1. Background

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) are characterized by progressive loss of neuronal structure and function, leading to cognitive and behavioral impairments. Common pathological features include oxidative stress, chronic neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and dysregulation of programmed cell death pathways (1, 2). Among NDs, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent, marked by memory deficits, executive dysfunction, and hallmark pathological lesions such as amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex (3, 4).

Aluminum (Al), a naturally abundant element, has been linked to neurological disorders like AD and Parkinson's disease (PD) (5, 6). This connection is observed in individuals with high exposure levels under specific conditions, such as occupational poisoning from welding, residing near cement factories, or through dialysis encephalopathy (7, 8). Aluminum exposure can induce key clinical and pathological hallmarks of AD, including memory deficits, loss of cholinergic neurons, and the formation of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex (3). Additionally, aluminum disrupts multiple brain cell-signaling pathways by promoting oxidative stress and inflammation, characterized by increased accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), reduced endogenous antioxidants such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH), and activation of inflammatory cascades including TLR4/NF-κB and the NLRP3 inflammasome (9, 10). Subsequent NLRP3 activation leads to caspase-1 cleavage and gasdermin D (GSDMD)-mediated pyroptosis, ultimately contributing to neuronal death in AD models (11). Consequently, developing strategies to mitigate aluminum-induced damage represents a promising therapeutic approach for AD.

Pyroptosis is a lytic form of programmed cell death, characterized by plasma membrane rupture and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, amplifying neuroinflammation (12). Additionally, myeloperoxidase (MPO), expressed in infiltrated neutrophils, activated microglia, neurons, and astrocytes, catalyzes the production of hypochlorous acid (HOCl) and promotes ROS/RNS generation, exacerbating oxidative and inflammatory damage in neurodegeneration (13). Given its inflammatory nature, pyroptosis is now closely linked to the pathogenesis of AD. Research indicates that the activation of inflammasomes, which can stimulate pyroptosis, contributes to the onset of AD (14). Among the various inflammasomes, the NLRP3 inflammasome has been the subject of extensive investigation. Studies have established that NLRP3 has a crucial functional relationship with caspase-1 (15). In pathological conditions such as AD, the NLRP3 inflammasome activates caspase-1, which in turn triggers the pyroptotic pathway, ultimately leading to cell death. Consequently, the suppression of pyroptosis has been proposed as a potential neuroprotective strategy for preserving neurons in AD (16).

Methylphenidate (MPH) is a potent psychostimulant medication primarily recognized for its ability to promote wakefulness and enhance cognitive functions, securing its role in treating a range of disorders (17). The MPH is a psychostimulant that enhances cognitive function by inhibiting dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake (17, 18). Its most established application is as a first-line treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), where it effectively mitigates impulsivity and strengthens executive control, a set of high-level cognitive skills that includes working memory, mental flexibility, and planning (18-20). While clinically used for ADHD, preliminary evidence suggests MPH may improve apathy and motivational deficits in AD (21-23).

Melatonin (MEL, N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine), the primary hormone secreted by the pineal gland, is a crucial regulator of physiological processes such as circadian rhythms and body temperature (24). Beyond these roles, it exhibits potent therapeutic potential, particularly in AD, through its robust antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Research demonstrates that MEL directly counteracts oxidative stress by stimulating key antioxidant enzymes like SOD and GSH peroxidase in the brain, while also protecting these enzymes from damage (25, 26). These cellular and molecular improvements translate into significant cognitive recovery. Studies in AD mouse models confirm that MEL treatment effectively restores memory function (27). Its benefits extend to chronic administration, which has been shown to inhibit the formation of both amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, hallmark pathologies of AD (28, 29).

2. Objectives

Together, these findings provide a strong rationale for investigating the combined effects of MEL and MPH on aluminum-induced neurodegeneration, oxidative stress, NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis, and MPO activity as potential neuroprotective strategies in AD. The main focus is to elucidate the underlying mechanisms, including modulation of the pyroptosis pathway. It is anticipated that our findings will provide a solid scientific basis for a novel combination therapeutic strategy for AD and related neurological disorders.

3. Methods

Aluminum chloride hexahydrate (AlCl3·6H2O, Cat #: 1.01084.0250) was procured from Germany, SIGMA-ALDRICH. The MPH hydrochloride (Ritalin®) was procured from Novartis and MEL [MEL, powder, ≥ 98% (TLC) Cat #M5250] was from USA SIGMA-ALDRICH.

3.1. Animals and Experimental Groups

Male BALB/c mice (weight of 25 ± 30 grams, age of 6 - 8 weeks) (30) were randomly divided into six groups (n = 6 each group), including the healthy control group, which received distilled water and normal food for 15 days. The sham group received MPH (10 mg/kg) dissolved in distilled water and MEL (10 mg/kg) dissolved in distilled water and normal food for 15 days. Aluminum chloride (AlCl3) group animals received AlCl3 (300 mg/kg) dissolved in distilled water, administered orally for 15 days (30, 31). The AlCl3 + Mel, AlCl3 + MPH, and AlCl3 + Mel + MPH groups: In these groups, animals received AlCl3 (300 mg/kg) dissolved in distilled water administered orally for 15 days; after establishing the AlCl3-induced neurotoxicity models, AlCl3 administration was stopped and subsequently animals in groups 4, 5, and 6 received MEL (10 mg/kg), MPH (10 mg/kg), and a combination of MEL (10 mg/kg) and MPH (10 mg/kg) as oral solutions for 7 days. The doses for AlCl3 (22), MPH (31), and MEL (12, 32), Al- used are based on previous animal studies (33). Since the aim was to compare the effects of MPH and MEL, the parameter of treatment days had to be kept the same.

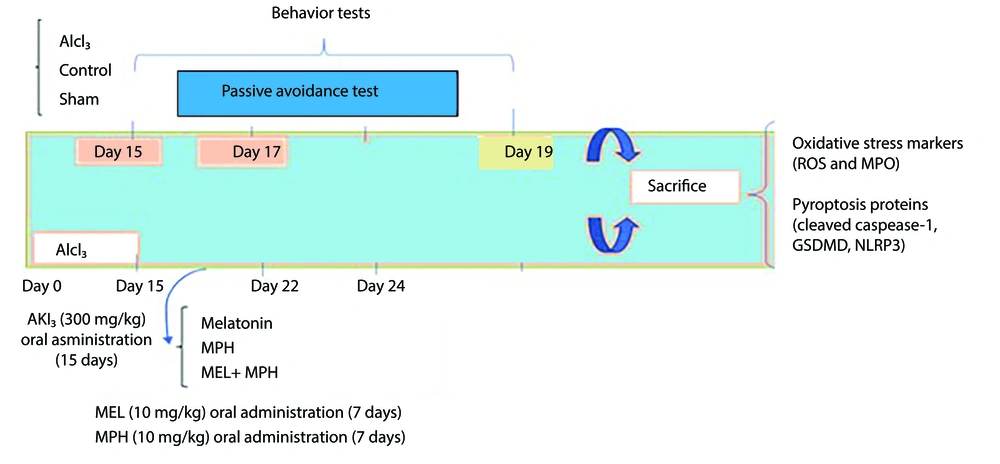

Animals were bred and maintained in the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) Laboratory Animal House. Mice were maintained in standard metal cages under standard conditions of constant temperature (25 ± 2°C) and a normal light-dark cycle (12 - 12 h). Laboratory animals were cared for and used according to protocols provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH No: 8023, 1978 revised). The experiment was approved by the TUMS Ethics and Research Committee (IR.TUMS.AEC.1401.166). Figure 1 shows a schematic timeline of the different stages of the study. Healthy male mice with normal activity and no visible abnormalities were included in the study. Mice showing signs of illness, lethargy, or failure to adapt to the experimental conditions were excluded prior to treatment initiation.

Timeline depicting 15-day aluminum chloride (AlCl3) treatment followed by oral administration of melatonin (MEL) and methylphenidate (MPH) for 7 days, behavioral testing, and decapitation of animals for further analysis (Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; MPO, myeloperoxidase; GSDMD, gasdermin D).

3.1.1. Sample Preparation

After the treatment was completed, behavioral tests were performed (n = 6), and then mice were sacrificed under ketamine anesthesia (150 mg/kg) and the brain was immediately removed, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and homogenized in cold RIPA buffer (pH = 7.4). This assay was conducted after centrifuging the supernatant (1,000 g, 4°C, 10 minutes). The resulting supernatant fraction was used for biochemical and molecular studies (n = 4), and its protein concentration was determined. Triplicate measurements were performed for all parameters. Figure 1 shows a schematic timeline of the different stages of the study.

3.2. Behavior Studies

3.2.1. Passive Avoidance Test

The behavioral apparatus consisted of a plexiglass box partitioned into light and dark compartments by a guillotine door. The dark compartment was equipped with a stainless-steel grid floor for delivering foot shocks on the first day. An adaptation trial was conducted. Each mouse was placed in the light compartment, and its latency to enter the dark compartment was recorded. Mice that did not cross within 60 seconds were excluded. This was followed by a training trial where, upon entry into the dark compartment, the guillotine door was closed and a foot shock (1.5 s, 1 mA, 50-Hz square wave) was delivered through the grid floor. The step-through latency (STL), defined as the time taken to place all four paws into the dark compartment, was measured. Mice were removed 30 s post-shock. After 24 hours, a retention test was performed identically to the training trial but without the foot shock. Both the STL and the total time spent in the dark compartment (TDC) were recorded up to a cutoff time of 300 seconds as measures of memory retention.

3.3. Studying Biochemistry

3.3.1. Oxidative Stress

Protein concentration was determined for each sample. The ROS are an array of derivatives of molecular oxygen that occur as a normal attribute of aerobic life. Elevated formation of the different ROS leads to molecular damage, denoted as ‘oxidative distress’. The ROS activity was measured using a special kit of assay (ROS, Karmania pars gene, LiveScience, Iran). The MPO is an enzyme directly involved in the oxidative-inflammatory process. The MPO was measured using a kit according to the manufacturer's guidelines (MPO, Lavand Lab Kit, LiveScience, Iran).

3.4. Studying Molecular

3.4.1. Western Blotting

Western blot analysis was conducted according to an established protocol (34). Briefly, tissue samples were lysed using RIPA buffer. The homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble debris, and the resulting supernatants were collected for further analysis. Total protein concentration was determined using a Bradford Protein Quantification kit (DB0017, DNAbioTech, Iran) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, lysates were combined with 2X Laemmli sample buffer, and 20 μg of protein per sample was heat-denatured and separated by SDS-PAGE. The resolved proteins were then transferred onto a 0.2 μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad, Cat. No: 162 017777). To prevent non-specific binding, the membrane was blocked for one hour with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Aldrich, Cat. No: A-7888) in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20). It was then incubated with the following primary antibodies for one hour at room temperature: Anti-cleaved caspase-1 (4199T, CellSignal), anti-GSDMD (39754S, CellSignal), and anti-NLRP3 (ab263899, Abcam). Following extensive washes with TBST, the membrane was probed with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (ab6721, Abcam). Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate with an exposure time of 1 - 2 minutes. β-Actin was used as a loading control for normalization. Densitometric analysis of the protein bands was performed using Gel analyzer software (Version 2010a, NIH, USA), whereby the area under the curve for each target protein band was normalized to that of its corresponding β-actin band. The resultant normalized values were then compared between experimental groups.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

All measurements were performed by an independent investigator blinded to the experimental conditions. The data were analyzed, and graphs were drawn using GraphPad Prism software 8.0. The passive avoidance test in groups was conducted using one-way ANOVA. We also used one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc to evaluate and compare oxidative stress and molecular tests in groups. Additionally, P < 0.05 was considered significant, and if significant, Tukey's post-hoc test was used. Data are expressed as Mean ± SEM.

4. Results

4.1. Neurobehavioral Observations

The effect of alone and combination of MEL and MPH on cognitive impairment induced by AlCl3 in mice with shuttle box task

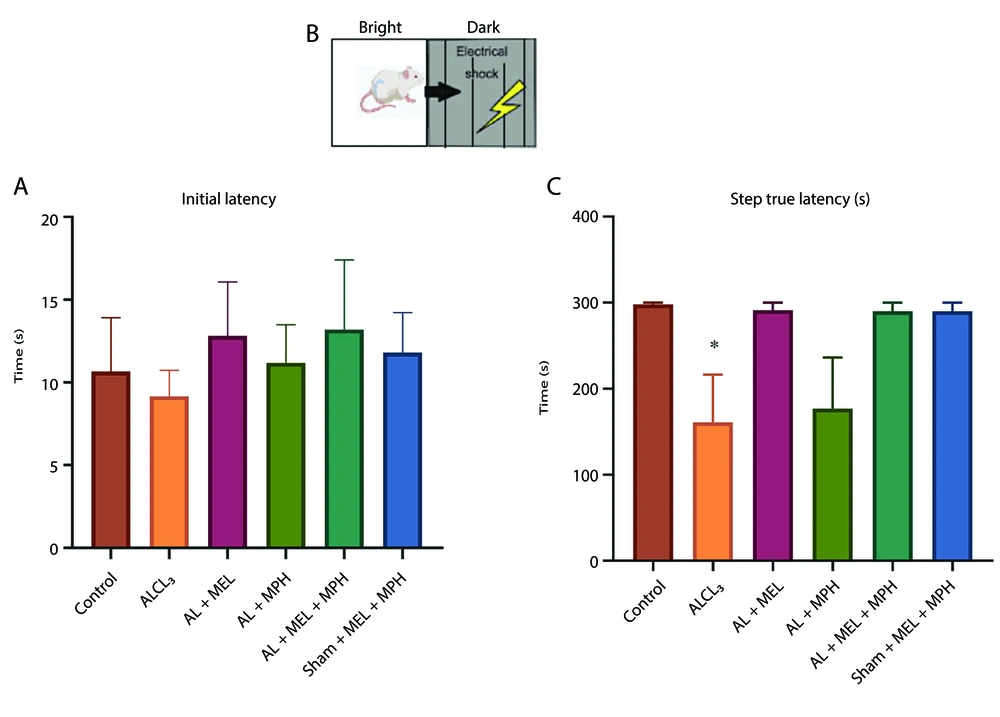

Figure 2A and C show the performance of mice in the passive avoidance test as determined by IL and STL. Regarding IL, one-way ANOVA analysis revealed no significant differences were found among the groups. Regarding STL, one-way ANOVA analysis revealed that there was a significant difference between the groups (F(5, 23) = 3.821; P = 0.011). In this respect, the AlCl3 group developed a significant impairment in retention and recall in the passive avoidance test relative to the control (P < 0.05). However, although MEL and MPH alone or in combination increased the latency of the animal to enter the dark room, this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2, n = 6).

Effects of methylphenidate (MPH) and melatonin (MEL) on learning and memory in aluminum chloride (AlCl3)-induced mouse models using the passive avoidance test: A, schematic of an apparatus shuttle box; B, the latency (s, mean ± SEM) of crossing from the light to the dark box prior to a foot shock (day 2); and C, the latency of crossing post-foot shock (day 3). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc was applied to analyze the data using GraphPad Prism (n = 6, * P < 0.05 in AlCl3-induced group compared to control).

4.2. Biochemical Experiments

4.2.1. The Effect of Alone and Combination of Melatonin and Methylphenidate on Oxidative Stress Induced by Aluminum Chloride in Mice

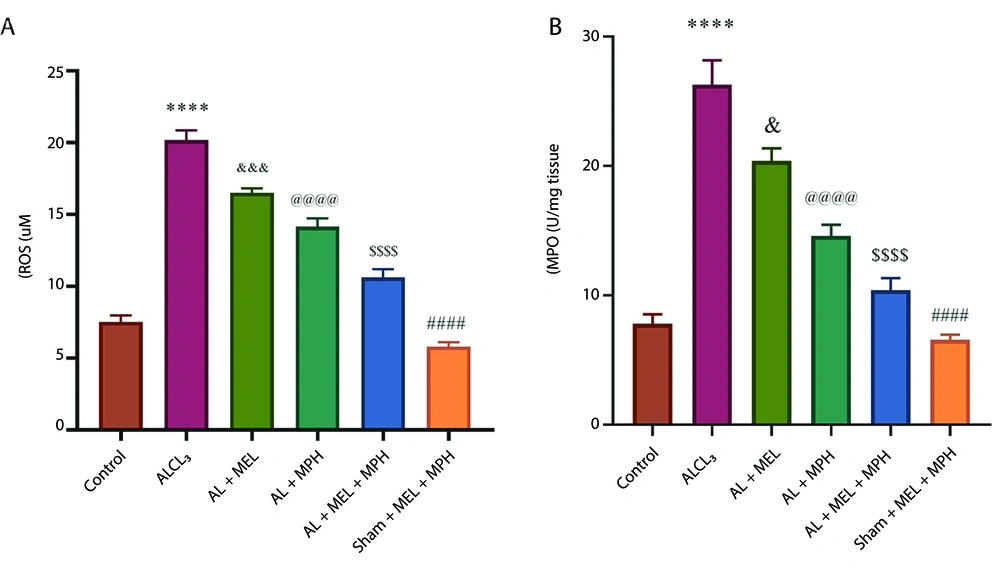

Figure 3 shows the changes in the activities of antioxidant systems, ROS, and MPO in hippocampal tissue in the experimental groups. One-way ANOVA analysis revealed significant differences in the ROS production and MPO activation among the groups (F(5, 18) = 120.5; P < 0.0001 for ROS; F(5, 18) = 53.23; P < 0.0001 for MPO; n = 4). Post-hoc Tukey's analyses indicated a significant increase in ROS production and MPO enzyme activity in the AlCl3 group compared to the control and Sham+ Mel+ MPH groups (P < 0.0001 for both ROS and MPO; Figure 3A and B). Moreover, our results revealed a significant reduction in ROS levels and MPO activity between MEL and Mel alone and Mel and MPH combined groups compared with the AlCl3 group (ROS: P < 0.001 for Mel, P < 0.0001 for MPH alone and combination of MEL and MPH; MPO: P < 0.05 for Mel, P < 0.0001 for MPH alone and combination of MEL and MPH).

A and B, changes in the activity of antioxidant enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in hippocampus tissues in experimental groups. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc was applied to analyze the data using GraphPad Prism (n = 4; **** P < 0.0001, #### P < 0.0001, & P < 0.05, &&& P < 0.001, @@@@ P < 0.0001, and $$$$ P < 0.0001; abbreviations: AlCl3, aluminum chloride; MPH, methylphenidate).

4.3. Molecular Experiments

4.3.1. The Effect of Alone and Combination of Melatonin and Methylphenidate on Apoptosis Markers Levels in Brain Tissues Induced by Aluminum Chloride in Mice

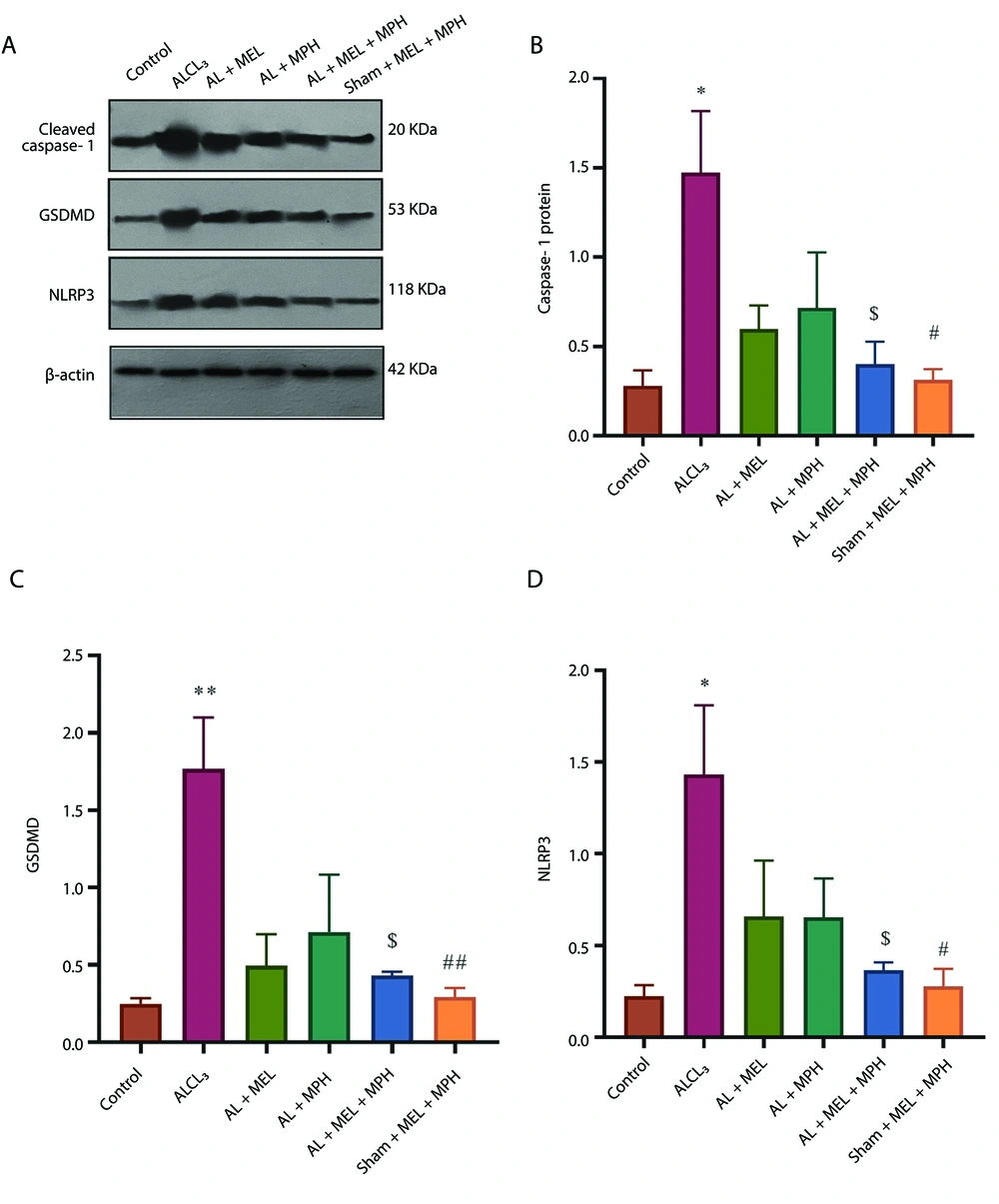

Figure 4A - D shows the expression of pyroptosis proteins (cleaved caspase-1, GSDMD, and NLRP3) levels (as key proteins involved in composing the inflammasome complex) in the hippocampus in the experimental group. One-way ANOVA analysis revealed significant differences in cleaved caspase-1, GSDMD, and NLRP3 among the groups (F(5, 12) = 4.60; P < 0.01 for cleaved caspase-1; F(5, 12) = 6.57; P < 0.003 for GSDMD, and F(5, 12) = 4.04; P < 0.022 for NLRP3). Post-hoc Tukey's analyses indicated a significantly increased level of caspase-1, GSDMD, and NLRP3 in the AlCl3 group compared to the control and sham drug group (P < 0.05 for caspase-1, P < 0.01 for GSDMD, and P < 0.05 for NLRP3 in both control and sham drug). Post-hoc Tukey's analyses indicated that treatment with combined MEL and MPH resulted in a decrease in caspase-1, GSDMD, and NLRP3 protein levels compared to the AlCl3 group (P < 0.05 for all three proteins; n = 3). These results indicated that AlCl3 increased the levels of pyroptosis proteins, and combining MEL and MPH could have an inhibitory effect on the pyroptosis process.

Effects of methylphenidate (MPH) and melatonin (MEL) on markers of aluminum chloride (AlCl3)-induced pyroptosis in mouse models; A, the expression of pyroptosis proteins; B, cleaved caspase-1; C, GASDMD protein; and D, NLRP3 in the hippocampus in the experimental group. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test (mean ± SEM) was used for analysis. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (n = 3; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, and $ P < 0.05; abbreviation: GSDMD, gasdermin D).

5. Discussion

Based on the rationale that combination therapy can simultaneously target multiple disease pathways, this study investigated the synergistic potential of MEL and MPH against aluminum-induced neurotoxicity. The MEL was used for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, while MPH was employed to enhance neuronal capacity. This dual strategy aimed to inhibit pyroptosis as programmed cell death and promote neuroprotection jointly. In the present study, we show that chronic administration of AlCl3 in the drinking water of animals for 15 days caused significant impairments in learning and memory, increased oxidative stress, and induced pyroptosis-induced cell death in the hippocampus.

In our study, AlCl3 increased oxidative stress in hippocampal neurons, as evidenced by elevated ROS production and MPO activity, leading to neurotoxicity and impaired cognitive function. These findings are consistent with those of Malik et al. and Amber et al., both of which indicate that aluminum induces cognitive deficits through oxidative stress and inflammation, and that appropriate therapeutic interventions can attenuate these effects (31, 35). Our biochemical findings demonstrated that AlCl3 increased ROS production and MPO activity, indicating enhanced oxidative stress and microglial activation. These results are consistent with previous reports by Skalny et al., and Cheng et al., which highlight the role of aluminum accumulation in stimulating ROS production, inducing inflammatory pathways, and causing mitochondrial dysfunction — particularly impairments in the electron transport chain and reduced mitochondrial membrane potential. Moreover, aluminum exposure was associated with decreased activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, and GPx, reduced GSH levels, and activation of inflammatory and apoptotic pathways, including NF‑κB and the NLRP3 inflammasome, ultimately leading to neuroinflammation, neuronal damage, and exacerbation of injury related to NDs (36, 37). Treatment with MEL, MPH, or a combination of MEL and MPH exerted antioxidant effects and reduced AlCl3-induced oxidative stress.

Furthermore, analysis of the pyroptosis pathway revealed that AlCl3 increased the expression of key proteins, including caspase-1, GASDMD, and NLRP3, leading to hippocampal cell death. This cellular damage was associated with the observed cognitive deficits. However, the combination of MEL and MPH (without either of them) reduced the expression of these inflammatory complex proteins, thereby suppressing pyroptosis.

Despite extensive research efforts, effective strategies for the prevention of AD, a neurodegenerative disorder, remain elusive due to the unclear understanding of its underlying molecular mechanisms (38). In the present study, our results provide new insights into therapeutic approaches for AD by demonstrating the potential of this combination therapy to reduce oxidative stress and alleviate cognitive impairment. The findings of this study are consistent with previous findings supporting the synergistic effect of MPH with other compounds and drugs in AD. Our results confirm that MEL inhibits the NLRP3-caspase-1-GSDMD pathway and improves cognitive function by reducing pyroptosis-type neuronal death. Supporting this, a study by Saha et al. demonstrated that MEL can inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a mouse model. By modulating the TLR4/NF-κB and P2X7R signaling pathways, MEL reduced inflammation, attenuated liver tissue damage, and lowered levels of inflammatory cytokines. These findings suggest that MEL may exert a protective effect in conditions associated with oxidative stress and chronic inflammation by suppressing key inflammatory pathways and mitigating hyperactive immune responses. Similarly, Chitimus et al. reported that MEL, due to its potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, can reprogram cellular and molecular responses linked to oxidative stress and inflammation. By inhibiting ROS production, reducing inflammatory cytokine levels, and regulating signaling pathways such as NF-κB and NLRP3, MEL helps maintain cellular homeostasis and may contribute to the prevention and treatment of diseases associated with inflammation and oxidative damage (39, 40).

Although the drug MPH improves cognitive function and mental flexibility by modulating the dopamine and noradrenaline systems, it exhibits dual effects under neurotoxic conditions. Chronic use of MPH can increase oxidative stress. However, a study by Sanches et al., showed that the effect of MPH is highly dependent on environmental conditions: In a healthy state it may be harmful, but in conditions of inflammatory stress it can be beneficial and enhance antioxidant defenses, reduce oxidative stress, lower intracellular calcium levels, and improve mitochondrial structure and function (41). In a study by Comim et al., it was found that MPH treatment in an animal model of ADHD caused increased oxidative stress and changes in cellular energy metabolism. These findings emphasize that although MPH can improve cognitive and behavioral symptoms, long-term use may cause oxidative damage and cellular energy disruption. In rodent studies, MPH doses between 1 and 20 mg/kg/day are generally considered low to moderate, while doses above 20 mg/kg/day are associated with a higher risk of oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. The 10 mg/kg/day dose used in our study falls within this low to moderate range and has been shown to exert cognitive and neurochemical effects without causing severe oxidative damage. However, coadministration of MEL with MPH attenuated these deleterious effects, indicating the ability of MEL to counteract the stress-inducing and inflammatory effects of MPH. This suggests a synergistic protective interaction between MEL and MPH. Khalid et al. also showed that the combination of MPH with rosemary can improve cognition, regulate inflammation, and increase hippocampal neuronal density in a model of AlCl3-induced neurotoxicity (22, 42). In line with these results, the findings of the present study also suggest that the combination of MEL and MPH can be proposed as a novel therapeutic approach to balance oxidative and inflammatory processes in the brain.

Inflammasome complex activation led to caspase-1 cleavage and the induction of GSDMD protein, resulting in neuronal pyroptosis (inflammatory cell death). In addition, the elevated MPO levels in the aluminum-treated group indicated microglial activation and enhanced oxidative and inflammatory responses in brain tissue. These findings are consistent with the studies by Hao et al., which collectively demonstrated that aluminum exposure induces severe central nervous system damage primarily through activation of the NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis pathway. Both studies reported that aluminum triggers inflammatory neuronal death by increasing oxidative stress, activating the NLRP3 inflammasome, elevating caspase-1 expression, promoting GSDMD cleavage, and stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18. Overall, these investigations highlight NLRP3-dependent signaling — particularly the DDX3X–NLRP3 axis — as a key mechanism underlying aluminum-induced neurotoxicity and a potential therapeutic target in NDs. This is also consistent with evidence identifying aluminum accumulation as a cause of mitochondrial dysfunction and the activation of inflammatory pathways (43, 44).

The MEL treatment significantly reduced indices of oxidative stress and inflammation. With its potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, MEL exerts protective effects by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation, reducing ROS generation, and suppressing the caspase-1/GSDMD pathway. The decreased MPO activity observed in MEL-treated groups further indicates a reduction in oxidative damage associated with inflammatory responses.

The findings of the present study are consistent with those reported by Hardeland, who demonstrated that MEL exerts broad anti-inflammatory actions primarily through inhibition of NF-κB signaling, reduction of ROS production, and modulation of cytokine levels. Similarly, the study by Zhang et al. highlighted the neuroprotective capacity of MEL in spinal cord injury. They showed that MEL mitigates oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions, prevents neuronal cell death, and promotes neural tissue repair. Moreover, by improving mitochondrial function and reducing mitochondrial membrane permeability, MEL enhances neuronal survival and contributes to improved motor outcomes.

Taken together, these findings — along with the results of previous studies — indicate that MEL is a promising therapeutic agent for neuroprotection under injury conditions. By targeting the NF-κB/NLRP3 axis and enhancing mitochondrial function, MEL effectively suppresses the ROS-NLRP3-caspase-1-GSDMD cascade, thereby preventing neuronal death and exerting its neuroprotective role (45, 46). Therefore, MEL prevents neuronal death by inhibiting the ROS-NLRP3-caspase-1-GSDMD cascade and plays its neuroprotective role.

In the present study, the effects of MEL and MPH on an AlCl3-induced Alzheimer's model in mice were investigated. The study focused on the NLRP3, caspase-1, GSDMD, ROS, and MPO pathways. The results showed that chronic exposure to AlCl3 increased oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neuronal damage; a finding that is consistent with previous reports of the neurotoxic role of aluminum and its ability to induce cognitive and inflammatory abnormalities in animal models (43, 44). Collectively, our results indicate that AlCl3-induced neurotoxicity is mediated through ROS-dependent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1/GSDMD signaling, leading to pyroptotic neuronal death. The MEL effectively attenuates these effects by reducing ROS, MPO activity, and inflammasome activation. When combined with MPH, MEL mitigates MPH-induced oxidative stress, resulting in improved neuronal survival and cognitive performance.

Despite extensive research efforts, effective strategies for preventing AD — a progressive neurodegenerative disorder — remain elusive due to the incomplete understanding of its underlying molecular mechanisms. The novelty of the present study lies in demonstrating, for the first time, the synergistic effects of MEL and MPH in an AlCl3-induced Alzheimer’s model. While previous studies have not primarily focused on investigating MEL and MPH in combination, our study uniquely evaluates their combined impact on oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and cognitive outcomes.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the combination of MEL and MPH effectively mitigates cognitive deficits, reduces oxidative stress, and alleviates neuroinflammation and pyroptosis in an AlCl3-induced model of AD. These findings suggest that this combination therapy holds significant potential as a novel therapeutic approach for AD. By addressing multiple pathological mechanisms, MEL and MPH offer a promising strategy to combat the multifactorial nature of NDs. Further research is warranted to translate these findings into clinical applications.