1. Background

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a prevalent psychiatric disease (1). This is a highly distressing disorder associated with poor quality of life (2). The disorder is categorized under obsessive-compulsive, and related disorders based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria and is characterized by persistent and intrusive preoccupation with perceived defects or flaws in one’s physical appearance. This leads to compulsive grooming, repetitive mirror checking, and reassurance seeking (3). The preoccupations are very time-consuming and usually difficult to be resisted or controlled (4). Body dysmorphic disorder is linked with anxiety, distress, cosmetic surgery, and suicide (5). Research has shown that about 80 percent of people with BDD repetitively check their appearance in mirrors, often for significant periods of time. The disorder is also associated with the risk of suicidal behaviors (1). Surveys indicate that BDD is not rare in patients with psychiatric disorders. A population-based survey in Germany reported a prevalence of 1.7% (6). Another research reported a prevalence of 0.7% among women between the age of 36 to 44 years in the US (7). The prevalence of BDD is even higher among the people referring to medical clinics such as dermatology. A great number of individuals with BDD seek cosmetic surgery (8). For example, in a survey among the individuals visiting a beauty clinic in Tehran, 33.3% had BDD symptoms (9). Furthermore, in a study conducted by Shaffi Ahamed et al. (10) in Saudi Arabia on female medical students (n = 365), it was found that 4.4 % of the students experienced BDD. In their study, skin appearance and body fat content were the most frequent body features of concern. A majority of individuals with BDD receive cosmetic treatment to improve their perceived defects (1). The disorder is often associated with other comorbidities, the most common of which is the major depressive disorder that usually presents after BDD. Social anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and substance-related disorder are also common (3). Other surveys have reported that about 10 % of the patients suffering from social phobia had BDD as well (11).

There have been several surveys in Iran on the prevalence of BDD, indicating that this is a relatively common condition. For example, in a study conducted on a sample population of Iranian orthodontic patients, 55 % suffered from BDD (12). In another study carried out among the individuals seeking cosmetic surgery in Tehran, the prevalence of BDD was 33 %, and the majority of patients were female (9). Regarding the lack of knowledge on the prevalence of BDD among university students, we aimed to examine the prevalence of this disorder and its associated mental comorbidities among a population of Iranian college students.

2. Objectives

The purpose of this study was to examine the prevalence of BDD among a sample population of college students in Shiraz. The second aim of the present research was to investigate the incidence of mental comorbidities associated with BDD, including OCD, depression, eating disorders, and social anxiety.

3. Methods

This research was a descriptive study in which 750 college students were recruited from different schools of Shiraz University using the cluster sampling method. The participants completed research questionnaires between November 2014 and September 2015. Informed consent was obtained from the students, and the Ethical Research Committee of the Shiraz University approved the research proposal. Statistics indicators such as mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage, and the chi-square test were used to analyze the data. The statistical significance level was considered as P < 0.05.

3.1. The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale

The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOC) is an OCD screening instrument designed to determine the severity of OCD symptoms (13). The scale has 10 items, and each item is rated from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (extreme symptoms). Many studies have reported good reliability and validity for the scale. For example, in one study, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 and a test-retest value of 0.92 were reported (13). Researchers have used this questionnaire in Iran and have reported acceptable reliability and validity with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.93 for the symptom checklist and 0.97 for the severity scale (12).

3.2. The Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire

The Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire (BDDQ) was designed as an instrument for assessing BDD based on the DSM diagnostic criteria (14). The questionnaire contains five items, and responses are rated based on a dichotomous yes or no format. It assesses the degree to which symptoms cause distress or interfere with the individual’s social functioning (14). Several studies have used this questionnaire in Iran and have found it to be a valid and reliable scale (15).

3.3. The Beck Depression Inventory

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) is one of the most popular self-report tools for assessing depression (16). It was designed as an index of depressive symptomatology and severity. The scale has 21 items, and responses are rated on a 0 to 3 scale, with the total score ranging from 0 to 63. Higher scores indicate more severe depression. The BDI has been used in many studies for investigating depressive symptoms, and these surveys have found it to be reliable with a coefficient alpha of 0.86 (16). Numerous studies have used the BDI in Iran, suggesting it as an acceptable tool with satisfactory validity and reliability and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 (17).

3.4. The Moudsley Obsessive Compulsive Inventory

The Moudsley Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (MOCI) (18) is used to assess obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors. The MOCI contains 30 statements with dichotomous (true-false) responses, yielding a maximum score of 30. The tool has four subscales, including checking, washing, slowness, and doubting, with alpha coefficients ranging from 0.70 to 0.80. The reliability and validity of the MOCI have been satisfactory, as shown in a study on an Iranian population with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 (17).

3.5. Social Phobia Inventory

The Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) (19) was developed to assess the symptoms of social phobia, including fear (of people, parties, and social events), avoidance (of talking to strangers), and physiological discomfort (blushing, sweating, and palpitation). The SPIN contains 17 items, and responses are rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Research has shown that the SPIN is a valid and reliable scale (19). The SPIN has been used in Iran, suggesting that the scale has good reliability and validity with the test-retest reliability value of 0.89 (20).

3.6. Eating Attitude Test

The Eating Attitude Test (EAT-26) (21) is a self-report scale developed to assess abnormal eating habits. The EAT-26 consists of 26 items, and respondents rate their agreement with the statements, which are about weight and foods. Participants’ responses are rated from 0 (rare) to 3 (always). A score greater than 20 indicates a possible eating disorder, and individuals who score 20 or more should seek clinical care. Research has shown that this scale has good reliability with an alpha coefficient of 0.79 (22). This measure has been used in Iran, delivering acceptable reliability and validity with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 (23).

4. Results

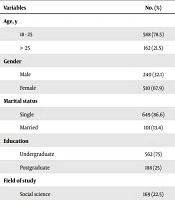

The majority of the participants were single (86.6%) and undergraduate (75%). In terms of age, most of the participants were aged between 18 and 25 years (78.5%) with a mean age of 21.52 (SD = 2.12) years. The point prevalence of BDD among college students was 4.5%. The students’ demographic characteristics have been shown in Table 1.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| 18 - 25 | 588 (78.5) |

| > 25 | 162 (21.5) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 240 (32.1) |

| Female | 510 (67.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 649 (86.6) |

| Married | 101 (13.4) |

| Education | |

| Undergraduate | 562 (75) |

| Postgraduate | 188 (25) |

| Field of study | |

| Social science | 169 (22.5) |

| Engineering | 247 (32.9) |

| Art | 56 (7.5) |

| Science | 117 (15.7) |

| Education | 161 (21.5) |

Of the participants, about 77% were dissatisfied with some parts of their bodies. The overall rates of dissatisfaction with body appearance were 73.3% and 79.4% for male and female students, respectively. About 77% of the students complained of at least one bodily defect. The most common preoccupations were the defects of the skin (21.5%), hair (14.2%), nose (13.6%), weight (7.4%), and stomach (7.2%). The data of body dissatisfaction have been presented in Table 2.

| Body Appearance | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Skin | 161 (21.5) |

| Hair | 106 (14.2) |

| Nose | 102 (13.6) |

| Weight | 56 (7.4) |

| Stomach | 54 (7.2) |

| Height | 43 (5.8) |

| Teeth | 36 (4.8) |

| Breast | 23 (3.1) |

| Other parts | 169 (22.4) |

In terms of gender distribution of symptoms, 3.9% of males and 4.6% of females had BDD symptoms; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P < 0.21). In terms of age, younger students showed more prevalence of BBD symptoms (14%, P < 0.10). In addition, among the students with BDD, 18% had a history of cosmetic surgery. The prevalence of BDD was higher in the individuals who were dissatisfied with their previous cosmetic surgery (33.3%) compared with those who were happy with the surgery (10.9%). The most common concerns about body parts among men were related to the hair (17.9%), skin (15.7%), and nose (9.5%). On the other hand, the most common concerns in women were related to the skin (23.8%), hair (12.8%), and nose (11.1%), respectively.

In terms of checking behaviors, checking in front of a mirror (25.6%), comparing oneself with others (14.8%), and reassuring seeking (18.4%) were the most common behaviors. The description of behavioral obsessions has been presented in Table 3. In terms of associated mental comorbidities, OCD (25.8%), eating disorders (18.3%), depression (20.2%), and social anxiety (23.1%) were the most common conditions.

| Behavioral Obsession | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Checking in front of a mirror | 188 (25.6) |

| Reassuring | 138 (18.4) |

| Seeking treatment | 118 (15.7) |

| Comparing appearance | 111 (15.8) |

| Hiding defects | 69 (9.1) |

| Checking skin | 58 (7.7) |

| Excessive grooming | 36 (4.7) |

| Excessive exercise | 18 (2.4) |

| Excessive cleaning | 15 (2) |

5. Discussion

The results of this study showed that about 77% of the participants were dissatisfied with at least one part of their body. This finding was consistent with other surveys indicating a high prevalence of body dissatisfaction among the general population. For example, in one study, about 72% of college students declared their dissatisfaction with their bodies (24). In terms of the gender distribution of BDD, the findings of this research were nearly similar to those of other epidemiologic studies reporting a higher prevalence of BDD among women than men (1). Furthermore, the findings of the present survey were similar to other studies in Iran, reporting a relatively high prevalence of BDD, particularly among the individuals visiting cosmetic clinics (9, 25). In terms of dissatisfaction with body parts, the results of this research were also consistent with the observations of previous studies. For example, one study reported that young people were more obsessed with their faces, particularly the nose and hair (26). According to a study, body image dissatisfaction is increasing in Iran (27). Indeed, the incidence of BDD in Iran was reported to be higher than other countries such as China and the US (2). Most studies in Iran have reported a high incidence of BDD among young individuals (10). A possible explanation for this appears to be demographic differences among recruited populations. In this regard, our studied population included university students that are younger than the general population. In terms of associated comorbidities, the present survey was in agreement with previous research reporting a high rate of association of BDD with OCD, anxiety, and depression (28). Indeed, because of this high rate of comorbidities and according to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, BDD is categorized under obsessive-compulsive disorders. In terms of depression, individuals with bodily concerns suffer from the symptoms of depression and may even think of suicide (29). Regarding the coincidence of BDD with social anxiety, this study showed that about 25% of individuals with BDD also had social anxiety. Indeed, the individuals who were dissatisfied with their appearance tried to avoid social situations and often had concerns about being negatively judged. Previous studies have found similar results on the association of social anxiety with BDD (30).

This study had several limitations, such as using a questionnaire for assessing BDD and other mental disorders. For future studies, clinical or structured interviews based on the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria should be considered for the diagnosis of these disorders. Furthermore, because there were several questionnaires, it was difficult for the participants to complete the scales.

This study highlighted that the majority of the assessed college students were dissatisfied with at least some parts of their bodies. About 4.5% of the college students had experienced BDD. Overall, this study demonstrated a relatively high prevalence of BDD among college students. This research also indicated a relatively high prevalence of BDD-associated comorbidities such as OCD, eating disorders, depression, and social anxiety. It is important for mental health professionals to be aware of BDD symptoms and provide appropriate therapeutic interventions for those presenting with this condition.