1. Background

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Allo-HSCT) has become a cornerstone therapy for hematological malignancies. Nevertheless, major complications after transplantation — including relapse, acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and infections — are associated with increased mortality and morbidity rates, highlighting their clinical importance (1). The GVHD results from interactions between donor and recipient innate and adaptive immune responses: Donor T-cells react against recipient tissues, such as the liver, skin, and gastrointestinal tract, leading to acute or chronic GVHD (2). Typically, acute GVHD occurs within the first 100 days post-transplantation, while chronic GVHD arises more than 100 days after transplantation. Other subtypes, including new-onset acute GVHD (after 100 days) and overlap syndrome (with features of both acute and chronic GVHD), have also been described (3-5).

There are limitations in diagnostic and prognostic methods for GVHD; the lack of validated laboratory tests complicates prediction of outcomes after Allo-HSCT. Biomarkers, defined as measurable characteristics that have adequate sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value, can be evaluated to reveal biological, pathogenic, and pharmacological processes (4). Biomarkers have the potential to estimate acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) risk, prognosis, and treatment responsiveness. Therefore, identifying noninvasive peripheral blood biomarkers could be valuable for improving aGVHD diagnosis and determining personalized treatment plans for patients at higher risk for aGVHD and mortality (3, 6, 7).

Previous studies have highlighted that laboratory biomarkers — such as C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, and albumin — measured prior to Allo-HSCT in patients with hematological malignancies can improve prediction of post-transplant outcomes, including overall survival (OS), GVHD incidence, relapse, treatment-related mortality (TRM), and non-relapse mortality (NRM) (8, 9). The CRP is an acute-phase protein and a widely used biomarker of systemic inflammation, primarily produced by hepatocytes. Inflammation represents the body's defense mechanism against injuries, infections, autoimmune disorders, and chronic diseases. Several studies have suggested that high pre-transplant serum CRP levels are associated with early complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) (2, 10, 11). Recent literature emphasizes that pre-transplant inflammatory biomarkers, including CRP, mainly reflect baseline immune activation rather than serving as reliable discriminatory predictors on their own. Their greatest value appears when interpreted within a composite, multi-parameter prognostic context (12, 13).

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the prognostic significance of serum CRP levels before transplantation in patients who underwent Allo-HSCT and to evaluate the association between this biomarker and transplantation outcomes. Additionally, the relationships between certain risk factors and serum CRP levels were assessed.

3. Methods

3.1. Patients

A total of 206 patients who underwent Allo-HSCT were evaluated in this retrospective single-institution study. Data were collected by reviewing clinical records from 2008 to 2018. Patients with hematological disorders — including acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), aplastic anemia (AA), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and other conditions — who received peripheral blood Allo-HSCT were included. Seventy-six patients whose documentation was incomplete or who died before neutrophil and platelet engraftment were excluded. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched related and sibling donors (6/6 HLA matches) were considered fully matched donors. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the local Ethics Committee of the University (IR.SBMU.REC.1398.118), and all participants signed informed consent.

3.2. Stem Cell Mobilization and Harvesting

All donors received granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF, 5 - 10 µg/kg) as a subcutaneous injection for 4 - 5 days. Peripheral hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) were harvested using the Spectra Optia system (Terumo BCT, Lakewood, CO, USA). CD34+ and CD3+ cell counts were determined on day 5 after G-CSF administration by flow cytometry (Attune NxT, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA); cell counting utilized PE-conjugated human anti-CD34 (EXBIO, Czech Republic) and FITC-conjugated human anti-CD3 (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA).

3.3. Transplantation Procedure

All patients received a standard myeloablative conditioning regimen consisting of busulfan (0.8 mg/kg IV every 6 hours for 4 days) followed by cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg IV for 2 days) or fludarabine (30 mg/m2 IV once daily for 3 days). Patients with mismatched donors received antithymocyte globulin (ATG) as part of the conditioning regimen. Reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) included fludarabine (30 mg/m2 IV for 5 days), CCNU (lomustine) (100 mg/m2 orally for 2 days), and melphalan (40 mg/m2 IV for one day). Conditioning regimens were categorized into five groups: Busulfan plus cyclophosphamide (BU+CY), busulfan plus fludarabine (BU+FLU), busulfan plus fludarabine plus ATG (BU+FLU+ATG), RIC (fludarabine plus CCNU plus melphalan), and cyclophosphamide plus ATG for patients with AA and Fanconi anemia (AF).

The GVHD prophylaxis included cyclosporine A (CsA) alone or in combination with methotrexate (MTX). All patients received ciprofloxacin for bacterial prophylaxis, fluconazole or itraconazole for fungal prophylaxis, and acyclovir for herpes simplex virus prophylaxis.

3.4. Biomarker Measurement

Peripheral blood samples were collected in tubes without anticoagulants and analyzed in the hospital laboratory. The CRP levels in serum were measured alongside routine clinical tests using an immunoturbidimetric assay with a CRP latex kit (Bionic, Iran) on a Hitachi 912 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Normal serum CRP levels were defined as 0 - 6 mg/dL. The CRP was measured on the day of admission, during conditioning, and on the stem cell infusion day (day 0). Cytomegalovirus (CMV) PCR monitoring was performed routinely using the CMV quantitative real-time PCR Kit (DynaBio™, Iran).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The primary goal was to determine the optimal cut-off point for serum CRP to predict GVHD (acute and chronic), aGVHD, and OS at three time points: Admission day, the interval from first conditioning to HSCT (FCH), and the interval between admission and HSCT (AH). The "time period between admission and HSCT" is typically longer than "time interval from first conditioning to HSCT", as conditioning usually begins about seven days after admission.

The secondary goal was to investigate the relationship between high CRP (serum CRP greater than the threshold) before transplantation and both aGVHD and OS, as well as associations between pre-transplant risk factors (such as age, diagnosis, CMV status, conditioning and prophylaxis regimens) and high CRP. Predictive values of serum CRP for aGVHD and OS were evaluated using receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analyses. The cut-off value was determined by ROC analysis and the Youden Index (J = sensitivity + specificity - 1) for each time interval. Among the three time intervals, the admission-day threshold of 7 mg/dL demonstrated the highest Youden Index and was selected as the final cut-off to dichotomize patients into high versus low CRP groups in regression analyses.

The ROC-derived area under curve (AUC) values describe the univariable discriminatory ability of CRP as a single classifier. However, discrimination and independent association are distinct; multivariable logistic and Cox regression models were therefore used to assess whether CRP retained prognostic relevance after adjustment for clinical covariates. All effect estimates were recalculated using 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The OS was defined as the time from transplantation to death from any cause or last follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to estimate and compare OS. Univariable and multivariable analyses of time-to-event data were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using the score process plot and Kolmogorov-type supremum test (significance level 0.05). Multivariable analysis used a backward method for variable selection; variables were excluded at significance level 10%. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression was used to predict aGVHD using serum CRP. Descriptive analysis of risk factors was performed for high and low CRP groups.

The logistic regression model for aGVHD adjusted for recipient age, donor type, HLA match status, conditioning regimen intensity, graft source, ATG administration, and CMV serostatus. The Cox model for OS adjusted for age, disease status at transplant, conditioning regimen, graft source, donor type, and ATG use. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R (version 3.0.1). Significance levels for univariable and multivariable logistic regression were 25% and 5%, respectively. For univariable Cox regression, the significance level was set at 25% (14, 15).

4. Results

4.1. Predictive Value of Serum C-reactive Protein Before Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease

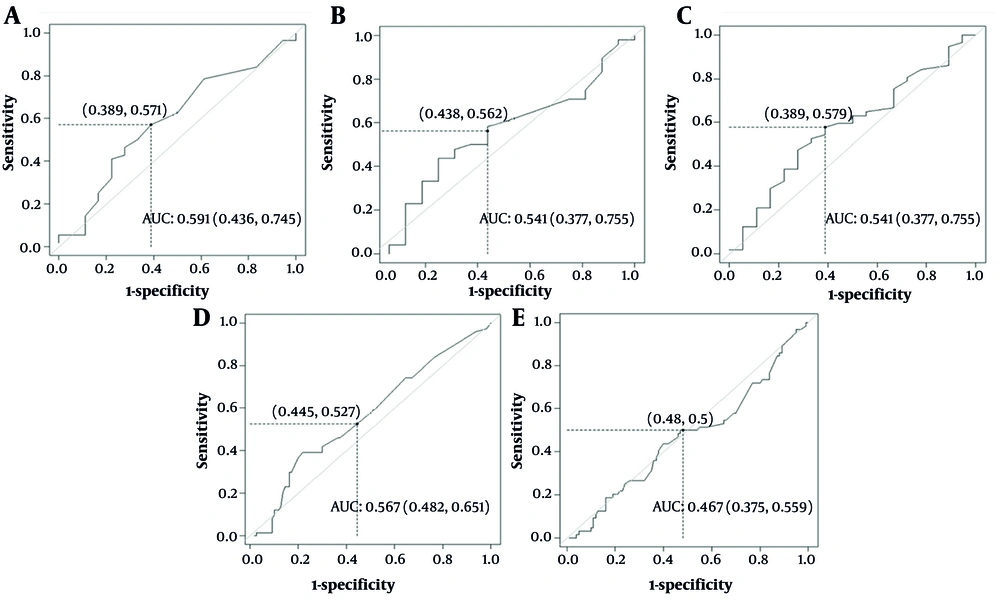

The ROC analyses were performed to assess the value of pre-transplant serum CRP for predicting GVHD and aGVHD. As presented in Table 1, the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity on the admission day for aGVHD were 59.1% (43.6 - 74.5), 57.1%, and 61.1%, respectively, with a cut-off value of 7 mg/dL (Figure 1A). Thus, baseline CRP on admission day can only be used insufficiently to predict aGVHD, as the AUC is close to 60%. Accordingly, a CRP level ≥ 7 mg/dL on admission was selected as the operational cut-off for defining high CRP in further regression analyses.

| Time | Thresholds | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC% (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admit aGVHD | 7 | 57.1 | 61.1 | 59.1 (43.6 - 74.5) |

| FCH aGVHD | 5.8 | 58.3 | 56.2 | 54.1 (37.3 - 70.5) |

| Admit to HSCT aGVHD | 8.15 | 57.9 | 61.1 | 58.1 (42.9 - 73.3) |

| Admit GVHD | 7 | 52.7 | 55.4 | 56.7 (48.2 - 65.1) |

| FCH GVHD | 7.25 | 50 | 53 | 46.7 (37.5 - 55.9) |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; CI, confidence interval; aGVHD, acute graft-versus-host disease; FCH, first conditioning to HSCT; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) assessment of pre-transplant C-reactive protein (CRP) for predicting (acute and chronic) graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD): A, aGVHD for admission day; B, aGVHD for first conditioning to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) days; C, aGVHD for pre-transplant days; D, (acute and chronic) GVHD for admission day; E, (acute and chronic) GVHD for first conditioning to HSCT (FCH) days.

The AUC values indicate that CRP alone has weak discriminatory power and is not appropriate as a standalone predictive test. However, a low AUC does not preclude a statistically meaningful association when controlling for confounders. Multivariable regression models were therefore conducted to assess whether CRP independently contributes to aGVHD risk. The AUC for mean time from FCH for aGVHD was 54.1% (37.3 - 70.5) with sensitivity of 58.3% and specificity of 56.2%, and a cut-off of 5.8 mg/dL (Table 1 and Figure 1B). For the mean CRP in the interval between AH, the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity were 58.1% (42.9 - 73.3), 57.9%, and 61.1%, respectively, with a cut-off of 8.15 mg/dL (Table 1 and Figure 1C).

For GVHD on admission day, AUC was 56.7% (48.2– - 5.1), sensitivity 52.7%, and specificity 55.4%, with an optimal cut-off of 7 mg/dL (Figure 1D). During the period from FCH, the cut-off was 7.25 mg/dL (AUC 46.7%, sensitivity 50%, specificity 53%; Table 1, Figure 1E). These results demonstrate that the discriminatory ability of pre-transplant CRP is limited, especially during the conditioning-to-transplantation interval.

Although a statistical association was observed, this should not be interpreted as strong predictive performance, given the low AUC values. Regression analyses reflect adjusted associations rather than independent discriminative capability. Thus, while elevated CRP may be associated with increased aGVHD risk, CRP alone is not an adequate standalone predictor.

4.2. Predictive Value of Serum C-reactive Protein Before Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Overall Survival

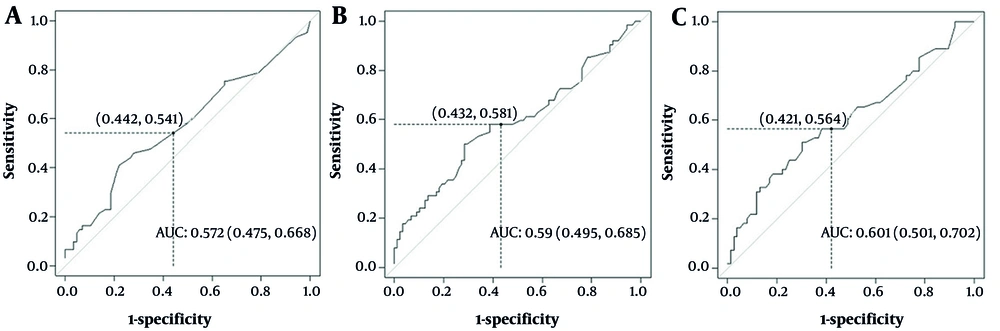

To determine the predictive value of pre-transplant CRP for OS, ROC analyses were performed. The AUC, sensitivity, and specificity on admission for OS were 57.2% (47.5 - 66.8), 54%, and 55.8%, with a cut-off of 7 mg/dL (Table 2, Figure 2A). For the interval from first conditioning to HSCT, the cut-off was 7.16 mg/dL (AUC 60.1%, sensitivity 56.3%, specificity 57.8%; Table 2, Figure 2B). For the interval between AH, the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity were 59% (49.5 - 68.5), 58%, and 56.8%, respectively, with a cut-off of 8 mg/dL (Table 2, Figure 2C). Considering these AUC percentages, serum CRP in the interval between conditioning and transplantation has limited utility for predicting OS.

| Period of Time | Thresholds | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC% (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admits | 7 | 54 | 55.8 | 57.2 (47.5 - 66.8) |

| First conditioning to HSCT OS | 7.16 | 56.3 | 57.8 | 60.1 (50.1 - 70.2) |

| Admit to HSCT OS | 8 | 58 | 56.8 | 59 (49.5 - 68.5) |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; CI, confidence interval; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; OS, overall survival.

4.3. Association of High Pre-transplant C-reactive Protein with Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease and Overall Survival

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses identified pre-transplant risk factors for aGVHD (Table 3). The CMV-positive recipients had 2.03-fold higher odds of aGVHD than CMV-negative recipients (75% CI: 1.36 - 3.03; P = 0.04). For each unit increase in transfused mononuclear cells (MNCs), the odds of aGVHD increased by 7%. Of the conditioning regimens, only BU+FLU was significantly associated with aGVHD, with 57% lower odds compared to CY+ATG (75% CI: 0.24 - 0.77; P = 0.09). Patients with high CRP had 30% higher odds of aGVHD compared to those with low CRP (75% CI: 1.11 - 1.61; P = 0.07). Other factors, such as recipient age, Body Mass Index (BMI), blood group, disease, prophylaxis regimen, and CD3+ T-cells, did not significantly affect aGVHD risk (Table 3).

| Variables | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (75% CI) | P-Value | AOR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Recipient age | 0.98 (0.97 - 1.004) | 0.39 | - | - |

| Recipient BMI | 0.39 | - | ||

| Below 18.5 | 2.01 (0.76 - 5.33) | 0.40 | - | - |

| Between 18.5 - 24.9 | 1.44 (0.83 - 2.47) | 0.43 | - | - |

| Between 25 - 29.9 | 0.76 (0.43 - 1.34) | 0.58 | - | - |

| Above 30 (RL) | - | - | - | - |

| Diagnosed disease | 0.90 | - | ||

| NHL | 1.69 (0.89 - 3.21) | 0.34 | - | - |

| AML | 1.05 (0.71 - 1.55) | 0.88 | - | - |

| ALL | 1.34 (0.87 - 2.07) | 0.43 | - | - |

| AA | 0.79 (0.34 - 1.81) | 0.74 | - | - |

| Other | 0.59 (0.19 - 1.78) | 0.58 | - | - |

| HD (RL) | - | - | - | - |

| Recipient CMV antigen | 0.04 a | 0.006 b | ||

| Positive | 2.03 (1.36 - 3.03) | 0.04 | 3.64 (1.44 - 9.81) | 0.006 |

| Negative (RL) | - | - | - | - |

| CD3 | 1.001 (0.99 - 1.004) | 0.82 | ||

| MNC | 1.07 (1.001 - 1.16) | 0.24 a | 0.95 (0.72 - 1.26) | 0.75 |

| Conditioning regimen | 0.21 a | 0.95 (0.72 - 1.26) | 0.75 | |

| Bu/Cy | 1.14 (0.71 - 1.84) | 0.74 | 55.63 (0-inf) | 0.98 |

| Bu/Fu | 0.43 (0.24 - 0.77) | 0.09 | 16.11 (0-inf) | 0.98 |

| Bu/Fu/ATG | 0.52 (0.25 - 1.09) | 0.31 | 4.68 (0-inf) | 0.99 |

| RIC | 1.94 (0.71 - 5.23) | 0.44 | 37.09 (0-inf) | 0.99 |

| CY+ATG (RL) | - | - | - | - |

| Prophylaxis regimen | 0.81 | - | ||

| CsA+MTX | 1.11 (0.66 - 1.85) | 0.81 | - | - |

| CsA+MTX+ATG (RL) | - | - | - | - |

| Blood group | 0.92 | - | ||

| A | 0.87 (0.51 - 1.48) | 0.76 | - | - |

| B | 0.75 (0.42 - 1.35) | 0.50 | - | - |

| AB | 1.74 (0.66 - 4.56) | 0.58 | - | - |

| O (RL) | - | - | - | - |

| CRP | 0.07 a | 0.05 b | ||

| > 8.15 | 1.3 (1.11 - 1.61) | 0.07 | 1.86 (1.44 - 9.18) | 0.05 |

| ≤ 8.15 (RL) | - | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, Body Mass Index; RL, reference level; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AA, aplastic anemia; CMV, cytomegalovirus; MNC, mononuclear cell; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; CRP, C-reactive protein; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; CsA, cyclosporine A; MTX, methotrexate.

a Significant at 0.25.

b Significant at 0.10.

Multivariable analysis indicated that recipient CMV antigen positivity and CRP level were significantly associated with aGVHD. Keeping other factors constant, CMV-positive recipients had 3.64 times greater odds of aGVHD than CMV-negative recipients (95% CI: 1.44 - 9.81; P = 0.006). Patients with high CRP had 86% greater odds of aGVHD compared to those with low CRP (95% CI: 1.44 - 9.18; P = 0.05; Table 3).

A Cox proportional hazards model was applied to identify significant risk factors for survival. Multivariable analysis indicated that patients with high pre-transplant CRP had a 2.74-fold higher risk of death than those with low CRP (95% CI: 1.02 - 7.38; P = 0.11), indicating a non-significant trend toward poorer OS (Table 4). Models were adjusted for established prognostic covariates to minimize confounding. All effect estimates are presented with 95% CIs.

| Variable | AHR | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP | 1.02 - 7.38 | 0.11 b | |

| > 8 | 2.74 | ||

| ≤ 8 (RL) | - |

Abbreviations: AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; RL, reference level.

a Factors included in univariable analysis: Patient gender, patient age, donor-patient gender, recipient cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigen, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis, diagnosis, antithymocyte globulin (ATG), conditioning regimen.

b Significant at 0.12.

4.4. Association of Risk Factors with High Pre-transplant C-reactive Protein

As shown in Table 5, the median age of recipients with low-risk CRP was 30, compared to 34 for those with high CRP. Five (5.2%) low-risk and 13 (16.3%) high-risk patients received ATG. The frequency of ATG as part of the prophylaxis regimen was significantly higher among high CRP patients (odds ratio: 1.73; 95% CI: 1.25 - 2.39; P = 0.04). The remaining variables did not show significant associations.

| Variables | CRP | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (≤ 8.15, N = 96) | High (> 8.15, N = 80) | |||

| Recipient age; No. (Median) | 30 (19 - 50) | 34 (16 - 51) | 1.005 (0.98 - 1.02) | 0.70 |

| Missing | 4 (4.2) | 2 (2.5) | - | - |

| Recipient gender | 0.19 b | |||

| Male | 51 (43.8) | 36 (45) | 0.82 (0.78 - 1.42) | 0.19 |

| Female (RL) | 42 (53.1) | 44 (55) | - | - |

| Missing | 3 (3.1) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| Diagnosed disease | 0.26 | |||

| NHL | 5 (5.2) | 6 (7.5) | 0.10 (0 - > 999) | 0.96 |

| AML | 50 (52.1) | 34 (42.5) | 0.06 (0 - > 999) | 0.95 |

| ALL | 29 (30.2) | 17 (21.3) | 0.05 (0 - > 999) | 0.95 |

| AA | 1 (1) | 7 (8.8) | 0.61 (0 - > 999) | 0.99 |

| Other | 0 (0) | 7 (6.3) | > 1000 (0 - > 999) | 0.96 |

| HD (RL) | 5 (5.2) | 6 (7.5) | - | - |

| Missing | 6 (6.3) | 5 (61) | - | - |

| Recipient CMV antigen | 0.34 | |||

| Positive | 7 (7.3) | 3 (3.8) | 1.18 (0.74 - 1.88) | 0.34 |

| Negative (RL) | 40 (41.7) | 34 (42.5) | - | - |

| Missing | 49 (51) | 43 (53.8) | - | - |

| Conditioning regimen | 0.99 | |||

| Bu/Cy | 55 (57.3) | 37 (46.3) | 0.005 (0 - > 999) | 0.97 |

| Bu/Fu | 23 (24) | 15 (18.8) | 0.006 (0 - > 999) | 0.97 |

| Bu/Fu/ATG | 3 (3.1) | 11 (13.8) | > 1000 (0 - > 999) | 0.97 |

| RIC | 1 (1) | 3 (3.8) | 0.005 (0 - > 999) | 0.97 |

| CY+ATG (RL1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.5) | - | - |

| Missing | 14 (14.6) | 12 (15) | - | - |

| Prophylaxis regimen | 0.04 b | |||

| CsA+MTX+ATG | 5 (5.2) | 13 (16.3) | 1.73 (1.25 - 2.39) | 0.04 |

| CsA+MTX (RL) | 58 (60.4) | 50 (62.5) | - | - |

| Missing | 33 (34.4) | 17 (21.2) | - | - |

| Blood group | 0.80 | |||

| A | 30 (31.3) | 21 (26.3) | 0.94 (0.57 - 1.53) | 0.87 |

| B | 17 (17.7) | 19 (23.8) | 0.64 (0.40 - 1.21) | 0.40 |

| AB | 12 (12.5) | 9 (11.2) | 1.16 (0.53 - 2.52) | 0.80 |

| O (RL) | 30 (31.2) | 26 (32.4) | - | - |

| Missing | 7 (7.3) | 5 (6.3) | - | - |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; RL, reference level; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AA, aplastic anemia; CMV, cytomegalovirus; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; CsA, cyclosporine A; MTX, methotrexate.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless indicated.

b Significant at 0.25.

4.5. Survival Analyses by Risk Groups

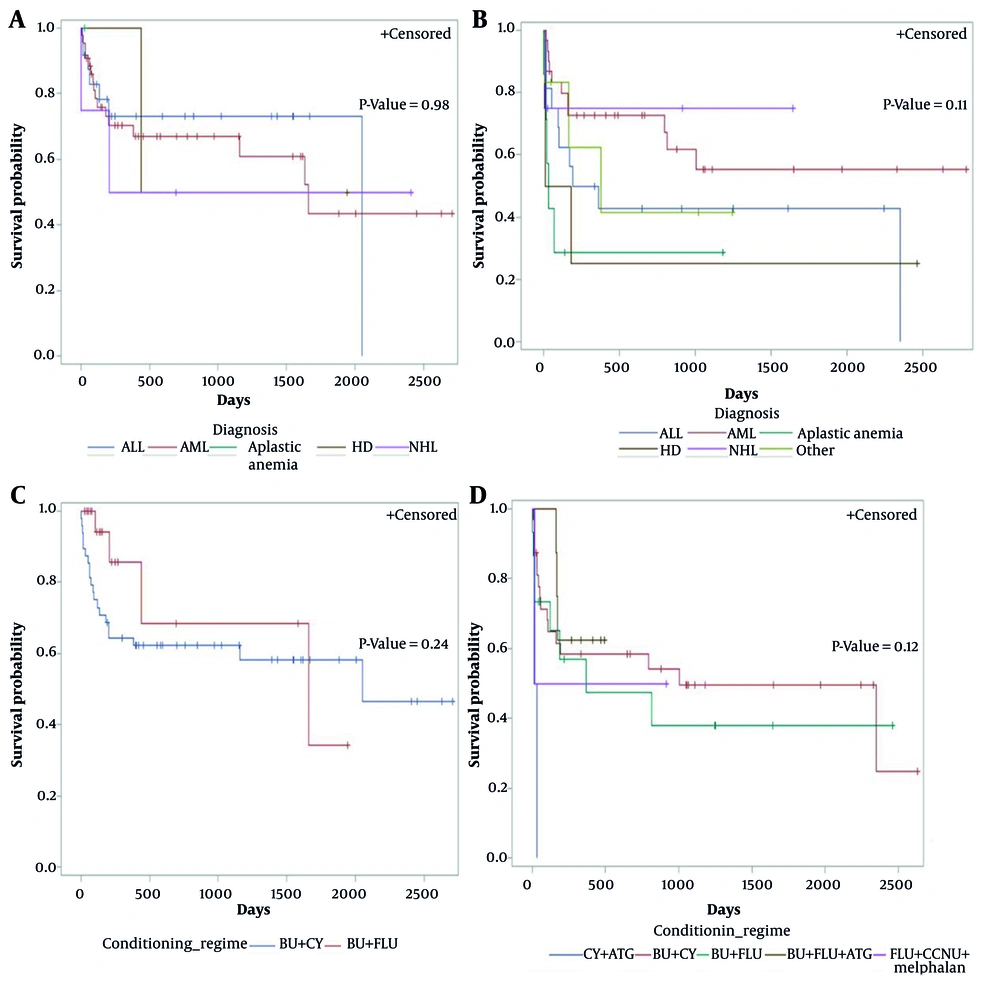

Figure 3 presents Kaplan-Meier curves for OS stratified by CRP risk group, conditioning regimen, and diagnosis. For low-risk CRP, there was no significant difference in OS by diagnosis (P = 0.98, Figure 3A). Among high-risk CRP patients, OS did not differ significantly between diagnoses (P = 0.11, Figure 3B). No significant difference in OS was observed between conditioning regimens among high-risk (P = 0.24, Figure 3C) or low-risk CRP groups (P = 0.12, Figure 3D).

Overall survival (OS) after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in each C-reactive protein (CRP) risk group by conditioning regimen and diagnosis: A, OS for low-risk CRP level by diagnosis; B, OS for high CRP level by diagnosis; C, OS for high CRP level by conditioning regimen; D, OS for low-risk CRP level by conditioning regimen.

5. Discussion

Developing reliable strategies to predict post-transplant outcomes is crucial for reducing complications such as GVHD and mortality (15). Previous studies have shown associations between serum biomarkers and HSCT outcomes. Among inflammatory markers, CRP, interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), interleukin-2 receptor alpha (IL-2Ra), procalcitonin (PCT), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) are considered key candidates for predicting adverse post-transplant events (16, 17). The CRP is an acute-phase protein produced mainly by hepatocytes, rising in response to infection, inflammation, or tissue injury. Recent data highlight the possible prognostic value of pre-transplant CRP in HSCT recipients (18).

In this study, CRP demonstrated poor predictive accuracy for aGVHD, overall GVHD, and OS across all three analyzed time intervals, suggesting that elevated CRP alone is insufficient as a standalone biomarker for adverse outcomes. Because the multivariable models were adjusted for established prognostic variables — including age, donor type, HLA match, conditioning regimen, graft source, CMV serostatus, ATG administration, and disease status — the observed associations likely reflect an independent inflammatory contribution rather than confounding (19).

The association between high CRP and ATG exposure is most likely due to confounding from transplant biology, as ATG is preferentially administered to patients with mismatched donors and heightened baseline inflammation. Thus, elevated CRP may act as a surrogate marker of the host–donor inflammatory milieu rather than a direct predictor of outcomes. This interpretation is consistent with recent reports suggesting that pre-transplant inflammatory biomarkers primarily serve as contextual indicators of biological vulnerability, gaining prognostic relevance only when integrated with other clinical or immunologic variables (20, 21).

The CRP threshold on admission day (7 mg/dL) was derived using the Youden Index, providing the most balanced sensitivity and specificity and allowing reproducible group classification for analysis. Although discriminative performance was modest, this method enabled data-driven classification. The discrepancy between low AUC and regression findings reflects the different statistical approaches: The ROC curves assess univariable discriminatory power, while regression models assess adjusted associations. Therefore, a biomarker may have limited discriminative power yet still retain a relevant adjusted association.

Taken together, these results indicate that CRP mostly reflects pre-transplant inflammation rather than providing reliable outcome prediction. While biologically plausible links exist between high CRP and adverse outcomes, its ability to discriminate is limited on its own. The CRP should be considered an inflammatory risk indicator, providing added prognostic information when combined with other variables rather than serving as a standalone marker. All estimates were recalculated with 95% CIs to better capture statistical uncertainty.

This study found that high pre-transplant CRP was associated with increased aGVHD and a non-significant trend toward inferior OS. Pihusch et al. reported similar results, identifying CRP, IL-6, and PCT as potential prognostic markers. Elevated CRP and IL-6, with modestly increased PCT during conditioning, were linked to higher mortality from aGVHD and infection. Elevated CRP in aGVHD was not solely due to infection or steroid use (19). Artz et al. also demonstrated prognostic value for pre-conditioning proinflammatory markers, with increased CRP associated with higher mortality, morbidity, and reduced post-transplant tolerance, including hepatic toxicity, longer hospitalization, severe aGVHD, higher non-relapse death, and worse OS (20). These findings support that pre-transplant inflammation, reflected by high CRP, might contribute to toxicity and GVHD risk.

Proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines are implicated in aGVHD pathogenesis, and their effects may be influenced by donor and recipient cytokine genetics (22). Genetic polymorphisms in CRP-coding genes may result in interindividual differences in inflammatory responses. Prior studies support that inflammatory cytokines induced by conditioning-related tissue injury may correlate with aGVHD incidence. Elevated serum CRP may reflect an inflammatory environment conducive to complement activation, endothelial damage, and aGVHD induction (23). The IL-6 can stimulate hepatocyte CRP synthesis, acting as a regulatory cytokine. When patients with high pre-transplant CRP receive donor T-cells, CRP-mediated T-cell activation may damage endothelial and epithelial cells, contributing to aGVHD (23, 24).

A retrospective study by Yanada et al. showed that 241 HSCT patients with aGVHD were at significantly higher risk for developing CMV antigenemia (25). Cantoni et al. found an increased risk for CMV replication in patients with higher-grade GVHD (26). Our results revealed a significant association between CMV positivity and aGVHD, consistent with existing literature and possibly attributable to the immunosuppressive regimen prior to transplantation.

Jordan et al. found that poor OS was associated with CRP above 10 mg/dL; high CRP, diagnosis, older age, and ATG administration were poor prognostic factors in multivariate analysis (12). In our analysis, only high CRP was linked to reduce OS. Our findings also agree with Fuji et al., who reported an association between high CRP and poor survival. In our cohort, only half of high CRP patients were male, and most patients receiving ATG had high CRP (27). Letermovir, currently approved for CMV prophylaxis in Allo-HSCT, is not yet available in our center (28).

A statistically significant correlation between high serum CRP and ATG prophylaxis was observed, consistent with findings by Jordan et al. (12) and Pihusch et al., who reported a sixfold increase in CRP for ATG recipients (19). The ATG toxicity may contribute to increase CRP, as ATG administration can result in infection, skin rash, fever, and thrombocytopenia (29).

Regarding conditioning regimens, patients receiving BU+FLU had significantly lower odds of aGVHD than those receiving other regimens. Fuji et al. also found lower acute and chronic GVHD frequency and severity with BU+FLU compared to BU+CY (27). However, Lin et al. and Liu et al. found no significant association between conditioning regimen and aGVHD (28, 30). Less host tissue damage by fludarabine may explain the reduced GVHD incidence with BU+FLU.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that elevated pre-transplant serum CRP levels are associated with a higher incidence of aGVHD and demonstrate a non-significant trend toward inferior OS. Although CRP reflects pre-transplant inflammation, it does not meet the criteria for a validated prognostic biomarker, with only modest association with aGVHD and no statistically significant link with OS.

The CRP should thus be regarded as an informative yet insufficient biomarker. While it may add prognostic value when assessed alongside other clinical or biological variables, it cannot serve as a standalone predictor based solely on pre-transplant levels. Instead, its utility should be considered within a composite, multi-parameter predictive framework. This aligns with contemporary Allo-HSCT research, which emphasizes integrative biomarker models and external validation over reliance on single laboratory measures.

Despite limitations such as retrospective design and small sample size, CRP measurement remains a simple, affordable, and non-invasive candidate for inclusion in multi-marker prognostic panels. Future prospective studies with larger cohorts are required to validate these findings and to identify additional biomarkers that may improve prediction of post-transplant outcomes (31, 32).