1. Background

Asthma is a complex syndrome from interaction of genetic and environmental factors (1). In a child, the chance of developing an atopic illness is 50% when one parent has allergy and it is 66% when both parents are allergic (2). Environmental factors include everything surrounding a child inside and outside their home, day care center, diet, hobbies, and medication.

However, asthma has been associated with a wide range of risk factors. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated the relationship between asthma and maternal age (3), caesarean birth (4), time of starting solid food (5), type of diet (6) and obesity (7) as well as prenatal use of paracetamol (8) and antibiotics (9). The other identified risk factor is exposure to smoking in children (10). In contrast to these risk factors for developing asthma, breast milk feeding is considered protective against allergy (11). Rhinitis, sinusitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) often accompany asthma and can mimic asthma symptoms and aggravate the disease severity, known as co-morbid conditions (12). History of atopic dermatitis is important because the atopic march is mainly related to the incidence of asthma in the future (13).

2. Objectives

Common risk factors are infrequently studied simultaneously in children. Lack of such information justified the current study, which aimed at assessing the role of associated factors, including demographic data, maternal and prenatal confounding issues as well as housing- related factors in asthmatic children aged five to 15 years in southwestern Iran.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Shiraz, the capital of Fars province, in southwestern Iran with about 1.5 million inhabitants during year 2016. Children aged five to 15 years, who frequently referred to the Allergy outpatient clinics affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for visiting an allergist due to scheduled check-ups or having illness were selected. Asthma in all children was diagnosed by an allergist, according to the expert panel report 3 (14). Following approval of the study protocol by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (IR.SUMS.REC.1394.S462), a total of 737 children were enrolled in this study after informed consent was obtained from their parents.

A questionnaire was designed to collect information on the birth history of the children, the parents’ demographic data and information based on a review of related literature and the international study of asthma and allergies in children (ISAAC) (15). The questionnaire was categorized to three parts:

Part 1: Age, gender, birth place, type of delivery, birth date, birth weight, number of siblings, prematurity, blood group, types of feeding (breast fed or formula fed and duration of them), time of starting solid food, the occurrence of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, GERD, attending a day care center, documented food allergy, and adenoidectomy. The use of acetaminophen and taking this medicine at least once a month in the last 12 months, the age of taking the first dose of antibiotics, the presence of pet at home in the last 12 months, the hours of watching TV during the day, and using influenza vaccination was considered. The number of times eating fast food, fish, junk food, cola, fruit and vegetables including never, 1 to 2 and ≥ 3 times a week was asked.

Part 2: Age of the mother during pregnancy, parents’ education, mode of delivery, using iron by pregnant mother, information on the parents’ atopic history, and presence of a smoker at home.

Part 3: A home environment questionnaire was filled to obtain information about the type of dwelling, age of the building, damp stains, use of carpet, washing bed cover regularly, method of cooking, number of using vacuum cleaner in a week, carpets in the bedroom, and finding cockroaches during the previous year.

The collected data was statistically analyzed by SPSS version 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Frequency and percentages, No. (%) were used to describe the demographics, characteristics of maternal and prenatal factors, environmental factors, and atopic manifestations of the children. Descriptive statistical techniques were used to determine mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD).

4. Results

A total of 740 questionnaires were filled out even though three were excluded because of filling error. The mean age of children with asthma was 8.1 ± 2.7 years and their mean birth weight was 3.12 ± 0.57 kg. Table 1 presents the main demographic characteristics of children with asthma.

| Variable | No. (%), N = 737 | 95% CI for Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 494 (67) | 63.5 - 70.4 |

| Female | 243 (33) | 29.6 - 36.5 |

| Months of birth | ||

| Oct - Mar | 340 (46) | 42.5 - 49.8 |

| Apr - Sep | 397 (54) | 50.2 - 57.5 |

| Birth order | ||

| First born | 445 (60.4) | 56.7 - 63.9 |

| Second or more | 292 (39.6) | 36.1 - 43.3 |

| Preterm delivery < 37 weeks | ||

| Yes | 52 (7) | 5.3 - 9.1 |

| No | 685 (93) | 90.9 - 94.7 |

| Birth weight, kg | ||

| < 3.5 | 506 (68.7) | 65.2 - 72.0 |

| ≥ 3.5 | 231 (31.3) | 28.0 - 34.8 |

| Presence of siblings | ||

| 0 - 1 | 577 (78.3) | 75.1 - 81.2 |

| 2 or more | 160 (21.7) | 18.8 - 24.9 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| < 20 | 422 (81.5) | 78 - 85 |

| 20 - 25 | 75 (14.5) | 12 - 18 |

| > 25 | 21 (4.1) | 3 - 6 |

| Adenoidectomy | ||

| Yes | 71 (9.6) | 8 - 12 |

| No | 661 (90.4) | 87 - 92 |

The blood group and Rhesus factor (RH) distribution among 178 infants, who had identified blood groups included: O blood group in 72 (40.5%), A in 62 (34.8%), B in 33 (18.5%) and AB in 11 (6.2%) as well as Rh (+) in 95%, and Rh (-) in 5%.

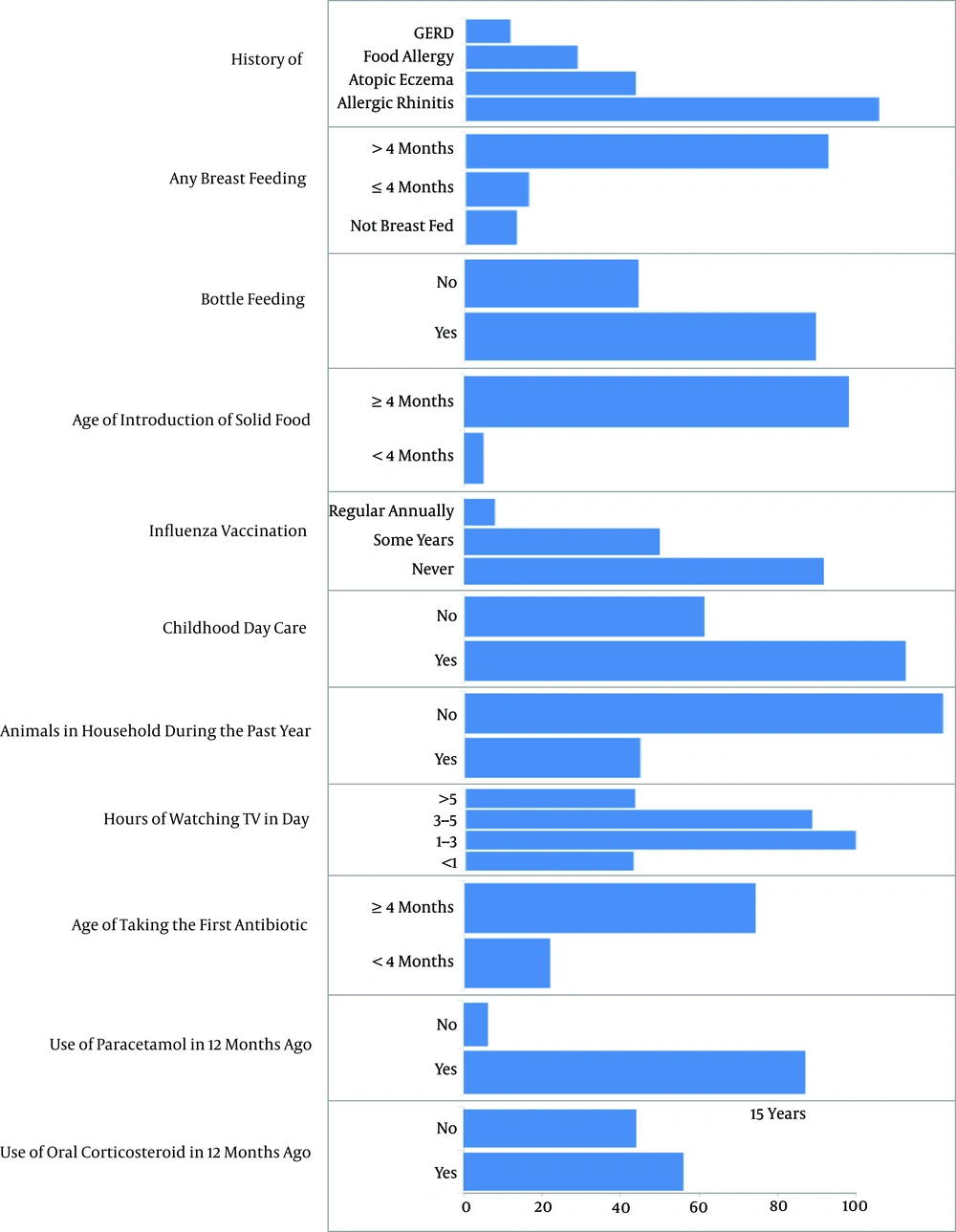

Frequency of other factors associated to asthma in children is shown in Figure 1 and Table 2. Among 596 children, who were school students, 187 were studying at private schools and 409 at public schools. Among 400 children, who attended day care centers, only 20 had an age of less than six months.

| Consumption of Foods in 12 Months Ago | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Fast food | |

| Never | 517 (70.1) |

| 1 - 2 times in week | 169 (22.9) |

| ≥ 3 times in week | 51 (7) |

| Fish | |

| Never | 389 (52.8) |

| 1 - 2 times in week | 309 (41.9) |

| ≥ 3 times in week | 39 (5.3) |

| Junk food | |

| Never | 391 (53) |

| 1 - 2 times in week | 241 (32.8) |

| ≥ 3 times in week | 105 (14.2) |

| Cola | |

| Never | 382 (51.8) |

| 1 - 2 times in week | 224 (30.4) |

| ≥ 3 times in week | 131 (17.8) |

| Fruits and vegetables | |

| Never | 57 (7.7) |

| 1 - 2 times in week | 204 (27.7) |

| ≥ 3 times in week | 476 (64.6) |

Table 3 shows the frequency of different factors in the family of children with asthma. The mothers’ mean age was 25.9 ± 5.9 years during pregnancy. Delivery was in approximately two-thirds of the children through vagina and one-third by cesarean section.

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Mother’s education level | |

| Illiterate | 12 (1.6) |

| Primary school | 271 (36.8) |

| High school | 294 (39.9) |

| Advanced | 160 (21.7) |

| Father’s education level | |

| Illiterate | 19 (2.5) |

| Primary school | 274 (73.3) |

| High school | 283 (38.4) |

| Advanced | 161 (21.8) |

| Maternal age, y | |

| < 25 | 290 (39.3) |

| 25 - 35 | (57.3) |

| > 35 | 25 (3.4) |

| Using iron during pregnancy | |

| Yes | 672 (91.1) |

| No | 65 (8.9) |

| Maternal job | |

| House worker | 671 (91) |

| Out worker | 66 (9) |

| Type of delivery | |

| Cesarean section | 437 (59.3) |

| Vaginal delivery | 300 (40.7) |

| Parental asthma | |

| Yes | 361 (49) |

| No | 376 (51) |

| Cigarette smoking | |

| Non-smokes | 520 (70.5) |

| Father smokes | 210 (29) |

| Mother smokes | 3 (0.5) |

Based on housing-related variables, 207 (28%) children with asthma were living in an apartment. The mean age of their building was 12.5 ± 13.1 years. The presence of cockroaches reported by the families during the previous year was 316 (42.9%) and home dampness was reported in 144 (19.5%). Having carpet is usual in all Iranian houses and all of them cooked with a gas stove. Washing the children’s bed covers was done in 507 (68.8%) regularly every one to two weeks. Five hundred and fifty (74.6%) families used vacuum cleaners one to two times a week, 118 (16%) more than two times, while five families did not use this electrical device. General insurance covered 655 (88.9%) children with asthma, among all.

5. Discussion

Asthma usually begins in early childhood and is associated with possible risk factors, including genetic, demographic, and environmental factors. This study showed asthma was more than two folds prevalent in males than females. Although males have a higher prevalence than females for developing asthma before puberty (16), an established single mechanism cannot explain this gender difference. The caliber of lung airways is smaller in males than females relative to their lung volume, which results in greater airway resistance and increased wheezing in males (17).

Although the occurrence of wheezing in children usually occurs together with a viral respiratory tract infection during the cold season, there was an association between months of birth in warm weather and the occurrence of asthma.

There was a significantly higher prevalence of asthma among children, who were the first child and also had a low number of siblings. Overcrowding at home due to a closer contact among people is associated with higher risk of viral respiratory tract infections, consistent with the hygiene hypothesis; early exposure to viral infections is a protective factor against asthma (18).

A new meta-analysis study found that premature babies reveal almost three times the risk of developing asthma than term infants when they become older (19); however, the rate of prematurity was low in this study.

Increased risk of childhood asthma with low birth weight has been identified in thirteen cohort studies on 1,105,703 individuals. Two suggested mechanisms are growing problems with lung development, and using many antibiotics in low birth weight infants cause a hypersensitivity to the outdoor environmental factors and result in an increased risk of asthma (20). In agreement with the current literature, the rate of low birth weight was found in about 70% of children with asthma.

Many studies have shown that obesity is a risk factor for asthma; the current research indicated that 4% of children had a high BMI. It is suggested that obesity may be a dependent risk factor for asthma in Iranian children. In the present study, children with asthma and BMI < 20 kg/m2 showed a significantly higher risk of asthma, consistent with greater chance of various diseases in undernourished populations in developing countries (7).

It was shown that adenoidectomy was associated with an increased risk of asthma, especially among young children, who had undergone an adenoidectomy due to recurrent otitis media (21). Nevertheless, according to researchers from the University of Chicago, IL, children with asthma can achieve better symptom control after adenoidectomy (22). It is important that physicians should consider the risk of adenoidectomy for development of asthma.

The relationship between ABO blood group and asthma is uncertain. Bijanzadeh et al. (23) demonstrated a lack of association between asthma and ABO blood group in South India. The current findings are consistent with those of Al-Shamma et al. (24), showing that asthmatic patients have a significant increase in O blood group.

This study found that medical history of co-morbidity conditions was common in children with asthma. In agreement with earlier studies, allergic rhinitis was recognized as the most common type of atopy among children with asthma (25, 26). This differs from studies conducted in Hong Kong and Sweden, which found that eczema is the most prevalent atopy in asthmatic patients (27, 28). Treatment of comorbidities, such as allergic rhinitis may decrease the possibility of developing asthma or acute exacerbation.

The coexistence of food allergy and asthma occur in 10% of children, and recent studies found that children with both food allergies and asthma have increased risk for severe asthma (29).

The high rate of exclusive breast feeding (89%) in this study can be attributed to the government’s efforts in the past few years to promote breast feeding. According to a recent research, exclusive breast feeding for up to six months can reduce asthma in early childhood (30), it was also shown that children, who were fed formula or solids during their first four months of life along with breast milk had a greater risk of asthma-like symptoms during the first four years.

When children with asthma develop influenza, they suffer more severe symptoms compared with non-asthmatic children (31). It is estimated that one third of asthmatic children are vaccinated on a regular basis (32); considering the very low vaccination against influenza, there is a need to encourage families in this regard.

If a child goes to day care center during the first months of life, she/he will be protected from asthma or recurring wheezing in subsequent years; moreover, when infants turned two years old, the result was not the same (33).

A study showed that the frequency of sensitization to animal allergens was 33% in children with asthma compared to 10% in the control group in this area (34). About 30% of the children with asthma kept animals at home; this refers to the fact that the rate of sensitization is similar to that of housekeeping in this study. Children, who watch TV for long hours are more likely to develop asthma, thus parents should try to stimulate their child to keep away from TV and encourage them to perform regular exercise (35).

A study reports that antibiotic use in the first year of life is related to little risk of developing asthma in early childhood and another study suggests that using numerous antibiotics in early life is more common among children with asthma (36, 37). Using paracetamol in the first years of life and development of childhood asthma is under inconclusive arguments (8). A reason for high use of paracetamol in this study was related to taking this drug after routine vaccination.

Two main causes of asthma exacerbation in children are refusal to use inhalational corticosteroid due the fear of potential adverse effects by parents and lack of awareness of correct inhaler techniques. More than half of the children had taken oral corticosteroid in the last 12 months; due to acute exacerbation of asthma, oral corticosteroid was recommended for five days or a shorter time (38).

Lifestyle changes including dietary habits can be a reason for increasing asthma (6). Consumption of fast food was not common in the children with asthma because a lot of Iranian mothers cook at home; meanwhile, drinking carbonated cola was popular. Although beneficial effects of natural anti-inflammatory products such as omega-3 in fish have been documented, the consumption of fish was low in children with asthma (39). There is a need to encourage awareness on the influence of diet on asthma through public health strategies.

General parental education and mother's employment do not influence the morbidity of asthma, yet holding well-organized educational programs about asthma for parents will provide better control of asthma (40). It appears that there is an association between asthma in children and age of mothers at period of delivery. Younger maternal age is associated with less stressful pregnancy, improved lifestyle, and greater number of siblings; these could be causes for decreasing risk of asthma (3). A study reported that low level of maternal iron during pregnancy is related to the risk of asthma and atopic sensitization in children (41). This study could not measure iron status of maternal serum, yet more than 90% of them used this supplement during pregnancy.

The observed prevalence of cesarean section in the current study was 60%; one reason is obstetrical indications, yet maternal request is a big problem that may cause long-term health problems. A cohort study on 411 Danish children with asthma reported that the chance of asthma by cesarean delivery was 2.18 compared to vaginal birth (42).

Parental asthma was common among the 361 children in the study. It has been suggested that epigenetic modification of DNA and exposure to environmental factors leads to development of different phenotypes of asthma (43). Postnatal exposure to smoking has been reported as a risk factor for later asthma in life (10). Various factors in the home environment, such as occupancy in an apartment unit, newer building, dampness, and cockroaches, were associated with development of asthma (44, 45). Carpet is a source of indoor allergens and dust; moreover, it is very popular in this country. Environmental control of allergens can significantly reduce asthma symptoms, such as vacuuming as well as weekly washing of the sheets and mattress.

The current findings should be interpreted considering the following limitations: clarifying a precise correlation between risk factors and development of asthma requires checking these factors in non-asthmatic children as the control group. This study was a cross-sectional analysis, in which the probable risk factors may change over time. Parents with asthmatic children were not recruited from private medical groups in this area.

5.1. Conclusions

Some risk factors, including male gender, product of cesarean section, first birth, low birth weight, adenoidectomy, and low number of siblings were common in children with asthma. Many children had more than one allergic disease, such as allergic rhinitis. Some factors, such as influenza vaccination and eating fish should be encouraged to reduce the morbidity of asthma. For clarifying a precise correlation between the risk factors and development of asthma requires other studies with a control group.