1. Background

One of the issues that affects couples' relationships is the matter of veteran status and the aftermath of war (1). Despite the numerous difficulties they face in life, war veterans must continue their social lives. Disability is associated with slowness in the movement of the arms and legs, loss of sensation in body parts, insufficient tolerance for stress, and sexual dysfunction. These changes can affect their marital relationship, employment status, and social roles. Veteran status is a situation that affects the entire family and has detrimental effects on the marital relationship (2). The veteran's relationship with parents, spouse, and other family members is also an essential part of their lives. Changes in physical appearance, sexual dysfunction, the presence of anxiety, grief, guilt, low self-esteem, and self-efficacy in veterans are associated with numerous consequences for families and affect the emotional climate and mental health of family members (3). Research findings in this area indicate that most veterans, even years after the initial trauma, still struggle with various psychological disorders (4), which also affects the sexual relationship and marital intimacy of couples.

One of the issues frequently reported by dissatisfied couples is the failure to establish effective and healthy communication (5). If couples are unable to express their needs effectively, they are unable to find useful and efficient solutions, and ultimately, the relationship progresses towards stress, frustration, failure, anger, and disillusionment (6). With increasing frustration and intensifying tensions, the source of conflicts may be attributed to the spouse, which can lead to covert relational aggression (CRA), increased marital burnout, and the erosion of love and affection (7).

Violence and aggression are detrimental factors affecting couple interactions. Research indicates that at least one in three couples experiences some form of aggression, including both overt (e.g., physical or verbal) and covert (e.g., emotional or relational) aggression (8). While overt violence negatively impacts communication, CRA represents a more subtle form of aggression aimed at harming a partner through targeted influence and damaging their social standing and sense of belonging (9). Lascorz et al. (10) found minimal gender differences in the prevalence of CRA, which comprises two key components: Social undermining and emotional withdrawal. Social undermining involves spreading rumors and negative gossip about the partner, while emotional withdrawal includes withholding affection and attention, often as a means of control. Behaviors such as ignoring the partner, neglecting their needs, withdrawing from sexual intimacy, and employing the silent treatment are indicative of emotional withdrawal. Converging evidence suggests a link between diminished marital quality and CRA (11).

Another key variable in the context of family structure and couple relationships is family cohesion. Family cohesion refers to the way a family organizes roles and responsibilities, which adapt to various situations and circumstances, requiring a high degree of adaptability and coordination (12). Several theorists, including Murray Bowen, have contributed to the study of family systems, emphasizing the importance of family cohesion and the family's emotional system (13). Family cohesion fosters a sense of connectedness and support. Individuals raised in cohesive families experience a supportive environment characterized by understanding, warmth, affection, and commitment to the needs of other family members. Essentially, family cohesion reflects the roles and responsibilities of family members and the family's capacity to adapt to evolving needs and circumstances (14).

Marital intimacy and satisfaction are enhanced through healthy and effective communication. Maintaining social relationships, particularly marriage, requires strong marital skills to prevent maladaptive communication patterns and relational aggression within the couple dynamic (6). Several therapeutic approaches focus on marital empathy to address these challenges, one of which is Imago Relationship Therapy (IRT). This approach posits that mate selection is based on an idealized mental image of one's parents during childhood, and compatibility with a partner is contingent on this initial image. The ultimate goal of IRT is to harmonize the conscious and unconscious mind (15). The IRT is a process that trains couples to become aware of the unconscious aspects of their relationship and identify the source of recurring conflicts. By providing deeper insight, this approach equips couples with practical skills. Various studies have confirmed the effectiveness of IRT in various aspects of couple relationships, such as communication patterns and marital adjustment (16). Numerous research findings have demonstrated the effectiveness of IRT on marital burnout, resilience, empathic perspective-taking, and forgiveness in couples (17-19).

2. Objectives

Given that a fundamental factor contributing to rising divorce rates and marital discord is the absence of effective communication skills within marriage, providing therapeutic interventions in this area is particularly crucial for vulnerable groups such as veteran couples. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of IRT on CRA and family cohesion in veteran couples.

3. Methods

This study utilized a quasi-experimental design with a pre-test-post-test-follow-up control group to examine the effects of the intervention. Participants were recruited via convenience sampling from veteran counseling and rehabilitation centers in Ahvaz during the fall of 2023, comprising all veteran couples seeking services. A total of 32 couples were included (experimental group: N = 16; control group: N = 16), based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A G*Power analysis confirmed this sample size was sufficient to detect a medium effect size (f = 0.25) for a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with 80% power and an alpha of 0.05, assuming a 0.5 correlation among repeated measures. Inclusion criteria mandated a minimum high school education, absence of diagnosed psychiatric disorders, a veteran spouse, and willingness to participate. Exclusion criteria included psychiatric disorders, concurrent counseling, or missing more than two intervention sessions. Baseline characteristics, such as PTSD severity and marital duration, were balanced across groups, though convenience sampling may still introduce selection bias. Notably, there was no attrition, and complete data were collected from all 32 participants at all assessment points, negating the need for missing data handling.

3.1. Instruments

3.1.1. The Couples Relational Aggression and Victimization Scale

The Couples Relational Aggression and Victimization Scale (CRAViS) was employed to measure covert aggression within couples. This instrument comprises two subscales: Emotional withdrawal (items 1 - 6) and social image destruction (items 7 - 12). Responses are recorded on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very low) to 7 (very high), yielding potential scores from 12 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater levels of covert aggression (20). The Persian adaptation of the CRAViS has also demonstrated acceptable reliability, with a reported Cronbach's alpha of 0.85 (21). In the present study, the CRAViS exhibited excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.90.

3.1.2. The Family Cohesion Scale

The Family Cohesion Scale (FCS), developed by Samani based on relevant literature and Olson’s circumplex model, comprises 28 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Items 1, 2, 7, 13, 14, 15, 16, 23, 25, and 26 are reverse-scored. Potential scores range from 28 to 140. Amani and Babaey Gharmkhani (22) reported a Cronbach's alpha of 0.79 for the FCS. In this study, the FCS demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.81.

3.2. Procedure

Following ethical clearance from the university's research department, data collection commenced at a counseling and rehabilitation center in Ahvaz. After rapport building and ensuring confidentiality, participants completed baseline questionnaires. The experimental group participated in ten 90-minute IRT sessions, conducted in a group format with four couples to facilitate interactive exercises. A doctoral psychology student, trained in IRT and supervised by a licensed faculty advisor specializing in couples therapy, led these sessions. The facilitator adhered to a structured IRT protocol based on Hendrix (23), incorporating techniques such as mirroring, validation, and empathy-building (Table 1). Therapist adherence was ensured through a detailed IRT manual and review of session recordings by the supervisor. Participants were encouraged to engage through role-playing, discussions, and homework. Acknowledged limitations include the absence of blinding for both participants and the therapist, potentially introducing performance bias. The control group was waitlisted without intervention. Post-test assessments were administered immediately post-intervention, with a follow-up at 45 days.

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Establishing rapport and initial assessment; introductions; Outlining session guidelines (including confidentiality, respect, active listening, etc.); Fostering motivation; Identifying the couple's current presenting problem; Establishing couple goals for therapy; Focusing on the history of marital difficulties; Administering the pre-test |

| 2 | Planning for future relationship dynamics; Assessing the potential for relationship growth; Developing personal relationship rules; Identifying desired qualities and aspirations within the relationship; Exploring the partner's belief system; Comparing and identifying commonalities; Creating a shared belief statement using present tense phrasing |

| 3 | Enhancing self-awareness; Reviewing past experiences; Exploring childhood frustrations and coping mechanisms; Cultivating positive mental imagery, such as positive and joyful memories; Documenting positive and negative parental traits and their impact on the individual; Identifying unmet childhood needs and associated negative emotions |

| 4 | Understanding the partner; Articulating the partner's positive and negative traits; Comparing the partner's traits with one's own internal image; Examining the reciprocal influences of one's internal image and the partner's traits |

| 5 | Identifying each other's emotional wounds; Understanding the partner's needs and challenges; Sending clear and effective messages; Practicing conscious dialogue; Emphasizing mirroring, validation, and empathy |

| 6 | Establishing mutual commitment and reassurance of togetherness; Enhancing intimacy; Fulfilling needs; Identifying couple conflicts; Addressing maladaptive coping mechanisms such as overworking, Overeating, and excessive time spent with children as avoidance strategies |

| 7 | Renewing romantic memories and improving the relationship; Increasing intimacy and healing emotional wounds; Establishing a positive interaction cycle; Reviewing positive past behaviors and memories; Identifying unmet needs and desires |

| 8 | Enhancing feelings of security and connection; Fostering emotional bonding; Managing anger constructively; Exploring unresolved past issues; Articulating needs hidden behind despair and disappointment; Expressing requests in a positive manner |

| 9 | Cathartically releasing anger within a constructive environment; Healing past wounds; Addressing various aspects of the disowned self, false self, lost self, and true self; Communicating one's feelings to the partner |

| 10 | Recovering the lost self; Accepting the false self and disowned self; Implementing positive and mature changes; Summarizing and concluding the sessions; Administering the post-test |

3.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using both descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were calculated. Inferential analyses comprised repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc tests. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 27. The significance level was set at P = 0.05. Prior to ANOVA, data normality was confirmed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and homogeneity of variances was assessed via Levene’s test. Mauchly’s test indicated a sphericity violation, addressed using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction. The Box’s M test confirmed homogeneity of covariance matrices across groups (P > 0.05), supporting the robustness of the ANOVA results.

4. Results

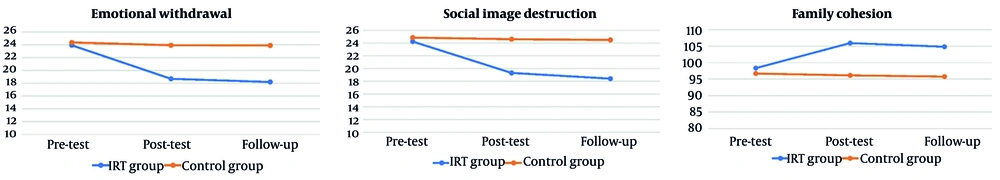

The IRT and control groups each consisted of eight male and eight female participants (i.e., n = 16 per group). Baseline characteristics, such as PTSD severity (assessed via self-report measures) and marital duration (mean of 12.4 years for IRT group, 12.8 years for control group), were balanced between groups (P > 0.05 for all comparisons), minimizing concerns about group differences at baseline. Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for CRA and family cohesion for both the IRT and control groups at pre-test, post-test, and follow-up.

| Variables | IRT Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional withdrawal | ||

| Pre-test | 23.93 ± 3.53 | 24.37 ± 2.58 |

| Post-test | 18.68 ± 3.36 | 23.93 ± 2.74 |

| Follow-up | 18.18 ± 3.20 | 23.91 ± 2.78 |

| Social image destruction | ||

| Pre-test | 24.25 ± 3.19 | 24.87 ± 2.98 |

| Post-test | 19.31 ± 4.14 | 24.62 ± 3.20 |

| Follow-up | 18.41 ± 4.20 | 24.50 ± 3.11 |

| Family cohesion | ||

| Pre-test | 98.31 ± 8.95 | 96.68 ± 7.24 |

| Post-test | 105.93 ± 10.21 | 96.12 ± 7.20 |

| Follow-up | 104.82 ± 10.15 | 95.75 ± 7.46 |

Abbreviation: IRT, Imago Relationship Therapy.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Data are shown in Table 2. Means and standard deviations for CRA and family cohesion in the IRT and control groups at pre-test, post-test, and follow-up.

Prior to data analysis, the assumptions of repeated measures ANOVA were assessed. Data normality was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and results confirmed that the normality assumption was met. Levene's test was conducted to examine the homogeneity of variances for the dependent variables across the experimental and control groups. Mauchly's test of sphericity was significant, indicating a violation of the sphericity assumption; therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. The Box’s M test confirmed homogeneity of covariance matrices across groups (P > 0.05), ensuring the validity of the ANOVA results.

Repeated measures ANOVA revealed statistically significant changes in the dependent variables across the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up assessments (P < 0.001). A significant interaction effect of group by time was observed for both subscales of CRA (emotional withdrawal and social image destruction) and for family cohesion (P < 0.001). Significant between-group differences were also found for all three variables, favoring the IRT group over the control group (P < 0.05, Table 3). The large effect sizes (η2 ranging from 0.78 to 0.89) indicate strong treatment effects.

| Variables | SS | df | MS | F | P | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional withdrawal | ||||||

| Time | 193.56 | 1.26 | 153.46 | 243.22 | 0.001 | 0.89 |

| Time × group | 133.89 | 1.26 | 106.15 | 168.24 | 0.001 | 0.78 |

| Group | 341.26 | 1 | 341.26 | 12.56 | 0.001 | 0.30 |

| Social image destruction | ||||||

| Time | 147.06 | 1.33 | 110.09 | 177.95 | 0.001 | 0.85 |

| Time × group | 114.14 | 1.33 | 85.45 | 138.12 | 0.001 | 0.82 |

| Group | 330.04 | 1 | 330.04 | 9.12 | 0.005 | 0.23 |

| Family cohesion | ||||||

| Time | 228.81 | 1.25 | 181.89 | 112.37 | 0.001 | 0.78 |

| Time × group | 339.43 | 1.25 | 269.83 | 166.70 | 0.001 | 0.84 |

| Group | 1155.09 | 1 | 1155.09 | 5.24 | 0.021 | 0.15 |

Abbreviations: SS, Sum of Squares; MS: Mean Square.

Table 4 presents the results of Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons examining differences across the three assessment points (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up) for the CRA subscales (emotional withdrawal and social image destruction) and family cohesion in both the IRT and control groups. Within the IRT group, significant improvements were observed from the pre-test to both the post-test and follow-up for both CRA subscales and family cohesion (P < 0.001). In contrast, no significant changes were found at any assessment point within the control group. There were no significant differences between the post-test and follow-up assessments for either group (Figure 1).

| Variables | Phase A | Phase B | IRT Group | Control Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Difference (A - B) | P | Mean Difference (A - B) | P | |||

| Emotional withdrawal | Post-test | Pre-test | 5.25 | 0.001 | 0.43 | 0.232 |

| Follow-up | Pre-test | 5.75 | 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.131 | |

| Follow-up | Post-test | 0.50 | 0.180 | 0.12 | 0.864 | |

| Social image destruction | Post-test | Pre-test | 4.93 | 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.843 |

| Follow-up | Pre-test | 4.93 | 0.001 | 0.37 | 0.462 | |

| Follow-up | Post-test | 1.09 | 0.999 | 0.12 | 0.999 | |

| Family cohesion | Post-test | Pre-test | 7.62 | 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.613 |

| Follow-up | Pre-test | 6.81 | 0.001 | 0.93 | 0.100 | |

| Follow-up | Post-test | 0.81 | 0.152 | 0.37 | 0.232 | |

Abbreviation: IRT, Imago Relationship Therapy.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the effectiveness of IRT in addressing CRA and fostering family cohesion among veteran couples. The findings indicate that IRT significantly improved both CRA and family cohesion, with these positive effects sustained at follow-up. Specifically, IRT led to a reduction in both emotional withdrawal and social image destruction, consistent with existing research (17, 24). The mechanisms underlying IRT's effectiveness can be attributed to its core techniques, including mirroring, validation, and empathy-building exercises (15). Mirroring, which involves active listening and repeating a partner's statements, promotes mutual understanding and mitigates emotional withdrawal by encouraging open communication (7). Validation, by acknowledging a partner's feelings, helps counter social image destruction, fostering a sense of acceptance (9, 24). These techniques align with previous studies demonstrating IRT's efficacy in enhancing communication and reducing relational conflict (17, 24).

Furthermore, IRT utilizes mental imagery to guide couples in exploring childhood memories, facilitating insight into early experiences and processing emotional wounds. This therapeutic process addresses critical relational issues such as power struggles, anger management, sexuality, and forgiveness. Hendrix's communication strategies, encompassing empathy, verbal intimacy, mutual validation, and mirroring, further contribute to these positive outcomes (15). The observed large effect sizes, notably exceeding typical benchmarks in couples therapy literature (24, 25), suggest a robust impact on CRA and family cohesion. However, the relatively small sample size warrants cautious interpretation of these promising findings.

The CRA is a form of aggression within intimate relationships, characterized by manipulative behaviors designed to harm a partner's social standing and sense of acceptance (8). These behaviors damage a partner's relationships, undermine their social belonging, and disrupt their friendships, ultimately aiming to inflict damage on their self-esteem and character. While men in marital relationships tend to use physical aggression, women are more inclined to engage in CRA. Social undermining within CRA is linked to feelings of insecurity and betrayal. Emotional withdrawal, a component of CRA, involves one partner deliberately withholding attention and affection to control the relationship (7). The observed mean reductions in CRA scores (approximately 5 points on both emotional withdrawal and social image destruction subscales) suggest clinically meaningful improvements. For instance, a 5-point decrease on the CRAViS emotional withdrawal subscale likely indicates a reduction in behaviors such as the silent treatment or withholding affection. Similarly, a comparable reduction on the social image destruction subscale may reflect less frequent negative gossip or public criticism of the partner, thereby enhancing relational trust and intimacy (9).

In IRT, therapists guide couples to focus on their interpersonal dynamics, identify recurring conflicts, and understand how these patterns impact their relationship. The therapy facilitates the identification of their own and their partner's emotional needs, fostering a deeper understanding of each other's feelings and needs. It also aims to enhance interpersonal and empathic skills, enabling couples to communicate more effectively and express their feelings, desires, and concerns constructively, thereby facilitating conflict resolution (24). Furthermore, IRT encourages couples to revisit their relationship history and examine past experiences to understand their influence on current relational dynamics. Consequently, this approach can mitigate components of CRA within the couple.

The results also indicated that IRT led to improved family cohesion among the couples. This finding aligns with the results of previous studies (18, 25). The IRT is a therapeutic process that facilitates couples' awareness of unconscious aspects of their relationship and the identification of recurring conflict patterns. By providing deeper insight, this approach equips couples with practical skills. The 7 - 8 point increase in FCS scores suggests enhanced family cohesion, but the specific FCS items driving these changes (e.g., role adaptability, emotional support) were not analyzed at the item level in this study, limiting granularity in understanding which aspects of cohesion improved most. Future research should examine item-level FCS data to identify whether improvements were driven by enhanced role coordination, emotional bonding, or other cohesion facets (14, 22).

Family cohesion refers to the way a family organizes roles and responsibilities. These roles and responsibilities adapt to various situations and circumstances, requiring a high degree of adaptability and coordination (22), which can themselves be a source of conflict. The IRT assists couples in identifying the root causes of these conflicts and actively working towards their reduction (26). In explaining the findings, it can be argued that within IRT, therapists facilitate couples' understanding of each other's emotions and needs through specific techniques, encouraging the cultivation of respect and empathy within their relationship. Consequently, tensions and misunderstandings are diminished. Furthermore, IRT helps each partner understand how their behavioral patterns and emotions influence their interactions and how they can implement positive changes in these patterns. Additionally, it provides training in conflict management and problem-solving, which can lead to healthier and more stable family relationships (25). Therefore, this approach can enhance family cohesion.

This study's quasi-experimental design presents several limitations. Unmeasured confounding variables, including veterans' trauma exposure, couples' demographics (age, presence of children), reasons for counseling, and educational variations, were not controlled. Crucially, veteran-specific factors like combat exposure and disability severity were also not assessed, potentially influencing outcomes related to CRA and family cohesion. These unmeasured factors may have led to sample inhomogeneity, thus limiting the generalizability and validity of the findings. Despite balanced baseline characteristics, convenience sampling and the absence of blinding for participants and therapists likely introduced selection and performance biases. The small sample size further restricts the findings' representativeness. Future research should mitigate these limitations by controlling for confounders, including veteran-specific factors, employing larger and more diverse samples, implementing blinding, and explicitly reporting statistical assumptions.

5.1. Conclusions

This study provides strong evidence for the efficacy of IRT in addressing relational challenges among veteran couples in Ahvaz. Significant improvements were observed in both CRA reduction and family cohesion in the experimental group, persisting through follow-up. These findings suggest IRT fosters lasting positive changes in communication and relational dynamics, significantly contributing to the literature on couple therapy for veterans. However, generalizing these results to diverse veteran populations, particularly Western cohorts, requires caution due to potential cultural, military, and social contextual differences. Future research should investigate the mechanisms underlying IRT's effectiveness and explore its applicability across varied veteran demographics and longer follow-up periods.