1. Background

Neonatal sepsis refers to a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) that is secondary to a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection. The overall incidence of neonatal sepsis has been reported to vary between 1 to 5 cases per 1000 live births (1-3). In some studies, the global incidence of neonatal sepsis is estimated to be even up to 22 neonates per 1000 live births, with an estimated mortality between 11% and 19%. Extrapolating these figures on a global scale, the incidence of neonatal sepsis can be estimated at approximately 3 million neonates worldwide (4). Despite ongoing advances in maternal and neonatal care, the accurate diagnosis of neonatal sepsis remains challenging. These current challenges include antibiotic resistance, culture-negative (suspected or probable) sepsis, as well as the variable and non-specific symptoms of neonatal sepsis (such as temperature instability, pallor, jaundice, lethargy, irritability, hypertonia or hypotonia, tachycardia or bradycardia, hypotension, apnea, grunting, retractions, oxygen desaturation, cyanosis, abdominal distension, feeding intolerance, diarrhea, and oliguria) (2, 5-7).

Depending on the age of presentation after birth, neonatal sepsis is divided into two groups: Early-onset sepsis (occurring within the first 7 days of life) and late-onset sepsis (occurring after 7 days of life). However, some experts limit these definitions to infections occurring within the first 72 hours of life [as early-onset neonatal sepsis (EONS)] and after 72 hours to 7 days of life (as late-onset neonatal sepsis) (3). This classification helps in the timely identification of the microbial pathogen and appropriate antibiotic selection. In spite of the fact that isolation of bacteria from sterile body fluids is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of proven sepsis, non-culture dependent diagnostic methods can also be extremely beneficial. Considering that neonatal sepsis cannot always be excluded by negative culture results and it should take 24 - 48 hours of critical time for optimal culture results preparation, various supplemental diagnostic tests based on assessment of the immune system response have been evaluated so far. It appears that lab tests such as complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, and cytokines [like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins] can play an important role in the early diagnosis of sepsis (8).

2. Objectives

In this study, we investigated the diagnostic values of CBC parameters and CRP as biomarkers of neonatal sepsis.

3. Methods

In this diagnostic test accuracy study, we investigated the diagnostic values of CBC parameters and CRP for neonatal sepsis in all newborns admitted to 17 Shahrivar hospital in Rasht, Iran, from April 2020 to September 2022. All relevant information was collected retrospectively from the accessible database of the hospital. The investigators complied with ethical principles stated by the Research Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences in all stages of the study (approval ID: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.192).

The ISI Web of Sciences, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar databases were reviewed for relevant articles published from 2010 to 2024. The keywords used included neonatal sepsis, red cell distribution width (RDW), CRP, diagnostic value, and laboratory biomarkers.

Due to the non-specific clinical features suggestive of neonatal sepsis, the inclusion criteria were breast milk feeding intolerance, decreased neonatal intake, abnormal reflex responses, fever, respiratory distress, apnea, bilious vomiting, and localized infections.

In order to minimize diverse disruptive effects on the fetal hemopoietic system, we excluded from the study those neonates who had major congenital abdominal wall defects (gastroschisis or omphalocele), anencephaly, a multiple pregnancy, congenital heart disease, asphyxia, hydrops fetalis, TORCH infections (which refers to the congenital infections of toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and other pathogens including syphilis and hepatitis B), large for gestational age (LGA), small for gestational age (SGA), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), major congenital metabolic disorders, and previous blood product transfusions. Among the possible outcomes of sepsis assessment that were excluded from the study were indeterminate results due to past medication history of recent antibiotic administration and cultures being positive for non-pathogenic bacteria.

Our final sample size of 277 neonates was divided into three main groups: Proven sepsis, probable sepsis, and non-septic neonates group. It should be mentioned that in similar studies, instead of these terms, matching words such as definite sepsis, suspected sepsis, and control group have been used. In the proven sepsis group, a positive result of culture from blood, urine, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), or other sterile body fluids in the presence of clinical signs and symptoms of infection (such as temperature instability below 36˚C or above 37.9˚C, heart rate ≥ 180 beats/min or ≤ 100 beats/min, respiratory rate > 60 breaths/min, grunting or desaturations, lethargy, or feed intolerance) was required. In the probable sepsis group, there were neonates with negative body fluid cultures and at least two positive laboratory evidence of active infection [including abnormal CRP, platelet, total leukocyte, or absolute neutrophil count (ANC); Table 1], who presented clinical signs and symptoms of infection (9-11). Whether each patient's laboratory values were within the normal ranges was determined using the age-specific reference values for CBC in neonates written in the “Lanzkowsky's Manual of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology” textbook (12). Last in order, if there was less physical, laboratory, or radiological evidence in favor of any infection, the neonate was classified in the third group.

| CBC Parameters | Age-Specific Reference Values | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-term (27 - 31 wk) | Pre-term (32 - 36 wk) | Term Infants | Birth | 12 h | 24 h | 1 wk | 2 wk | 1 mo | |

| Platelet | 215000 - 335000 | 220000 - 360000 | 242000 - 378000 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total leukocyte | - | - | - | 9000 - 30000 | 13000 - 38000 | 9400 - 34000 | 5000 - 21000 | 5000 - 20000 | 5000 - 19500 |

| ANC | - | - | - | 6000 - 26000 | 6000 - 28000 | 5000 - 21000 | 1500 - 10000 | 1000 - 9500 | 1000 - 9000 |

Abbreviations: CBC, complete blood count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count.

The CBC parameters evaluated in this study include white blood cell (WBC) count, platelet count, ANC, and RDW. The RDW is a hematological index that reflects the heterogeneity in the size of circulating erythrocytes (anisocytosis). This parameter is often considered by clinicians as a differential diagnostic biomarker of iron deficiency anemia and thalassemia (13). The RDW reference interval at birth is reported to be slightly higher than the normal reference range for older children and adults. This reference range does not change physiologically over the first two weeks of life (14). In neonatal sepsis, the acute systemic inflammatory response alters erythropoiesis and erythrocyte maturation, which results in RDW elevation. This increase in RDW level due to macrocytic reticulocytosis may indicate the severity of the underlying inflammatory response and the risk of mortality (15).

This study has also examined demographic characteristics of 277 subjects (including gender and age of neonates, age of mothers, gestational age, neonatal weight at admission, birth weight, Apgar score, and the mode of delivery) as possible risk factors for neonatal sepsis. After collecting the data based on the study proposal checklist, statistical analysis was performed utilizing SPSS software version 26 for Windows. Independent samples t-test was used to statistically compare the RDW difference between two groups of newborns with and without sepsis. In this regard, for non-parametric data, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Interaction effects of continuous independent variables (covariates) were controlled by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were performed to determine the optimal threshold indices of RDW and other CBC parameters for identifying neonates with sepsis. These diagnostic indices include sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for each biomarker’s cut-off value. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the association of RDW and other biomarkers with neonatal sepsis. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the area under the curve (AUC) and odds ratios (OR) were also calculated and used in this analysis. The kappa coefficient was used to measure the statistical level of agreement between CRP and RDW in estimated cut-off points for diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. The chi-square test was used to determine if there was any correlation among non-numeric variables. The P-value threshold for defining statistical significance in this study was considered P ≤ 0.05. However, the exact P-values higher than 0.001 were declared so that the results of this study would not be abused, unintentionally or scientifically.

Based on the results of Deka (16) and Akbarian-Rad et al. (17) studies reporting the national prevalence of neonatal sepsis as 15.98% (estimated as 16%), pre-determined sensitivity of RDW as 86% with a margin of relative error of 25% and taking into account the confidence level of 95% (Z-score = 1.96), a sample size of n ≥ 63 was calculated as follows:

nSe, sample size for adequate sensitivity; α = 0.05;

However, for more comprehensive and reliable results of the study, convenience sampling technique was used as a non-probability sampling method. Finally, we were able to collect a total of 277 samples from hospitalized patients during the determined time period. Ultimately, this method ensured that the calculated minimum required sample size was achieved for this study.

4. Results

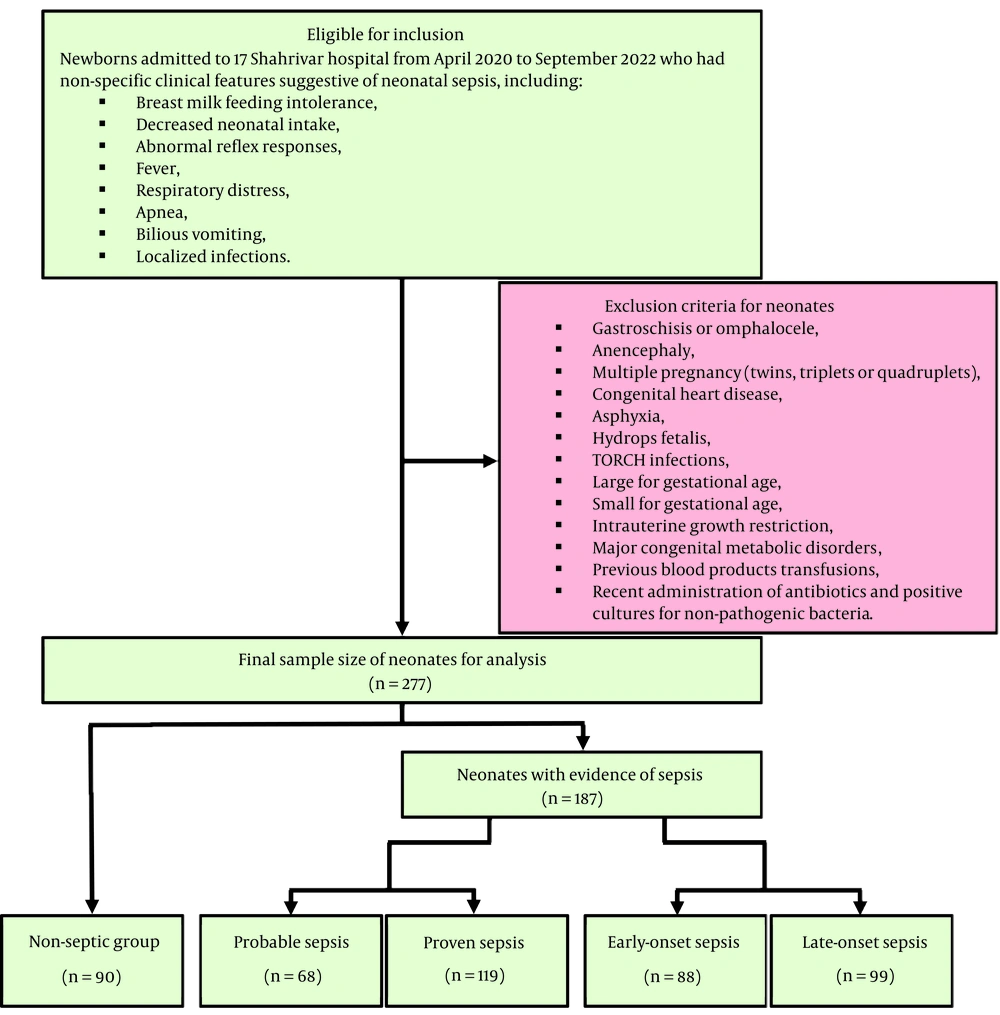

During the study period, a total of 277 neonates were analyzed retrospectively. Among these 277 subjects, there were 90 non-septic neonates (32.5%) and 187 patients with evidence of sepsis (67.5%), including 68 neonates (24.5%) with probable sepsis and 119 neonates (43%) with proven sepsis. On the other hand, among these 187 patients with evidence of sepsis, 88 neonates (31.8%) had early-onset sepsis (occurring within the first 7 days of life) and 99 neonates (35.7%) had late-onset sepsis (occurring on the 8th to 28th days of life, Figure 1). No deaths were reported in the study population.

Demographic characteristics of the neonates are shown in Table 2. In this study involving 277 participants, 179 (64.6%) were male and 98 (35.4%) were female, with no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of sepsis between the groups (P = 0.529). The incidence of sepsis (probable and proven) was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in neonates 7 days old or older (72.6%) compared to neonates younger than 7 days (50.8%). The relationship between the age of neonates (in days) and the incidence of neonatal sepsis was also significant (P < 0.001). Moreover, a significant intergroup difference (P = 0.037) was detected regarding the age of mothers (quantified in years). The average maternal age in neonates with evidence of sepsis (probable: 27.26 ± 5.95 and proven: 29.38 ± 6.16) was lower than the mothers of non-septic neonates (30.17 ± 4.97). This is despite the fact that the frequency distribution of neonatal sepsis in the determined age groups of the mothers (age less than 25 years, 25 - 30 years, 30 - 35 years, and 35 years and above) was not statistically significant (P = 0.155).

| Parameters | Non-septic Group | Probable Sepsis | Proven Sepsis | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.529 | ||||

| Male | 54 (30.2) | 46 (25.7) | 79 (44.1) | 179 | |

| Female | 36 (36.7) | 22 (22.5) | 40 (40.8) | 98 | |

| Neonatal age (d) | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 7 | 32 (49.2) | 19 (29.2) | 14 (21.6) | 65 | |

| ≥ 7 | 58 (27.4) | 49 (23.1) | 105 (49.5) | 212 | |

| Mean quantitative age | 9.46 ± 4.2 | 13.26 ± 8.26 | 15.6 ± 7.25 | 13.15 ± 7.18 | < 0.001 |

| Maternal age (y) | 0.155 | ||||

| < 25 | 10 (17.6) | 19 (33.3) | 28 (49.1) | 57 | |

| 25 - 30 | 37 (38.1) | 23 (23.8) | 37 (38.1) | 97 | |

| 30 - 35 | 25 (37.3) | 15 (22.4) | 27 (40.3) | 67 | |

| ≥ 35 | 18 (32.1) | 11 (19.6) | 27 (48.3) | 56 | |

| Mean quantitative age | 30.17 ± 4.97 | 27.26 ± 5.95 | 29.38 ± 6.16 | 29.21 ± 5.82 | 0.037 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 0.008 | ||||

| < 37 | 27 (23.7) | 37 (32.4) | 50 (43.9) | 114 | |

| ≥ 37 | 63 (38.7) | 31 (19.0) | 69 (42.3) | 163 | |

| Weight at admission (g) | 0.377 | ||||

| < 2500 | 7 (28.0) | 9 (36.0) | 9 (36.0) | 25 | |

| ≥ 2500 | 83 (32.9) | 59 (23.4) | 110 (43.7) | 252 | |

| Birth weight (g) | 0.552 | ||||

| < 1500 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 3 | |

| 1500 - 2500 | 4 (23.5) | 6 (35.3) | 7 (41.2) | 17 | |

| ≥ 2500 | 86 (33.5) | 60 (23.3) | 111 (43.2) | 257 | |

| Mean quantitative weight | 3142.63 ± 378.64 | 3152.63 ± 571.90 | 3200.46 ± 543.95 | 3171.70 ± 501.63 | 0.323 |

| Apgar score | 0.099 | ||||

| ≥ 7 | 1 (11.1) | 5 (55.6) | 3 (33.3) | 9 | |

| < 7 | 89 (33.2) | 63 (23.5) | 116 (43.3) | 268 | |

| Mode of delivery | 0.471 | ||||

| NVD | 30 (30.9) | 28 (28.9) | 39 (40.2) | 97 | |

| C-section | 60 (33.3) | 40 (22.2) | 80 (44.5) | 180 |

Abbreviations: g, grams; NVD, normal vaginal delivery; C-section, cesarean Section.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

In this study, the prevalence of sepsis in preterm neonates (probable: 32.5% and proven: 43.9%) was higher (P = 0.008) compared to neonates born at 37th week of gestation or later (probable: 19% and proven: 42.3%). No significant intergroup difference was detected regarding neonatal weight at admission, birth weight, Apgar score, and the mode of delivery.

Laboratory characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 3. Among 165 performed blood cultures, only 17 cultures; among 185 urine cultures performed, 100 cultures; and among 80 CSF cultures, only 9 cultures were positive. As defined earlier, all of these neonates were placed in the proven sepsis group.

| Parameters | Non-septic Group | Probable Sepsis | Proven Sepsis | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood culture | < 0.001 | ||||

| + | 0 | 0 | 17 (10.3) | 17 (10.3) | |

| - | 13 (7.9) | 65 (39.4) | 70 (42.4) | 148 (89.7) | |

| Urine culture | < 0.001 | ||||

| + | 0 | 0 | 100 (54.1) | 100 (54.1) | |

| - | 8 (4.3) | 59 (31.9) | 18 (9.7) | 85 (45.9) | |

| CSF culture | 0.001 | ||||

| + | 0 | 0 | 9 (11.25) | 9 (11.25) | |

| - | 0 | 42 (52.5) | 29 (36.25) | 71 (88.75) | |

| CRP | < 0.001 | ||||

| + | 2 (0.7) | 47 (17) | 77 (27.8) | 126 (45.5) | |

| - | 88 (31.8) | 21 (7.6) | 42 (15.1) | 151 (54.5) | |

| CXR | < 0.001 | ||||

| With radiographic findings of pneumonia | 0 | 15 (8) | 0 | 15 (8.0) | |

| Without radiographic findings of pneumonia | 0 | 53 (28.4) | 119 (63.6) | 172 (92.0) | |

| WBC count (cells per microliter) | 15194.89 ± 4394.26 | 15235.74 ± 4821.95 | 13841.60 ± 4609.18 | 14623.54 ± 4627.76 | 0.05 |

| ANC (cells per microliter) | 5972.52 ± 2173.68 | 5952.01 ± 3000.76 | 5459.50 ± 2587.42 | 5747.09 ± 2575.72 | 0.273 |

| Platelet count (cells per cubic millimeter) | 363.87 ± 99.96 | 370.15 ± 110.13 | 381.87 ± 109.90 | 373.14 ± 106.74 | 0.467 |

| RDW (%) | 13.37 ± 1.19 | 16.59 ± 1.92 | 16.43 ± 1.67 | 15.48 ± 2.16 | 0.001 b, c, d, < 0.001 b, c, < 0.001 b, d, 0.549 c, d |

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CRP, C-reactive protein; CXR, chest X-ray; WBC, white blood cell; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; RDW, red cell distribution width.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Non-septic group.

c Probable sepsis.

d Proven sepsis.

Qualitative CRP tests were reported positive in 2.2% of non-septic neonates (2 out of 90), 69.1% of probable septic neonates (47 out of 68), and 64.7% of proven septic neonates (77 out of 119) (P < 0.001). Among the 187 chest radiographs analyzed, only 15 neonates exhibited signs of pneumonia. Subsequently, in further investigations, all of them were categorized within the group of neonates with probable sepsis. The lower WBC count in the proven sepsis group was borderline significant (P = 0.05). The values for platelet (P = 0.467) and ANC (P = 0.273) were determined to be statistically non-significant. The average percentage of RDW in the non-septic group (13.37 ± 1.19) was significantly lower than the probable septic (16.59 ± 1.92) and proven septic (16.43 ± 1.67) groups (P = 0.001). However, the increase in RDW percentage between the probable and proven sepsis groups did not reveal any significant differences (P = 0.549).

Table 4 compares the laboratory findings of neonates according to the type of sepsis in relation to the age of presentation after birth among the study participants. While the mean percentage of RDW in the non-septic group (13.37 ± 1.19) was notably lower (P = 0.001) than the early-onset (16.68 ± 1.92) and late-onset (16.32 ± 1.59) sepsis groups, the disparities in WBC (P = 0.278), platelet (P = 0.471), and ANC (P = 0.51) levels were not statistically significant.

| Parameters | Non-septic Group | Early-onset Sepsis | Late-onset Sepsis | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC count (cells per microliter) | 15194.89 ± 4394.26 | 14610.57 ± 5239.91 | 14115.66 ± 4224.15 | 14623.54 ± 4627.76 | 0.278 |

| ANC (cells per microliter) | 5972.52 ± 2173.68 | 6081.05 ± 3116.14 | 5245.30 ± 2317.73 | 5747.09 ± 2575.72 | 0.51 |

| Platelet count (cells per cubic millimeter) | 363.87 ± 99.96 | 371.70 ± 124.24 | 382.85 ± 95.56 | 373.14 ± 106.74 | 0.471 |

| RDW (%) | 13.37 ± 1.19 | 16.68 ± 1.92 | 16.32 ± 1.59 | 15.48 ± 2.16 | 0.001 c, d, e, < 0.001 c, d, < 0.001 c, e, 0.185 d, e |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; RDW, red cell distribution width.

a Early-onset sepsis occurs within the first 7 days of life and late-onset sepsis occurs on the 8th to 28th days of life.

b Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

c Non-septic group.

d Early-onset sepsis.

e Late-onset sepsis.

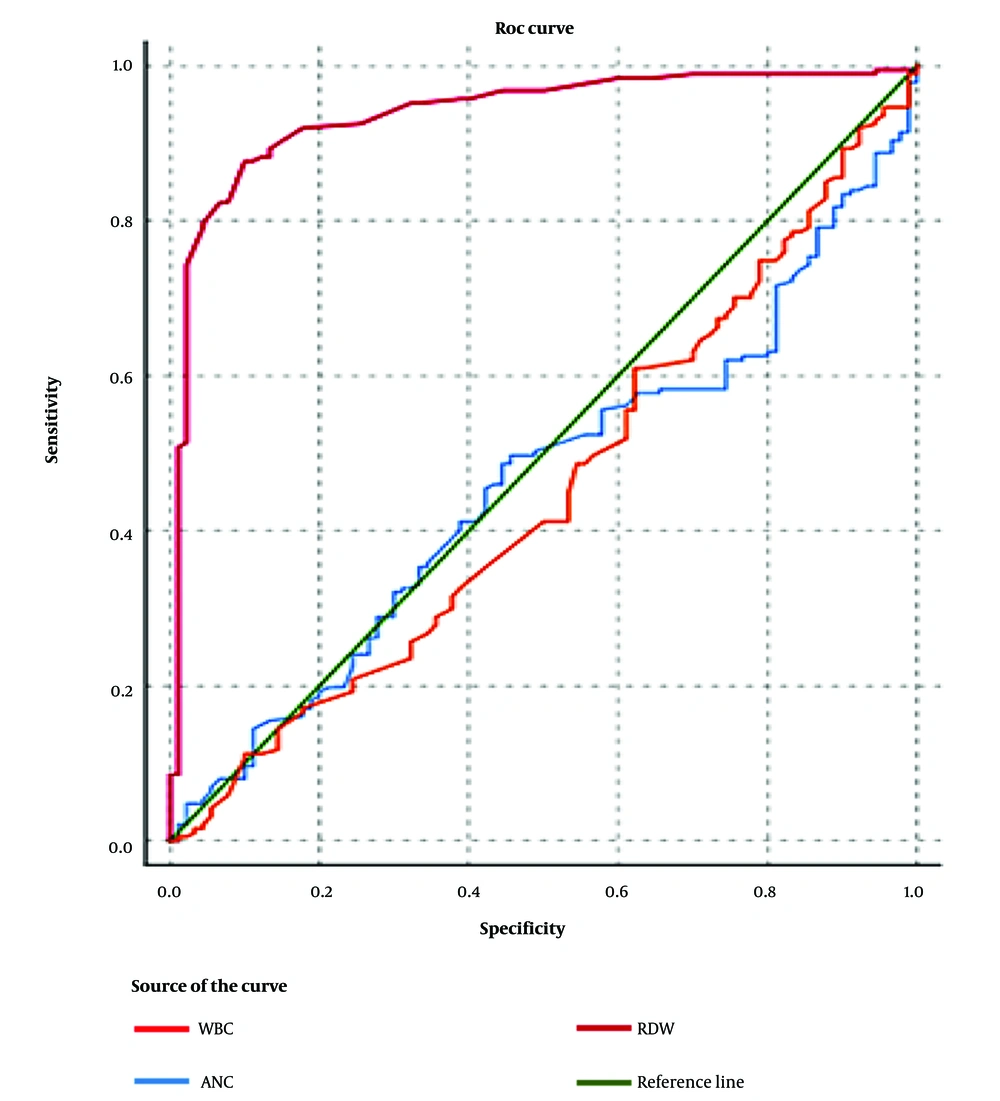

Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed a positive correlation between RDW and neonatal sepsis subsequent to covariate adjustment (adjusted OR: 5.176; 95% CI: 2.726 - 9.826; P < 0.001, Table 5). Moreover, positive correlations between age of neonates, gestational age, CRP, and WBC with neonatal sepsis were also shown in the logistic regression model. The ROC analysis was performed to determine the optimal threshold values of CBC parameters in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis (Figure 2). The AUC for RDW, WBC, and ANC was determined to be 0.938 (95% CI: 0.906 - 0.969), 0.451 (95% CI: 0.379 - 0.524), and 0.461 (95% CI: 0.391 - 0.531), respectively.

| Parameters | B | SE | P | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal age | 0.138 | 0.055 | 0.012 | 1.148 | 1.031 - 1.279 |

| Gestational age | -0.330 | 0.166 | 0.047 | 0.719 | 0.520 - 0.995 |

| WBC | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.054 | 0.9998 | 0.9996 - 1.000 |

| RDW | 1.644 | 0.327 | < 0.001 | 5.176 | 2.726 - 9.826 |

| CRP | 4.759 | 1.287 | < 0.001 | 116.671 | 9.371 - 1452.541 |

| Constant | -10.783 | 6.479 | 0.096 | < 0.001 | - |

Abbreviations: B, logistic regression coefficient; SE, standard error; P, significance probability; OR, odds ratios; CI, confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell; RDW, red cell distribution width; CRP, C-reactive protein.

In the process of identifying neonates with probable and proven sepsis in this study, an optimal RDW cut-off point of 14.1 achieves a sensitivity of 91.98% (95% CI: 87.12 - 95.44%), a specificity of 82.22% (95% CI: 72.74 - 89.48%), a positive predictive value of 91.49% (95% CI: 86.55 - 95.06%), and a negative predictive value of 83.15% (95% CI: 73.73 - 90.25%). Moreover, regarding the diagnosis of proven sepsis, the optimal RDW cut-off point of 15.5 yields a sensitivity of 70.6% and a specificity of 70%.

5. Discussion

In different studies, there are different attitudes and criteria towards neonatal sepsis. In the following, we compare related studies in tables, and point out a summary of some of these studies from different countries.

A case-control study conducted at the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of Beni-Suef University Hospital in Egypt examined the role of WBC count, hemoglobin (Hb), platelet count, CRP, and RDW in the diagnosis and prognosis of proven EONS. The study found that 20% of EONS cases exhibited leukopenia, while 80% presented with leukocytosis; conversely, 100% of control cases had a normal total leukocyte count (P < 0.001). Compatible with our study, analysis according to CRP and RDW showed significantly increased values in cases with proven EONS (43.80 ± 57.68 and 16.65 ± 4.28, respectively) compared to controls (4.20 ± 0.86 and 11.13 ± 0.62, respectively; P < 0.001 for both). Besides, the Hb level and platelet count were significantly decreased in the proven EONS group (14.36 ± 2.58 and 223.77 ± 82.15, respectively) compared to controls (17.88 ± 2.13 and 300.29 ± 67.75, respectively; P < 0.001 for both) (18).

Another related study in Egypt was conducted at the NICU at Fayoum University Hospital and Abshawai Central Hospital. Among 30 neonates with suspected neonatal sepsis and 30 controls, the level of WBC showed no statistically significant intergroup difference (P = 0.6). Consistent with our study, the mean RDW percentage was higher among cases (16.4 ± 3.8) than controls (13.7 ± 1.6; P = 0.001). Additionally, elevated CRP levels were observed in 76.7% of the cases, compared to 30% of the control group with increased levels (P = 0.01) (19).

Forty-three neonates with the established diagnosis of EONS (based on the Tollner score) and 45 healthy neonates were analyzed prospectively in a cohort study performed in Turkey. Among these hospitalized newborns in the NICU, levels of WBC (19.60 ± 6.30 103/mm3 versus 15.48 ± 5.46 103/mm3; P = 0.002), RDW (22.35 ± 5.27% versus 15.33 ± 1.87%; P < 0.001), and CRP (21.2 ± 19.06 mg/L versus 2.71 ± 0.76 mg/L; P < 0.001) were significantly higher in the EONS group compared to controls. Contrarily, there is a borderline significant correlation between WBC reduction and neonatal sepsis in our study. Meanwhile, platelet counts were significantly lower (226.09 ± 71.79 103/mm3 versus 291.56 ± 70.99 103/mm3; P < 0.001) in the EONS group. Contrary to our study, maternal age was higher in the EONS group (28.78 ± 6.25 years) in comparison with the controls (26.29 ± 5.17 years, P = 0.049). No significant intergroup differences were detected (P > 0.05) regarding neonatal age, gestational age, birth weight, red blood cell (RBC), Hb, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) values (20).

It should be noted that we simply investigated the possible impact of gestational age on neonatal sepsis as one of the demographic characteristics; because in some previous studies such as this one, no significant intergroup difference was detected regarding gestational age. However, it would certainly be better to consider this physiologically elevated RDW range in preterm infants as an assumption in future studies, and differentiate between the effect of lower gestational age and the occurrence of sepsis on RDW level.

Another cohort study in Turkey was conducted on newborns admitted to the NICU in a tertiary care university hospital by Bulut et al. The sample size was classified into 145 sepsis cases and 693 controls. There were no significant differences (P > 0.05) between the sepsis and control groups with respect to demographic characteristics (gestational age, birth weight, sex, SGA, and cesarean delivery). In the obtained laboratory data, WBC count, CRP, and red RDW values were significantly higher in the sepsis group (P = 0.027, P = 0.001, and P = 0.001, respectively); whereas the platelet count and Hb level were significantly lower (P = 0.001 and 0.043, respectively) in the sepsis group compared with the control group. The sensitivity and specificity of the optimal threshold RDW value of 17.4% were found to be 60% and 88%, respectively. The AUC of RDW value (0.799) was higher than the AUC of CRP value (0.737). Overall, results of early-onset and late-onset sepsis subgroups analysis of Bulut et al.’s study compared to our study are shown in Table 6 (10).

| Parameters | Current Study | Bulut et al. (10) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-septic Group | Early-onset Sepsis | Late-onset Sepsis | P-Value | Control Group | Early-onset Sepsis | Late-onset Sepsis | P-Value | |

| WBC count (cells per microliter) | 15194.89 (1560.0 - 25600.0) | 14610.57 (1410.0 - 25100.0) | 14115.66 (1720.0 - 21800.0) | 0.278 | 12200 (3300 - 43000) | 14200 (5600 - 47500) | 12250 (3200 - 38600) | 0.013 |

| ANC (cells per microliter) | 5972.52 (823.0 - 10800.0) | 6081.05 (209.0 - 14900.0) | 5245.30 (280.0 - 9800.0) | 0.51 | - | - | - | - |

| Hb (grams per deciliter) | - | - | - | - | 17 (8.1 - 24) | 15.2 (10.2 - 23) | 15.6 (9 - 25) | 0.001 |

| MCV (cubic microns) | - | - | - | - | 105 (87 - 134) | 107 (87 - 126) | 105 (88 - 130) | 0.205 |

| Platelet count (cells per cubic millimeter) | 363.87 (165.0 - 610.0) | 371.70 (157.0 - 781.0) | 382.85 (210.0 - 585.0) | 0.471 | 242.00 (15.0 - 704.0) | 218.00 (60.7 - 407.0) | 229.00 (15.6 - 535.0) | 0.003 |

| RDW (%) | 13.37 (11.0 - 18.7) | 16.68 (10.7 - 23.8) | 16.32 (11.9 - 19.7) | 0.001 | 15.9 (13.4 - 22.4) | 18 (14 - 24.8) | 16.9 (13.5 - 22.2) | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; Hb, hemoglobin; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; Plt, platelet (× 103); RDW, red cell distribution width.

a Values are expressed as 95% confidence interval (CI).

The comparison of changes in CBC parameters and CRP in neonatal sepsis cases compared to controls in several studies is shown in Table 7 (10, 18-24).

| Studies | Subject | CBC | CRP | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | ANC | RBC | Hb | MCV | MCH | MCHC | Plt | MPV | RDW | PDW | |||

| Current Study | Comparison of proven sepsis, probable sepsis, and control groups | ↓ a | ↓ b | - | - | - | - | - | ↑ b | - | ↑ a | - | Positive a |

| Hodeib et al. (18) | EONS group compared to control group | Leukopenia and leukocytosis a | - | ↓ a | ↓ a | - | - | - | ↓ a | - | ↑ a | - | ↑ a |

| Salim et al. (19) | Suspected neonatal sepsis group against control group | ↑ b | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ↑ a | - | ↑ a |

| Cosar et al. (20) | EONS group against control group | ↑ a | - | ↓ b | ↓ b | ↓ b | ↓ b | ↓ b | ↓ a | - | ↑ a | - | ↑ a |

| Saleh et al. (21) | Neonatal sepsis group against control group | ↑ a | - | - | ↓ b | - | - | - | ↓ a | - | ↑ a | - | ↑ a |

| Bulut et al. (10) | Neonatal sepsis group against control group | ↑ a | - | - | ↓ a | ↑ b | - | - | ↓ a | - | ↑ a | - | ↑ a |

| Karabulut and Arcagok (22) | Comparison of proven EONS, suspected EONS and control group | ↑ a | - | - | ↑ b | - | - | - | ↓ a | - | ↑ a | - | ↑ a |

| Huang et al. (23) | Neonatal sepsis group against control group | ↓ b | - | - | - | - | - | - | ↓ a | ↓ b | = b | - | ↑ a |

| Saeedi et al. (24) | Comparison of culture-positive sepsis, culture-negative sepsis, and control groups | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Thrombocytopenia a | - b | High a | - b | Positive a |

Abbreviations: ↓, decreasing trend; =, steady trend; ↑, increasing trend; WBC, white blood cell; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; RBC, red blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; Plt, platelet; MPV, mean platelet volume; RDW, red cell distribution width; PDW, platelet distribution width; CRP, C-reactive protein; EONS, early-onset neonatal sepsis.

a P-value ≤ 0.05.

b P-value > 0.05.

As indicated in Table 7, increased RDW and CRP levels are the predominant significant findings between our study and other reviewed studies. Reduction of platelet count is another common significant finding among other studies, which was contrary to the findings of ours. Additionally, we found considerable heterogeneity between studies in WBC and Hb alterations.

In another prospective analytical study in India, a total of 50 normal newborns and 50 neonatal sepsis cases were examined in terms of RDW. Consistent with our study, the mean RDW level was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in neonatal sepsis cases (18.40 ± 1.18%) than in the normal newborns (16.18 ± 1.23%). The AUC for the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis by RDW and CRP were found to be 0.938 and 0.643, respectively. An RDW cut-off of 16.95% has a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 80% in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis (16).

In a cross-sectional study, 111 full-term newborns aged 1 - 28 days with blood culture proven neonatal sepsis admitted to the NIC) at Soba University Hospital in Sudan were evaluated for WBC count, platelet count, RDW, and CRP. Out of 111 proven septic neonates, 62% had leukocytosis (WBC > 20000/mm3), 16.2% had leukopenia (WBC < 5000/mm3), 18.9% had thrombocytosis (platelets > 450000/mm3), and 52.2% exhibited thrombocytopenia (platelets < 140000/mm3). Qualitative CRP tests were reported positive in 90.1% of patients. The mean RDW was 19.3%, with 92% of participants showing elevated levels (25).

In addition to the potential use as a diagnostic index of acute infection severity, CRP level is an important factor in evaluating the treatment process. The study of Oboodi et al. showed a decreasing trend of CRP value following antibiotic treatment for neonatal sepsis (26).

Other laboratory biomarkers besides CBC parameters and CRP have also been evaluated for neonatal sepsis in various studies. Increased phosphorus and procalcitonin levels are among these serum laboratory alterations reported for neonatal sepsis (22, 27, 28). Recent studies indicate that decreased levels of serum microRNAs (such as miR-34a-5p and miR-199a-3p) may act as early biomarkers in neonatal sepsis (29).

Although the comparatively large sample size was one of our study's notable advantages, there were certain limitations as well. In this study, we assessed the RDW level in neonates with proven sepsis in comparison to those with probable sepsis or non-septic ones, and were unable to observe any alterations in RDW levels among the septic neonates as a result of administered treatments. As a retrospective study, aside from the CBC parameters and CRP, which were routinely assessed in the hospital laboratory for suspected infants of sepsis, it was not feasible to evaluate other markers of inflammation, including procalcitonin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), or TNF-α. Investigating these markers of inflammation in a laboratory setting separate from the hospital, or supplying them with specialized laboratory kits, would require a financial allocation beyond our capabilities. Because this study was retrospective, bias and poor quality of the data collection were also possible.

5.1. Conclusions

Neonatal sepsis is a critical global health issue, and numerous laboratory studies have been conducted on its potential diagnostic biomarkers. The CBC and CRP are undoubtedly among the most accessible and cost-effective options available in any laboratory setting. Consistent with previous studies, our findings showed that elevated RDW level and positive CRP can play an important role in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. We recommend utilizing RDW alongside other clinical or laboratory parameters (such as sterile body fluid cultures and CRP), as a readily available tool to facilitate timely diagnosis and improve clinical decision-making regarding neonatal sepsis. More comprehensive, analytic, and statistical studies are required in the future to establish a universally accepted diagnostic criteria such as the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and determine the accurate diagnostic RDW cut-off for neonatal sepsis.