1. Background

Pneumonia is one of the most important causes of mortality in children less than five years of age and the leading cause of death after the neonatal period. Among 10% of patients, it can be severe and require hospital admission (1). Lower age, prolonged fever before admission, HIV infection, malnutrition, varicella infection, cyanosis, and grunting are factors that increase the risk of pneumonia complications (2, 3). Parapneumonic pleural effusion (PPE) is the most common complication of pneumonia that may progress to empyema. Other complications of pneumonia include pneumothorax, lung abscess, and pneumatocele (4). Empyema is the accumulation of thick fluid and pus within the pleural space and mostly occurs as a consequence of pneumonia (5). Indeed, empyema occurs in 0.6% of children admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and increases the length of hospital stay (LOS), requiring intensive care unit admission (6). Empyema should be suspected if the fever does not subside after 48 hours of antibiotic therapy for a patient with pneumonia (7). Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of pediatric empyema, and Staphylococcus aureus is the second most common cause, being more prevalent in Africa and Asia (3).

The PPE progression to empyema includes three continuous stages. The first stage, or exudative stage, involves the accumulation of culture-negative fluid in the pleural space. If appropriate treatment is not received, it progresses to the subsequent stage, which is the fibrinopurulent stage. In this stage, the fluid becomes suppurative and advances to a loculated fluid. In the third stage, fibroblasts infiltrate the pleura, increasing their thickness, and subsequently, fibrous formation occurs, causing lung dysfunction (5). Severe malnutrition, immune deficiency, poverty, and incomplete vaccination are among the factors associated with empyema, but empyema mostly occurs secondary to delayed or inappropriate treatment (8). Early diagnosis and treatment of empyema are very important to prevent complications such as bronchopleural fistula and lung dysfunction (9).

There are several different treatment approaches for pediatric empyema. However, their cost-benefits are yet to be determined and compared. For example, antibiotic therapy without fluid drainage is effective and safe in the early stages of PPE, but about 10% of patients require drainage of the effusion. Chest tube placement with or without fibrinolytic administration is the most common technique for drainage. Patients without improvement with these common treatments require surgical techniques, including video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and open thoracotomy (5). Despite the increasing incidence of empyema in some studies, research is limited in the pediatric group, and there is a lack of agreement on the best approach to pediatric empyema (7, 10).

2. Objectives

The pediatric population is an age group in which empyema is associated with relatively high mortality rates. Therefore, it is crucial to produce more evidence on the costs and benefits of different therapeutic measures to establish precise and targeted treatment guidelines for pediatric empyema. However, limited studies have been conducted in this regard in Iran, and among previous ones, none have compared multiple treatment options. Hence, the present study aimed to compare the effectiveness and outcomes of different treatment methods for pediatric empyema in addition to evaluating demographic, clinical, and paraclinical findings in children with PPE and empyema.

3. Methods

In this retrospective cross-sectional study, 97 patients were included. The inclusion criteria were the age range of 1 month to 18 years, diagnosed with PPE or empyema, and admitted to the pediatric surgery, pulmonary, and infectious disease departments in the Mofid tertiary referral pediatric hospital (Tehran, Iran) from March 2016 to February 2022. The exclusion criterion was having an empyema secondary to causes other than pneumonia. Data collected included age, gender, comorbidity, length of symptoms before admission, prehospital antibiotic therapy, clinical symptoms and signs, laboratory findings [complete blood count and differentiation (CBC-diff), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), pleural fluid culture], imaging findings, antibiotic therapy during hospitalization, and initial treatment within the first seven days of admission and their outcomes.

Regarding comorbidities, without stratifying the findings based on them, only the presence of one or more conditions, including cystic fibrosis, prematurity, seizure, immune deficiency, and asthma, was considered a positive comorbid finding in the patient history. Patients were divided into four groups based on the initial treatment done within the first week of admission. Antibiotic therapy was initiated for all patients. This was obtained from a pooled dataset, but it was evident that the patients received their treatments based on disease severity and initial physician preferences. In brief, the general approach was that patients not responding to more conservative treatments underwent less conservative treatments in the next steps. The groups were defined as follows: The first group, patients who received antibiotics only; the second group, patients who had chest tubes without fibrinolytic; the third group, patients who had chest tubes with fibrinolytic administration; and the fourth group, the surgery group (VATS or open thoracotomy).

Outcome measures, including remission after initial treatment, LOS (4), length of fever (LOF) during hospitalization, complications, readmission, and mortality rate, were compared between groups. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25. Categorical variables were reported in frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations. The LOS and LOF frequencies were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests among patients with and without comorbidity. The Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests were chosen because the data did not meet the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances required for parametric tests. The Kruskal-Wallis test, a non-parametric method, is used for comparing more than two independent groups, making it suitable for analyzing the differences in LOS and LOF across multiple patient groups. The Mann-Whitney test is another non-parametric test appropriate for comparing two independent groups, thus aiding in the comparison of LOS and LOF between patients with and without comorbidities. A chi-squared test was performed to compare categorical variable frequencies among the four study groups. The chi-squared test was chosen because it is specifically designed to examine the association between categorical variables in different groups, allowing us to determine if there are statistically significant differences in the frequencies of categorical variables among the study groups. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Patients’ Conditions Before Admission

Among the 97 patients included in this study, 50 were male and 47 were female. The mean age was 5.48 ± 3.79 years (ranging from 1 month to 17.25 years). Among them, 26 (26.8%) patients had comorbid conditions, with a history of seizure being the most common comorbidity (i.e., four children). The mean length of symptoms before admission was 13.14 ± 8.77 days. The most common signs at admission were decreased breathing sounds in 79 (81.4%), crackles in 42 (43.3%), and tachypnea in 35 (36.1%) patients. Fever in 91 (93.8%) and cough in 84 (86.6%) patients were the most common symptoms. Some patients had received antibiotics before admission, with vancomycin (25.8%), azithromycin (24.7%), and ceftriaxone (15.5%) being the most commonly administered antibiotics. Blood and pleural fluid samples were collected from the patients at the time of admission. Laboratory findings showed leukocytosis and increased inflammatory markers in patients’ blood samples (Table 1). The pleural fluid culture was negative in most samples (78.4%), and among the culture-positive samples, the most common isolated microorganisms were S. pneumoniae (3.1%) and Acinetobacter species (3.1%) (Table 2). Regarding chest involvement assessed by chest X-ray, all participants (100%) had pleural effusion, with the right side of the chest involved in 43 (44.3%) patients, the left side in 42 (43.3%) patients, and bilateral chest involvement in 12 (12.4%) patients (Table 2). Additionally, atelectasis, alveolar infiltration, and loculated fluid were seen in 70.1%, 69.1%, and 67% of the patients, respectively.

| Variables | Range | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| ESR (mm/h) | 2.00 - 124.00 | 68.01 ± 27.73 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 5.00 - 177.00 | 64.36 ± 34.47 |

| WBC (per µL) | 2300.00 - 31400.00 | 14634.02 ± 5790.29 |

| Neutrophil % | 8.00 - 94.00 | 71.03 ± 15.96 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 5.50 - 14.90 | 10.06 ± 1.65 |

| PLT (per µL) | 26000.00 - 1431000.00 | 451752.57 ± 271888.19 |

Abbreviations: ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein.

| Chest Imaging Findings | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Pleural effusion | 97 (100) |

| Atelectasis | 68 (70.1) |

| Alveolar infiltration | 67 (69.1) |

| Loculated effusion | 65 (67) |

| Peri bronchial infiltration | 54 (55.7) |

| Thickened pleura | 46 (47.4) |

| Cavitation (necrotizing pneumonia) | 36 (37.1) |

| Pneumothorax | 34 (35.1) |

| Air bronchogram | 20 (20.6) |

| Para-tracheal lymphadenopathy | 19 (19.6) |

| Reticulonodular infiltration | 7 (7.2) |

| Lung abscess | 6 (6.2) |

| Tracheal/mediastinal shifting | 3 (3.1) |

| Microorganism | |

| Negative | 76 (78.4) |

| Pneumococcus | 3 (3.1) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 3 (3.1) |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 2 (2.1) |

| Pseudomonas | 2 (2.1) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (1) |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1 (1) |

| Klebsiella | 1 (1) |

| Nocardia | 1 (1) |

| Escherichia coli | 1 (1) |

| Not done | 6 (6.2) |

| Complications | |

| Subcutaneous emphysema | 27 (27.8) |

| Bronchopleural fistula | 4 (4.1) |

| Pneumothorax | 4 (4.1) |

| Surgical site infection | 1 (1) |

| Pneumatocele | 1 (1) |

4.2. Treatments and Outcomes

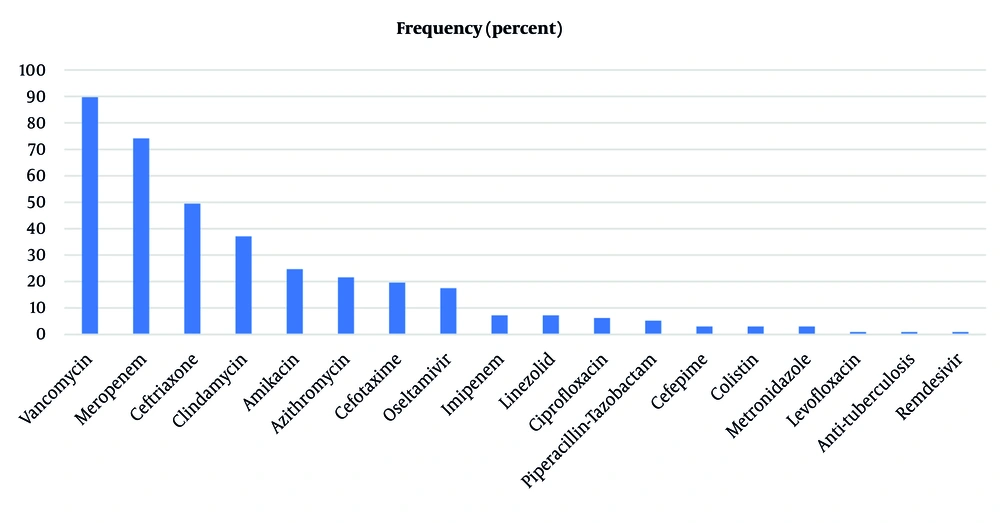

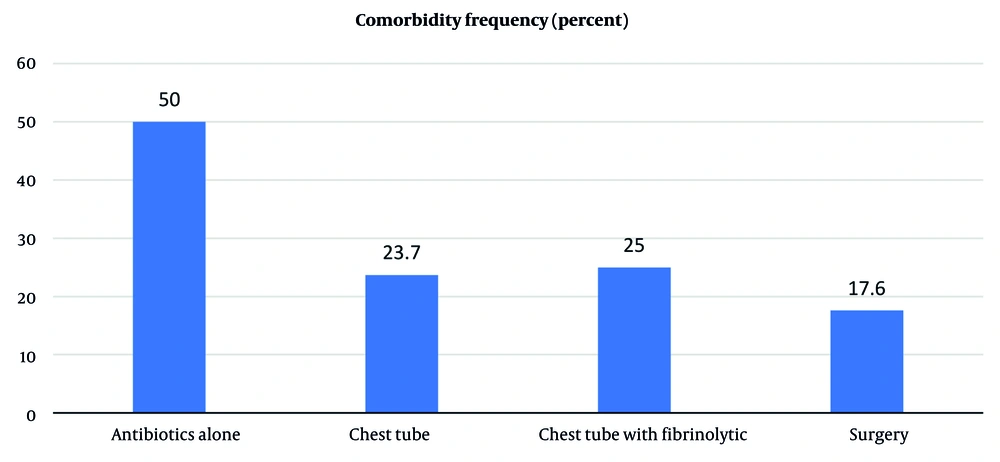

The initial treatment included antibiotics alone in 14 (14.4%) patients (i.e., group 1); chest tube placement in 38 (39.2%) patients (i.e., group 2); chest tube with fibrinolytic administration in 28 (28.9%) patients (i.e., group 3); open thoracotomy in 9 (9.3%) patients; and VATS in 8 (8.2%) patients (i.e., group 4). Among antibiotics, vancomycin (89.7%), meropenem (74.2%), and ceftriaxone (49.5%) were the most commonly administered during hospitalization for all patients (Figure 1). Remission after initial treatment was significantly different between the study groups (P = 0.011). The surgical group (group 4) had the highest rate of remission (94.1%), and the chest tube group (group 2) had the lowest rate of remission (52.6%). Among all study populations, 67 (69.1%) patients improved with initial treatment, and 30 (30.9%) patients eventually required surgery. There was no significant difference in mortality rate, complications, and readmission rates between groups, with subcutaneous emphysema being the most common complication (Table 3). Three patients expired secondary to severe sepsis and systemic complications, and three patients were readmitted within two weeks of discharge. However, these patients improved with antibiotic therapy at the second admission. The LOS and LOF during admission were also not significantly different between groups (Table 3).

| Variables | Interventions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 14): Antibiotic Alone | Group 2 (n = 38): Chest Tube | Group 3 (n = 28): Chest Tube with Fibrinolytic | Group 4 (n = 17): Surgery | P-Value | |

| Remission after initial treatment | 9 (64.3) | 20 (52.6) | 22 (78.6) | 16 (94.1) | 0.011 b |

| Mortality | 0 (0) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.9) | 0.498 |

| Complication | 1 (7.1) | 13 (34.2) | 12 (42.9) | 6 (35.3) | 0.137 |

| Readmission within two weeks | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 0.467 |

| LOF after admission | 6.50 ± 4.11 c | 8.50 ± 1.09 | 11.50 ± 1.24 | 6 ± 2.30 | 0.602 |

| LOS | 14.50 ± 4.16 c | 17.00 ± 1.37 | 19.00 ± 1.15 | 14.00 ± 2.29 | 0.193 |

Abbreviations: LOS, length of hospital stay; LOF, length of fever.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b A P-value ≤ 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

c P-values are obtained from the chi-squared test for categorical, and the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables (i.e., LOF and LOS).

4.3. The Impact of Comorbidities

In this study, post-treatment outcomes were compared between patients with and without comorbidity among the study groups. Notably, the prevalence of comorbidity was not significantly different between groups (P = 0.187) (Figure 2). The study results demonstrated that patients with comorbidity had longer LOF during admission, 14.5 ± 2.40 vs. 8 ± 0.80, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.058). Additionally, remission after initial treatment, LOS, and readmission rates were not significantly different between patients with and without comorbidity.

5. Discussion

Empyema is one of the most important complications of pneumonia that may cause morbidity and mortality in patients. Treatment includes antibiotic therapy in addition to different drainage techniques. Delayed or improper treatment of PPE can lead to the development of empyema (8). Pediatric empyema management is usually based on the physician’s experience and the availability of various surgical techniques in different settings. There are limited studies regarding pediatric empyema management, and no specific approach for treatment exists. In accordance with previous studies, empyema was more prevalent among children under five years in this study (11-14). This finding might be because younger children are more susceptible to streptococcal and staphylococcal infections (15). Regarding symptoms, similar to other studies, fever and cough were the most common symptoms found in this study (13-16). Some studies reported dyspnea in more than 50% of patients (12, 15, 16). However, in our study, only 21.6% of patients had a history of dyspnea, probably because younger children cannot properly describe dyspnea. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms were also common in our study, but they can be a rare symptom among empyema patients, as another study reported GI symptoms in only 7 of 61 patients (11.5%) (15). Therefore, it should be considered that the presence of GI symptoms without obvious respiratory symptoms may cause inaccurate diagnosis and delay in diagnosis and treatment of empyema.

Among 91 patients who underwent pleural fluid culture, most had negative cultures, and 15 (16.5%) patients had a positive culture. This number was identical to the 14.97% reported in another study (17). However, lower positive culture rates could also be anticipated (18). The culture result is influenced by the stage of PPE, and in the early stages, pleural fluid culture is negative. Therefore, the timing of fluid recruitment might affect the culture results. In contrast, other studies have isolated microorganisms in about 40% of patients (11, 13). In our study, antibiotic administration before admission might also have affected the results. In this regard, using the PCR technique increases the likelihood of organism isolation because it is not influenced by previous antibiotic administration. Supporting this justification, a study in Ahvaz, Iran, isolated organisms in 28.57% with pleural fluid culture and 77.14% with PCR (19). Streptococcus pneumoniae and Acinetobacter species were the most commonly isolated organisms in our patients and in other previous studies (19-23). On the other hand, some studies reported S. aureus as the most common isolated organism (13, 14, 24).

Based on our results, surgical interventions provide higher remission rates for children with empyema. However, no significant differences were observed among treatment groups in terms of mortality, complications, LOS, LOF, and readmission rates. The elevated remission rates linked with surgical techniques can be attributed to the precision of these interventions, which allow for the direct removal or treatment of the affected area, resulting in more definitive outcomes. Additionally, the selection of patients for surgical interventions may have impacted these higher remission rates, as these patients might be in better overall health or have conditions that are more amenable to surgical treatment. On the other hand, the lack of significant differences in mortality, complications, and readmission rates among the treatment groups could be due to advancements in medical care and standardized protocols, which help manage potential complications and improve patient outcomes. Furthermore, several confounding factors such as the baseline health status of patients, including age, comorbidities, and overall physical condition, may have played a role in these outcomes, leading to similar rates across different treatment groups.

Overuse or misuse of various surgical techniques in managing this issue could lead to an increase in complications and unnecessary diagnostic modalities by primary care providers. A way to properly manage children with such diseases is to use guidelines. Guidelines can help physicians with proper management. Remission was higher in the fibrinolytic group compared with the chest tube alone group. Plus, LOS and LOF were also higher in the fibrinolytic group, but it was not statistically significant. The efficacy of fibrinolytic agents has been controversial in previous studies. For example, in a prospective study by Baram and Yaldo, 98.9% of patients improved with fibrinolytic administration, and it has been recommended to treat patients with fibrinolytic administration through a chest tube before any surgery (25). However, a systematic review and meta-analysis have reported VATS to be superior to fibrinolytic administration in advanced empyema because patients who underwent VATS had lower LOS and failure rates (26). In another study, no significant difference was observed between VATS and fibrinolytic administration (27), and some other studies reported no difference in remission rate between fibrinolytic and placebo administration (28). Generally, it is believed that the use of fibrinolytic agents can facilitate drainage of effusion, especially when there is pus or thick fluid in the pleural space (7). These discrepancies may be attributed to variations in study populations, differences in treatment protocols (including fibrinolytic agents, dosages, and administration methods), and heterogeneity in disease severity across cohorts. Additionally, retrospective study designs and differences in follow-up durations may influence reported outcomes.

It is also worth noting that some factors might interfere with the antibiotic therapy outcomes reported in this study. In some previous studies, 52% of patients with empyema improved with antibiotic therapy. ICU admission and greater effusion size were associated with the need for a drainage procedure (29, 30); however, in our study, 14.4% of patients received only antibiotics, and 64.3% of them improved. This is probably because of more severe disease and a greater stage of empyema in our patients. In a study by Hassanzad et al., patients who were treated medically without any surgical interventions had lower hospital stays, but their outcomes were similar to the surgically treated patients (31). Supporting our findings, Goldin et al. found that patients undergoing chest tube placement more commonly required additional procedures, while patients undergoing initial VATS and thoracotomy had a higher remission rate (29). Additionally, a retrospective cohort study showed a lower failure rate in the VATS group and a higher need for additional drainage procedures in the chest tube group, but LOS was not significantly different between the different drainage procedures (32). Furthermore, a study by Sehitogullari et al. reported 47% remission after chest tube placement and 100% after initial surgery (33). Generally, surgery should not be done for all empyema patients, but in more advanced stages of empyema and severe loculation, decisions about the need for surgery should be made without delay. The antibiotic group had the lowest complications, probably because they received less invasive treatment or had less severe disease. Therefore, patients in the early stages of PPE can improve with early initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy without any complications. Despite their effectiveness and being less invasive, regarding the administration of the proper antibiotic, clinicians would do better to avoid its misuse.

Regarding the possible effect of comorbidities, while acknowledging no significant difference in the prevalence of comorbidity between groups, the remission rate after initial treatment was not influenced by comorbid conditions. Indeed, the remission rate, LOS, and readmission rate were not significantly different between patients with and without comorbidity. The LOF in patients with comorbidity was more than in patients without comorbidity. However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.058), but it probably indicates that fever resolves later in patients with comorbidity, while their outcome is similar to patients without comorbidity.

This study had data limitations because data were collected retrospectively. Therefore, selection bias may have occurred, as only individuals with available records were included. This could lead to an overrepresentation or underrepresentation of certain patient characteristics, potentially influencing the observed treatment outcomes. Data regarding the follow-up of the patients and long-term outcomes were also not available. The absence of long-term follow-up data restricts our ability to assess the durability of treatment effects, limiting generalizability to broader patient populations. Without long-term outcomes, it remains uncertain whether the reported results fully reflect the long-term efficacy and safety of the interventions studied. Another limitation was that our center is a tertiary referral hospital, and most of the participants were referred with more severe diseases that had also received multiple courses of antibiotics. Therefore, the results should be generalized with caution. Despite these limitations, the findings still provide valuable insights into short-term treatment responses within the study cohort. Future prospective studies with comprehensive follow-up data would help address these concerns and enhance generalizability.

More studies with a greater number of cases and randomized clinical trials are required to determine a specific approach to empyema thoracic in the pediatric group. In conclusion, the treatment choice for pediatric empyema thoracic significantly determines the remission rate. Accordingly, this study would assist in designing and implementing standardized treatment approaches for empyema among pediatric patients based on the patient’s conditions. Moreover, future longitudinal and comparative studies with more detailed patient stratification are required for more precise empyema management.