1. Context

Neurobranding, an advanced subset of neuromarketing, applies neuroscientific principles to understand consumer behavior. Unlike traditional methods such as surveys and focus groups, which are often limited by social desirability bias and the inaccuracy of self-reported data (1), electroencephalography (EEG) offers an objective, real-time measure of brain activity. This provides direct insight into the subconscious processes underlying consumer decision-making by capturing immediate neural responses to branding elements like logos and advertisements (2).

In branding, EEG reveals how marketing stimuli elicit distinct emotional and cognitive responses, reflected in differential brain activation. These neural correlates are linked to critical brand perceptions — including trust, familiarity, and desirability — that drive consumer behavior (3). Furthermore, EEG has been used to investigate attention and memory retention, demonstrating how specific branding elements enhance engagement and long-term recall (4).

Despite the steadily increasing number of studies focusing on the role of EEG in branding, there are still some inadequacies in the existing academic literature. For example, current research has focused on either particular sub-groups of consumers or narrowly defined categories of brands, leaving only a small number of studies investigating the relative effects of differing strategies across broader markets (5). Additionally, while EEG captures diverse neural metrics, a consensus on the most meaningful measures for brand impact has yet to be established (6).

Our study addresses these gaps through a specialized synthesis of EEG-based branding research. Unlike the broad marketing mix overview by Bazzani et al. (2), our review offers a focused analysis on branding, and in contrast to Khurana et al.'s extensive survey of neuromarketing methodologies and ethics (5), our manuscript is an application-driven review that incorporates the latest advancements up to 2024.

The findings from this review hold substantial practical implications. As market clutter increases, insights from neurobranding can guide more effective marketing strategies — from logo design to advertising content — by providing scientific evidence of consumer resonance (7). This systematic review thus aims to advance scholarly understanding of EEG in branding while offering actionable recommendations for practitioners (8-14).

Despite the expanding application of EEG in branding research, a dedicated systematic synthesis of its methodologies and findings remains absent. Current reviews often amalgamate EEG with other neuroimaging tools, diluting its unique contributions. This gap is critical, as EEG provides distinct advantages — including millisecond temporal resolution, cost-effectiveness, and portability — making it ideal for capturing subconscious brand processes.

2. Objectives

This systematic review aimed to (1) map the methodologies and analytical approaches employed in EEG-based branding research, and (2) evaluate the evidence regarding EEG’s utility in measuring brand perception, consumer behavior, and marketing effectiveness.

3. Methods

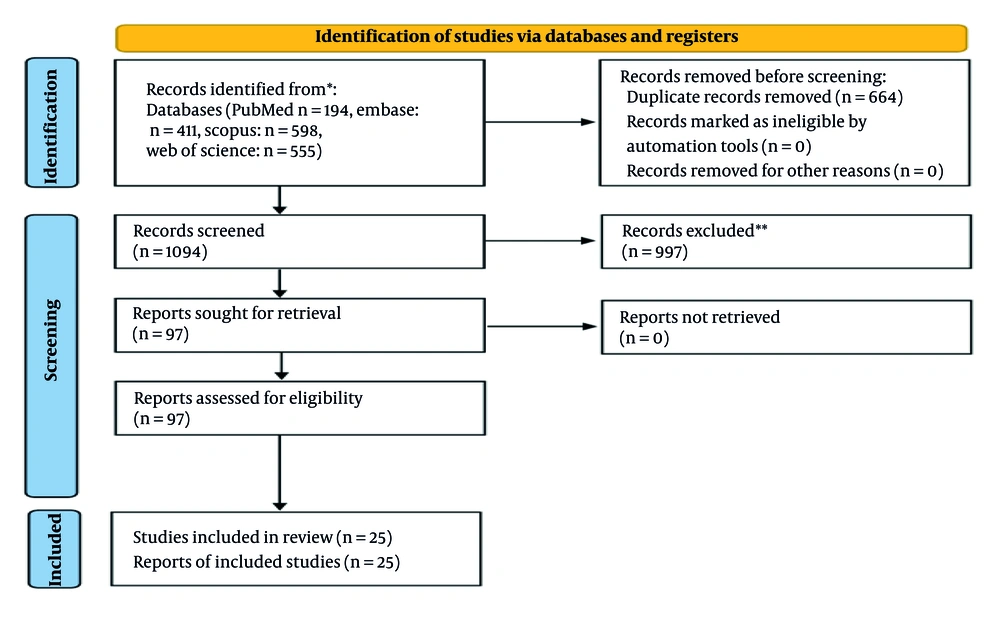

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with established guidelines, drawing upon the PRISMA framework to maintain transparency and replicability in the methodology. The primary objective was to identify and synthesize peer-reviewed research that employed EEG or related neuroimaging techniques to examine cognitive or emotional responses to branding. Studies were deemed eligible if they were published in English in peer-reviewed journals, used EEG or a closely related method in the context of marketing or branding, and explored consumer responses through qualitative and/or quantitative investigations. Non-peer-reviewed publications, grey literature, and unpublished data were excluded, as were studies that did not involve neuroimaging technologies or lacked a clear focus on branding and marketing.

A comprehensive literature search was performed across four electronic databases — Embase, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science — from July 2007 to December 2024. Predefined search terms captured both EEG (for example, “Electroencephalogram”, “EEG”, “electrical encephalogram”, and “brain activity”) and branding or marketing contexts. Searches were tailored to each database and included additional filters for English-language and peer-reviewed sources where appropriate. All resulting records were imported into EndNote software to remove duplicates, and two independent reviewers assessed each title and abstract in light of the eligibility criteria. Any potential discrepancies were reconciled by a third reviewer to ensure consistency in the study selection process. Full-text versions of all articles considered relevant were retrieved and evaluated more thoroughly.

Data extraction was conducted using a standardized form designed to ensure consistency and minimize bias. Extracted information covered study characteristics (including author names, publication year, country of origin, and journal or conference proceedings), methodological details (such as sample size, specific EEG technology, study design, and the branding or marketing setting in which EEG was applied), key findings regarding the relationship between EEG data and consumer responses to branding, and any identified limitations or gaps. Quality assessment followed the QUADAS-2 tool, focusing on the methodological rigor of each study, the adequacy and appropriateness of the sample sizes, the sophistication and reliability of the EEG equipment, and the validity of the branding measures used. These steps collectively ensured a systematic approach to identifying, selecting, and analyzing the studies included in this review.

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection

The systematic search across four databases [Embase (411), PubMed (194), Scopus (598), and Web of Science (555)] initially identified 1,758 records. Following the removal of duplicates, 1,094 unique records underwent title and abstract screening. Of these, 97 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, resulting in 25 studies that met the predefined inclusion criteria for this review. The study selection process followed the PRISMA guidelines and is detailed in the flow diagram (Figure 1). This process was conducted by two independent reviewers, with any discrepancies resolved through consultation with a third reviewer to ensure consistency.

4.2. Summary of Included Studies

A total of 25 articles met the inclusion criteria for this review (15-39). Across these studies, sample sizes ranged from as few as 11 participants (28) to 36 participants (16), with most recruiting university students or young adults. Geographic contexts included Europe (20, 35), Asia (15, 17, 24, 30-33), and other regions. Although all studies focused on consumer behavior from a neuromarketing or consumer neuroscience perspective, their specific aims and methodologies varied substantially.

All included studies employed at least one neurophysiological measure — most commonly EEG and event-related potentials (ERPs) — to capture consumers’ cognitive, emotional, and/or attentional responses. Several articles also incorporated additional methods, such as eye-tracking to assess visual attention (18, 25), galvanic skin response (GSR) or electromyography (EMG) (16, 26, 35), and machine learning approaches (15, 28, 36). Behavioral measures including reaction times, self-reported questionnaires, the implicit association test (IAT), and preference ratings were also used. In most cases, EEG/ERP data were collected while participants viewed, tasted, or evaluated branded stimuli. Common ERP components included N200, N270, N400, P300, LPP, and theta/gamma oscillations, which were linked to conflict processing, semantic integration, attention, and emotional arousal.

4.3. Synthesis of Findings

Research on brand preference and loyalty reveals several important findings. Brown et al. investigated consumer willingness to switch from manufacturer brands to private-label alternatives if price and perceived taste were favorable. The EEG results in their study showed neutral emotional responses for both brand types, yet half of consumers switched to private labels when price differences were highlighted, implying that price-sensitive consumers may overcome moderate brand loyalty if private-label quality is perceived as similar (29). Garczarek-Bak and Disterheft found that frontal beta asymmetry significantly predicted purchase decisions for fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs), especially national brands, which were three times more likely to be chosen than private labels. Lucchiari and Pravettoni reported higher reward-related beta power in EEG when participants consumed mineral water labeled with their favorite brand, suggesting brand-related familiarity and attachment enhance positive evaluations. Women showed stronger EEG responses for familiar (favorite) brands than men. Taken together, these studies highlight the interplay between pricing, emotional loyalty, and neural reward processes in driving brand preference (21).

Regarding brand extension and categorization, multiple ERP components (N270, N400, P300) were used to gauge the perceived “fit” between a parent brand (for example, a beverage) and potential extensions (for example, clothing, household appliances, or other services) (31-33, 37, 38). Ma et al. reported that stronger conflict, evidenced by larger N270/N400 amplitudes, arose when brand extensions lacked category congruence (31, 33). Jin et al. found the N400 to be smaller (reflecting ease of semantic integration) when brand extensions were closely related (for example, beverages), whereas unrelated extensions elicited heightened conflict (32). Yang et al. noted a two-stage process for service-to-service extensions, with initial detection of improbable extensions (P300) followed by semantic integration for mid-/high-fit categories (N400) (38). Yang and Kim confirmed the P300’s reliability in distinguishing high- vs. low-fit service brand extensions, with higher acceptance for high-fit categories (37). Jin et al. also showed that brand extension garnered faster decisions and higher acceptance when the product category was related, whereas creating a new brand became advantageous for unrelated product categories (32). Ma et al. introduced a t-SNE-LSTM model that accurately predicted participants’ acceptance or rejection of brand extensions (87 - 88% accuracy), underscoring the potential of advanced algorithms in neuromarketing (15). Overall, these findings demonstrate how neural markers of conflict (N270, N400) and categorization (P300, LPC) reliably detect fit or mismatch in brand-extension scenarios, with high perceived fit generally reducing cognitive load and increasing acceptance.

Studies focusing on brand personality, familiarity, and associations further illuminate rapid brand processing and underlying mechanisms. Handy et al. discovered that logos elicit hedonic evaluations in as little as 150 - 200 ms, emphasizing the speed and implicit nature of brand perception (34). Gholami Doborjeh et al. employed spiking neural networks (SNNs) to show that familiar logos produce more robust and widespread neural activation patterns than unfamiliar ones, corroborating faster and stronger memory retrieval (36). Xu et al. demonstrated that self-report data favored a similarity-attraction approach (Aaker’s framework), but EEG and GSR revealed subconscious divergences; “competence” personality types elicited the strongest physiological approach tendencies and appeared to particularly attract consumers high in openness (16). Camarrone and Van Hulle used the N400 to uncover implicit brand associations (for example, Netflix with “television”, Rex and Rio with “relaxation”) that traditional surveys did not detect (23), and Dini et al. found that incongruent logo-cue pairs triggered larger N400 and theta power, indicating semantic mismatch and higher cognitive load (22). These findings suggest that brand familiarity, personality alignment, and semantic congruity are key to fostering positive and rapid consumer-brand connections.

Another group of studies examined advertising, product placement, and tarnishment. Boshoff found that tarnished brand stimuli elicited neutral or mildly negative EEG/EMG responses, contrary to legal assumptions that tarnishment causes severe brand dilution. Slight negative responses were seen for some brands (for example, Starbucks), but overall tarnishment did not severely damage consumer perceptions or purchase intentions (35). Bosshard and Walla showed that evaluative conditioning changes brand attitudes more clearly in EEG signals than in self-reports or the IAT; negative stimuli also exerted stronger and longer-lasting conditioning effects than positive stimuli, highlighting the so-called “negativity bias” (20). Guo et al. used product placement disclosures in film or television and observed that disclosures increased brand memory but activated viewer skepticism, which then lowered brand attitudes. Eye-tracking and EEG data indicated higher attention in disclosure conditions, mediating both improved recognition and reduced favorability (18). Aliagas et al. discovered that incongruent brand placements in video games (for example, a sports brand in a racing context) captured more attention, induced higher cognitive load, and yielded better recall/recognition than congruent placements (25). Wang et al. showed that commercials with a clear narrative structure plus multiple product exposures (NS-ME) elicited stronger cognitive integration and emotional engagement (increased theta/beta/gamma power), significantly enhancing product preferences compared to non-narrative or single-exposure ads (24). Overall, these findings indicate that while certain disclosures or tarnishments can spark skepticism or mild negativity, strong narrative structures, creative incongruities, and repeated exposures can meaningfully shape recall, attitudes, and brand engagement.

Methodological advancements in neuromarketing are evident in the consistent use of EEG, ERP, and oscillatory measures. Studies demonstrated the value of N200, N270, N400, P300, and LPP as indicators of cognitive conflict, semantic integration, attentional engagement, and emotional arousal in brand-related tasks (19, 31-33, 37). Theta- and gamma-band power emerged as robust measures of cognitive load and emotional/motivational processing (24, 25). Integration of machine learning and advanced analytics is also increasingly common. The SNNs (36) and recurrent t-SNE neural networks (15) provided higher classification accuracy than traditional techniques (for example, SVM, PCA alone) in predicting brand-related decisions. Channel selection techniques (28) and data-driven clustering (23) further refined the extraction of brand-specific EEG signatures. Cross-modal approaches that combine EEG with eye-tracking, GSR, EMG, and behavioral tasks provided richer insights into consumer attention, emotional arousal, and conscious attitudes (16, 18, 35). Frontal asymmetry measures (26) also predicted purchase intentions, complementing more traditional ERP analyses. These advancements illustrate the field’s move toward more integrative methods that capture both conscious (self-report) and subconscious (physiological) facets of consumer behavior.

Despite methodological and contextual differences across the 25 studies, several consistent patterns emerged. Well-aligned (congruent) brand extensions and familiar brand stimuli generally reduced cognitive conflict and increased acceptance or positive evaluation, while incongruent or unfamiliar stimuli often heightened attention and memory but could also induce skepticism or negative affect if brand perceptions clashed with consumer expectations. The ERP components (N200/N270/N400/P300) and frontal asymmetry indices proved reliable indicators of conflict, semantic integration, emotional engagement, and purchase likelihood. The negativity bias and competence-based brand personality were recurring themes, and while strong loyalty or familiarity often supported manufacturer brands, competitive pricing or perceived quality could override brand preference (29). Enhanced neural “reward” responses (beta/gamma power) for favorite brands suggest robust emotional attachment can be a key differentiator. Social presence amplified responses to luxury brands (27), and repeated exposures or narrative-driven ads improved recall and preference (24). Tarnishment or disclosure effects tended to be mild or situational, challenging traditional assumptions of severe brand damage (18, 35). Machine learning and integrative data analyses (for example, eye-tracking plus EEG) are increasingly used to enhance the reliability and ecological validity of neuromarketing insights, although studies with small or homogeneous samples emphasize the need for broader participant pools and cross-cultural research to validate findings (Table 1).

| Ref. | Authors (y) | Approx. Sample Size | EEG Approach | Brand/Marketing Context | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brown et al. (2012) (29) | 12 | EEG+self-report | Manufacturer vs. private-label brands | Price strongly influenced brand switching, with half of participants switching to private-label when aware of cost differences. |

| 2 | Boshoff (2016) (35) | 24 | EEG+EMG | Brand tarnishment (legal/managerial context) | Mild brand tarnishment did not produce significant negative emotional or economic harm for established brands. |

| 3 | Handy et al. (2010) (34) | 16 | ERPs (P1, N2, LPP) | Rapid hedonic evaluations of logos | Disliked logos elicited stronger negative neural responses within ~150 - 200 ms, showing immediate, implicit aesthetic judgments. |

| 4 | Ma et al. (2007) (33) | 16 | ERPs (N270) | Brand extension (beverage brand to unrelated products) | Higher N270 amplitude reflected conflict when brand extensions were perceived as highly incongruent. |

| 5 | Jin et al. (2015) (32) | 18 | ERPs (N400) | Brand extension vs. new brand creation | N400 amplitude indicated stronger brand-product associations for well-matched extensions, faster decision-making for brand extensions. |

| 6 | Ma et al. (2008) (31) | ~16 | ERPs (P300) | Brand extension congruity | Larger P300 amplitudes for congruent extensions; Incongruent extensions triggered additional N400 conflict processing. |

| 7 | Wang et al. (2012) (30) | ~20 | ERPs (N400) | Unconscious brand extension categorization | N400 reflected automatic categorization; Incongruent extensions produced higher conflict activity even without explicit judgments. |

| 8 | Yang et al. (2018) (38) | ~30 | ERPs (N2, P300, N400) | Service-to-service brand extensions | Two-stage process: Early detection of improbable extensions (P300), then semantic integration (N400) for mid-/high-fit conditions |

| 9 | Gholami Doborjeh et al. (2018) (36) | 20 | SNN+ERP | Brand familiarity (logos) | SNN accurately classified familiar vs. unfamiliar logo responses; higher spiking intensity and broader connectivity for familiar logos |

| 10 | Yang and Kim (2019) (37) | 19 | ERPs (N2, P300) | Service-to-service brand extension (population-level) | Higher P300 amplitudes for high-fit stimuli, reflecting more robust and consistent semantic memory retrieval across participants |

| 11 | Fudali-Czyz et al. (2016) (39) | 20 | ERPs (N270, P300, N400) | Brand extension among indo-european speakers | Explicit categorization (N270/P300) drove acceptance or rejection; Incongruence triggered more negative N400. |

| 12 | Xu et al. (2023) (16) | 36 | EEG+GSR+self-report | Brand personality (competence, sincerity, etc.) | Discrepancies emerged between self-reported attraction and physiological measures, highlighting subconscious vs. conscious responses. |

| 13 | Bosshard and Walla (2023) (20) | 20 | EEG+IAT+self-report | EC and brand attitudes | EEG detected attitude shifts post-conditioning even when self-reports/IAT showed minimal changes; Negative EC had stronger effects. |

| 14 | Guo et al. (2018) (18) | ~40 | EEG+eye-tracking+self-report | Product placement disclosures | Disclosures boosted brand recognition (higher fixation times, frontal gamma) but reduced brand attitudes due to increased skepticism. |

| 15 | Zhang et al. (2019) (19) | ~20 (all female) | ERPs (N200, N400, LPP) | Luxury brands (authentic vs. counterfeit) | Counterfeit goods elicited larger N200/N400 for incongruent logos; Prominent counterfeit logos triggered higher LPP (self-presentation). |

| 16 | Wang et al. (2022) (17) | ~30 | EEG (theta-band oscillations)+behavioral | COO stereotypes and brand positioning | Theta-band activity indicated conflict for incongruent COO-positioning combos (competence vs. warmth); Congruence boosted purchase intent. |

| 17 | Wang et al. (2016) (24) | 30 | EEG spectral dynamics+behavioral | Narrative advertising and exposure frequency | Narratively structured+multiple exposures generated higher emotional engagement (theta/beta/gamma) and stronger product preferences. |

| 18 | Dini et al. (2022) (22) | 32 | ERPs (N400)+theta-band analysis | Brand logo congruity vs. incongruity | Incongruent logos triggered larger negative N400 and higher theta power, indicating semantic mismatch and greater cognitive load. |

| 19 | Lucchiari and Pravettoni (2012) (21) | 26 | EEG (theta, beta) | Brand attachment (mineral water labels) | Favorite brands showed reward-like beta increases; Unknown brands elicited higher frontal theta indicating conflict/uncertainty. |

| 20 | Camarrone and Van Hulle (2019) (23) | ~24 | ERPs (N400)+semantic priming | Brand association (Netflix vs. Rex&Rio) | N400 indicated distinct brand associations (TV vs. relaxation); Self-reports could not distinguish subtle differences in brand identity. |

| 21 | Ma et al. (2021) (15) | 22 | Recurrent neural network (t-SNE+LSTM) | Brand extension acceptance (EEG classification) | Model achieved ~85% accuracy in predicting acceptance/rejection; Outperformed standard classifiers by ~20%. |

| 22 | Garczarek-Bak and Disterheft (2018) (26) | 21 | EEG frontal asymmetry+logistic regression | Purchase decisions: National vs. private labels | Beta asymmetry predicted higher purchase intentions for national brands; GSR/EMG were not significant predictors. |

| 23 | Pozharliev et al. (2015) (27) | ~30 (females) | ERPs (P2, P3, LPP) | Emotional responses to luxury vs. basic brands (social context) | Luxury products elicited greater LPP in social presence; Social context amplified emotional responses compared to viewing alone. |

| 24 | Ozbeyaz (2021) (28) | 11 | EEG+ML (PCA+ANN) | Branded vs. unbranded smartphones | Achieved 72% accuracy in distinguishing branded vs. unbranded EEG responses; Frontal channels (AF3-F7) critical for classification. |

| 25 | Aliagas et al. (2024) (25) | ~28 (young gamers) | EEG+eye-tracking | In-game advertising (congruence, prominence, familiarity) | Incongruent brand placements captured more attention (longer fixations, higher theta), yielding better recall but increased cognitive load. |

Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalography; EMG, electromyography; ERP, event-related potential; SNN, spiking neural network; GSR, galvanic skin response; IAT, implicit association test; EC, evaluative conditioning; COO, country-of-origin.

4.4. Quality Assessment

Quality assessment using the QUADAS-2 tool (Table 2) showed that while most studies had low risk of bias in index testing (EEG methodology) and reference standards, concerns were notable in patient selection. Many studies demonstrated unclear or high risk of bias due to non-randomized, convenience sampling (e.g., university students). Applicability concerns regarding patient selection were prevalent across studies, reflecting limited generalizability from homogeneous samples to broader consumer populations. These findings highlight the need for more rigorous sampling methods in future research (Table 2).

| Titles | Authors (y) | Risk of Bias | Applicability Concerns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Selection | Index Test | Reference Standard | Flow and Timing | Patient Selection | Index Test | Reference Standard | ||

| A novel recurrent neural network to classify EEG signals for customers' decision-making behavior prediction in brand extension scenario | Ma et al. (2021) (15) | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low |

| The neurophysiological mechanisms underlying brand personality consumer attraction: EEG and GSR evidence | Xu et al. (2023) (16) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Country-brand fit: The effect of COO stereotypes and brand positioning consistency on consumer behavior | Wang et al. (2022) (17) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Applying eye tracking and EEG to evaluate the effects of placement disclosures on brand responses | Guo et al. (2018) (18) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Consumers implicit motivation of purchasing luxury brands: An EEG study | Zhang et al. (2019) (19) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Sonic influence on initially neutral brands: Using EEG to unveil the secrets of audio evaluative conditioning | Bosshard and Walla (2023) (20) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| The effect of brand on EEG modulation: A study on mineral water | Lucchiari and Pravettoni (2012) (21) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| EEG theta and N400 responses to congruent versus incongruent brand logos | Dini et al. (2022) (22) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Measuring brand association strength with EEG: A single-trial N400 ERP study | Camarrone and Van Hulle (2019) (23) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| EEG spectral dynamics of video commercials: Impact of the narrative on the branding product preference | Wang et al. (2016) (24) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Unravelling cognitive processing of in-game brands using eye tracking and EEG: Incongruence fosters it | Aliagas et al. (2024) (25) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| EEG frontal asymmetry predicts FMCG product purchase differently for national brands and private labels | Garczarek-Bak and Disterheft (2018) (26) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Merely being with you increases my attention to luxury products: Using EEG to understand consumers emotional experience | Pozharliev et al. (2015) (27) | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| EEG-based classification of branded and unbranded stimuli associating with smartphone products | Ozbeyaz (2021) (28) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| The story of taste: Using EEGs and self-reports to understand consumer choice | Brown et al. (2012) (29) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| N400 as an index of uncontrolled categorization processing in brand extension | Wang et al. (2012) (30) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| P300 and categorization in brand extension | Ma et al. (2008) (31) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Extending or creating a new brand: Evidence from a study on ERPs | Jin et al. (2015) (32) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| ERP N270 correlates of brand extension | Ma et al. (2007) (33) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| ERP evidence for rapid hedonic evaluation of logos | Handy et al. (2010) (34) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| The lady doth protest too much: A neurophysiological perspective on brand tarnishment | Boshoff (2016) (35) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Modelling peri-perceptual brain processes in a deep learning SNN architecture | Gholami Doborjeh et al.(2018) (36) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Group-level neural responses to service-to-service brand extension | Yang and Kim (2019) (37) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Characteristics of human brain activity during the evaluation of service-to-service brand extension | Yang et al. (2018) (38) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Controlled categorisation processing in brand extension evaluation by Indo-European language speakers: An ERP study | Fudali-Czyz et al. (2016) (39) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalography; GSR, galvanic skin response; ERP, event-related potential; COO, country-of-origin; FMCG, fast-moving consumer good.

4.5. Critical Appraisal of Included Studies

A critical synthesis of the included studies reveals consistent methodological limitations that temper the generalizability of the findings. The pervasive use of small, culturally homogeneous samples, primarily comprising young students, restricts the external validity and statistical power of the results. Furthermore, significant inconsistencies in EEG methodologies — including variations in electrode montages, preprocessing pipelines, and feature extraction — challenge the direct comparability and replication of findings across the literature. Addressing these limitations through larger, more diverse participant cohorts and the development of standardized EEG protocols is crucial for advancing the field of EEG-based neurobranding.

5. Conclusions

The EEG-based research in neurobranding has matured substantially over the past decade, transitioning from basic inquiries into consumer preference toward more sophisticated applications in marketing strategy development. Across the studies included in this review, there is broad consensus that EEG measurements, particularly from frontal and midline brain regions, offer valuable insights into consumers’ emotional responses, brand perceptions, and decision-making processes. Moreover, researchers have increasingly focused on digital marketing content, logos, and brand extensions, underscoring the growing importance of online and social media environments in shaping consumer attitudes.

Several methodological advances also emerged from this review. Pre-processing techniques such as ICA, PCA, and SNNs help denoise EEG data; however, care must be taken to ensure that essential neural information is preserved. On the feature extraction side, a variety of time, frequency, and time-frequency domain measures have been proposed, and the optimal choice depends on specific study objectives — whether it is detecting brand-related conflict, gauging emotional valence, or predicting purchase intention. Machine learning approaches, including ensemble methods, LSTM networks, and t-SNE-based models, have shown promising results in capturing nuanced aspects of consumer behavior, though traditional statistical techniques like ANOVA remain widespread for hypothesis testing and group comparisons.

Collectively, the studies underscore EEG’s capacity to clarify why consumers remain loyal to certain brands or become open to switching, how incongruent brand placements can amplify attention and memory, and how brand personality traits may activate different neural and behavioral pathways depending on consumer traits. Importantly, cultural context, sample diversity, and stimulus type (e.g., static logos vs. immersive gameplay) each shape the generalizability of findings. Future investigations can benefit from broader demographic samples, more ecologically valid stimuli, and multi-modal measures (e.g., EEG with eye-tracking, GSR, and facial EMG) to create a more holistic view of consumer responses.

By integrating neuroscience with advanced computational analyses, neuromarketing studies are increasingly equipped to provide marketers with actionable insights. Selecting the right EEG processing pipeline, features, and modeling approach depends on the problem at hand, the scope of data, and the research questions. As a result, we encourage future researchers to build on the strengths of existing work by employing rigorous protocols, validating findings in real-world brand contexts, and exploring cross-cultural dimensions. Ultimately, the findings from this review point to a rich and expanding field, wherein EEG-based neuromarketing research continues to refine our understanding of consumer decisions and to guide data-driven marketing strategies. We anticipate that these insights and recommendations will help researchers and practitioners align their methods and objectives more effectively, paving the way for innovative contributions in neurobranding.