1. Background

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) comprises a group of rare, monogenic disorders characterized by a block in T lymphocyte development, leading to life-threatening infections in early infancy (1, 2). Affected infants are often affected by opportunistic fungal, bacterial, or viral infections within the first months of life and, without immune reconstitution, succumb within the first year (2). Severe combined immunodeficiency is considered a pediatric medical emergency, given that timely diagnosis and intervention are critical for survival. The estimated incidence of SCID is approximately 1 in 50,000 - 100,000 live births. Particularly, in regions with high rates of consanguinity, the incidence can be markedly higher, due to the increased prevalence of autosomal recessive forms of SCID. However, in many developing countries lacking newborn screening programs, SCID cases are frequently underdiagnosed or diagnosed late. Indeed, while several countries have implemented routine newborn screening for SCID using T-cell receptor excision circle (TREC) assays, most low-income settings still rely on clinical suspicion that results in delays until severe infections manifest.

Severe combined immunodeficiency is genetically heterogeneous, with mutations in at least 20 distinct genes, though recent classifications consolidate these into 18 recognized genetic causes known to cause a SCID phenotype. These defects span various molecular pathways, including impaired V(D)J recombination, cytokine signaling abnormalities like IL2RG, JAK3, IL7R, and metabolic defects (3-5). Among these, X-linked SCID caused by mutations in the IL2RG gene, encoding the interleukin-2 receptor common gamma chain, γc, is the single most common subtype. A historical cohort study indicated that IL2RG mutations account for approximately 40 - 50% of all SCID cases (6), making this the most prevalent form of the disease. Accordingly, in an analysis of 108 SCID infants, 49 had X-linked IL2RG mutations, far exceeding any other genetic subtype (6). IL2RG is located on Xq13.1 and encodes the shared γc subunit of at least six cytokine receptors, including IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21 (7). This common γ-chain is critical for lymphocyte development and function. Consequently, IL2RG mutations abrogate multiple cytokine signaling pathways, leading to a characteristic SCID immunophenotype of absent T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells with non-functional B cells (T⁻B⁺NK⁻ SCID) (7). Basically, X-linked SCID is a disease of defective interleukin signaling, explaining its severe combined loss of cellular immunity. Especially, autosomal recessive forms like JAK3 deficiency phenocopy X-linked SCID because JAK3 is the kinase that associates with γc, underscoring the central role of the IL2RG signaling axis in normal immune development.

Therapeutic options for SCID are available in the form of immune reconstitution, most commonly through hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Outcomes for HSCT in SCID have improved dramatically over time, and survival rates now exceed 90% for infants who receive a transplant from a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical sibling donor in the first few months of life (8). Even with partially matched donors, early transplantation (before the onset of irreversible infections) significantly enhances survival, highlighting the importance of prompt diagnosis. Experimental gene therapy has also shown success in certain SCID subsets (including IL2RG deficiency), further expanding treatment options (1). The key to these favorable outcomes is early identification of affected infants, ideally at birth, before infections occur (8, 9). This has driven the adoption of newborn screening for SCID in many high-income countries, using the TREC assay to detect T-cell lymphopenia in dried blood spots (10). T-cell receptor excision circle screening is highly sensitive for SCID and related T-cell defects, allowing presymptomatic diagnosis. However, newborn screening by itself does not reveal the underlying genetic cause – it can flag an infant as likely SCID, but cannot distinguish IL2RG mutation from other etiologies. Moreover, some atypical or "leaky" SCID cases (with milder T-cell deficits) might initially pass newborn screening, only to present later with immunodeficiency (11). These limitations underscore the need for comprehensive genetic diagnostics following an abnormal screen or in patients with clinical SCID features in settings without screening.

Advances in genomic technology, particularly whole exome sequencing (WES), have revolutionized the diagnostic approach to SCID and other primary immunodeficiencies (12). This has proven invaluable for confirming the diagnosis and guiding therapy, especially in cases with atypical presentation or in families where the specific genetic defect is not evident. With such methods, over 90% of infants with SCID in contemporary North American cohorts are genetically characterized (13). Furthermore, genetic sequencing is crucial for distinguishing between different genetic forms of SCID that may present with similar clinical and immunologic features, such as RAG1/2 mutations causing Omenn syndrome versus other SCID forms (2). Knowing the exact molecular defect has practical implications. It informs family counseling and can influence treatment decisions, such as eligibility for gene therapy trials or the urgency and conditioning regimen for HSCT (1, 8). That said, the widespread use of WES has also introduced new challenges, such as the interpretation of variants of uncertain significance (VUS). In some SCID cases, WES uncovers novel missense changes whose functional impact is not immediately clear, necessitating supplementary studies. As a finding, functional assays have been used to confirm the pathogenicity of ambiguous RAG1 variants discovered by sequencing as a definitive diagnosis.

Diagnosing and managing SCID poses particular challenges in resource-limited settings. Many low- and middle-income countries lack routine newborn screening programs for SCID, and awareness among clinicians may be limited, leading to missed or delayed diagnoses. Infants in these settings often present only after developing severe infections or failure to thrive, at which point opportunistic pathogens like Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine strain, given as newborn tuberculosis prophylaxis in many countries, may have already caused disseminated disease. The delay not only increases immediate mortality risk but can also compromise the success of curative therapy since active infections and organ damage at transplant are associated with worse outcomes. A further obstacle is the limited availability of advanced diagnostic tools. In the absence of in-country genomic facilities, confirming a suspected SCID diagnosis genetically may rely on sending samples abroad or not be done at all, leaving the genetic subtype unknown. This lack of definitive diagnosis can impede optimal treatment; distinguishing IL2RG deficiency (X-linked) has implications for family screening and donor search, and identifying ADA deficiency might allow enzyme replacement therapy as a bridge to transplant. Moreover, access to HSCT itself is variable in resource-limited regions; even when a genetic diagnosis is made, specialized transplant centers and suitable donors may not be readily accessible. Paradoxically, the regions with higher SCID incidence due to consanguinity are often those with the scarcest resources for early detection and treatment. This disparity highlights an urgent need for international collaboration and capacity-building, training healthcare providers to recognize SCID, and implementing cost-effective genetic testing (such as targeted sequencing panels or exome sequencing via regional centers) to facilitate prompt diagnosis.

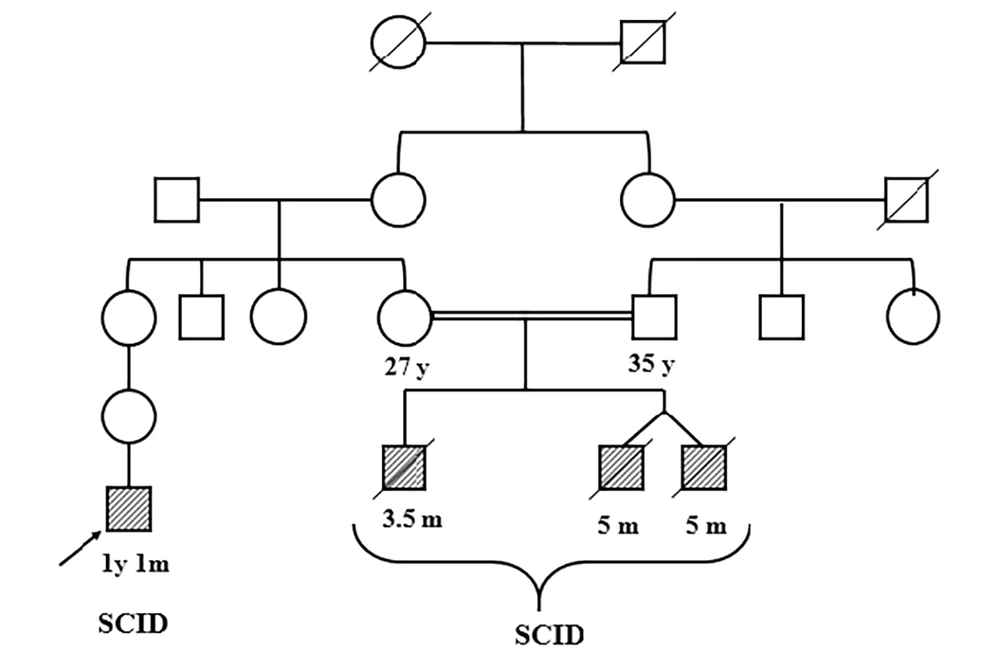

Within this context, IL2RG mutations remain a focal point because of their relative frequency and clear therapeutic implications. X-linked SCID cases can be identified by family history or by carrier testing in mothers once a mutation is known, which emphasizes the value of molecular diagnosis. Published reports from the Middle East and Asia have begun to catalog the spectrum of IL2RG mutations in their SCID populations. However, data on SCID in certain regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia, remain very scarce. Even in countries like Iran, where consanguinity is observed and autosomal recessive SCID (e.g., RAG deficiencies) might be expected to predominate, X-linked IL2RG mutations still account for a substantial fraction of cases. Every new case study adds to the collective knowledge needed to improve outcomes. Accordingly, the present study reports SCID in monozygotic twins, a rare but especially informative scenario, providing a controlled look at genotype-phenotype correlation and the impact of environmental factors on disease course. Such findings can improve our understanding of SCID pathogenesis and inheritance patterns.

In this study, we present the case of monozygotic twin infants from a resource-limited setting who were diagnosed with SCID due to a pathogenic IL2RG mutation, identified through WES. We describe the clinical presentation (including severe recurrent infections and BCGiosis), the immunological findings, and the genetic analysis confirming an X-linked IL2RG variant, which was verified by family segregation. This report highlights the utility of WES in reaching a definitive diagnosis in the absence of newborn screening and shows the challenges of managing SCID in a setting with limited resources. By integrating genomic data with clinical and immunological evaluation, the critical role of IL2RG in immune development is highlighted, and the need for broader implementation of genomic newborn screening and early referral for curative therapy is advocated. Also, the findings contribute to the growing global registry of SCID mutations and support efforts to ensure that life-saving interventions for SCID, like timely HSCT or gene therapy, become accessible to all patients, regardless of geographic location or resource availability.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Participants and Sample Collection

This study involved monozygotic twin male infants (5 months old) presenting with clinical features of SCID, including recurrent bacterial infections and failure to thrive. They had a history of disseminated BCG infection following newborn vaccination. The infants were referred to a specialized immunology-genetics clinic in Iran after SCID was suspected. Peripheral blood samples (approximately 2.5 mL) were collected in EDTA tubes from each twin and their parents (after informed consent). Genomic DNA was extracted from leukocytes using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality and concentration were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to ensure high-molecular-weight DNA suitable for sequencing.

2.2. Whole Exome Sequencing

Whole exome sequencing was performed on the proband. Exome capture was conducted using the SureSelect Human All Exon V7 kit (Agilent Technologies, USA). Sequencing was carried out on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Macrogen, Korea) to generate 150 bp paired-end reads. The sequencing data achieved a mean coverage of approximately 200X, with > 95% of the target exonic regions covered at a depth of at least 20X.

Bioinformatic analysis was performed as follows: Raw sequencing reads were aligned to the GRCh38/hg38 reference genome using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA). Variant calling was conducted using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) best practices pipeline. Variant annotation and prioritization were performed using CLC Genomics Workbench v7.7 (QIAGEN) and cross-referenced with public databases including gnomAD, dbSNP, and ClinVar.

Variant filtering was applied to identify the causative mutation. We focused on rare, protein-altering variants (missense, nonsense, frameshift, splice-site) with a population frequency of < 0.1% in gnomAD. Given the male sex of the patients and the X-linked inheritance pattern suggested by the family history (no male-to-male transmission), we prioritized hemizygous variants on the X chromosome. The filtered list was further scrutinized for genes with known roles in immune function, particularly those associated with SCID.

2.3. PCR and Sanger Sequencing

Candidate variant validation and family segregation analysis were carried out by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing of the IL2RG gene. Custom primers flanking the putative mutation site were designed (Primer3Plus/NCBI Primer-BLAST) with the following sequences: IL2RG exon 5 forward 5′-TACTCTTCCTGATACCAGATAG-3′ and reverse 5′-CTACTCTAACACACCCCAAC-3′. PCR was performed in a 40 µL reaction containing 20 - 50 ng genomic DNA, 0.8 µM of each primer, 2.5 µL of 10× PCR buffer, 1 µL of each dNTP (10 mM), 2 µL of MgCl₂ (25 mM), 0.1 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/µL), and nuclease-free water to volume. Thermocycling conditions were: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; followed by 36 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were confirmed on a 1.5% agarose gel and then purified for Sanger sequencing (performed by Macrogen, Korea). Chromatogram analysis (using CLC Workbench) enabled confirmation of the WES-identified variant in the twins and the determination of parental carrier status.

2.4. Clinical and Immunological Assessments

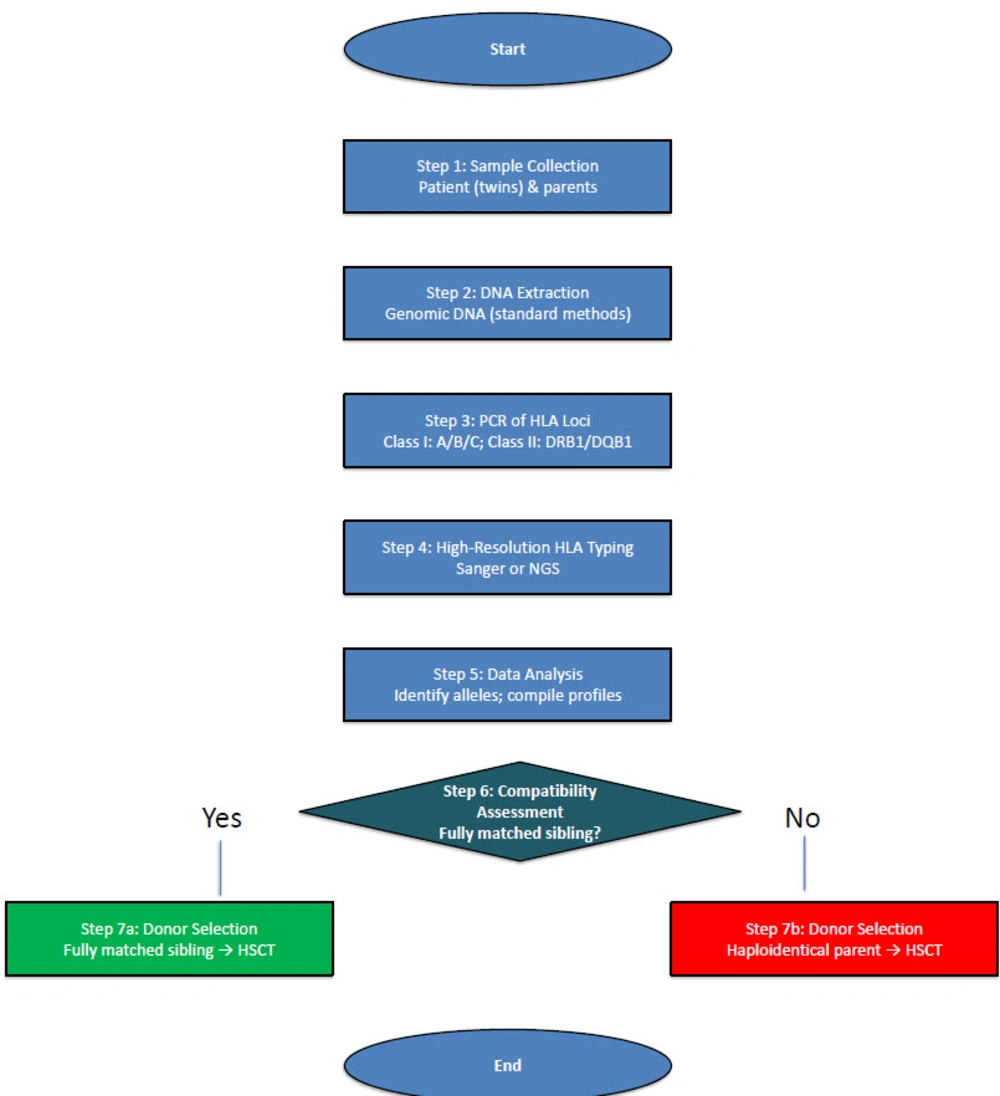

Comprehensive clinical evaluations were conducted. Key features recorded included the frequency and type of infections, such as pneumonia and sepsis with Staphylococcus haemolyticus, vaccination history (notably the BCG-related complications), and growth parameters. Laboratory tests revealed profound lymphopenia on complete blood counts (absolute lymphocyte count < 300 cells/µL, far below age-matched normals). Flow cytometry was not available, but immunophenotyping was inferred from TREC and clinical data. In preparation for potential treatment, HLA typing was performed for the twins and their parents at HLA class I (A, B, C) and class II (DRB1, DQB1) loci using high-resolution sequence-based methods. Human leukocyte antigen results were used to evaluate the feasibility of HSCT from family donors.

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Analysis

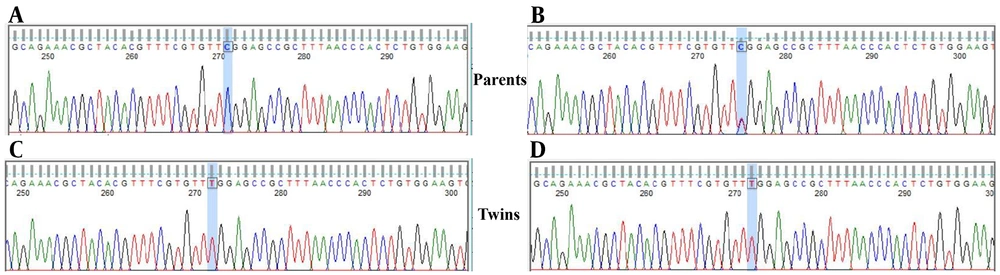

Whole exome sequencing of the proband identified a hemizygous variant in IL2RG, located on chromosome Xq13.1 that perfectly matched the clinical suspicion of X-linked SCID. The variant was a single nucleotide change c.670C>T in the IL2RG coding sequence, predicting a missense substitution p.Arg224Trp in the common gamma chain protein. This was the only rare, protein-altering variant on the X chromosome that could explain the phenotype. The variant was absent from population databases (gnomAD frequency 0.0%), and in silico predictors (PolyPhen-2, SIFT) indicated it is deleterious. Table 1 summarizes the genomic findings. Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of the IL2RG c.670C>T mutation in both twins, and additionally showed that their mother is heterozygous for this variant (carrier), while the father’s sequence is wild-type. These results are consistent with X-linked recessive inheritance of the disease-causing mutation. The IL2RG p.Arg224Trp variant has previously been classified as pathogenic (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000255579.1/) in X-SCID patients and was not found in healthy individuals (Figure 1).

| Gene | Genomic Coordinate (GRCh38) | Nucleotide Change | Amino Acid Change | Zygosity | Predicted Pathogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL2RG | X:70, 329, 165 | c.670C>T | p.Arg224Trp | Hemizygous (male) | Damaging (PolyPhen-2, SIFT) |

a No other candidate variants explaining the immunodeficiency were found on autosomal genes (e.g., RAG1/2, JAK3, ADA), consistent with IL2RG being the sole causative mutation.

Sanger sequencing chromatograms demonstrating the IL2RG c.670C>T (p.Arg224Trp) variant in the family; the top panel shows the father’s wild-type sequence (A), the middle panel depicts the mother’s heterozygous state (B), and the bottom panels (C and D) confirm the hemizygous mutation in both monozygotic twins. The arrow highlights the nucleotide substitution (C→T), which leads to the pathogenic p.Arg224Trp change associated with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID).

3.2. Human Leukocyte Antigen Typing and Familial Segregation

Family HLA typing revealed only partial haplotype matches between the twins and their parents (Figure 2), and no fully matched sibling donor was available (the twins have no other siblings). Table 2 shows the HLA alleles for the proband, mother, and father. The twins shared one HLA haplotype with the mother and one with the father, as expected for an X-linked condition inherited from a carrier mother. For example, the proband is HLA-DRB101:01/01:01 (inherited one DRB101:01 allele from each parent) and HLA-DQB1*05:01/05:01 (one DQB105:01 from each parent), indicating haploidentical matches with both parents. The mother and father each share half of their HLA alleles with the affected infants, but neither parent is a full HLA match at all loci. These results indicate that an alternative donor source (such as a haploidentical parental transplant with T-cell depletion or an unrelated donor) would be required for HSCT, as no HLA-identical sibling donor exists.

Abbreviation: HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

a The proband’s human leukocyte antigen alleles (HLA-A) are compared to those of the mother and father. The proband’s HLA-A alleles (likely A11 and A30) each match one parent (A11 from father, A30 from mother), but there is no overlap between parental A alleles; hence, no exact HLA-A match is shared by both parents.

b No exact match.

c Homozygous.

3.3. Clinical Findings

Both twins manifested severe clinical symptoms of immunodeficiency early in life (Table 3). They suffered recurrent, hard-to-treat infections. Notably, each developed pneumonia and sepsis with organisms such as S. haemolyticus, and both had disseminated BCG infection (BCG-osis) following administration of the live attenuated BCG vaccine at birth. The disseminated mycobacterial infection was confirmed by finding granulomas on biopsy and acid-fast bacilli in a bone marrow aspirate. Immunologically, the infants were profoundly lymphopenic: Total lymphocyte counts were < 300 cells/µL (normal for age is > 4,000/µL). There was an absence of functional T-cells, CD3+ lymphocytes were extremely low, and NK cells were absent, whereas B cells were present with a T⁻B⁺NK⁻ phenotype. However, the B cells were non-functional, evidenced by extremely low immunoglobulin levels and lack of specific antibody production despite infection, consistent with the need for T-cell help. The TREC assay was undetectable in both patients, indicating virtually no new T-cells emerging from the thymus. These findings confirmed a diagnosis of X-linked SCID with T⁻B⁺NK⁻ subtype. Both infants required isolation and prophylactic antimicrobial interventions while a definitive therapy was planned. Diagram outlining the high-resolution HLA typing workflow used to assess donor compatibility. Figure 3 displays the HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 allele distributions among the proband and his parents, emphasizing the partial haplotype matches critical for selecting a suitable donor for HSCT.

| Parameter | Twin 1 | Twin 2 | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presenting Age | 5 months | 5 months | - |

| Major infections | Recurrent pneumonia, sepsis (Staphylococcus haemolyticus), disseminated BCG | Recurrent pneumonia, sepsis (S. haemolyticus), disseminated BCG | - |

| BCG complications | Disseminated BCG (BCG-osis) confirmed by granulomas on biopsy and AFB in bone marrow | Disseminated BCG (BCG-osis) | - |

| Growth | Failure to thrive | Failure to thrive | - |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/µL) | < 300 | < 300 | > 4,000 |

| TREC assay | Undetectable | Undetectable | Detectable |

| Immunophenotype | T⁻B⁺NK⁻ (inferred from lymphopenia, absent TRECs, and clinical profile) | T⁻B⁺NK⁻ (inferred) | - |

| Immunoglobulins | Extremely low levels | Extremely low levels | Age-appropriate |

| Genetic finding | IL2RG: c.670C>T, p.Arg224Trp (hemizygous) | IL2RG: c.670C>T, p.Arg224Trp (hemizygous) | - |

| HLA match for HSCT | Partial haplotype match with both parents; No fully matched sibling donor | Partial haplotype match with both parents; No fully matched sibling donor | - |

Abbreviations: BCG, bacille Calmette-Guerin; AFB, acid-fast bacilli; NK, natural killer; TREC, T-cell receptor excision circle; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

4. Discussion

This report provides a detailed genetic and clinical investigation of X-SCID in identical twin brothers. As a result, a hemizygous c.670C>T (p.Arg224Trp) mutation was identified in IL2RG as the cause of their condition. The IL2RG gene encodes the common γc, a crucial subunit shared by multiple cytokine receptors, including IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21 that regulate lymphocyte development (14). Disruption of the common γc due to IL2RG mutations impairs signaling through all these cytokines, arresting the maturation of T-cells and NK cells, while B cells develop but cannot function properly without T-cell help. This immunologic mechanism explains the classic SCID phenotype observed in the patients, and aligns with the fact that mutations in IL2RG are the single most common cause of SCID globally (15). Large cohort studies have shown that X-linked IL2RG deficiency accounts for roughly 40 - 50% of all SCID cases (15).

The specific IL2RG variant in these twins (p.Arg224Trp) is a known pathogenic mutation associated with X-SCID (15-20). It lies in the extracellular domain of the γc protein, and the substitution of a positively charged arginine with a bulky tryptophan is predicted to disrupt the receptor’s structure and its interaction with interleukins. Indeed, this variant has been reported in multiple unrelated SCID patients and is not found in healthy population databases (15-17). These findings are consistent with previous reports that IL2RG missense mutations abolish common γc receptor function, leading to the absence of T and NK cells and nonfunctional B cells (14). By confirming the mutation in both twins and the carrier state in their mother, genetic evidence of X-linked inheritance was provided, which is valuable information for family counseling, such as the risk to future male children.

Although functional assays were not performed in this study, the pathogenicity of the p.Arg224Trp variant is well-established in the literature as mentioned above. This specific mutation has been previously reported in multiple unrelated X-SCID patients and is classified as pathogenic in the ClinVar database (Accession: RCV000255579.1). Functional studies cited in these reports (15-20) demonstrate that the p.Arg224Trp substitution disrupts the interleukin-2 receptor common gamma chain (γc) function, abrogating cytokine signaling essential for T and NK cell development (15, 16). This provides strong evidence that the p.Arg224Trp variant is the definitive cause of SCID in these twins.

Clinically, the twins’ presentation was characteristic of SCID. They experienced life-threatening infections within months of birth and did not respond normally to vaccines, developing disseminated disease from an attenuated vaccine strain. If untreated, infants with SCID typically succumb to severe infections within the first year of life (3, 21, 22), reflecting the absolute dependence of the adaptive immune system on functional T-cells. In these twins, the absence of TRECs was a key laboratory finding. T-cell receptor excision circles are circular DNA fragments excised during T-cell receptor gene rearrangement in the thymus, and they serve as a biomarker for recent thymic emigrants (10, 21). The twins’ undetectable TREC levels indicate almost complete failure of thymic T-cell production, consistent with X-SCID. These results mirror what is seen in newborn screening programs for SCID: Babies with absent or extremely low TRECs are flagged for urgent evaluation and often found to have SCID (21, 23). Thanks to newborn screening, many SCID cases in developed programs are now identified at birth before infections occur (24). Unfortunately, no such screening was in place for our patients at the time of this study. Their diagnosis was made after clinical illness had begun, illustrating the pediatric emergency nature of SCID – early diagnosis is crucial to prevent fatal infections.

The definitive treatment for SCID is allogeneic HSCT, which can reconstitute a functional immune system in the patient (1). Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation outcomes are vastly improved when performed in the first months of life, ideally before the infant has acquired severe infections (25). Historical data and recent multicenter studies concur that infants transplanted at ≤ 3.5 months of age have survival rates > 90% (25, 26). In the case of the twins, the HLA typing results indicated that neither had an HLA-identical sibling donor. The best available options would likely be a haploidentical parental transplant (using the father or mother as a donor, with T-cell depletion to prevent graft-versus-host disease) or searching for a well-matched, unrelated donor. It is well documented that any delay in performing HSCT for SCID correlates with worse survival, largely due to infections acquired while waiting for a transplant. Therefore, upon genetic confirmation of SCID, an expeditious referral for HSCT is recommended even if only a haploidentical donor is available, as outcomes with parental donors can be life-saving when done early in life (25, 26).

The present study also highlights the disparities in healthcare infrastructure. Regions without newborn screening programs or easy access to transplant centers face significant challenges in managing SCID. In countries like Iran, where our patients reside, SCID diagnoses often rely on clinical recognition of infections and failure to thrive, which may occur late in the disease course. This delay leads to higher infection-related morbidity and mortality. Moreover, areas with a high rate of consanguineous marriages see a greater prevalence of autosomal recessive forms of SCID and other primary immunodeficiencies, further increasing the burden of undiagnosed cases. These findings emphasize the urgent need for implementing population-wide SCID newborn screening in such regions. Even a simple TREC-based DNA test on Guthrie cards can identify SCID in the first days of life, enabling prompt protective measures and timely curative therapy (24). Alongside screening, genetic counseling and carrier testing in families with known X-SCID is essential. In the case of the twins, identification of the carrier mother allows informed reproductive choices and early testing of future male infants in the extended family.

Another important aspect of this case is the demonstration of how genomic technologies complement immunological tests for a precise diagnosis. Traditional diagnostics for suspected SCID include lymphocyte phenotyping and functional assays like mitogen proliferation tests, which can confirm an immunodeficiency but not its genetic cause. Here, WES was decisive in pinpointing IL2RG as the mutated gene, which not only clinched the diagnosis of X-SCID but also guided the family workup, identifying the carrier mother. The power of WES to reveal the molecular basis of rare diseases has revolutionized medical genetics (12). It is especially valuable in genetically heterogeneous conditions like SCID, which can result from mutations in over a dozen different genes (1). Recent studies from Iran and other countries with limited resources have shown that applying WES can significantly improve the diagnostic yield for patients with primary immunodeficiencies, uncovering mutations that targeted gene panels might miss (4). Our report adds to this body of evidence, illustrating that even in a resource-constrained setting, integrating WES into the diagnostic workflow for infants with severe immune syndromes is feasible and impactful. By identifying a specific genetic defect, we can tailor the management and provide accurate genetic counseling. In cases where WES identifies VUS, further functional studies by measuring cytokine signaling in patient T-cells or targeted gene assays may be needed.

Looking forward, advancements in therapy, such as gene therapy, offer hope to patients with X-SCID. Early trials demonstrated that integrating a correct copy of IL2RG into patient hematopoietic stem cells could reconstitute T-cell immunity, but some patients developed leukemia due to retroviral vector insertion near oncogenes. In recent years, improved vectors, such as self-inactivating lentiviral vectors, have made gene therapy for SCID much safer, and new trials have shown successful immune reconstitution without unexpected cancers (1). In the context of the presented case, gene therapy could be considered, although at present HSCT from a haploidentical donor is the standard approach. Long-term follow-up of SCID patients treated with HSCT or gene therapy is an important need. Issues such as chronic graft-versus-host disease, incomplete immune reconstitution like poor B-cell function requiring lifelong immunoglobulin replacement, or late complications like secondary malignancies need to be monitored in survivor cohorts. Fortunately, outcomes for X-SCID have dramatically improved over the past few decades, with > 90% of infants now surviving if treated early (26). This study of cases with X-SCID contributes to the literature by expanding the known mutation spectrum of IL2RG by adding p.Arg224Trp as a recurrent pathogenic variant and by emphasizing the multi-faceted approach required, from genomics to clinical care, to achieve the best outcomes for SCID patients. Yet, while this study is based on a single family, the detailed investigation of monozygotic twins provides a unique and controlled perspective on the presentation and genetic basis of X-SCID.

4.1. Conclusions

This study highlights the critical importance of early genetic diagnosis in infants with SCID and the life-saving potential of early intervention. The identification of the IL2RG c.670C>T (p.Arg224Trp) mutation in these twins enabled a timely, definitive diagnosis and informed treatment planning. Routine use of WES or genetic panels in any infant suspected of SCID is advocated, especially in the absence of newborn screening. Such approaches allow rapid diagnosis and guide urgent treatment such as HSCT. This research needs additional evidence regarding these cases to emphasize the screening program, but it presents the pathogenic mutation for the first time in Iran. Through early detection and intervention, the historically dismal prognosis of SCID, the “bubble boy” disease, can be converted into excellent long-term survival and quality of life for affected children.