1. Background

Interscalene block (ISB) is a gold-standard regional anesthetic for upper extremity procedures, particularly shoulder surgery, offering superior perioperative analgesia, reduced opioid use, shorter PACU stays, and higher patient satisfaction compared to general anesthesia (1). Three ISB techniques exist: (1) The classic Winnie approach, targeting the C5 - C6 nerve roots via palpation of the interscalene groove (2, 3); (2) Nerve stimulator-guided methods using electrical impulses to locate the brachial plexus (C5 - C7); and (3) Ultrasound-guided ISB, which improves precision by visualizing nerves and adjacent structures, reducing complications like phrenic nerve palsy (4, 5). Combining ultrasound with nerve stimulation further enhances accuracy, safety, and clinical outcomes by confirming needle placement and anesthetic spread (6, 7).

Despite its efficacy, ISB carries risks such as diaphragmatic paralysis due to phrenic nerve involvement (8), Horner's syndrome by constriction of the stellate ganglion (9), and dissemination of local anesthetic (LA) to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which may result in transient hoarseness (10). Local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) is a considerable risk when LA is injected into vital vascular structures (11), and rarely, pneumothorax (12). The ISB with a standardized technique has a very high success rate, inducing a profound motor blockade of the upper limb musculature, potentially affecting the hand muscles, which may result in postoperative patient discomfort and muscle weakness (13). Additionally, postoperative neurologic symptoms (PONS) are acknowledged problems highly associated with both ISB and orthopedic shoulder surgery. Generally, it may be induced by direct trauma from surgical dissection, manipulation of the ISB needle, or intraneural injection. Even the pharmacological feature of LA injection may also result from ischemia caused by nerve traction during surgical positioning or from nerve compression due to excessive volumes of ISB injectate or intra-articular surgical irrigation. These symptoms typically resolve within weeks to months; however, they may encompass chronic pain, paresthesia, sensory or motor deficits in a peripheral nerve, or radicular distribution (13, 14). Although there was a high incidence of transient problems with ISB, including paresthesia, dysesthesia, or pain not related to surgery (14% at 10 days postoperatively), very few patients experienced long-term complications (0.4%) (15).

The choice of LA agents, specifically ropivacaine and bupivacaine, is crucial for the efficacy, safety, and duration of an ISB. Adjusting the volume and concentration of these agents is essential for optimizing analgesic efficacy and minimizing potential complications (16). Bupivacaine is a long-acting amide-type LA used in regional anesthesia, blocking voltage-gated sodium channels within neuronal membranes, causing sensory and motor blockade, and is typically administered in concentrations ranging from 0.25% to 0.5% (17). Its metabolism primarily occurs in the liver via cytochrome P450 enzymes and is eliminated renally with advantageous rapid onset and prolonged duration of action, making it suitable for comprehensive surgical procedures. However, elevated concentrations may lead to extensive motor blockade and possible complications due to pronounced affinity for sodium channels; bupivacaine poses a significant risk of cardiotoxicity at augmented plasma concentrations and phrenic nerve palsy (18, 19).

Ropivacaine is a long-acting amide-type LA developed as the pure S(-)-enantiomer. Its anesthetic effects involve reversibly inhibiting sodium ions within nerve fibers, blocking action potential propagation, favoring nociceptive Aδ and C fibers while sparing motor Aβ fibers, resulting in significant sensory blockade and reduced motor impairment (20). It represents a safer option in regional anesthesia due to its lower lipophilicity and stereoselective properties.

Its linear pharmacokinetic profile involves extensive hepatic system metabolism, primarily involving cytochrome P450 enzymes, with minimal renal excretion (21). Ropivacaine and bupivacaine in 0.5% concentration form exhibit similar clinical features when utilized for ISB, offering a comparably prolonged duration of postoperative analgesia. Ropivacaine has the additional benefit of a reduced risk for central nervous system and cardiovascular damage (22). Both LA agents are thought to exert a deleterious effect on the muscles post-injection, contributing to PONS. Bupivacaine and ropivacaine may cause irreversible skeletal muscle damage in a clinical model, with bupivacaine's myotoxicity exceeding that of ropivacaine (23).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to compare bupivacaine 0.5% and ropivacaine 0.5% utilizing ISB by a combined nerve stimulator and ultrasound-guided technique to determine which agent is more closely associated with PONS (weakness) as assessed by handgrip dynamometer monitoring.

3. Methods

Randomized Single-Blinded Study Design: A total of 120 patients undergoing shoulder surgery with ISB were included in this study. Participants were randomized into two groups, with 60 patients in each group for ropivacaine and bupivacaine. Randomization was conducted in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated sequence (block randomization, block size of 4). Allocation concealment was maintained via sealed opaque envelopes, which were opened by a non-study anesthesiologist.

To enhance the precision of the findings and to delineate the study's aims across various age demographics, each group was further segmented into three subcategories based on the age of the participants. Each subgroup comprised 20 patients: Young (15 - 30), middle-aged (31 - 50), and geriatric (51 - 70). Patients and outcome assessors (handgrip dynamometer operators) were blinded to the anesthetic agent. The performing anesthesiologist was not blinded due to procedural requirements, but postoperative data collectors had no access to group assignments. Surgical duration was recorded from incision to closure.

3.1. Pre-interscalene Block Performance

Before the ISB procedure execution, patients provided comprehensive consent for surgery under regional anesthesia and participation in the study after reviewing the research consent form documentation. An assessment was conducted to determine the indications and avoid contraindications. Informed consent was obtained for potential complications such as phrenic nerve palsy, Horner's syndrome, and recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement. Finally, muscle power baselines were obtained using an electronic handgrip dynamometer, and readings were documented in the research design chart.

3.2. Post-interscalene Block Performance

The research team avoids sedation as much as possible during ISB, and IV morphine is administered for irritable patients with arousable state conditions. Muscle power was recorded immediately after LA injection using a handgrip dynamometer device and every 10 minutes for 50 minutes before the patient was admitted to the operating theater. Intraoperatively, the patient was sedated with a propofol infusion. Additionally, the team sought to understand surgeons' satisfaction levels during surgery by assessing easy muscle intervention, a clear view of the surgical field, and lax extremity for traction purposes to evaluate the effect of study agents (bupivacaine and ropivacaine) on muscle power. After 3 hours, the surgery is generally over, and the patient is taken to the PACU for observation. Propofol's sedative effects are depleted, so the patient is aware, and muscle power should be ready to be recorded at this point. Furthermore, muscle strength was assessed twice, once within 12 and 24 hours after the patient was discharged.

3.3. One Week After Surgery

To obtain accurate results, the research team continuously monitors the effect for a longer period. The patients participating in this study underwent a final muscle strength test upon their arrival at the fracture surgery consulting clinic after the operation.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed by mean muscle power (MMP), standard deviation (SD), the repeated ANOVA (two-way) test (normal distribution) for comparing more than two groups (before, after, immediately, and follow-up after ISB patients), and post hoc by Tukey's test for pairwise comparison. Correlation analysis used Pearson correlation with a 95% confidence interval (CI) between MMP (kg) and age (years) of patients. The relationship map for the categories studied was calculated. Logistic regression analysis obtained the odds ratio (OR) and a 95% CI. Differences with P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Data analysis was performed with SPSS v. 28, and graphics with Excel software 2021.

4. Results

4.1. Ropivacaine Group

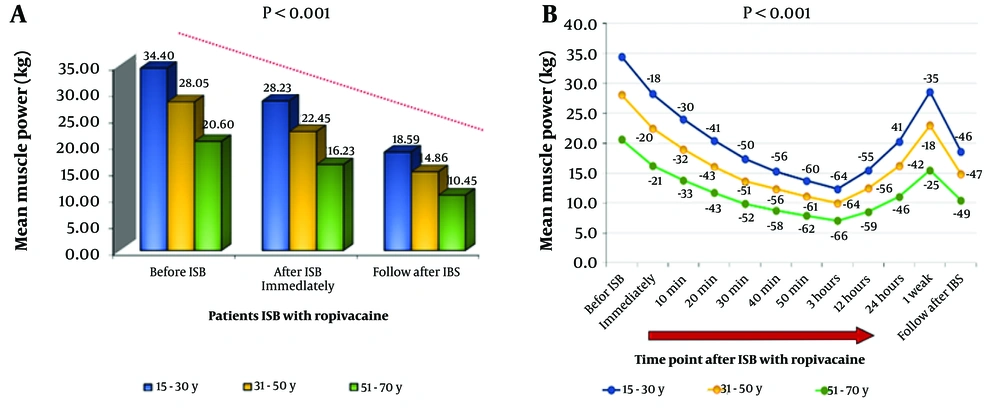

As shown in Figure 1, ropivacaine induced a progressive reduction in motor strength across all age groups (baseline to 1 week; P < 0.001). The MMP before ISB injection (baseline) for each group (15 - 30, 31 - 50, and 51 - 70 years) was 34.40 ± 11.67, 28.05 ± 10.63, and 20.60 ± 8.15, respectively (Figure 1A).

A, effect of 0.5% ropivacaine on handgrip muscle strength following Interscalene block (ISB) across age groups; bar chart depicting mean muscle power (MMP) (kg) measured using a handgrip dynamometer in three age groups: Fifteen to thirty years (blue), 31 - 50 years (yellow), and 51 - 70 years (green). Measurements were taken at three time points: Before ISB, immediately after ISB, and during follow-up post-ISB. All groups showed a statistically significant reduction in muscle strength post-ISB (P < 0.001), with older patients demonstrating both lower baseline strength and slower recovery. The 15 - 30-year group exhibited the highest recovery, while the 51 - 70-year group had the lowest muscle power at all time points; B, time-course of muscle strength reduction and recovery following ISB with 0.5% ropivacaine in different age groups; line graph illustrating changes in mean handgrip muscle power (kg) over time in three age groups: Fifteen to thirty years (blue), 31 - 50 years (orange), and 51 - 70 years (green). Measurements were taken before ISB and at multiple time points up to one-week post-procedure. All groups showed a significant decline in muscle strength post-ISB (P < 0.001), with the lowest values observed between 40 minutes and 3 hours. Younger patients (15 - 30 years) demonstrated the highest baseline strength and the fastest recovery, reaching near-baseline levels by one week. Older age groups experienced a more pronounced and prolonged motor block, with delayed and incomplete recovery. The data highlight age-dependent variability in the onset, depth, and duration of motor impairment following ISB with ropivacaine.

4.1.1. Surgical Duration

The mean surgical duration was 98 ± 22 minutes (range: 65 - 140), with no significant difference between groups (P = 0.34). Block duration and recovery profiles remained consistent regardless of surgical time.

4.1.1.1. From Baseline to 50 Minutes

A. Young age: Muscle power dropped by -18% (immediate), -30% (10 min), -41% (20 min), -50% (30 min), -56% (40 min), and -60% (50 min). The MMP sequence was 28.23 ± 9.50, 24.00 ± 8.03, 20.40 ± 6.86, 17.35 ± 5.84, 15.28 ± 5.17, and 13.70 ± 4.73, respectively.

B. Middle age: There was a more rapid decline: -20% (immediate), -32% (10 min), -43% (20 min), -51% (30 min), -56% (40 min), and -61% (50 min). The MMP sequence was 22.45 ± 8.42, 18.98 ± 7.12, 16.03 ± 6.07, 13.65 ± 5.23, 12.33 ± 4.69, and 11.08 ± 4.18, respectively.

C. Geriatric: An early decline was observed: -21% (immediate), -33% (10 min), -43% (20 min), -52% (30 min), -58% (40 min), and -62% (50 min). The MMP sequence was 16.23 ± 6.37, 13.80 ± 5.49, 11.68 ± 4.74, 9.85 ± 3.99, 8.75 ± 3.53, and 7.88 ± 3.26.

4.1.1.2. Maximal Motor Weakness (3 Hours Post-interscalene Block)

A. Young age: Minimum -64% MMP (12.33 ± 4.23).

B. Middle age: -64% MMP (9.98 ± 3.79).

C. Geriatric: More -66% MMP (7.05 ± 2.99).

4.1.1.3. Muscle Recovery (12 Hours Post-interscalene Block)

A. Young age: Forty-five percent rescue MMP (15.48 ± 5.36).

B. Middle age: Forty-four percent rescue MMP (12.45 ± 4.76).

C. Geriatric: Forty-one percent MMP (8.54 ± 3.54).

4.1.1.4. Partial Recovery (24 Hours to 1 Week)

A. Young age: The rescue resulted in 9% MMP (20.24 ± 6.88) and 65% MMP (28.55 ± 9.20).

B. Middle age: Rescue 58% MMP (16.18 ± 6.17), 82% MMP (22.95 ± 8.58).

C. Geriatric: Rescue 54% MMP (11.06 ± 4.62), 75% MMP (15.48 ± 6.30) (Figure 1B).

4.2. Bupivacaine Group

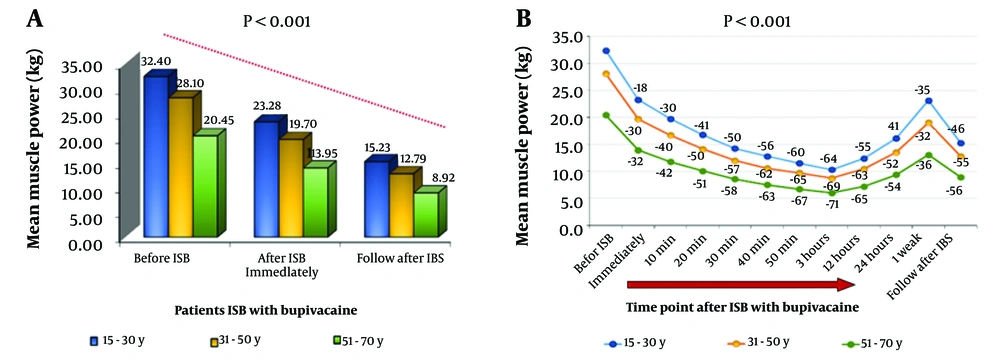

As shown in Figure 1, the study found a significant decline and partial recovery of strength post-ISB, indicating the pharmacodynamic consistency of bupivacaine across all age groups, with more time-dependent reductions than the ropivacaine group. The MMP was assessed at baseline. The youngest group exhibited the highest MMP at 32.40 kg, followed by the middle-aged and geriatric groups at 23.28 kg and 12.79 kg, respectively (Figure 2A).

A, effect of 0.5% bupivacaine on handgrip muscle strength following Interscalene block (ISB) across age groups; bar chart showing mean handgrip muscle strength (kg) in patients aged 15 - 30 years (blue), 31 - 50 years (yellow), and 51 - 70 years (green) at three time points: Before ISB, immediately after ISB, and during follow-up. All groups experienced significant reductions in muscle power post-ISB (P < 0.001), with greater reductions and slower recovery in older patients. Younger participants started with higher baseline strength and showed better recovery. However, the elderly group (51 - 70 years) demonstrated both the lowest initial strength and the most pronounced and prolonged weakness, with incomplete recovery by the follow-up period. These findings highlight the age-dependent effects of bupivacaine on motor block intensity and recovery duration. B, time-course of muscle strength reduction and recovery following ISB with 0.5% bupivacaine in different age groups; line graph illustrating changes in mean handgrip muscle power (kg) over time in three age groups: Fifteen to thirty years (blue), 31 - 50 years (orange), and 51 - 70 years (green). Measurements were taken before ISB and at multiple time points up to one-week post-procedure. All groups showed a significant decline in muscle strength post-ISB (P < 0.001), with the lowest values observed between 40 minutes and 3 hours. Younger patients (15 - 30 years) demonstrated the highest baseline strength and the fastest recovery, reaching near-baseline levels by one week. Older age groups experienced a more pronounced and prolonged motor block, with delayed and incomplete recovery. The data highlight age-dependent variability in the onset, depth, and duration of motor impairment following ISB with ropivacaine.

4.2.1. From Baseline to 50 Minutes

A. Youngest (shows no difference with ropivacaine): -18% (immediate), -30% (10 min), -41% (20 min), -50% (30 min), -56% (40 min), and -60% (50 min). The MMP sequence was 23.28 ± 8.64, 19.73 ± 7.57, 16.78 ± 6.40, 14.24 ± 5.44, 12.83 ± 4.97, and 11.53 ± 4.49, respectively.

B. Middle age (exhibits a more rapid decline): -30% (immediate), -40% (10 min), -50% (20 min), -57% (30 min), -62% (40 min), and -65% (50 min). The MMP sequence was 19.70 ± 8.19, 16.73 ± 7.03, 14.15 ± 5.92, 12.00 ± 5.03, 10.58 ± 5.00, and 9.73 ± 4.17, respectively.

C. Elderly: It also experiences a more rapid decline, with percentages of -32% (immediate), -42% (10 min), -51% (20 min), -58% (30 min), -63% (40 min), and -67% (50 min). The MMP sequence was 13.95 ± 5.43, 11.78 ± 4.50, 10.08 ± 3.88, 8.58 ± 3.28, 7.53 ± 2.91, and 6.70 ± 2.73, respectively.

4.2.2. Maximal Motor Weakness (3 Hours Post-interscalene Block)

A. Young age: -64% MMP (10.33 ± 4.10).

B. Middle age: -69% MMP (8.75 ± 3.79).

C. Elderly: -71% MMP (6.00 ± 2.56).

4.2.3. Muscle Recovery (12 Hours After Interscalene Block)

A. Young age: Shows a 45% rescue in ropivacaine MMP (12.40 ± 4.96).

B. Middle age: Shows a 37% rescue MMP (10.47 ± 3.00).

C. Elderly: Shows a 35% MMP (7.20 ± 3.09).

4.2.4. During the Partial Recovery Phase (24 Hours to 1 Week)

A. Young age: Shows a 9% rescue in MMP (16.15 ± 6.40) and 65% MMP (23.13 ± 8.98).

B. Middle age: Rescue 48% MMP (13.55 ± 5.00) and 68% MMP (19.04 ± 7.10).

C. Elderly: Rescue 46% MMP (9.38 ± 4.03) and 64% MMP (13.08 ± 5.50) (Figure 2B).

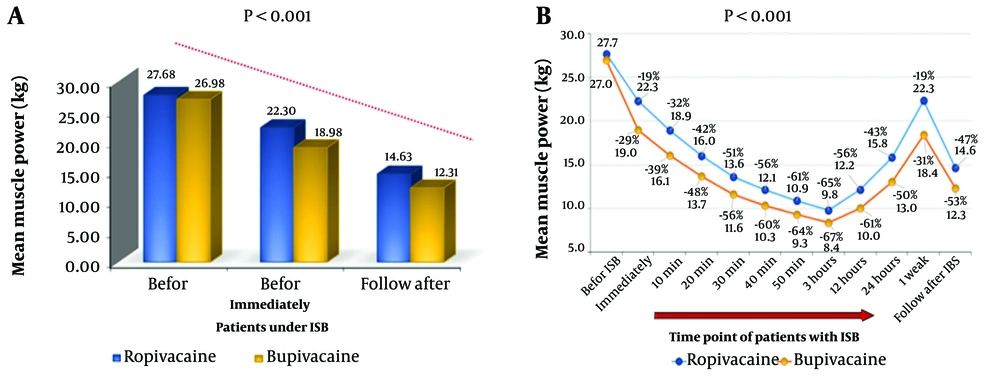

4.3. Primary Compression

The MMP (baseline) for bupivacaine and ropivacaine was 26.98 ± 11.72 and 27.68 ± 11.57, respectively, revealing significant differences in motor blockade onset, depth, and recovery kinetics (P < 0.001). Both agents exhibit age-dependent effects and key pharmacodynamic profiles. Immediately after ISB, ropivacaine maintained superior muscle strength (22.30 ± 9.46 kg) compared to bupivacaine (18.98 ± 8.37 kg; P < 0.003), suggesting a less profound initial motor blockade. The bupivacaine group lost approximately 50% of the baseline MMP at the beginning of the 2nd tenth minute, whereas ropivacaine extended to 30 minutes, indicating bupivacaine's aggressive motor block profile. The MMP at peak blockade (3 hours post-ISB) was markedly lower with bupivacaine (12.31 kg) than with ropivacaine (14.63 kg), corroborating its stronger motor-suppressive effect. Bupivacaine achieved earlier and more pronounced nadir values (10.02 ± 4.72 kg at 12 hours vs. ropivacaine’s 12.15 ± 5.37 kg), reflecting its longer-acting properties. By 24 hours, the ropivacaine group regained approximately 57% of baseline strength (15.82 ± 6.98 kg), whereas the bupivacaine group recovered only approximately 50% (13.03 ± 6.13 kg). At 1 week, ropivacaine’s near-complete recovery of approximately 80% (22.33 ± 9.64 kg) surpassed bupivacaine’s approximately 70% (18.41 ± 8.65 kg), aligning with its reputation for faster motor recovery (Figure 3A and B).

A, comparison of motor strength (kg) before and after Interscalene block (ISB) using ropivacaine versus bupivacaine; the bar graph depicts mean muscle power (MMP) (kg) measured via a handgrip dynamometer. Before ISB: Baseline muscle strength (control). After ISB: Post-block measurements for ropivacaine (blue) and bupivacaine (yellow). Both anesthetics significantly reduced muscle strength post-ISB (P < 0.001). Bupivacaine showed a more pronounced reduction compared to ropivacaine. B, comparison of motor power reduction (%) between ropivacaine and bupivacaine after ISB; Both anesthetics show significant strength reduction (P < 0.001) with maximal effect at peak time points. Progressive motor power decline following ISB with ropivacaine (blue) and bupivacaine (yellow). Percentages indicate strength reduction from baseline, with both groups reaching > 50% reduction (P < 0.001).

5. Discussion

With advancing age, sarcopenia, a decline in muscle strength, begins in the fourth decade and intensifies around age 60. Baseline strength varies with age, with younger individuals having the most strength, middle-aged individuals having moderate strength, and the elderly experiencing the lowest strength (24). Age-stratified comparisons of motor block characteristics following ISB reveal significant differences between ropivacaine and bupivacaine regarding the onset, depth, and recovery of muscle strength. Ropivacaine (0.5%, 30 mL) demonstrated a moderate motor block with a relatively rapid onset (peak effect at 30 - 45 minutes), leading to muscle strength reductions of 18%, 20%, and 21% from baseline in young, middle-aged, and elderly participants. The time spent to reduce 50% of the baseline MMP was 30 min ± 5 (24). In contrast, in the bupivacaine 0.5% group, muscle power decreased rapidly across all age groups, with the most pronounced weakness observed in middle-aged and elderly groups (30% and 32%, respectively) (20 ± 5 min) to achieve a loss of half-baseline muscle strength (25). The young group still held an 18% reduction as observed in ropivacaine, which explains how Klein et al. and Casati et al. (2000) estimate there is no clinical difference in onset and duration (22, 26). The MMP immediately after injection was more aggressive than ropivacaine (19%), indicating a greater degree of onset of motor block features (27). Both groups hit a lower point of block at 3 hours after the injection, with a loss of baseline MMP (65%, 67%) for ropivacaine and bupivacaine, respectively (28). The young age of both groups shows the same pattern of MMP (29). There is a difference in blocking level across ages, which aligns with a study by Gragasin and Tsui suggesting that aging enhances sensitivity to LAs due to structural and functional changes in peripheral nerves, including decreased myelination and slower nerve conduction velocity (30). After 12 - 24 hours from injection, muscle power recovery was greatest in the young group, regaining 45% - 60%, respectively, and the same with ropivacaine young group findings (29), while middle-aged and elderly groups suffered delayed muscle power rescue, reaching 50% of recovery after 24 hours (31, 32). After one week, MMP recovery was greater with ropivacaine, gaining 80% of muscle power, while it was 70% with bupivacaine. All groups remained > 30% below the baseline effect, aligning with bupivacaine's pharmacological properties, including enhanced sodium channel affinity and lipophilicity (33).

5.1. Conclusions

Bupivacaine demonstrated a faster onset, more profound motor block, and prolonged duration compared to ropivacaine, and is more pronounced with PONS, especially in middle-aged and elderly individuals who suffer postoperative muscle weakness for up to one week.

5.2. Limitations

Orthopedic surgery and regional anesthesia are linked to PONS. During shoulder surgery, direct trauma, nerve compression, and ischemia can cause PONS in the operative arm. This can result from surgical dissection, ISB needle manipulation, intraneural injection, excessive ISB injectate or irrigation, or nerve traction. Muscle weakness, often due to post-surgery immobility, is also attributed by physical therapists (34). Consequently, we cannot ascertain that this reduction in muscle strength is due solely to the influence of ISB with ropivacaine or bupivacaine, although it is significantly documented.

5.3. Recommendations

Study the younger age group separately and with larger sample sizes to determine whether there is a difference between ropivacaine and bupivacaine in terms of motor nerve block and the possibility of postoperative muscle weakness, which is greater with bupivacaine. Use ropivacaine as an ideal alternative agent and avoid bupivacaine, especially in middle-aged and elderly patients.