1. Background

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and some chronic diseases are preventable (1) and can be treated by changes in lifestyle behaviors such as eating habits, sleep, physical activity (PA), weight control, smoking, and alcohol consumption, etc. (2). Studies have shown that high blood pressure (BP) is an important risk factor for heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, heart valve diseases, aortic syndromes, and dementia, in addition to coronary heart disease and stroke (3). High BP leads to left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction, so BP control should be implemented to prevent the development of overt heart failure (4). Increasing the level of uric acid (UA) can also lead to kidney damage. The UA is a compound of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen elements with the chemical formula C5H4N4O3. It seems that an active lifestyle can be effective in controlling UA levels (5). Evidence shows that 150 to 300 minutes of moderate PA per week has significant benefits in maintaining the health of the human body (6). Youth physical inactivity contributes to key global health problems, and efforts to improve youth PA are necessary (7). Studies have shown that PA is an important proposed method for controlling and treating BP (8).

Consumption of foods containing flavonoids has reduced the mortality rate due to CVD, and green tea can be mentioned among the foods that have more flavonoids (9). Green tea (Camellia sinensis) is widely known for its anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory properties. Among the biologically active compounds in C. sinensis, the main antioxidant agents are catechins, and the group of green tea catechin derivatives includes epicatechin, catechin, epicatechin gallate, and catechin gallate (10). On the other hand, walking as a simple PA was significantly associated with lower levels of UA and the prevalence of hyperuricemia (11, 12). Also, regarding supplements and their effects on blood UA levels, research shows that green tea catechins can increase the excretion of UA (13). Dietary approaches to stop hypertension and nutritional agents such as beverages with antioxidant activity (green tea), and flavonoids in several dietary supplements have shown the ability to lower BP and thus prevent the risk of cardiovascular disease. Therefore, green tea can be considered an important source of antioxidants, which has a high level of phenols and antioxidant capacity. In particular, its polyphenolic flavonoids can prevent the occurrence and progression of atherosclerosis as well as CVD (14).

2. Objectives

In this research, we investigated the simultaneous effect of walking and taking green tea supplements on reducing BP and blood UA levels in inactive male students. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the effect of 8 weeks of walking and drinking green tea on the BP and UA levels of inactive male students.

3. Methods

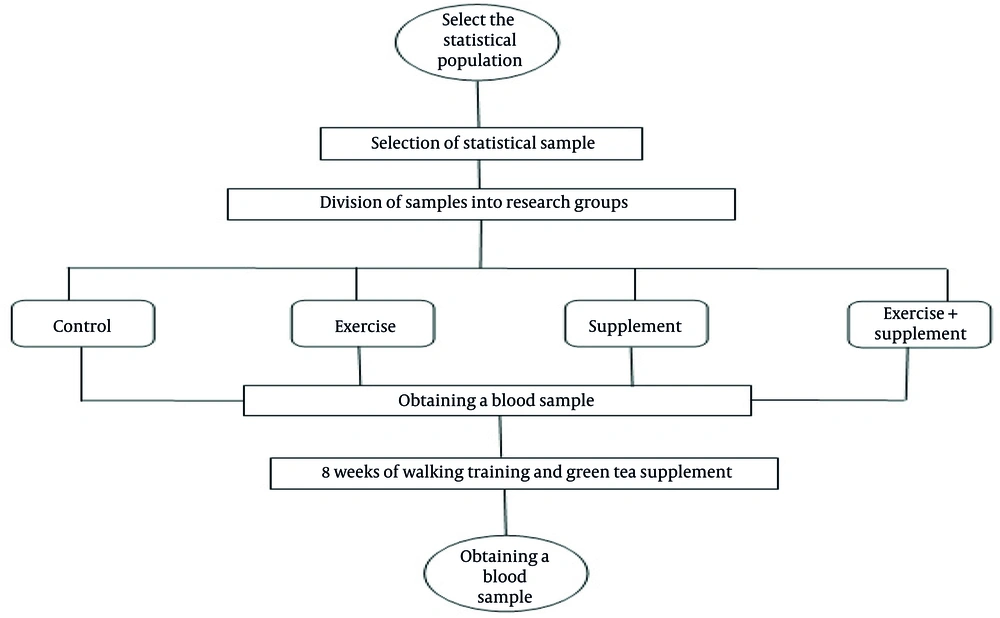

In this research, we investigated the simultaneous effect of walking and green tea supplementation on the BP and UA levels of inactive male students. Sixty inactive male students from Persian Gulf University voluntarily participated in this study and were then randomly divided into four groups: Control, supplement, exercise, and exercise + supplement. The inclusion criteria for this study included being a dormitory resident, being inactive, and not having BP above 14, while the exclusion criteria included having any disease related to BP and engaging in regular PA. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment in the study. Participants were fully informed about the study objectives, procedures, potential risks, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. All personal data were anonymized using numerical codes, and identifying information (e.g., names, student IDs) was removed from data files to ensure confidentiality.

Subjects in the exercise and exercise + supplement groups practiced walking three sessions a week for 30 minutes at moderate intensity (110 - 120 steps per minute) for 8 weeks. Exploratory values were determined as 110 steps per minute to 120 steps per minute, with a PPV of 70.7 (15). The subjects in the supplement and exercise + supplement groups took their supplement three times a week for 8 weeks. After the main meal, they consumed a tablet containing 500 mg of leaf and standardized green tea extract (20 mg cumin seeds and 20 mg dill seeds) (16). Before and after the 8-week intervention, BP and biochemical parameters were evaluated (Figure 1).

The supplement used in this study was Green Tidine (Dineh Pharmaceutical Co., Iran). Each tablet contained 500 mg of standardized green tea leaf powder, which includes 50 mg of total polyphenols, particularly catechins such as EGCG, ECG, EGC, and gallocatechin. Additionally, each tablet contained 20 mg of cumin seed and 20 mg of dill seed powder. The supplement was standardized using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to ensure consistent polyphenol content across batches. Although no independent analysis was conducted by the research team, the product is commercially certified for batch-to-batch consistency in its active ingredients, as stated by the manufacturer. This study is approved under the ethical approval code of the Ethics Committee of Sport Sciences Research Institute SSRI.REC-2311-2521.

3.1. The Method of Measuring Variables

Blood sampling was taken 24 hours before and after the training period, with BP measured in a sitting position after 5 minutes of rest. All measurements were conducted in a sitting position on the left wrist at the level of the heart using an Amren digital sphygmomanometer, model M2. Additionally, 5 cc of blood was drawn from the brachial vein of each subject, and it was immediately used to separate the serum using a centrifuge at a speed of 3500 rpm for 10 minutes with a centrifuge 5430 Eppendorf model made in Germany (15). Serum levels of UA were measured by the calorimetric method using dL/mg Biorex UA kits and Biorex1 biochemistry normal control (Asalb model, produced by Farasamad Company, Iran).

3.2. Statistical Method

Data were analyzed using SPSS (Version 25). A two-way ANOVA was used to compare the groups, and a dependent t-test was used to compare the pre- and post-test variables. An alpha level of less than P < 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the subjects in the research groups. Table 2 provides the description of the mean and standard deviation of the variables in the study groups.

| Groups | Age | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 21.09 ± 0.28 | 178.36 ± 1.92 | 81.09 ± 4.60 |

| Exercise + supplement | 19.86 ± 0.41 | 177.06 ± 1.29 | 69.53 ± 3.01 |

| Supplement | 21.35 ± 0.63 | 179.64 ± 1.81 | 78.78 ± 3.85 |

| Exercise | 21.14 ± 0.46 | 178.42 ± 1.49 | 79.07 ± 3.41 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

| Variables | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Exercise + Supplement | Supplement | Exercise | |

| Pre-test | ||||

| BP (mmhg) | 130.27 ± 14.52 | 135.79 ± 17.91 | 124.77 ± 14.49 | 141.74 ± 17.69 |

| UA (mg/dL) | 5.29 ± 1.37 | 4.74 ± 0.94 | 5.48 ± 1.94 | 5.33 ± 1.21 |

| Post-test | ||||

| BP (mmhg) | 133.76 ± 14.47 | 126.09 ± 7.52 | 126.92 ± 7.09 | 127.63 ± 11.57 |

| UA (mg/dL) | 5.28 ± 1.106 | 4.86 ± 0.90 | 5.60 ± 2.43 | 5.22 ± 1.02 |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; UA, uric acid.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

The results of the two-way ANOVA indicated that walking exercise had a significant effect on the BP of the subjects (P = 0.001, F = 208.15). However, the exercise + supplement group (P = 0.449, F = 0.582) and green tea supplement consumption alone did not have a significant interaction effect on the BP of the subjects (P = 0.686, F = 0.165). Changes in UA were not significant in the walking exercise group (P = 0.834, F = 0.044), the green tea supplement group (P = 0.462, F = 0.549), and the green tea supplement + walking exercise group (P = 0.844, F = 0.039).

The results of the Tukey post-hoc test revealed a significant difference in BP between the exercise group and the supplement group (P = 0.018), as well as between the exercise group and the control group (P = 0.011; Table 3). The Tukey post-hoc test results also showed that there was no significant difference in UA levels between the groups (Table 4).

| Groups (I; J) | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | P-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Suppl | |||||

| Exer + suppl | 110.8437 | 50.23823 | 0.121 | -20.0773 | 250.7648 |

| Exercise | 160.2581 a | 50.32438 | 0.018 | 20.1081 | 300.4081 |

| Control | -10.3444 | 50.53389 | 0.995 | -160.0512 | 130.3624 |

| Exer + suppl | |||||

| Suppl | -110.8437 | 50.23823 | 0.121 | -250.7648 | 20.0773 |

| Exercise | 40.4143 | 50.13703 | 0.826 | -90.2378 | 180.0664 |

| Control | -130.1882 | 50.35388 | 0.078 | -270.4166 | 10.0402 |

| Exercise | |||||

| Suppl | -160.2581 a | 50.32438 | 0.018 | -300.4081 | -20.1081 |

| Exer + suppl | -40.4143 | 50.13703 | 0.826 | -180.0664 | 90.2378 |

| Control | -170.6025 a | 50.43820 | 0.011 | -320.0550 | -30.1500 |

| Control | |||||

| Suppl | 10.3444 | 50.53389 | 0.995 | -130.3624 | 160.0512 |

| Exer + suppl | 130.1882 | 50.35388 | 0.078 | -10.0402 | 270.4166 |

| Exercise | 170.6025 a | 50.43820 | 0.011 | 30.1500 | 320.0550 |

a P < 0.05.

| Groups (I; J) | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | P-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Suppl | |||||

| Exer + suppl | 0.7410 | 0.56130 | 0.555 | -.7507 | 2.2327 |

| Exercise | 0.3791 | 0.57053 | 0.910 | -1.1371 | 1.8954 |

| Control | 0.3244 | 0.59298 | 0.947 | -1.2515 | 1.9003 |

| Exer + suppl | |||||

| Suppl | -0.7410 | 0.56130 | 0.555 | -2.2327 | 0.7507 |

| Exercise | -0.3619 | 0.55046 | 0.912 | -1.8248 | 1.1010 |

| Control | -0.4167 | 0.57369 | 0.886 | -1.9413 | 1.1080 |

| Exercise | |||||

| Suppl | -0.3791 | 0.57053 | 0.910 | -1.8954 | 1.1371 |

| Exer + suppl | 0.3619 | 0.55046 | 0.912 | -1.1010 | 1.8248 |

| Control | -0.0548 | 0.58273 | 1.000 | -1.6034 | 1.4939 |

| Control | |||||

| Suppl | -0.3244 | 0.59298 | 0.947 | -1.9003 | 1.2515 |

| Exer + suppl | 0.4167 | 0.57369 | 0.886 | -1.1080 | 1.9413 |

| Exercise | 0.0548 | 0.58273 | 1.000 | -1.4939 | 1.6034 |

The results showed that, compared to the control group, BP in the exercise + supplement groups did not change significantly (P = 0.78), but in the exercise group, BP decreased significantly (P = 0.011). Additionally, the results indicated that the level of serum UA did not change significantly in any of the supplement (P = 0.947), exercise (P = 1.000), and supplement + exercise (P = 0.886) groups. The results of the t-test demonstrated that, compared to the pre-test, supplementation with walking exercise led to a decrease in the subjects' BP (P = 0.041), and walking exercise alone also reduced the subjects' BP (P = 0.001; Table 5).

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Statistically significant (P < 0.05).

The results of the t-test showed that, in comparison to the pre-test, the changes in UA in the blood samples were not significant in any of the research groups (Table 6).

| Groups | Pre-test | Post-test | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.37 ± 5.29 | 1.10 ± 5.28 | 0.979 |

| Exercise | 1.21 ± 5.33 | 1.02 ± 5.22 | 0.585 |

| Supplement | 1.94 ± 5.48 | 2.43 ± 5.60 | 0.723 |

| Exercise + supplement | 0.94 ± 4.74 | 0.90 ± 4.86 | 0.194 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

5. Discussion

The results of this research showed that eight weeks of walking activity and green tea supplementation had a significant effect on reducing BP compared to the pre-test. Additionally, walking exercise alone, both compared to the pre-test and the control group, reduced the BP of the subjects. The study by Asefmehr and Bahranian demonstrated that walking with zinc reduces BP, which was consistent with the results of our study (16). Similarly, the study by Hosseini et al. on middle-aged individuals showed that increased PA leads to a greater decrease in BP (17). Mendelson et al. reported that walking with moderate intensity lowers BP (18). However, in the studies by Mahmoodi et al., titled "Changes in heart structure and BP after a period of simultaneous endurance-resistance training in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) ", a reduction in BP was not observed (19). In the study by Mahdavi-Roshan et al., it was shown that green tea, compared to black tea, caused a significant reduction in BP (20).

Some of the reasons for the discrepancy between some studies and the present study can be attributed to differences in variables such as the intensity and duration of the activity and the muscle groups involved in the activity (19, 21). These changes in BP are intended to cause physiological changes in BP and heart rate during exercise. With the onset of activity, there is an increase in sympathetic stimulation and plasma catecholamines, along with a decrease in parasympathetic activity, leading to changes in BP and heart rate. This increase becomes more or less proportional to the intensity of the activity. Diastolic BP reduction occurs only after low-intensity activity, and this reduction does not occur after high-intensity activity, indicating that the mechanism of diastolic BP reduction post-exercise can be related to the activity method. Therefore, low-intensity exercise may be more beneficial for long-term BP reduction in patients with abnormal BP (22, 23).

However, in the present study, a significant decrease in BP was observed only in the exercise group, suggesting that the additive effect of green tea alone may be minimal or nonsignificant. The use of other doses of green tea and a longer duration of consumption are recommended in future studies to evaluate the effect of green tea on BP. Previous studies have shown that green tea catechins have a protective effect on the heart through multiple mechanisms, including inhibition of oxidation, vascular inflammation, and thrombogenesis (blood clot formation), as well as improving endothelial (inner layer of blood vessels) dysfunction (24, 25).

Polyphenols, particularly catechins found in green tea such as EGCG, have been shown to exert antihypertensive effects through multiple mechanisms. These include improving endothelial function by enhancing nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, reducing oxidative stress via inhibition of NADPH oxidase, and modulating the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), leading to vasodilation and reduced peripheral resistance (10). Furthermore, catechins possess anti-inflammatory properties by downregulating NF-κB activation and cytokine production. Regarding UA metabolism, polyphenols may inhibit xanthine oxidase activity, an enzyme involved in UA synthesis, thereby lowering serum UA levels (26). Although our study did not find significant changes in UA, the potential inhibitory effect on xanthine oxidase may be dose- or duration-dependent and warrants further investigation.

Our results showed that walking activity and the consumption of a green tea supplement, both compared to the control group and the pre-test, caused a slight increase in the level of blood UA, and the supplement group also showed a slight increase in blood UA levels. Haghshenas et al. reported no significant reduction in UA levels in wrestlers following barhang and allopurinol supplementation (26). In another study, there was no decrease in UA following ten weeks of aerobic exercise in untrained girls (27). Rajabi et al.'s study, which involved Wikstrom's fatigue protocol in male volleyball players, also showed no change in UA levels (28). In the studies by Rahimi and Homaei, which examined the protective effect of regular aerobic exercise on kidney damage caused by creatine monohydrate supplements in rats, the results showed a decrease in UA levels, which was not consistent with our findings (29).

While potential mechanisms such as enhanced renal clearance or modulation of cortisol levels may partly explain the BP reduction observed, these interpretations remain speculative in the absence of direct biochemical measurements. A more critical comparison with the findings of Rahimi and Homaei (29) is warranted. In their study, significant reductions in both systolic and diastolic BP were observed following 8 weeks of green tea supplementation in sedentary men, consistent with our findings in the exercise and exercise + supplement groups. However, their intervention lacked an exercise component, which may have limited the synergistic interpretation of results. Furthermore, unlike our study, they reported a significant reduction in UA levels, possibly due to differences in dosage, supplement form (e.g., extract vs. powder), or baseline metabolic profiles of participants. This highlights the importance of contextual factors in interpreting outcomes and suggests that the dose-response relationship and individual variability warrant further study.

We did not find studies related to the effect of green tea supplementation on UA levels, highlighting the necessity of conducting such studies. Reactive oxygen species play an important role in the initiation and propagation of muscle fiber damage after initial mechanical injury through exercise (30). The instability of the cell membrane and the release of intracellular proteins into the extracellular space increase the blood CK level (31). Therefore, increasing the level of UA probably reduces the damage caused by free radicals, especially muscle damage. In the present study, we observed a slight increase in the level of UA (32).

In the study by Yu et al., it was reported that tea intake was negatively associated with renal function impairment and there was no causal association with UA (33). Additionally, Chen et al. reported that tea consumers tended to have higher UA levels than non-tea consumers across all three datasets, and longitudinal associations of UA levels with tea consumption had no statistical significance. The results of sex-stratified analyses were consistent with those of the whole datasets (34). It is also suggested that increased cortisol levels during exercise, which contribute to muscle damage, release endogenous purines from muscle tissue, and that exercise increases serum UA due to decreased renal clearance (35). Overall, the available data suggest that tea drinking may be associated with elevated serum UA. Due to the limited number of studies, further well-designed prospective studies and randomized controlled trials are needed to elaborate on these issues (36).

Research data reported that the lighter the fermentation, the greater the potential for inhibiting the production of UA. Furthermore, analyses of the inhibitory effects of its main biochemical active ingredients showed that the inhibitory effects of polyphenols rich in some tea were significantly stronger than caffeine-rich, highly fermented tea (37). Given the small observed effect size for serum UA and the relatively low sample size (n = 15 per group), the statistical power of this study to detect significant changes in UA was very low (approximately 6%), which can be considered a limitation of our study. This indicates a high risk of type II error, meaning that true differences may have gone undetected. Future studies with larger sample sizes are recommended to ensure adequate statistical power.

Another limitation of the present study is the lack of strict control over participants’ dietary intake and hydration levels during the intervention period. Failure to control for diet and hydration confounders is another limitation that could be addressed in future research. Although participants were advised to maintain their usual eating and drinking habits, variations in nutrient intake, sodium consumption, or fluid balance may have influenced outcomes such as BP or UA levels. Future studies should consider implementing dietary logs or hydration monitoring to reduce potential confounding effects.

5.1. Conclusions

The current results showed that walking and green tea had a positive and significant effect on lowering BP. However, the results also indicated that these methods did not affect the UA level. This means that despite the positive effect of green tea and walking on BP, these two factors in this study could not help reduce the level of UA in the body. In conclusion, although green tea and walking are recommended as effective methods to reduce BP, other methods and interventions are needed to reduce UA levels.