1. Context

Radiologic imaging plays a crucial role in the diagnosis, severity assessment, and monitoring of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Imaging is essential for distinguishing these conditions, given their overlapping clinical presentations.

The COVID-19, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first identified in late 2019 and led to a global pandemic. While adults — especially the elderly and those with comorbidities — were most affected, the disease typically presented with a milder course in children, although severe pneumonia could occur (1, 2). Children may also play a significant role in viral transmission (3). The wide spectrum of findings and outcomes observed in pediatric COVID-19 cases contributes to ongoing uncertainty regarding the pandemic's impact on the pediatric population (4).

Most pediatric COVID-19 cases are asymptomatic or mild, presenting with fever, cough, fatigue, and gastrointestinal symptoms (5, 6). Severe illness progressing to respiratory failure and shock is rare but possible, particularly in children with comorbidities such as obesity, congenital heart disease, or immunosuppression (7-10). Fungal co-infections, such as Mucor spp., have been reported in some pediatric intensive care unit (ICU) cases (11). Overall, the prognosis is excellent, with most children recovering within one to two weeks (12).

The MIS-C emerged later in the pandemic, resembling Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome (13, 14). It is strongly associated with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection (15). Diagnostic criteria include fever, multi-organ involvement, elevated inflammatory markers, and the exclusion of other infections. Severe cases may require intensive care (16-18). Although most children recover, rare fatalities have been reported (16).

Diagnosing both conditions can be challenging due to their nonspecific symptoms. Radiology is a key tool for differentiation, particularly in critically ill children or those with known virus exposure (19). This review compares the imaging features of acute COVID-19 pneumonia and MIS-C in pediatric patients.

2. Methodology

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles published from January 2020 to December 2023. The search used the following keywords: (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2) AND (MIS-C OR "multisystem inflammatory syndrome") AND (children OR pediatric) AND [imaging OR radiology OR "chest X-ray" OR computed tomography (CT) OR ultrasound (US)]. Included studies focused on pediatric patients and reported radiologic findings of COVID-19 or MIS-C, and were published in English.

3. Imaging Results of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Children

Chest X-ray (CXR) is a common initial imaging modality, although most evidence is derived from CT. Lung US has demonstrated higher sensitivity than CXR and strong correlation with CT, offering a radiation-free alternative for detecting COVID-19 pneumonia in children (20).

Common CXR findings in pediatric COVID-19 include consolidation, ground-glass opacity (GGO), and peribronchial thickening (21-23). These opacities may be unilateral or bilateral, focal or diffuse, and peripheral or central (21, 22). Imaging findings in children are generally less frequent and less severe compared to adults (Table 1) (24, 25). Involvement of the lung bases is common, with no significant predilection for either the right or left side (21, 24, 26). These findings are nonspecific and overlap with those of other viral and bacterial pneumonias (27). Pleural effusions and lymphadenopathy are uncommon (21).

| COVID-19 Imaging Classification | Rationale | Adults CT Findings | Pediatric CT Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical appearance | Frequently observed CT findings of COVID-19 pneumonia include abnormalities with higher specificity. | (1) Peripheral, bilateral GGO with or without consolidation or visible intralobular lines (crazy paving); (2) multifocal GGO of rounded morphology with or without consolidation or visible intralobular lines (crazy paving); (3) reverse halo sign | (1) Bilateral peripheral and/or subpleural GGO and/or consolidation in lower lobe predominant pattern; (2) halo sign |

| Indeterminate appearance | Nonspecific CT findings of COVID-19 pneumonia | (1) Absence of typical features and presence of: Multifocal, diffuse, perihilar or unilateral GGO with or without consolidation lacking a specific distribution and are non- rounded or nonperipheral; (2) few very small GGO with a non-rounded and nonperipheral distribution | (1) Unilateral peripheral or peripheral and central GGO and/or consolidation; (2) bilateral peribronchial thickening and/or peribronchial opacities; (3) multifocal or diffuse GGO and/or consolidation without specific distribution; (4) crazy paving sign |

| Atypical appearance | Uncommon or not reported CT findings of pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia | (1) Absence of typical or indetrminate features and presence of: Isolated segmental or lobar consolidation without GGO; (2) smooth interlobular septal thickening; (3) discrete small nodules (centrilobular or tree in bud lung cavitation); (4) pleural effusion | (1) Unilateral segmental or lobar consolidation; (2) central unilateral or bilateral GGO and/or consolidation; (3) discrete small nodules (centrilobular or tree in bud); (4) lung cavitation; (5) lymphadenopathy; (6) pleural effusion |

| Negative | No findings suggestive of pneumonia | No CT findings suggestive of pneumonia | No CT findings suggestive of pneumonia |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CT, computed tomography; GGO, ground-glass opacity.

Chest CT studies in children are limited due to the lower incidence of severe disease. The CT can detect subtle abnormalities, but these often lack specificity and may not alter management (28). Common adult CT findings, such as bilateral GGO, consolidation, and the "crazy paving" pattern, are less frequent and less severe in children (25, 29, 30).

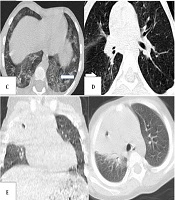

Typical pediatric CT patterns include peripherally located multifocal GGO and consolidation, predominantly in the lower lobes (Figures 1 and 2) (27, 29-35). Peribronchial thickening and tree-in-bud patterns are more common in children than in adults (29, 30, 33). Consolidation with a halo sign is frequent but must be distinguished from fungal infection in immunocompromised patients (29, 33, 35). The crazy paving and reverse halo signs are less common (29, 30, 32). Lobar consolidation without GGO, lymphadenopathy, or significant pleural effusions may indicate alternative diagnoses or bacterial superinfection (31, 32). Pulmonary embolism is rare in children (32, 36).

A, bilateral multifocal peripheral and round ground-glass opacities in a 12-year-old boy with fever and cough, typical for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); B, halo and reverse halo sign in a 12-year-old boy with a history of bone marrow transplantation and persistent fever (typical for COVID-19); C, crazy paving appearance in the left lower lobe (arrow) in a 6-year-old with fever and respiratory distress (typical for COVID-19); D, tree-in-bud appearance in the right lower lobe (arrow) in a 6-year-old boy (atypical for COVID-19); E, consolidation and cavitation in the right upper lobe in a 2-year-old girl with Gaucher disease and congenital neutropenia with respiratory symptoms (atypical for COVID-19).

4. Selection of the Appropriate Imaging Modality

Due to uncertainties regarding the availability and reliability of diagnostic tests in the early stages of the pandemic, imaging was considered a valuable tool for diagnosing acute COVID-19. However, even when children have a positive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test, imaging findings are frequently normal (28).

Imaging modality selection depends on clinical presentation and concerns about radiation exposure (22, 37). The severity of imaging findings correlates with clinical factors such as respiratory distress, ICU admission, and comorbidities (22, 32, 37, 38). The CXR is suitable for mild cases, despite its limited sensitivity, and is valuable for follow-up in cases of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) requiring ICU care (39).

Chest CT is preferred for severe cases to assess lung involvement, but its use must be balanced against the risks of radiation exposure and cost (31, 39, 40). In children, CT findings are often normal or mild, even in the presence of symptoms, making CT unreliable for confirming or excluding infection (40, 41). Decision-making should be guided by clinical findings and patient history, particularly comorbidities (39-42).

According to the American College of Radiology, imaging is usually unnecessary for well-appearing, immunocompetent children who do not require hospitalization (26). The CXR is the first step for hospitalized children, especially those with comorbidities or suspected hospital-acquired pneumonia (40). Chest CT is reserved for severe cases, alternative diagnoses, or complications (41, 42). Routine screening CT is not recommended due to radiation exposure.

5. Role of Lung Ultrasound

Lung US is a non-invasive, radiation-free modality ideal for real-time assessment of pulmonary status in children. It is highly accurate for diagnosing pneumonia, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax in the pediatric population (31, 39, 40).

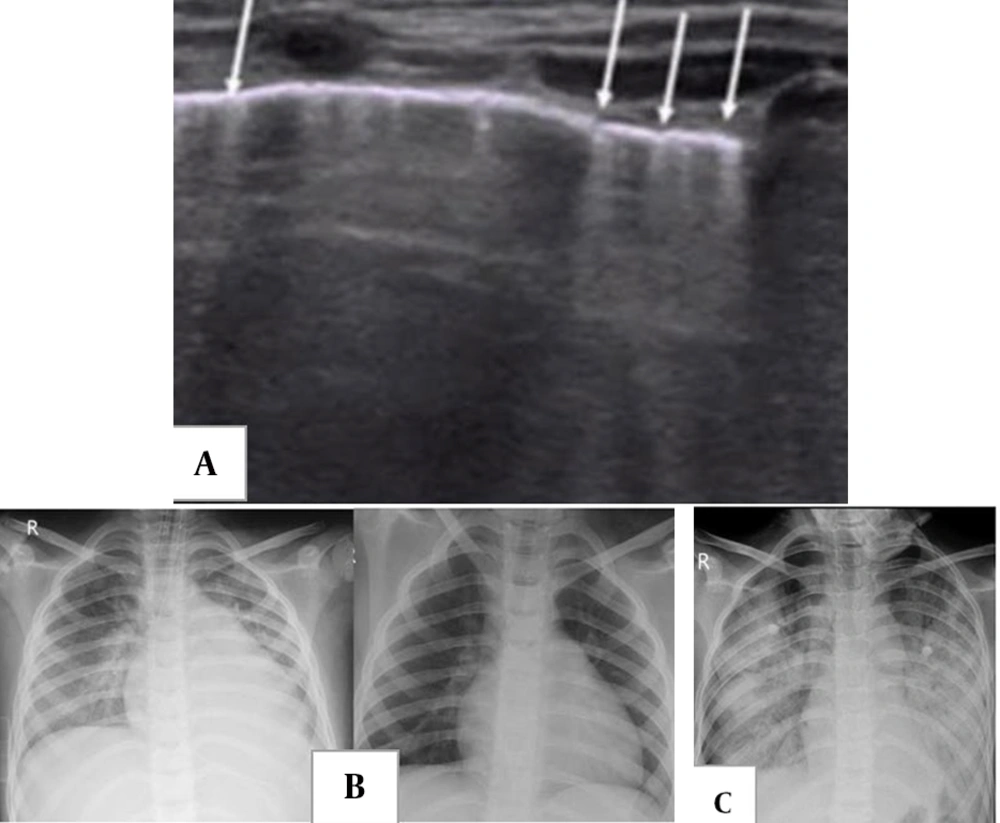

In adult COVID-19, lung US demonstrates B-lines and subpleural consolidations, often in the lower lobes (Figure 3A) (40). Pediatric COVID-19 cases show similar findings, indicating the utility of lung US, particularly given the typical peripheral lung involvement in children (26, 31, 42). However, the full role of lung US in pediatric COVID-19 requires further investigation (26).

A, two-week-old male full-term newborn with fever and mild respiratory symptoms; lung ultrasound (US) showed multiple vertical B-lines, from: Point-of-care lung US imaging in pediatric coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); B, a 7-year-old boy initially presented with fever and abdominal pain, progressing to respiratory distress and shock; serology was positive for COVID-19. Chest X-ray (CXR) shows features of cardiogenic pulmonary edema, including cardiomegaly, perihilar interstitial thickening and haziness, and mild bilateral pleural effusion. Ten days after treatment and symptom resolution, only cardiomegaly remains due to left heart failure. C, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in a 10-year-old boy with a diagnosis of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) with acute respiratory distress four weeks after acute COVID-19. Diffuse bilateral airspace consolidation is seen without cardiomegaly.

6. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Its Radiological Findings

Recently, an intriguing medical condition known as MIS-C has emerged. This syndrome is temporally associated with COVID-19, typically arising shortly after COVID-19 cases (13). Children diagnosed with MIS-C often have a history of direct contact with COVID-19 patients or evidence of present or prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, confirmed by positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or serologic tests (15). The MIS-C is characterized by hyperinflammation, multi-organ dysfunction, and a propensity for myocarditis, cardiorespiratory failure, and, rarely, death (43, 44).

While the radiographic findings of COVID-19 in children are well documented (45), imaging profiles of MIS-C remain limited (40). As research continues, further studies are needed to clarify the specific features of MIS-C in the pediatric population. Although pulmonary manifestations are uncommon in MIS-C, thoracic imaging findings differ from those observed in acute pediatric COVID-19 (17, 18). Nonetheless, radiological examinations are frequently performed in MIS-C due to rapid clinical deterioration. Identifying imaging abnormalities is crucial, as they correlate with severe conditions such as shock (15).

7. Pulmonary Imaging Findings in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children

The main thoracic imaging findings in MIS-C (Table 2) include heart failure, an ARDS pattern, and pulmonary embolism. These present as cardiomegaly, cardiogenic pulmonary edema, and pleural effusions secondary to acute heart failure (Figure 3B and C) (5, 21, 40, 46-48). Initial CXRs in MIS-C are often normal (16).

| Findings | MISC Associated with COVID-19 | Typical COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | Pulmonary edema; ARDS possible asymmetric | Peripherally located multifocal ground glass opacities and airspace consolidation, mainly in the lower lobes; halo sigh |

| Pleural | Pleural effusion | - |

| Cardiovascular | Heart failure; pericardial effusion; pulmonary emboli; coronary artery dilation | - |

| Extra thoracic | Mesenteric lymphadenopathy; ascites; hepatomegaly; echogenic renal parenchyma; gallbladder wall thickening | - |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Chest CT is rarely performed in MIS-C and is primarily reserved for specific clinical concerns such as sepsis or suspected pulmonary embolism (40, 46). Limited reports describe CT findings that mirror CXR patterns: Basal consolidation, GGO, interstitial changes, small pleural effusions, lymphadenopathy, and cardiomegaly (40). Rarely, pulmonary nodules have been reported (40, 42).

8. Abdominal Imaging Findings in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children

Abdominal imaging is often conducted as part of the diagnostic work-up before considering a diagnosis of MIS-C (42, 43, 49). Gastrointestinal symptoms are frequently the primary clinical manifestations of MIS-C and often closely resemble acute appendicitis (43). Common abdominal findings include right iliac fossa mesenteric inflammation, lymphadenopathy, terminal ileum/cecal wall thickening, ascites, hepatomegaly, and increased renal echogenicity (40, 42, 46, 50).

Differentiating MIS-C from appendicitis based solely on imaging can be challenging (40). Right lower quadrant changes may reflect abundant lymphoid tissue in Peyer’s patches (49). Therefore, it is essential to interpret these findings in the context of multiorgan involvement and to consider supporting laboratory data for accurate diagnosis.

Additional abdominal imaging findings in MIS-C include hepatosplenomegaly, periportal edema, hyperechogenic kidneys, splenic lesions or infarctions, ascites, gallbladder wall thickening or sludge, and urinary bladder wall thickening (40, 46, 47, 51). A rare case of post-COVID hepatic encephalopathy was diagnosed via CT (52).

9. Neurological Imaging Findings in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children

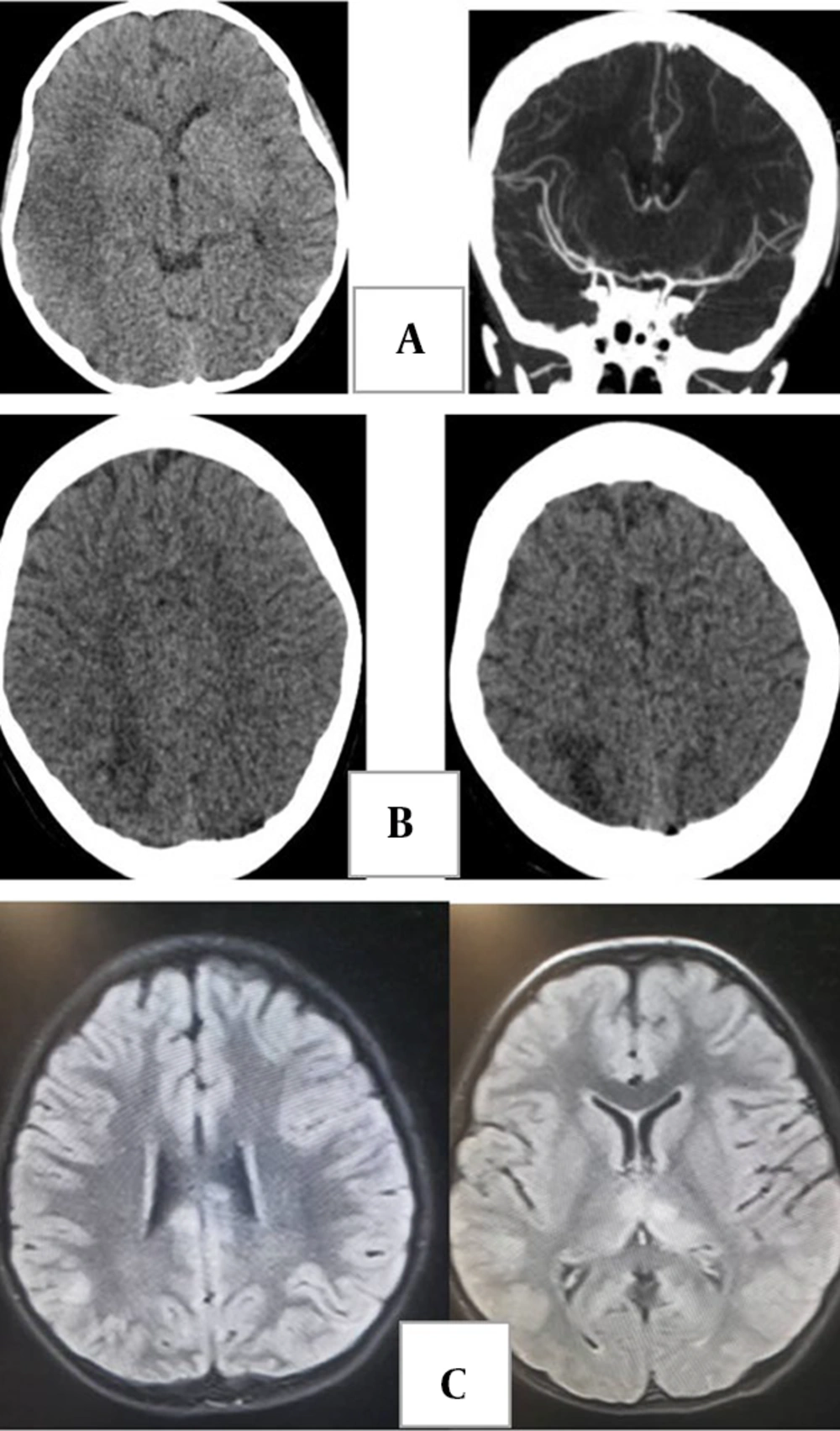

Cerebrovascular complications are less common in children than in adults. Ischemic stroke due to vasculitis is possible in MIS-C but is also a known complication of intravenous immunoglobulin treatment. Common neuroimaging patterns involve immune-mediated para-infectious processes affecting the brain, spine, and nerve roots (Figure 4A and B) (42, 47).

A, brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast and CT angiogram in a 7-year-old boy with a diagnosis of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) who presented with left hemiparesis. Images show hypodensity in the territory of the right middle cerebral artery (ischemic infarct). The CT angiogram shows duplicated middle cerebral artery on the right side as a variant. B, brain CT in a 12-year-old boy with a diagnosis of MIS-C who presented with headache and seizure during treatment, demonstrating asymmetric bilateral subcortical hypodensity in parieto-occipital lobes compatible with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. C, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) in an 8-year-old girl with recent history of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) who presents with loss of consciousness. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images show scattered abnormal signal in subcortical white matter and bilateral thalami.

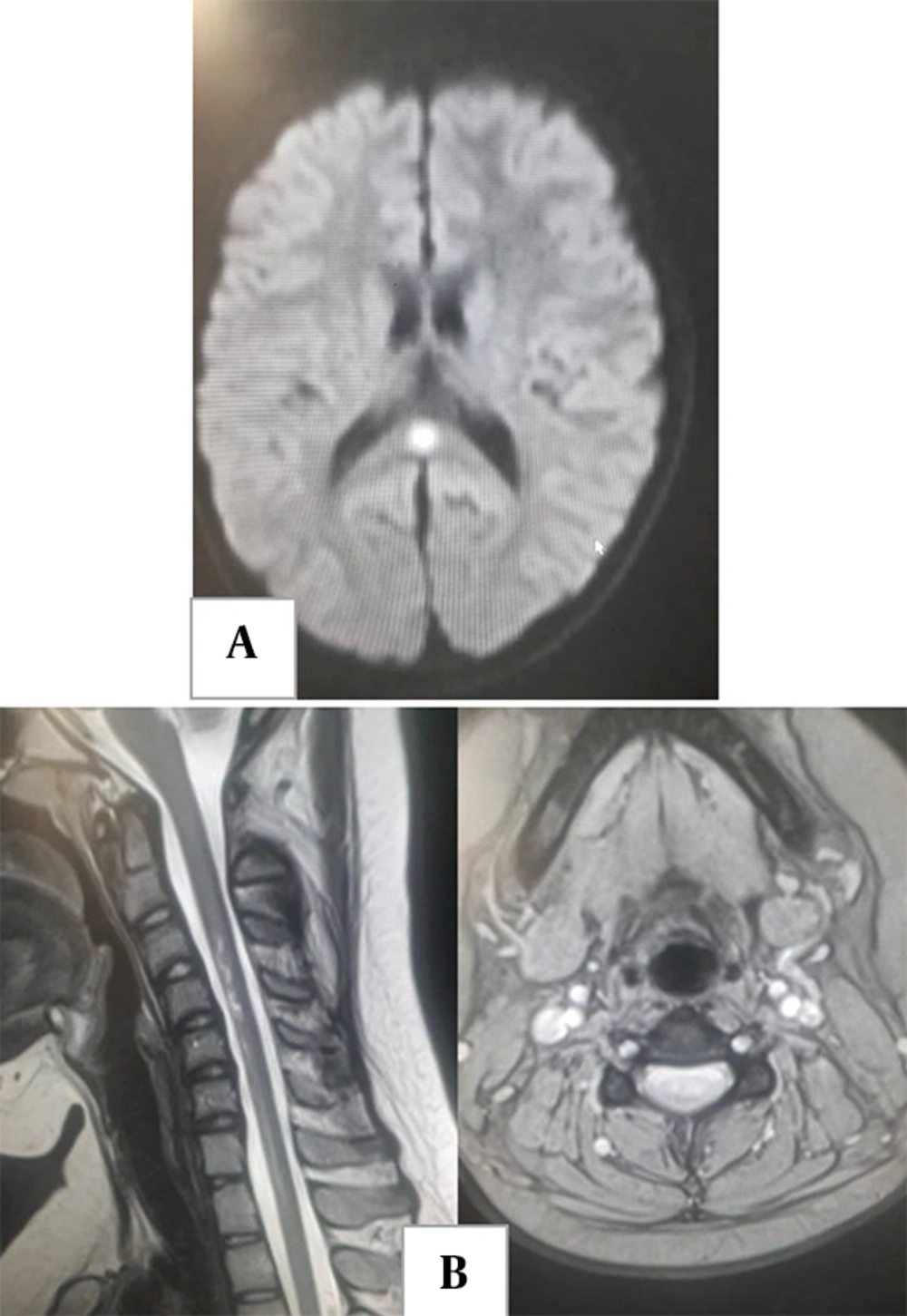

Typical brain manifestations include acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)-like appearances (Figures 4C and 5A), characterized by T2 hyperintense lesions in grey and white matter, sometimes with restricted diffusion or enhancement and occasionally resembling Guillain-Barre syndrome (42, 53, 54). Myelitis and neuritis are other potential presentations (Figure 5A and B) (55).

10. Radiological Considerations and the as Low as Reasonably Achievable Principle

The as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) principle is critical in pediatric imaging due to the heightened sensitivity of children to radiation. Key factors influencing dose include beam energy (kVp) and tube current (mA) (55, 56).

Replacing conventional CT with low-dose and ultra-low-dose protocols — especially with iterative reconstruction — significantly reduces exposure. Recommended low-dose settings are 90 kVp and 30 mAs for ages 0 - 6 years, and 90 kVp and 50 mAs for ages 6 - 12 years (56, 57).

11. Comparison of Radiographic Findings in Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children

The radiographic presentations of COVID-19 and MIS-C reflect distinct pathophysiologies: The COVID-19 is a direct viral pneumonia, while MIS-C is a post-infectious systemic vasculitis. Key differences are summarized in Table 2.

11.1. Pulmonary and Thoracic Findings

- The COVID-19: Findings are primarily parenchymal. The hallmarks are peripheral GGO and consolidation, often in the lower lobes. Pleural effusions, cardiomegaly, and lymphadenopathy are uncommon. Tree-in-bud and peribronchial thickening are more frequently seen in children.

- The MIS-C: Findings are often secondary to cardiac involvement. Typical features include cardiogenic pulmonary edema, cardiomegaly, and pleural effusions. Pure parenchymal GGO is not a primary feature. The ARDS can occur, often with cardiac dysfunction.

11.2. Cardiovascular Findings

- The COVID-19: Significant cardiovascular findings are rare.

- The MIS-C: Cardiovascular involvement is central. Imaging reveals pericardial effusion, coronary artery dilation, and impaired function. Pulmonary embolism is a recognized thrombotic complication.

11.3. Abdominal Findings

- The COVID-19: Abdominal imaging is not routinely performed, and specific findings are not characteristic.

- The MIS-C: Abdominal imaging is important due to frequent gastrointestinal symptoms. Key findings include mesenteric lymphadenopathy, ascites, ileitis or colitis (mimicking appendicitis), and hepatosplenomegaly.

11.4. Neurological Findings

- The COVID-19: Neurological complications are less common and findings are often nonspecific.

- The MIS-C: Neurological involvement can be severe. Characteristic patterns include ADEM-like appearances, myelitis, and neuritis.

12. Conclusions

In pediatric COVID-19, RT-PCR remains the primary diagnostic tool. The CXR is used for clinical follow-up in severe illness. Chest CT should be reserved for severe cases, with careful consideration of radiation exposure. Lung US is a promising, non-ionizing alternative, particularly for peripheral lung involvement, but requires further validation.

The MIS-C presents with distinct imaging findings, especially cardiovascular (cardiomegaly, effusions), abdominal (lymphadenopathy, ascites), and neurological (ADEM, myelitis) features. Radiologists should be familiar with these patterns for early diagnosis.

The ALARA principle must guide imaging, employing low-dose CT protocols. Comparative studies confirm that pleural effusion and cardiomegaly are significantly more frequent in MIS-C than in COVID-19 pneumonia (for example, 35% versus less than 10% for effusion) (5). Cardiovascular involvement is prominent in MIS-C (greater than 50%) but rare in acute COVID-19.

13. Literature Search and Study Selection

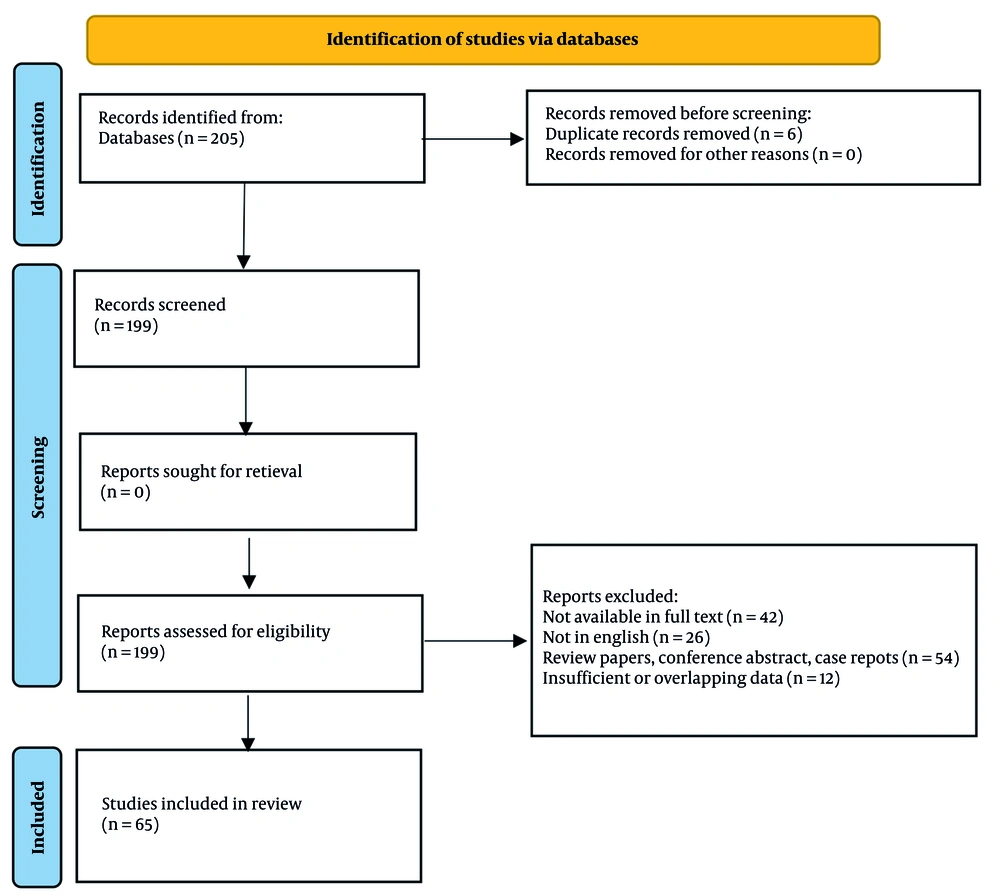

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar using relevant keywords and Medical Subject Headings for articles published up to 2023. A total of 205 records were identified. After removing 6 duplicates, 199 titles and abstracts were screened. Based on exclusion criteria (irrelevance, inappropriate study design, insufficient data), 135 records were excluded.

The remaining 64 full-text articles were assessed. Further exclusions were made for: Non-full text (n = 42), non-English language (n = 26), review papers, conference abstracts, and case reports (n = 54), and insufficient or overlapping data (n = 12). Ultimately, 64 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The selection process is summarized in Figure 6.

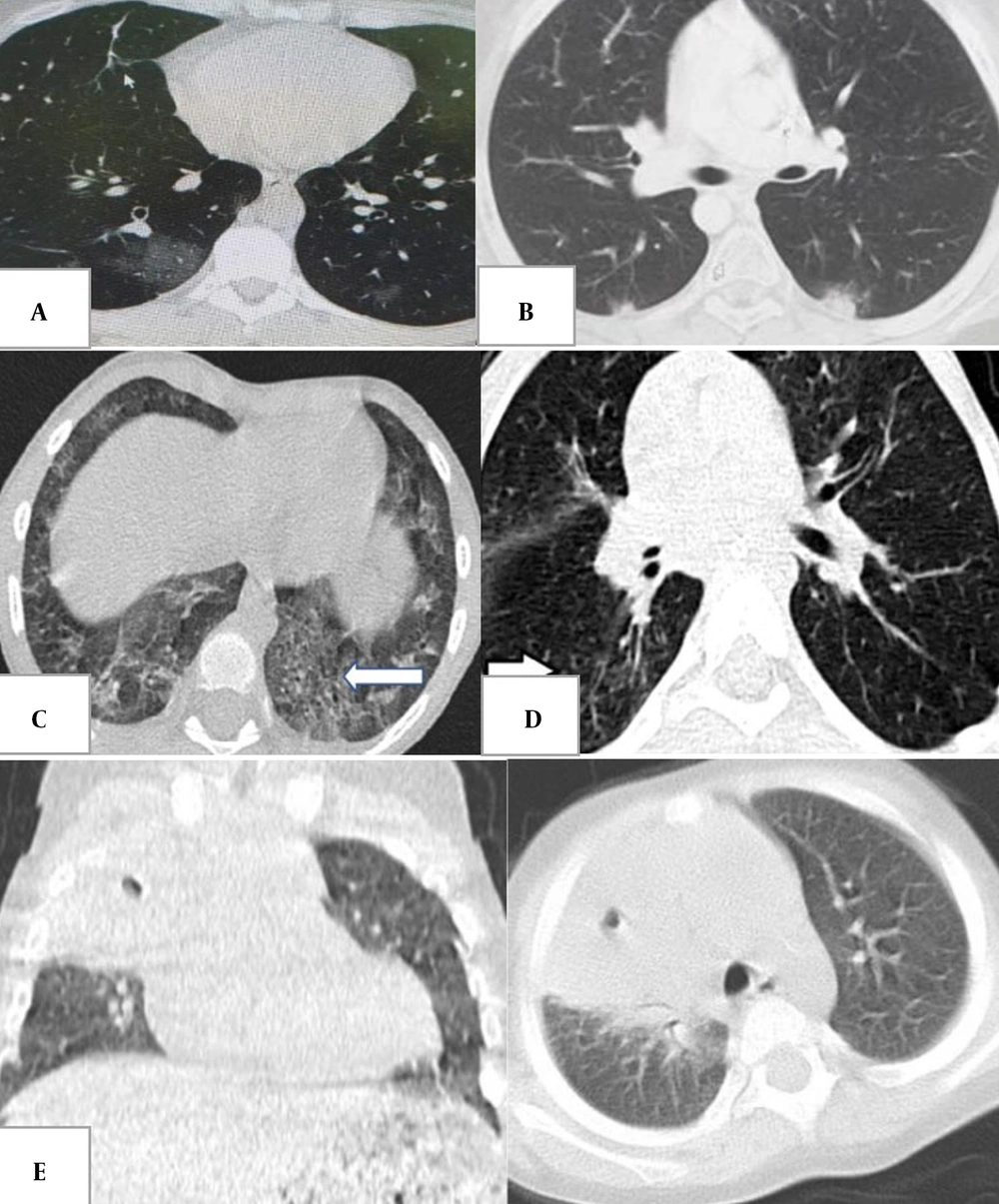

![A, centrilobular nodules in a 5-year-old boy with abdominal pain [atypical for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)]; B, segmental consolidation and pleural effusion in an 11-year-old boy with flank pain and cough (atypical for COVID-19). A, centrilobular nodules in a 5-year-old boy with abdominal pain [atypical for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)]; B, segmental consolidation and pleural effusion in an 11-year-old boy with flank pain and cough (atypical for COVID-19).](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/72f4fab98e3f54fc099fd868adba87f7bf14a760/apid-14-2-146685-g002-preview.webp)