1. Background

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) results from infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (1). The HIV remains a major global public health concern (2, 3), particularly in developing contexts such as Iran (4, 5). Beyond its biomedical effects, the disease imposes profound social and psychological challenges on affected individuals (6). People living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH) are especially vulnerable to psychological and social difficulties compared to the general population, making psychological interventions a critical component of comprehensive care (7).

Two of the most common and debilitating psychological consequences of HIV are heightened self-blame and diminished distress tolerance. Distress tolerance, defined as an individual’s ability to endure and manage negative emotional states, plays a central role in the onset and maintenance of psychological disorders (8). The PLWH frequently encounter distress related to their diagnosis, experiences of social stigma, and uncertainty regarding health outcomes, all of which may overwhelm their coping resources (9). According to Simons and Gaher, distress tolerance encompasses the ability to endure aversive emotional states, the acceptance of negative affect, the use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies, and the extent to which negative emotions disrupt daily functioning (10).

Similarly, self-blame represents another major psychological burden in this population. It is generally defined as a cognitive process in which individuals attribute negative events to internal causes, often accompanied by overly critical self-evaluations and unrealistically high self-expectations (11, 12). Among PLWH, self-blame may be further intensified by shame and self-criticism associated with the illness, which can erode hope and adversely affect recovery and well-being (13).

In general, individuals with chronic medical conditions, including PLWH, experience greater psychological and social vulnerability than the general population (14). Consequently, psychological interventions play a vital role in managing mental health difficulties in this population (15). Given these challenges, the present study evaluates two therapeutic approaches: Schema therapy (ST) and compassion-focused therapy (CFT).

The ST is an integrative approach aimed at identifying and modifying deeply ingrained maladaptive schemas and coping styles that arise from unmet core emotional needs (16). For PLWH, it is hypothesized to be effective by addressing core beliefs of defectiveness or shame that often underlie self-blame (17). Previous research supports the effectiveness of ST in altering maladaptive cognitive patterns that contribute to psychological distress (18).

The CFT, in contrast, was developed to enhance emotional and psychological well-being by fostering compassion toward oneself and others. Its core principles emphasize the internalization of soothing experiences, thoughts, and images, such that the mind responds with calmness in a manner similar to external sources of comfort (19, 20). Rather than directly attempting to change self-evaluations, it seeks to transform the individual’s relationship with these evaluations (21). It was specifically designed to address elevated levels of shame and self-criticism (22, 23) by cultivating self-compassion and promoting a more supportive internal response to distress (24). By activating the brain’s self-soothing system, CFT is theorized to strengthen emotion regulation capacities and enhance distress tolerance (25). Empirical studies have further indicated its potential to improve distress tolerance and overall psychological well-being in diverse populations (26).

2. Objectives

Despite the theoretical promise of both approaches, their comparative effectiveness among PLWH has not yet been systematically examined. Considering that the psychological needs of this population are often underrecognized, the present study was conducted to compare the effectiveness of ST and CFT in reducing self-blame and enhancing distress tolerance.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Randomization

This study employed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design with pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up assessments. It included two experimental groups (ST and CFT) and a control group. The study was conducted during the 2022 - 2023 academic year. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three groups using a computer-generated random number sequence. Allocation was concealed through sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes prepared by an independent researcher who was not involved in participant recruitment. Outcome assessors were blinded to group assignments at all measurement points.

3.2. Participants

A total of 60 individuals living with HIV, who had medical records at the Behavioral Diseases Counseling Center of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran, participated in the study. Initial recruitment was conducted using purposive sampling. Inclusion criteria were: A formal diagnosis of HIV, age between 25 and 45 years, and the ability to attend all therapy sessions. Exclusion criteria included concurrent participation in other psychotherapy, the presence of acute psychiatric or medical illness during the study, or missing more than two therapy sessions.

3.3. Sample Size Calculation

An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 to determine the required sample size. For a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with three groups and three measurement points, assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25), an alpha level of 0.05, and a power of 0.80, the analysis indicated that 54 participants were required. To account for potential attrition, a total of 60 participants were recruited, with 20 allocated to each group.

3.4. Interventions

Participants in the experimental groups received eight weekly 90-minute group therapy sessions. The control group did not receive any psychological intervention during the study period but was offered treatment after the follow-up assessment.

3.4.1. Schema Therapy

Sessions were conducted according to Young et al. and focused on identifying maladaptive schemas, understanding their origins, and using cognitive, experiential, and behavioral techniques to modify them (Table 1) (16).

| Sessions | Session Content |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | Establishing rapport and building a therapeutic alliance, introducing the importance and purpose of ST, and discussing clients’ presenting problems within the ST framework |

| Session 2 | Examining objective evidence that supports or contradicts the client’s schemas, based on both current life experiences and past events; engaging in discussions to contrast the maladaptive schema with a healthy alternative schema |

| Session 3 | Teaching cognitive techniques, such as: Validity testing of existing schemas, reframing the evidence that supports the maladaptive schema, evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of the individual’s coping styles |

| Session 4 | Enhancing the concept of the “healthy adult” within the client’s mind, identifying unmet emotional needs, and providing strategies for emotional expression, such as releasing blocked emotions and learning healthy communication, including guided imagery dialogues |

| Session 5 | Teaching experiential techniques, such as: Imagery rescripting for distressing or problematic situations, practicing emotional confrontation with the most triggering scenarios |

| Session 6 | Developing therapeutic relationships, practicing interpersonal skills with significant others, and using role-play exercises to simulate healthy behaviors; assigning homework to reinforce new, adaptive behavioral patterns |

| Session 7 | Discussing the pros and cons of healthy versus unhealthy behaviors, and offering practical strategies to overcome barriers to behavioral change |

| Session 8 | Reviewing the content of previous sessions, summarizing key points, and practicing the strategies learned to enhance retention and application in daily life |

Abbreviation: ST, schema therapy.

3.4.2. Compassion-Focused Therapy

Sessions followed Gilbert’s protocol and included psychoeducation on the three emotional regulation systems, mindfulness exercises, and strategies to cultivate a compassionate mind and reduce self-blame (Table 2) (21).

| Sessions | Session Content |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | Pre-test administration: Introduction of the therapist and group members to one another, discussion of the purpose and structure of the sessions, clarification of expectations for the first therapeutic session; introduction to the basic principles of CFT and the distinction between compassion and self-pity |

| Session 2 | Explanation and conceptualization of compassion — "what compassion is and how it can help us overcome psychological challenges"; introduction to mindfulness with practical exercises including body scanning and focused breathing; Familiarization with the compassion-based emotion regulation systems of the brain |

| Session 3 | Understanding the characteristics of compassionate individuals, developing compassion for others, cultivating warmth and kindness toward the self, and recognizing that others also have flaws and struggles (developing a sense of common humanity) — as opposed to engaging in self-critical and destructive thoughts |

| Session 4 | Training in developing warmth, energy, acceptance, wisdom, power, and nonjudgmental awareness. Instruction on various modes of expressing compassion (e.g., verbal, behavioral, short-term, sustained), and how to apply these in daily life, especially in interactions with parents, friends, and acquaintances |

| Session 5 | Encouraging self-awareness and reflection on one’s personality in terms of being a “compassionate” or “non-compassionate” person. Identification of personal obstacles and practice of “cultivating a compassionate mind” through exercises emphasizing the value of compassion, empathy, and sympathy toward self and others |

| Session 6 | Training in core compassionate competencies, including: Compassionate attention, compassionate reasoning, compassionate behavior, compassionate imagery, compassionate feelings, compassionate sensing/perception, role-playing using the Gestalt empty chair technique to explore three inner parts: The self-critical voice, the criticized self, and the compassionate self. Participants are guided to recognize the tone, language, and patterns of these voices and connect them to early relational templates, such as parental communication styles. |

| Session 7 | Completion of a weekly self-monitoring chart that records: Self-critical thoughts, compassionate thoughts, compassionate behaviors, exploration of color, space, and music associated with the compassionate self (to be used in compassion-focused imagery); Addressing fears of self-compassion and obstacles to developing a compassionate attitude; training in additional techniques such as: Compassion-focused imagery, rhythmic soothing breathing, mindfulness practice, and writing a self-compassionate letter |

| Session 8 | Final summary and review of key therapeutic content, open Q&A, and discussion of members' experiences; Expression of gratitude to participants for their involvement; post-test administration to assess outcomes of the intervention |

Abbreviation: CFT, compassion-focused therapy.

3.5. Therapist Training and Intervention Fidelity

Group therapy sessions for both interventions were delivered by a licensed clinical health psychologist who received specialized training for this study. For ST, she completed a 100-hour theoretical workshop and a 70-hour practical supervision workshop with certification. For CFT, she participated in a 70-hour training workshop, including 20 hours of supervised practice under the guidance of a certified CFT instructor.

To ensure intervention fidelity, 15% of therapy sessions were randomly selected, audio-recorded, and reviewed by an independent supervisor trained in both modalities. Weekly supervision meetings were held to monitor adherence to the treatment manuals and address any implementation challenges.

3.6. Measures

1. Self-blame Scale: Developed by Thompson and Zuroff (2004), this 22-item scale assesses two components of self-blame: Internalized self-blame and comparative self-blame.

2. Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS): Developed by Simons and Gaher (2005), this 15-item self-report measure evaluates an individual’s perceived ability to tolerate emotional distress across four subscales: Tolerance, absorption, appraisal, and regulation.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Karaj Branch (code: IR.IAU.K.REC.1401.119). All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. Participation was voluntary, and confidentiality of data was strictly maintained throughout the study.

3.8. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were used to summarize demographic and study variables. A mixed-design repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of time, group, and the time × group interaction on the outcome variables. Assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test), and homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices (Box’s M test) were assessed and met. When the assumption of sphericity was violated (Mauchly’s test), the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni post-hoc test. While this approach is stringent in controlling for type I error, its conservative nature was considered when interpreting results. Partial eta squared (η2) was reported as a measure of effect size.

4. Results

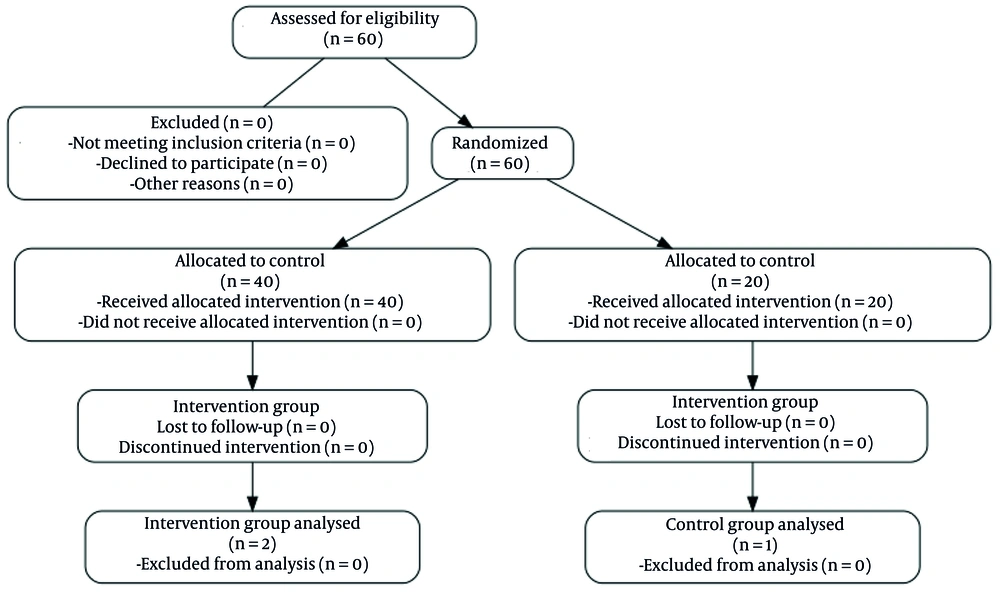

The following flow diagram summarizes the progress of participants through the phases of the randomized trial, as required by the CONSORT 2025 guidelines (Figure 1).

4.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 60 patients with HIV were included in the final analysis. The mean age was 33.33 ± 4.34 years in the control group, 33.77 ± 4.47 years in the ST group, and 34.13 ± 5.11 years in the CFT group. There were no significant baseline differences in age or educational level among the three groups (P > 0.05).

- Enrollment: Assessed for eligibility (n = 85) → excluded (n = 25) → randomized (n = 60).

- Allocation: Allocated to ST (n = 20), CFT (n = 20), and control (n = 20).

- Follow-up: Completed 3-month follow-up (n = 20 for all groups).

- Analysis: Analyzed (n = 20 for all groups).

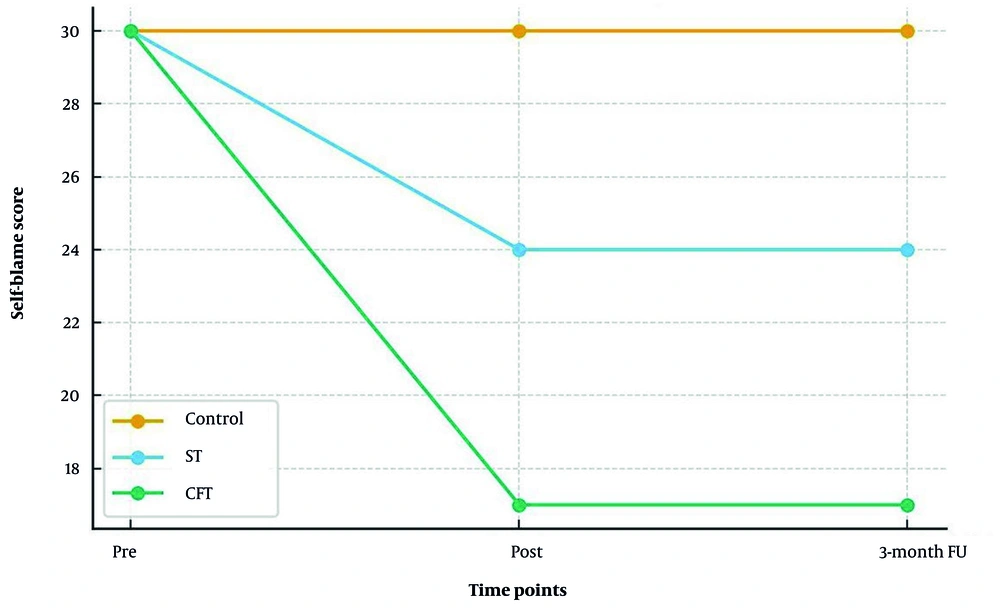

4.2. Effects of Interventions on Self-blame

A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant time × group interaction for total self-blame (F (2.29, 1700.79) = 66.12, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.69), indicating that changes over time differed significantly across groups. Bonferroni post-hoc tests showed that both the ST group (mean difference = 6.0, P = 0.001) and the CFT group (mean difference = 12.71, P = 0.014) experienced significant reductions in self-blame compared to the control group. Additionally, the CFT group demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in self-blame than the ST group (mean difference = -6.71, P = 0.005). These improvements were maintained at the three-month follow-up for both intervention groups (Figure 2).

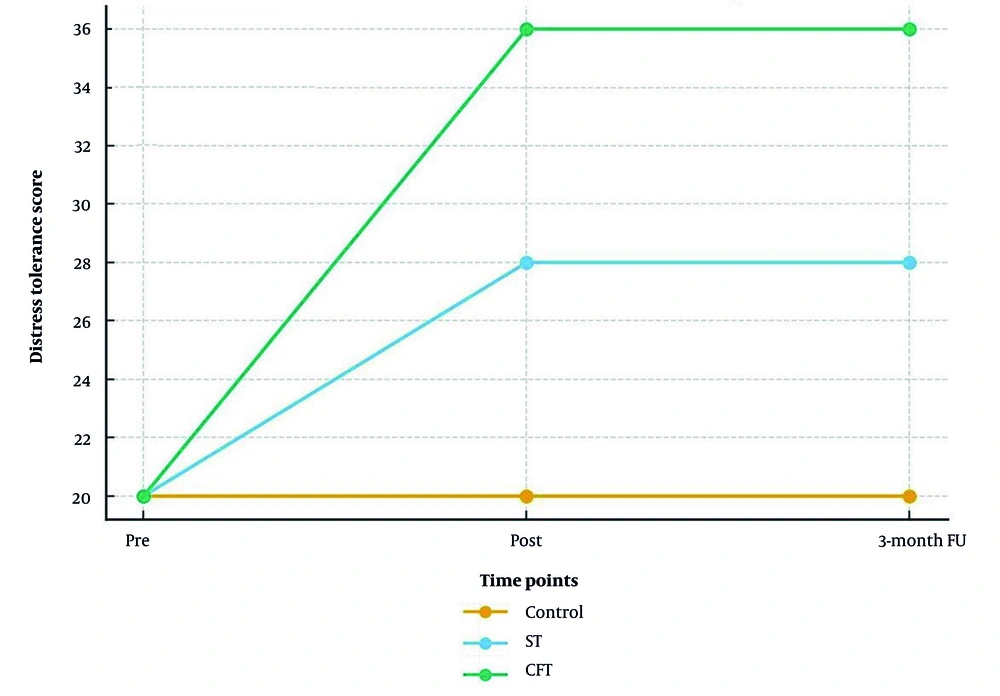

4.3. Effects of Interventions on Distress Tolerance

A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant time × group interaction for total distress tolerance (F (3.27, 1257.88) = 46.58, P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.62), indicating that changes in distress tolerance over time differed by group. Bonferroni post-hoc tests indicated that both the ST group (mean difference = 8.15, P < 0.001) and the CFT group (mean difference = 16.26, P < 0.001) demonstrated significant increases in distress tolerance compared to the control group. Furthermore, the CFT group exhibited a significantly greater increase in distress tolerance than the ST group (mean difference = 8.11, P < 0.001). These improvements were maintained at the three-month follow-up (Figure 3).

In this study, 60 patients diagnosed with HIV were randomly assigned to three groups: The ST, CFT, and a control group. The mean age of participants was 33.33 ± 4.34 years in the control group, 33.77 ± 4.47 years in the ST group, and 34.13 ± 5.11 years in the CFT group. There were no significant differences in educational level among the three groups (P > 0.05). Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations of self-blame and its subcomponents at the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages across the three groups.

| Variables | Measurement Stages | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up | |

| Self-blame | |||

| ST | 65.78 ± 58.5 | 40.68 ± 11.5 | 20.68 ± 15.5 |

| CFT | 75.78 ± 91.7 | 10.58 ± 28.7 | 25.58 ± 6.7 |

| Control | 4.77 ± 39.8 | 30.79 ± 33.5 | 55.78 ± 1.5 |

| Internalized self-blame | |||

| ST | 05.38 ± 85.3 | 40.33 ± 07.3 | 1.33 ± 74.3 |

| CFT | 45.37 ± 17.4 | 70.28 ± 44.3 | 50.28 ± 92.4 |

| Control | 65.37 ± 51.5 | 60.38 ± 2.4 | 38 ± 21.4 |

| Comparative self-blame | |||

| ST | 6.40 ± 43.4 | 35 ± 50.4 | 1.35 ± 28.4 |

| CFT | 30.41 ± 41.4 | 40.29 ± 12.5 | 75.29 ± 74.4 |

| Control | 85.39 ± 79.5 | 70.40 ± 54.3 | 55.40 ± 41.3 |

Abbreviations: ST, schema therapy; CFT, compassion-focused therapy.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Table 4 shows the means and standard deviations of distress tolerance and its subcomponents at the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages across the three groups.

| Variables | Measurement Stages | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up | |

| Distress tolerance | |||

| ST | 35.4 ± 09.1 | 15.9 ± 39.1 | 30.8 ± 13.2 |

| CFT | 15.5 ± 18.1 | 95.11 ± 05.1 | 80.11 ± 01.1 |

| Control | 85.4 ± 57.1 | 15.5 ± 18.1 | 15.5 ± 03.2 |

| Absorption by negative emotions | |||

| ST | 60.4 ± 10.1 | 85.8 ± 09.1 | 65.8 ± 18.1 |

| CFT | 20.4 ± 74.1 | 85.11 ± 23.1 | 95.10 ± 67.2 |

| Control | 10.4 ± 86.1 | 45.4 ± 76.1 | 90.4 ± 40.2 |

| Appraisal of distress | |||

| ST | 60.5 ± 43.1 | 55.9 ± 99.1 | 25.9 ± 34.2 |

| CFT | 50.5 ± 54.1 | 70.12 ± 81.1 | 15.12 ± 80.2 |

| Control | 75.5 ± 52.1 | 55.5 ± 32.1 | 90.5 ± 13.2 |

| Distress alleviation | |||

| ST | 20.5 ± 24.1 | 05.9 ± 85.1 | 80.8 ± 17.2 |

| CFT | 55.4 ± 67.1 | 45.11 ± 5.2 | 25.11 ± 61.2 |

| Control | 70.4 ± 66.1 | 05.5 ± 16.2 | 30.5 ± 20.2 |

Abbreviations: ST, schema therapy; CFT, compassion-focused therapy.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Table 5 presents the results of Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances between groups. The obtained F-values for the total self-blame score and its subcomponents were not statistically significant, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variances was satisfied.

| Variables | F | df1 | df2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-blame | ||||

| Pre-test | 74.2 | 2 | 57 | 07.0 |

| Post-test | 10.1 | 2 | 57 | 33.0 |

| Follow-up | 11.1 | 2 | 57 | 33.0 |

| Internalized self-blame | ||||

| Pre-test | 19.0 | 2 | 57 | 82.0 |

| Post-test | 90.0 | 2 | 57 | 41.0 |

| Follow-up | 28.0 | 2 | 57 | 75.0 |

| Comparative self-blame | ||||

| Pre-test | 14.0 | 2 | 57 | 86.0 |

| Post-test | 75.1 | 2 | 57 | 18.0 |

| Follow-up | 72.1 | 2 | 57 | 18.0 |

Table 6 presents the results of Box’s M test. The obtained F-values for the total self-blame score and its subcomponents were not statistically significant, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices across groups was satisfied.

| Variables | Box’s M | F | df1 | df2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-blame | 47.21 | 38.2 | 12 | 15.15745 | 217.0 |

| Internalized self-blame | 35.20 | 45.2 | 12 | 15.15745 | 201.0 |

| Comparative self-blame | 72.22 | 98.2 | 12 | 15.15745 | 097.0 |

Results from Mauchly’s test of sphericity (Table 7) indicated that the chi-square values for the variables were not statistically significant. Therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied when reporting the findings.

| Variables | Mauchly | χ2 | df | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-blame | 258.0 | 83.75 | 2 | 001.0 |

| Internalized self-blame | 868.0 | 92.7 | 2 | 019.0 |

| Comparative self-blame | 660.0 | 29.23 | 2 | 001.0 |

Table 8 presents the results of the repeated measures ANOVA. The within-subject effect of time was statistically significant for self-blame (F = 113.05, P < 0.01), internalized self-blame (F = 153.37, P < 0.01), and comparative self-blame (F = 159.66, P < 0.01), indicating significant differences across the three measurement stages (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up). The time × group interaction was also significant for self-blame (F = 66.12, P < 0.01), internalized self-blame (F = 61.63, P < 0.01), and comparative self-blame (F = 68.79, P < 0.01). Furthermore, the between-subject effect of group reached statistical significance for self-blame (F = 19.34, P < 0.01), internalized self-blame (F = 13.48, P < 0.01), and comparative self-blame (F = 13.21, P < 0.01).

| Variables | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-blame | ||||||

| Between-subjects | ||||||

| Time | 84.3338 | 148.1 | 83.2907 | 05.113 | 001.0 | 66.0 |

| Time × group | 78.3905 | 29.2 | 79.1700 | 12.66 | 001.0 | 69.0 |

| Within-subjects | ||||||

| Group | 54.4856 | 2 | 27.2428 | 34.19 | 001.0 | 40.0 |

| Internalized self-blame | ||||||

| Between-subjects | ||||||

| Time | 14.755 | 76.1 | 40.427 | 37.153 | 001.0 | 72.0 |

| Time × group | 88.606 | 53.3 | 74.171 | 63.61 | 001.0 | 68.0 |

| Within-subjects | ||||||

| Group | 57.1280 | 2 | 28.640 | 48.13 | 001.0 | 32.0 |

| Comparative self-blame | ||||||

| Between-subjects | ||||||

| Time | 30.1210 | 40.1 | 05.811 | 66.159 | 001.0 | 73.0 |

| Time × group | 96.1042 | 98.2 | 46.349 | 79.68 | 001.0 | 70.0 |

| Within-subjects | ||||||

| Group | 43.1421 | 2 | 71.710 | 21.13 | 001.0 | 31.0 |

Abbreviations: SS, sum of squares; MS, mean square.

Table 9 presents the results of the Bonferroni post-hoc test for pairwise comparisons at each measurement stage for self-blame and its subcomponents. Self-blame scores significantly decreased from pre-test to both post-test and follow-up, with no significant difference between post-test and follow-up. For internalized self-blame, significant reductions were observed between pre-test and both subsequent stages. Similarly, comparative self-blame showed significant decreases from pre-test to post-test and follow-up, with stability between the latter two stages.

| Variables | Mean Difference | Standard Error | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-blame | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | 9.0 a | 83.0 | 001.0 |

| Follow-up | 26.9 a | 83.0 | 001.0 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | 267.0 | 26.0 | 93.0 |

| Internalized self-blame | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | 15.4 a | 25.0 | 001.0 |

| Follow-up | 51.4 a | 33.0 | 001.0 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | 367.0 | 262.0 | 50.0 |

| Comparative self-blame | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | 55.5 a | 37.0 | 001.0 |

| Follow-up | 45.5 a | 42.0 | 001.0 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | -231.0 | 24.0 | 1 |

| Self-blame | |||

| ST | |||

| CFT | -71.6 a | 04.2 | 005.0 |

| Control | -6 a | 04.2 | 001.0 |

| CFT | |||

| Control | -71.12 a | 04.2 | 014.0 |

| Internalized self-blame | |||

| ST | |||

| CFT | -30.3 a | 25.1 | 033.0 |

| Control | -23.3 a | 25.1 | 001.0 |

| CFT | |||

| Control | -53.6 a | 25.1 | 038.0 |

| Comparative self-blame | |||

| ST | |||

| CFT | -41.3 a | 33.1 | 040.0 |

| Control | -46.3 a | 33.1 | 001.0 |

| CFT | |||

| Control | -88.6 a | 33.1 | 037.0 |

Abbreviations: ST, schema therapy; CFT, compassion-focused therapy.

a Statistically significant difference based on the Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc test (P < 0.001).

Table 10 presents the results of Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances across groups. The obtained F-values for the total distress tolerance score and its subcomponents were not statistically significant, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variances was satisfied.

| Variables | F | df1 | df2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distress tolerance (total) | ||||

| Pre-test | 40.2 | 2 | 57 | 056.0 |

| Post-test | 07.3 | 2 | 57 | 054.0 |

| Follow-up | 16.0 | 2 | 57 | 85.0 |

| Distress tolerance | ||||

| Pre-test | 56.0 | 2 | 57 | 57.0 |

| Post-test | 31.1 | 2 | 57 | 27.0 |

| Follow-up | 79.0 | 2 | 57 | 45.0 |

| Negative emotion absorption | ||||

| Pre-test | 37.1 | 2 | 57 | 26.0 |

| Post-test | 62.2 | 2 | 57 | 08.0 |

| Follow-up | 14.2 | 2 | 57 | 12.0 |

| Subjective appraisal | ||||

| Pre-test | 12.0 | 2 | 57 | 88.0 |

| Post-test | 419.0 | 2 | 57 | 66.0 |

| Follow-up | 19.0 | 2 | 57 | 82.0 |

| Distress relief | ||||

| Pre-test | 73.0 | 2 | 57 | 46.0 |

| Post-test | 70.0 | 2 | 57 | 50.0 |

| Follow-up | 50.0 | 2 | 57 | 60.0 |

Table 11 presents the results of Box’s M test. The obtained F-values for the total distress tolerance score and its subcomponents were not statistically significant, indicating that the assumption of homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices across groups was satisfied.

| Variables | Box’s M | F | df1 | df2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total distress tolerance score | 13.25 | 03.2 | 12 | 15.15745 | 426.0 |

| Distress tolerance | 21.23 | 11.2 | 12 | 15.15745 | 351.0 |

| Absorption of negative emotions | 30.24 | 13.1 | 12 | 15.15745 | 343.0 |

| Subjective appraisal of distress | 72.18 | 09.1 | 12 | 15.15745 | 245.0 |

| Distress relief | 27.19 | 36.1 | 12 | 15.15745 | 455.0 |

Table 12 presents the results of Mauchly’s test of sphericity. The obtained chi-square values for the variables were not statistically significant; therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied in reporting the results.

| Variables | Mauchly | χ2 | df | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total distress tolerance score | 77.0 | 97.13 | 2 | 001.0 |

| Distress tolerance | 88.0 | 77.6 | 2 | 034.0 |

| Absorption of negative emotions | 75.0 | 83.15 | 2 | 001.0 |

| Subjective appraisal of distress | 70.0 | 27.19 | 2 | 001.0 |

| Distress alleviation | 83.0 | 32.10 | 2 | 006.0 |

Table 13 presents the results of the repeated measures ANOVA. The within-subject effect of time was statistically significant for all variables: Total distress tolerance score (F = 175.56, P < 0.01), distress tolerance (F = 211.63, P < 0.01), absorption of negative emotions (F = 193.18, P < 0.01), subjective appraisal of distress (F = 142.24, P < 0.01), and distress alleviation (F = 149.95, P < 0.01), indicating significant changes across the three measurement stages (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up). The time × group interaction was also significant for all variables: Total distress tolerance score (F = 46.58, P < 0.01), distress tolerance (F = 52.08, P < 0.01), absorption of negative emotions (F = 46.10, P < 0.01), subjective appraisal of distress (F = 45.69, P < 0.01), and distress alleviation (F = 37.39, P < 0.01).

| Variables | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total distress tolerance | ||||||

| Between-subjects | ||||||

| Time | 81.7765 | 63.1 | 29.4740 | 56.175 | 001.0 | 75.0 |

| Time × group | 48.4121 | 27.3 | 88.1257 | 58.46 | 001.0 | 62.0 |

| Within-subjects | ||||||

| Group | 14.7938 | 2 | 07.3969 | 03.50 | 001.0 | 63.0 |

| Distress tolerance | ||||||

| Between-subjects | ||||||

| Time | 93.580 | 79.1 | 58.323 | 63.211 | 001.0 | 78.0 |

| Time × group | 93.285 | 59.3 | 63.79 | 08.52 | 001.0 | 64.0 |

| Within-subjects | ||||||

| Group | 43.630 | 2 | 21.315 | 25.66 | 001.0 | 69.0 |

| Absorption of negative emotions | ||||||

| Between-subjects | ||||||

| Time | 43.633 | 60.1 | 71.394 | 18.193 | 001.0 | 77.0 |

| Time × group | 33.302 | 21.3 | 19.94 | 10.46 | 001.0 | 61.0 |

| Within-subjects | ||||||

| Group | 63.627 | 2 | 81.313 | 57.52 | 001.0 | 64.0 |

| Subjective appraisal of distress | ||||||

| Between-subjects | ||||||

| Time | 67.509 | 54.1 | 03.329 | 24.142 | 001.0 | 71.0 |

| Time × group | 42.327 | 09.3 | 68.105 | 69.45 | 001.0 | 61.0 |

| Within-subjects | ||||||

| Group | 14.576 | 2 | 07.289 | 18.38 | 001.0 | 57.0 |

| Distress relief | ||||||

| Between-subjects | ||||||

| Time | 91.537 | 71.1 | 23.314 | 95.149 | 001.0 | 72.0 |

| Time × group | 28.268 | 42.3 | 36.78 | 39.37 | 001.0 | 56.0 |

| Within-subjects | ||||||

| Group | 17.512 | 2 | 08.256 | 40.28 | 001.0 | 49.0 |

Abbreviations: SS, sum of squares; MS, mean square.

Furthermore, the between-subject effect of group reached statistical significance for total distress tolerance score (F = 50.03, P < 0.01), distress tolerance (F = 66.25, P < 0.01), absorption of negative emotions (F = 52.57, P < 0.01), subjective appraisal of distress (F = 38.18, P < 0.01), and distress alleviation (F = 28.40, P < 0.01), indicating significant differences between the experimental and control groups. These results suggest that both ST and CFT significantly increased distress tolerance and its components in patients with HIV, with improvements maintained at the post-test and three-month follow-up stages.

Table 14 presents the results of the Bonferroni post-hoc test for pairwise comparisons across measurement stages for distress tolerance and its subcomponents. The findings indicate a statistically significant increase from pre-test to both post-test and follow-up for all variables, with no significant differences between post-test and follow-up stages.

| Variables | Mean Difference | Standard Error | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total distress tolerance | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | -98.13 a | 76.0 | 001.0 |

| Follow-up | -88.13 a | 04.1 | 001.0 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | 231.0 | 73.0 | 1 |

| Distress tolerance | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | -96.3 a | 17.0 | 001.0 |

| Follow-up | -63.3 a | 22.0 | 001.0 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | 33.0 | 23.0 | 492.0 |

| Absorption of negative emotions | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | -08.4 a | 172.0 | 001.0 |

| Follow-up | -86.3 a | 27.0 | 001.0 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | 217.0 | 24.0 | 1 |

| Subjective appraisal of distress | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | -65.3 a | 182.0 | 001.0 |

| Follow-up | -48.3 a | 298.0 | 001.0 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | 167.0 | 239.0 | 1 |

| Distress alleviation | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | -70.3 a | 18.0 | 001.0 |

| Follow-up | -63.3 a | 26.0 | 001.0 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | 067.0 | 27.0 | 1 |

| Total distress tolerance | |||

| ST | |||

| CFT | 11.8 a | 62.1 | 001.0 |

| Control | 15.8 a | 62.1 | 001.0 |

| CFT | |||

| Control | 26.16 a | 62.1 | 001.0 |

| Distress tolerance | |||

| ST | |||

| CFT | 36.2 a | 39.0 | 001.0 |

| Control | 21.2 a | 39.0 | 001.0 |

| CFT | |||

| Control | 58.4 a | 39.0 | 001.0 |

| Absorption of negative emotions | |||

| ST | |||

| CFT | 63.1 a | 44.0 | 001.0 |

| Control | 88.2 a | 44.0 | 001.0 |

| CFT | |||

| Control | 51.4 a | 44.0 | 001.0 |

| Subjective appraisal of distress | |||

| ST | |||

| CFT | 98.1 a | 50.0 | 001.0 |

| Control | 4.2 a | 50.0 | 001.0 |

| CFT | |||

| Control | 38.4 a | 50.0 | 001.0 |

| Distress alleviation | |||

| ST | |||

| CFT | 40.1 a | 54.0 | 040.0 |

| Control | 66.2 a | 54.0 | 001.0 |

| CFT | |||

| Control | 06.4 a | 54.0 | 001.0 |

Abbreviations: ST, schema therapy; CFT, compassion-focused therapy.

a A statistically significant mean difference based on Bonferroni- adjusted post- hoc comparisons (P < 0.05).

Additionally, the table shows the post-hoc comparisons between the two intervention groups. Across all variables, the mean differences between the CFT group and the control group were greater than those between the ST group and the control group, suggesting that CFT had a stronger effect on increasing distress tolerance and its subcomponents in patients with HIV.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of ST and CFT on self-blame and distress tolerance in PLWH. The findings indicate that both interventions were significantly more effective than the control condition; however, CFT demonstrated superior effects in reducing self-blame and increasing distress tolerance. These improvements were maintained at the three-month follow-up, suggesting durable therapeutic benefits.

The finding that CFT is highly effective in reducing self-blame is consistent with the theoretical foundations of the model and with prior research in other populations. The CFT targets the psychological mechanisms underlying self-criticism by training individuals to activate their innate capacity for compassion and self-soothing. For PLWH, who may internalize societal stigma and self-blame, CFT offers strategies to cultivate a kinder, more supportive internal relationship. Its greater effectiveness compared to ST may be attributed to this direct focus on transforming the functional impact of self-blame, rather than primarily challenging the cognitive content of maladaptive beliefs.

Both ST and CFT were also effective in enhancing distress tolerance, with CFT showing a greater effect. This may be explained by CFT’s emphasis on balancing the brain’s emotional regulation systems. By cultivating a compassionate mind, individuals learn to engage their self-soothing system in response to distress, thereby increasing their capacity to tolerate and manage painful emotions without becoming overwhelmed. These results align with evidence suggesting that self-compassion functions as a potent emotional regulation strategy.

The CFT aims to reduce clinical symptoms and self-blame by altering the way individuals respond to their emotions and thoughts (21). Specifically, this approach teaches patients to be kind and forgiving toward themselves, fostering empathy, warmth, and sensitivity in all aspects of their lives, including their actions and emotions. Patients learn to accept that failure is an inevitable part of life, shared by all humans, and that life is inherently imperfect and marked by flaws (27). For PLWH, CFT helps them stop avoiding or suppressing painful emotions and instead recognize, understand, and approach these experiences with empathy and non-judgment, thereby cultivating a compassionate self-attitude. To achieve this, patients are provided with effective strategies they can apply during difficult experiences, rather than relying on habitual, often maladaptive, coping mechanisms.

The ST, in contrast, emphasizes the identification and modification of maladaptive schemas to achieve psychological improvement. Self-blame is a key risk factor associated with the development and maintenance of maladaptive beliefs. Through ST interventions, PLWH become aware of the harsh, destructive, and self-blaming nature of their self-critical thoughts. They also learn to differentiate between themselves and the criticisms directed at their own behavior (28).

In ST, self-blame is strongly linked to feelings of inadequacy, inferiority, and worthlessness, and is highly sensitive to criticism and blame from others. These feelings are often accompanied by shame and insecurity, particularly in social contexts, and stem from a deeply negative self-image (29). Patients who participated in ST interventions became aware of the damaging nature of their self-critical and self-blaming thoughts through ST techniques (30).

Both ST and CFT were effective in increasing distress tolerance; however, CFT showed a greater effect. This may be explained by its emphasis on balancing the brain’s emotional regulation systems. By cultivating a compassionate mind, individuals engage their self-soothing system in response to distress, increasing their capacity to manage painful emotions without becoming overwhelmed. These findings align with previous research suggesting that self-compassion functions as a potent emotional regulation strategy (31).

Previous research has demonstrated that CFT significantly increases distress tolerance and improves interpersonal beliefs, such as in women with substance-dependent spouses (32). Given the psychological burden associated with living with HIV, reductions in distress tolerance among PLWH are not unexpected. The effectiveness of CFT in enhancing distress tolerance and its components may be explained by its ability to increase oxytocin secretion, which in turn activates the brain’s soothing and safeness system (33).

Self-compassion plays a central role in emotional regulation by enabling individuals to face difficult emotions with acceptance and understanding, thereby improving their capacity to manage distress. Consequently, PLWH who cultivate greater self-compassion are better equipped to manage negative emotions, which contributes to improvements in distress tolerance.

Developing self-compassion also requires mindful awareness of one’s emotional experiences. Instead of avoiding or suppressing painful feelings, individuals learn to approach them with warmth, kindness, acceptance, and a sense of shared humanity (34). By balancing emotional regulation systems, CFT functions as an effective strategy for managing emotions. It helps individuals engage their self-soothing system in response to perceived threats, thereby improving their ability to cope with life’s stressors and painful events. For instance, when confronting challenges such as illness, patients can enhance their self-compassion through structured interventions, cultivating a compassionate mind and deepening their understanding of personal suffering rather than avoiding it (23).

Furthermore, PLWH learn that self-compassionate evaluations are not solely contingent on behavioral outcomes. Regardless of whether life events are positive or negative, individuals maintain a compassionate acceptance toward themselves. This approach fosters higher self-esteem and a deeper understanding that failure and imperfection are inherent aspects of the human experience (35). The application of self-soothing techniques in daily life also plays a crucial role in managing distress.

Evidence indicates that group ST can significantly enhance distress tolerance compared to control conditions (36). In the context of the current study, ST targets negative cognitive patterns, maladaptive schemas, and emotional reactivity, helping patients develop new ways of interpreting experiences. This process reduces emotional dysregulation and contributes to improvements in distress tolerance among PLWH.

The ST skills, through cognitive restructuring and the replacement of maladaptive emotional management strategies, help reduce chronic interpersonal difficulties and emotional instability. This process enhances both emotional and cognitive regulation. Improved cognitive regulation supports mental and emotional processing, thereby strengthening coping capacity and distress tolerance (37). Moreover, ST enables individuals to employ healthy and effective coping strategies. These adaptive mechanisms increase psychological flexibility and problem-solving abilities, contributing to greater distress tolerance. As problem-solving skills improve, individuals are less likely to avoid challenges and more likely to confront and overcome them effectively (38).

The clinical significance of these findings is noteworthy. The magnitude of change observed, particularly in the CFT group, suggests a shift from clinically significant levels of self-blame and low distress tolerance to scores within a more functional, non-clinical range. For PLWH, enhanced distress tolerance may lead to better management of treatment-related side effects and improved interpersonal relationships. Likewise, reduced self-blame can alleviate depression and anxiety, fostering a greater sense of hope and self-worth.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this RCT indicate that both ST and CFT are effective interventions for reducing self-blame and enhancing distress tolerance across groups and time points among PLWH. However, CFT demonstrated significantly greater effectiveness on both outcomes. These therapies support patients in regulating emotions and modifying maladaptive thought patterns, enabling the adoption of healthier cognitive perspectives and more adaptive coping strategies. Given its superior impact, CFT may be particularly well-suited for addressing the shame and self-criticism commonly experienced by PLWH, offering a valuable approach for improving psychological well-being in this population.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the three-month follow-up period is relatively short; longer-term assessments are needed to determine the sustainability of therapeutic gains. Second, participants were recruited from a single center in Tehran, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Third, several potential confounding variables such as adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), socioeconomic status, psychiatric comorbidities, or duration of HIV diagnosis were not controlled. Fourth, although the therapist was trained and supervised, individual therapist skill may have influenced outcomes. Finally, while the sample size was adequately powered, it was modest; future studies with larger samples are warranted.