1. Background

Diethylene glycol (DEG) is an alcohol formed through an ether linkage between two ethylene glycol molecules. This substance was first isolated in 1869 and subsequently introduced into industrial applications as a solvent in 1928. It is present in a vast array of products, including high-temperature furnace fuels, antifreeze agents, home decoration compounds, automotive chemicals, various pharmaceuticals, and numerous household consumables like (1). Studies have demonstrated the potential for this substance to induce detrimental effects on the nervous system. In vitro investigations have suggested that DEG can elicit neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells (2). Jamison Courtney et al. reported that oral administration of high DEG doses (4 - 6 g/kg) to rats resulted in spinal cord demyelination and neurotoxicity (3). A case study documented encephalopathy and rapid quadriplegia following the ingestion of a DEG-containing solution (4). Bilateral lower extremity numbness, peripheral facial nerve motor impairments, and abnormal nerve conduction in motor axons have been reported among individuals who survived a mass DEG poisoning incident in Panama in 2006 (5).

The median and average toxic and lethal doses of DEG vary and are limited. It is suggested that a minimum dose of 14 mg/kg can induce toxicity in humans (6, 7). According to European Union (EU) guidelines, the safe and non-toxic human dosage of DEG is approximately 1.6 milligrams per kilogram of body weight per day (8). The determination of this safe dose is primarily based on observations of DEG’s toxic effects on the liver, kidneys, and brain, rather than specific neurocognitive endpoints. Limited data exist on whether this regulated level is protective against subtle cognitive alterations. Specifically, within the nervous system, subtle functional deficits may only be detectable through sophisticated cognitive assessments. Therefore, the present study focused specifically on evaluating the cognitive impact of this EU-defined safe daily intake level (1.6 mg/kg/day) in rats. Investigating a broader dose range to establish a potential threshold for neurocognitive effects, while valuable, was considered beyond the scope of this initial assessment of the current guideline.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to assess the impact of sub-chronic (1-month) oral administration of DEG (at a dose of 1.6 mg/kg, considered safe by EU standards and chosen to directly evaluate this specific guideline) on cognitive functions, utilizing rodent models for learning and memory evaluation.

3. Methods

3.1. Ethical Approval

All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for animal research and were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences (IR.RUMS.AEC.1403.012).

3.2. Animals

For this study, 20 male Wistar rats, weighing between 200 - 250 g, were utilized. Animals were housed in sanitized cages within the animal facility at Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, maintained at a controlled temperature (22 - 24°C) and under a 12-hour light/dark cycle. They had unrestricted access to both water and standard rodent chow. Initially, 20 male Wistar rats were randomly assigned to two groups (n = 10 per group). The final number of animals included in the analysis for each behavioral test varied slightly (as indicated in the results and tables) due to minor animal attrition over the 30-day study period from causes (such as spontaneous illness) deemed unrelated to the DEG treatment.

3.3. Study Design

Subjects were randomly assigned to two groups (n = 10 per group). Group 1 received 1.6 mg/kg/day of DEG via oral gavage for one month. Group 2 (control group) received 2 mL/rat/day of saline solution via gavage for one month. To minimize stress associated with this daily procedure, all animals were gently handled by experimenters for 3 days prior to the initiation of the 30-day dosing regimen, accustoming them to the handling involved. Subsequently, spontaneous object recognition (SOR), elevated plus maze (EPM), Morris water maze (MWM), and passive avoidance (PA) paradigms were employed, with assessments conducted in both groups. To minimize potential bias, both the experimenters conducting the behavioral assessments and the individuals performing the subsequent data analysis were kept blind to the treatment conditions of the animals until all analyses were completed.

3.3.1. Spontaneous Object Recognition Test

This test comprised five stages: (1) Standard spontaneous object recognition (SSOR) test; (2) unimodal SOR; (3) tactile SOR; (4) visual SOR; and (5) cross-modal object recognition (CMOR). The protocol for these stages has been previously documented (9, 10).

3.3.2. Shuttle Box Test

A shuttle box apparatus (Panlab, Spain) was employed to evaluate avoidance memory. The procedures for shuttle box experiments have been previously described (11).

3.3.3. Morris Water Maze Test

The MWM paradigm, a commonly utilized tool in behavioral neuroscience, is designed for evaluating spatial learning and memory in rodents, notably rats and mice. The procedures for the MWM test have been detailed in prior publications (12).

3.3.4. Elevated Plus-Maze Behavioral Test

The EPM is a frequently employed behavioral assay for the assessment of anxiety-like behaviors in rodent models. The methodology is grounded in a model initially described by Pellow and File (13).

3.4. Data Collection Tool Specifications and Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 18). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Independent t-tests were utilized for comparisons between groups for data obtained from the elevated-plus maze, SOR tasks, shuttle box, and MWM probe trial. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was implemented for multiple group comparisons during the learning phase of the MWM assessment. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. The Effect of Diethylene Glycol on Different Forms of Spontaneous Object Recognition

The discrimination ratios (DR) for the four variants of the SOR task are presented in Table 1. Independent t-tests revealed no statistically significant differences in DR between the DEG and control groups for any of the SOR tasks. To further interpret these non-significant findings, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and post-hoc statistical power were calculated. For the standard SOR task, the observed difference in DR between the DEG group (0.2422 ± 0.4425, n = 9) and the saline group (0.6221 ± 1.1233, n = 7) corresponded to a small to medium effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ -0.47). Post-hoc power analysis indicated an achieved power of approximately 17.9% to detect such an effect, while the study had 80% power to detect a larger effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ 1.14). In the tactile SOR task, the difference in DR between the DEG group (-0.1575 ± 0.4302, n = 9) and the saline group (0.0290 ± 0.2287, n = 6) represented a medium effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ -0.51). The achieved power for this comparison was approximately 20.8%, with the study being adequately powered (80%) to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d ≈ 1.11. For the visual SOR task, the difference in DR between the DEG group (-0.1200 ± 0.3018, n = 9) and the saline group (-0.1316 ± 0.4487, n = 7) was very small (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.03). Consequently, the achieved power to detect such a minute effect was very low, approximately 5.1%, while the study had 80% power to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d ≈ 1.14. In the CMOR task, the difference in DR between the DEG group (0.1206 ± 0.4587, n = 9) and the saline group (0.2030 ± 0.2203, n = 7) was small (Cohen’s d ≈ -0.22). The achieved power for this comparison was approximately 9.0%, with 80% power to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d ≈ 1.14. Overall, while some small to medium effect sizes were noted, the study was generally underpowered to detect these as statistically significant across the SOR paradigms. The consistent lack of statistical significance suggests that within the sensitivity limits of the current study, primarily powered to detect larger effects, DEG exposure was not associated with detectable impairments in SOR memory, although very subtle effects cannot be entirely ruled out.

| Type of SOR and Metrics | Saline | DEG | t | df | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard SOR | 0.9333 | 14 | 0.3665 | ||

| DR | 0.62 ± 0.42, n = 7 | 0.24 ± 0.15, n = 9 | |||

| Tnovel (s) | 52.11 ± 3.18, n = 7 | 42.40 ± 2.94, n = 9 | |||

| Tfamiliar (s) | 11.74 ± 0.97, n = 7 | 27.20 ± 1.58, n = 9 | |||

| Ttotal (s) | 63.86 ± 3.38, n = 7 | 69.60 ± 4.27, n = 9 | |||

| Tactile SOR | 0.9662 | 13 | 0.3516 | ||

| DR | 0.03 ± 0.09, n = 6 | -0.16 ± 0.14, n = 9 | |||

| Tnovel (s) | 30.50 ± 0.76, n = 6 | 29.19 ± 1.97, n = 9 | |||

| Tfamiliar (s) | 28.50 ± 0.76, n = 6 | 37.98 ± 2.25, n = 9 | |||

| Ttotal (s) | 59.00 ± 1.53, n = 6 | 67.17 ± 3.96, n = 9 | |||

| Visual SOR | 0.06218 | 14 | 0.9513 | ||

| DR | -0.13 ± 0.17, n = 7 | -0.12 ± 0.10, n = 9 | |||

| Tnovel (s) | 29.00 ± 1.65, n = 7 | 31.33 ± 1.94, n = 9 | |||

| Tfamiliar (s) | 36.29 ± 2.35, n = 7 | 39.56 ± 2.65, n = 9 | |||

| Ttotal (s) | 65.29 ± 3.80, n = 7 | 70.89 ± 4.48, n = 9 | |||

| CMOR | 0.4355 | 14 | 0.6698 | ||

| DR | 0.20 ± 0.08, n = 7 | 0.12 ± 0.15, n = 9 | |||

| Tnovel (s) | 39.00 ± 2.45, n = 7 | 39.00 ± 2.67, n = 9 | |||

| Tfamiliar (s) | 26.00 ± 1.63, n = 7 | 28.00 ± 1.76, n = 9 | |||

| Ttotal (s) | 65.00 ± 3.78, n = 7 | 67.00 ± 3.65, n = 9 |

Abbreviations: SOR, spontaneous object recognition; DEG, diethylene glycol; DR, discrimination ratios; CMOR, cross-modal object recognition; Tnovel, time to explore novel object; Tfamiliar, time to explore familiar object; Ttotal, total exploration time.

a Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

b The DR was calculated as (Tnovel - Tfamiliar)/(Tnovel + Tfamiliar). The n value indicates the number of animals per group. n' represents the number of animals for which complete data were obtained for that specific test, reflecting minor animal attrition during the 30-day study period from an initial n = 10 per group.

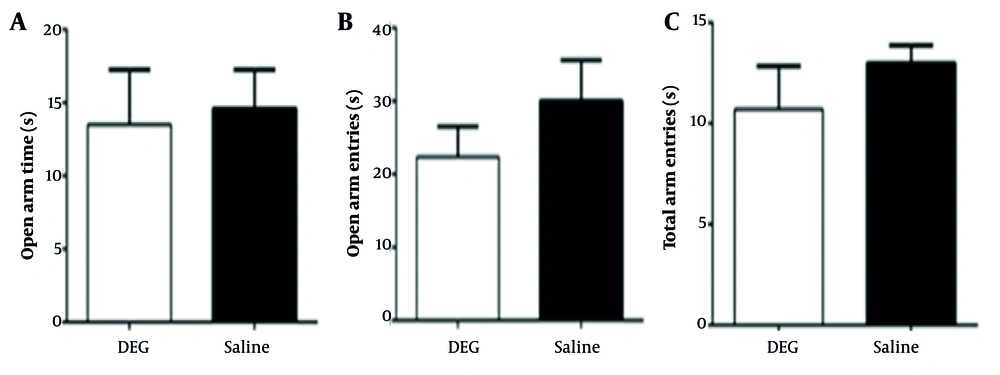

4.2. The Effect of Diethylene Glycol on Anxiety-Like Behavior

Independent t-test outcomes for the EPM revealed no statistically significant differences between the DEG and control groups across the examined parameters (Figure 1). For the average time spent in the open arms, the observed difference between the DEG group (13.50 ± 9.22 s, n = 6) and the saline group (14.61 ± 6.54 s, n = 6) was small (Cohen’s d ≈ -0.14). A post-hoc power analysis indicated that the achieved power to detect an effect of this magnitude was approximately 6.6%, while the study had 80% power to detect a much larger effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ 1.37). Similarly, for the percentage of entries into the open arms, the difference between the DEG group (27.96 ± 6.68 %, n = 8) and the saline group (30.05 ± 14.59 %, n = 7) was also small (Cohen’s d ≈ -0.19), with an achieved power of approximately 8.0%; for this measure, the study was adequately powered (80%) to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d ≈ 1.17. Finally, total arm entries (Figure 1C) also did not differ significantly between the DEG group (10.71 ± 5.65 entries, n = 7) and the saline group (13.00 ± 2.31 entries, n = 7). For this parameter, the observed effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ -0.53) was medium, and the achieved power was approximately 19.4%, with the study having 80% power to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d ≈ 1.21. Overall, these findings suggest that at the dose tested, DEG exposure was not associated with detectable changes in anxiety-like behaviors as measured by the EPM, though the study’s sensitivity was primarily limited to detecting larger effect sizes for most parameters.

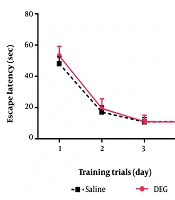

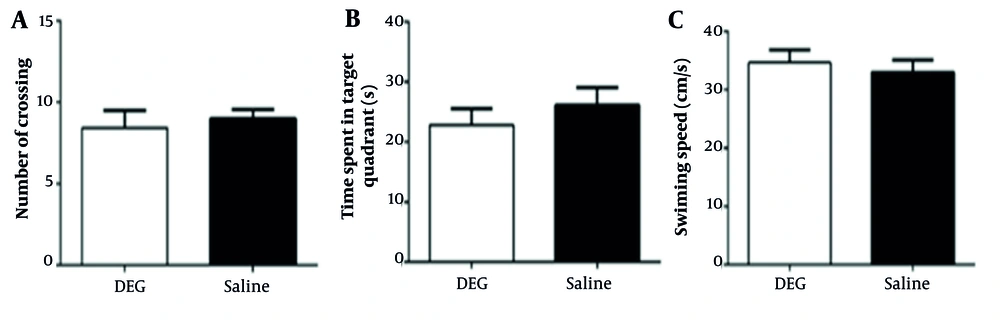

4.3. The Effect of Diethylene Glycol on Spatial Learning and Memory

The average latency to locate the hidden platform (an indicator of spatial learning ability) showed no difference between the DEG-treated and control animals over the training days (Figure 2). During the memory probe phase of the MWM test, animals in both the saline and DEG groups demonstrated a clear preference for the target quadrant (e.g., by spending significantly more time in the target quadrant compared to the average of the other three quadrants, data not shown), indicating successful retention of the platform’s location. For specific probe trial metrics (Figure 3), no statistically significant differences were found between groups. For the number of platform crossings, the difference between the DEG group (8.44 ± 3.17 crossings, n = 9) and the saline group (9.00 ± 1.53 crossings, n = 7) was small (Cohen’s d ≈ -0.22). Post-hoc power analysis indicated an achieved power of approximately 8.9% to detect such an effect, while the study had 80% power to detect an effect size (Cohen’s d) of ≈ 1.14. For the time spent in the target quadrant, the DEG group (22.83 ± 7.11 s, n = 7) and saline group (26.11 ± 8.78 s, n = 7) showed a small to medium difference (Cohen’s d ≈ -0.41). The achieved power for this comparison was approximately 13.8%, with the study being adequately powered (80%) to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d ≈ 1.21. Furthermore, swimming speed (Figure 3C) did not differ significantly between the DEG group (34.68 ± 5.73 cm/s, n = 7) and the saline group (32.99 ± 2.15 cm/s, n = 7), with a small observed effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.39). This comparability in swim speed indicates that DEG exposure did not overtly affect the animals’ motor function in this task. Overall, these analyses suggest that within the sensitivity limits of the current study, primarily powered to detect larger effects, DEG administration did not result in detectable impairments in spatial memory as assessed by the MWM probe trial.

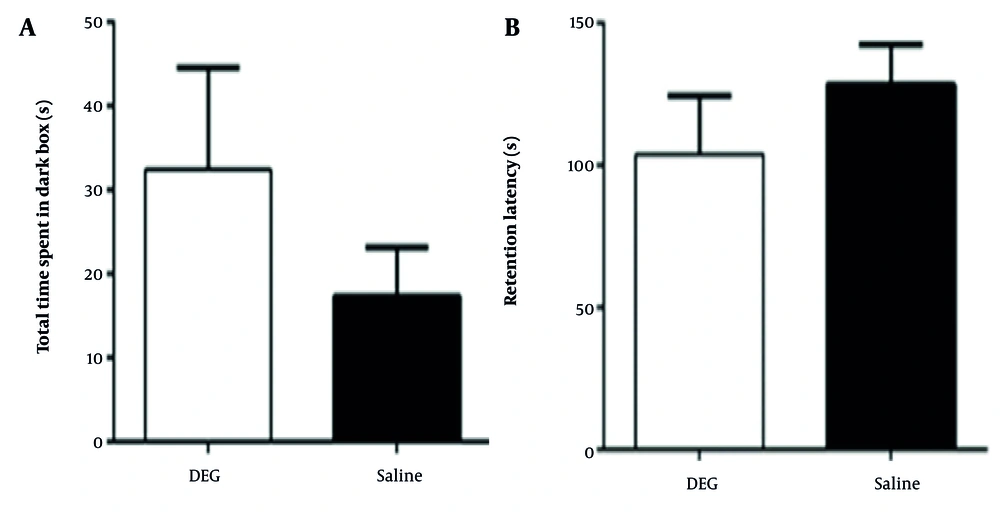

4.4. The Effect of Diethylene Glycol on Passive Learning and Avoidance Memory

In the passive avoidance test, no statistically significant differences were observed between the DEG and control groups for either retention latency or the total time spent in the dark compartment during the test phase (Figure 4). For retention latency, the DEG group (103.98 ± 58.09 s, n = 8) and the saline group (128.44 ± 34.41 s, n = 6) showed a small to medium difference (Cohen’s d ≈ -0.49). Post-hoc power analysis indicated an achieved power of approximately 20.3% to detect an effect of this magnitude, while the study had 80% power to detect an effect size (Cohen’s d) of ≈ 1.26. Regarding the total time spent in the dark compartment, the DEG group (32.43 ± 32.11 s, n = 7) and saline group (17.37 ± 15.32 s, n = 7) exhibited a medium difference (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.60). The achieved power for this comparison was approximately 23.8%, with the study being adequately powered (80%) to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d ≈ 1.21. These analyses suggest that while some medium-sized differences were observed, particularly for time spent in the dark compartment, the study was underpowered to detect these as statistically significant. Overall, within the sensitivity limits of the current study, DEG administration was not associated with detectable impairments in passive avoidance learning and memory.

5. Discussion

The results of this study indicated that administering 1.6 mg/kg/day of DEG for 30 days in rats did not appear to produce readily detectable detrimental effects on higher cognitive brain functions, including exploratory, spatial, and avoidance capabilities. Anxiety-related behaviors also appeared unaffected by DEG exposure. Diethylene glycol is recognized as a hazardous substance; ingestion can lead to mortality and severe complications across various organ systems, including the renal and nervous systems (1). While the precise mechanisms of damage remain incompletely understood, toxicity is likely dose-dependent (14). Given suggestions that DEG poisoning can symmetrically affect the basal ganglia, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, brainstem, and white matter, it is plausible that DEG could indirectly influence learning and memory processes. Hasbani et al. reported a case of encephalopathy and rapid quadriplegia in an individual following consumption of a DEG-containing solution. Data suggest that DEG poisoning may induce acute primary axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy (4). Sosa et al. also characterized DEG poisoning resulting from contaminated cough syrup distributed in Panama in 2006 (15). In addition to acute kidney damage, most patients with DEG poisoning also exhibited progressive neurological signs and symptoms (16). A 2015 study reported that exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) at concentrations of 50,200 mg/kg/d reduced NR1 and NR2B subunit levels of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor in the hippocampus of juvenile mice, leading to learning and memory deficits (17). While DEHP is a different compound, this finding highlights that environmental chemicals can indeed modulate critical synaptic components like NMDA receptors, which are well-known for their essential role in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. Although our current behavioral study at a low DEG dose did not reveal cognitive deficits, it is plausible that DEG, particularly at higher exposure levels or through different mechanisms not captured by our behavioral tests, could also interfere with such neurochemical pathways. Therefore, future molecular investigations are crucial. For instance, examining the expression levels of NMDA receptor subunits, such as NR2B, in key brain regions like the hippocampus following DEG exposure, as suggested by the reviewer, could provide valuable insights into its potential neurochemical impact. Such studies, alongside electrophysiological assessments of synaptic function, would help to elucidate whether DEG can alter neuronal excitability or plasticity even in the absence of overt behavioral changes at low doses, or at doses approaching a toxic threshold.

These established neurotoxic effects at high doses are in stark contrast to the findings of the current study. Here, using a DEG dose of 1.6 mg/kg/day – representing the maximal safe human daily intake level according to EU guidelines – administered for 30 days, we did not observe impairments in the assessed measures of memory, learning, or anxiety-like behavior in rats. Diethylene glycol dose of 1.6 mg/kg/day used in our study, considered a safe reference for human intake by the EU based on kidney, liver, and brain effects, is substantially lower than the No observed adverse effect levels (NOAELs) typically reported for renal toxicity in rats exposed to a related compound, ethylene glycol (which are often in the range of 50 - 200 mg/kg/day in subchronic studies). This highlights differing potencies even among related glycols, though a detailed comparative toxicological review is beyond our current scope.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, while it is well-established in the literature, including reports of significant neurotoxicity such as spinal cord demyelination at high doses (e.g., 4 - 6 g/kg in rats), the findings from the present study suggest that sub-chronic oral administration of a comparatively very low dose of DEG (1.6 mg/kg/day for 30 days) did not result in detectable impairments in the specific cognitive functions (object recognition, spatial learning and memory, passive avoidance) or anxiety-like behaviors assessed in male Wistar rats. This underscores the critical importance of dose in determining DEG’s toxicological profile. Nevertheless, these findings should be interpreted within the scope of the behavioral paradigms employed and the exposure duration. Further investigations, potentially employing molecular and electrophysiological techniques, as well as examining longer exposure periods or more sensitive neurological endpoints, are warranted to provide deeper insights into the full spectrum of potential effects of chronic low-level DEG exposure on neuronal physiology and complex behaviors.

5.2. Study Limitations

While the quantitative MWM data (e.g., time in target quadrant, platform crossings) indicated no impairment in spatial memory, the study would have been strengthened by the inclusion of qualitative data such as heatmaps or path traces from the probe trial to visually confirm search strategies; however, these detailed raw tracking outputs were not available from the original dataset. Additionally, while swim speed in the MWM was unaltered, indicating no gross motor impairments that would confound cognitive testing in that apparatus, the study did not include a dedicated test of fine motor coordination and balance, such as the rotarod. Future studies could incorporate such measures for a more comprehensive assessment of potential neuromotor effects.

A consideration in interpreting the uniform lack of statistically significant findings in this study is statistical power. Post-hoc power analyses revealed that with the current sample sizes, the study was adequately powered to detect large effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d > ~1.1 - 1.3 depending on the test) for the primary outcome measures. However, the observed effect sizes for the differences between the DEG and saline groups were generally in the small to moderate range. Consequently, the achieved power to detect these specific observed differences was low. While the consistent pattern of non-significance across multiple cognitive domains suggests that DEG at 1.6 mg/kg/day for 30 days does not exert a strong, readily detectable influence, the possibility of a true, but very subtle, type II error cannot be entirely excluded. Future studies employing larger sample sizes would be beneficial to more definitively assess potential effects of very small magnitudes.

It is crucial to emphasize that the findings of this study, which indicate a lack of detectable cognitive impairment, are specific to the low dose of DEG administered (1.6 mg/kg/day) and the 30-day sub-chronic exposure period in adult male Wistar rats. These results cannot and should not be generalized to scenarios involving higher doses or more prolonged, chronic exposures. As discussed, DEG exhibits clear dose-dependent toxicity, with severe neurological and renal effects documented at high exposure levels. Similarly, the potential for cumulative effects or different toxicological profiles to emerge with truly chronic low-level exposure warrants distinct investigation. Therefore, further research is required to understand the potential risks associated with higher acute or sub-chronic doses of DEG, as well as the consequences of long-term, continuous exposure, even at levels currently considered safe for shorter durations. Such studies should also consider different developmental stages and potentially more sensitive or diverse neurological endpoints.

A further limitation is the absence of histopathological analysis (e.g., assessment of neuronal integrity or cell counts in brain regions like the hippocampus) to provide structural correlates for our behavioral findings. While no overt behavioral deficits were detected at the low dose of DEG used, such analyses would be essential in future studies, particularly if investigating higher doses or longer exposure periods, to more comprehensively evaluate DEG’s potential impact on brain structure.

An important consideration, particularly for the SOR tasks, was the notable inter-individual variability observed in some parameters, as reflected by relatively large standard errors of the mean (SEMs) compared to the group means (e.g., for tactile and standard SOR in the control group, Table 1). Such variability is not uncommon in tests relying on spontaneous exploratory behavior, which can be influenced by intrinsic individual differences in temperament or subtle environmental factors. This high variability inherently reduces the statistical power to detect subtle differences between experimental groups and underscores the need for cautious interpretation of non-significant findings in these specific SOR paradigms. While our power analyses (discussed elsewhere) considered overall study power, this task-specific variability further emphasizes that any potential subtle effects of DEG in these SOR tests might have been obscured.