Hypocalcemia: Calcium < 7 mg/dL

Hyperphosphatemia: Phosphate > 6.5 mg/dL

Hyperuricemia: Uric acid > 8 mg/dL

Hyperkalemia: Potassium > 6 mEq/L

3.2.4. Acute Kidney Injury

Defined by a serum creatinine elevation of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours or ≥ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, or urine output of ≤ 0.5 mL/kg/h for six hours (11).

4. Results

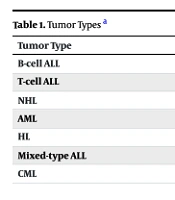

This study included 93 children with lymphohematopoietic malignancies. The mean age of the participants was 6.65 ± 4.42 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 66 males (71%) to 27 females (29%). Tumor types are shown in Table 1. The incidence of TLS was categorized into laboratory and clinical cases. Laboratory TLS was identified in 14 patients, accounting for 15.1% of the study population. Among these cases, four were associated with B-cell ALL, three with T-cell ALL, four with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), two with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and one with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Clinical TLS, a more severe manifestation, was observed in five patients (5.4%), including three cases of T-cell ALL, one case of B-cell ALL, and one case of NHL. These findings highlight the varying prevalence of TLS among different malignancies, underscoring the need for vigilance in high-risk patients.

The highest white blood cell (WBC) count was observed in a patient with CML (Table 2). The mean WBC count in patients with laboratory TLS was 90.34 ± 66.15 × 103/µL, which was higher than in non-TLS patients, who had a mean count of 59.12 ± 39.63 × 103/µL. After adjusting for potential confounders such as age, tumor type, and baseline renal function, multivariate regression analysis indicated that an elevated WBC count remained an independent predictor of TLS (adjusted odds ratio: 2.35, 95%, confidence interval: 1.12 - 4.91, P = 0.03).

Metabolic disorders were common complications among the study population. Hyperphosphatemia was the most frequently reported abnormality, affecting 33.3% of patients, followed by hyperuricemia, present in 29% of cases. Hypocalcemia was identified in 17.2% of patients, while hyperkalemia was the least common, occurring in 8.6% of cases. These metabolic disturbances underscore the critical need for close monitoring and timely intervention to prevent further complications in children with lymphohematopoietic malignancies.

Five cases of acute AKI were reported, with three requiring dialysis; however, no mortality due to TLS was observed in this study.

5. Discussion

Tumor lysis syndrome is a critical oncological emergency that affects both pediatric and adult populations. Prompt and appropriate management is essential to reduce morbidity and mortality. Without timely intervention, AKI, rapidly progressive renal failure, and severe metabolic disturbances can lead to fatal outcomes. Consequently, early diagnosis and identification of tumors with a high risk of TLS are of paramount importance, and numerous studies have explored this topic (12, 13).

The incidence of TLS in hematologic malignancies, as reported by Calvo, ranged from 3% to 26%, depending on factors such as the type of malignancy, antitumor treatment, early recognition, prophylactic measures, and patient characteristics (14). A study involving 788 adults and pediatric patients with acute leukemia or NHL demonstrated variations in TLS incidence based on laboratory versus clinical criteria: 18.9% versus 5%, respectively (15). Another study reported that, among 1,791 evaluable patients from the NHL-BFM 90 and 95 trials, 4.4% developed TLS, and 2.3% experienced oligoanuria (16). Cairo et al. documented an 18% incidence of TLS in children and adolescents with bone marrow (BM) ± central nervous system (CNS) mature B-cell NHL (B-NHL) treated with group C FAB/LMB therapy (17).

A study in Iran assessed TLS incidence in pediatric malignancies. Of 69 children with cancer, laboratory TLS was observed in 11.6% of patients, and clinical TLS in 2.9% of patients, both of whom had NHL (18). In our study, 15.1% of patients were diagnosed with laboratory TLS, and 5.3% with clinical TLS.

In a study conducted in Saudi Arabia, the incidence of TLS among children with ALL was reported at 19%. Among these, 93.3% exhibited laboratory TLS, and 6.7% had clinical TLS. Dialysis was required in 6.6% of cases, but no mortality was reported (19). Unlike the aforementioned study, which focused exclusively on ALL, our study examined TLS across all pediatric lymphohematopoietic malignancies. Of our participants, 72% had ALL, and 28% had other malignancies. Laboratory TLS was found in 15.1% and clinical TLS in 5.4%. The AKI was observed in 5.3% of patients, with 3.2% requiring dialysis. No TLS-related mortality occurred in our study.

A 2014 study by Mansoor et al., involving 317 children with hematologic malignancies, identified laboratory TLS in 11.4% of patients and clinical TLS in 8.5% of patients. Metabolic abnormalities included hyperphosphatemia (14.2%), hypocalcemia (13.9%), hyperuricemia (12.6%), and hyperkalemia (1.3%). The AKI occurred in 14.2% of patients. The study also noted significantly higher WBC counts in patients with TLS at the start of chemotherapy (20). In our study, patients with laboratory TLS had a higher mean WBC count than those without TLS.

A 2011 study by Sevinir et al. on patients with NHL and ALL reported hyperuricemia in 26.5% of NHL cases and 12.6% of ALL cases. The TLS was documented in 15.9% of NHL patients and 7.4% of ALL patients, with 7% of hyperuricemia cases requiring hemodialysis. No mortality was reported (21). In our study, the highest TLS incidence was observed in patients with B-cell ALL and NHL (28.5% each), surpassing the rates reported by Sevinir et al (21). Additionally, the need for hemodialysis was lower in our cohort (3.2%).

In the current study, high-risk cases were identified based on American Cancer Society criteria. Among these, 24 patients (25.8%) with B-cell ALL and 3 patients (3.2%) with AML were classified as high-risk. Of the 5 patients with clinical TLS, 2 belonged to the high-risk group, while 5 of the 14 laboratory TLS cases were similarly categorized.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that laboratory TLS occurred in 15% of lymphohematopoietic malignancies. However, potential sources of bias should be acknowledged. Selection bias may have occurred due to the single-center study design, potentially limiting the diversity of the patient population. Additionally, reliance on retrospective medical record reviews may have introduced information bias due to incomplete or inconsistent documentation. Given the clinical significance of TLS, close monitoring and preventative measures during treatment are crucial. The findings of this study may not be fully generalizable to all pediatric oncology populations due to its single-center design and the specific regional healthcare setting. Future multicenter studies are needed to validate these findings in more diverse patient populations.