1. Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an inflammatory and autoimmune, chronic progressive disease of the intestine involving the following three: Ulcerative colitis (UC), indeterminate colitis, and Crohn's disease (1). The disease represents uncontrollable, chronic inflammation of the mucosa of the intestines, and it may affect any portion of the digestive tract (2). Clinical manifestations of IBD are dependent on the area of the gastrointestinal tract involved (3). Chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, blood passage with stool, anorexia, failure to gain adequate weight, or actual weight loss are common among both types of cases. The exact cause of the disease is still unknown (4). The diseases are most commonly diagnosed during adolescence, as well as the early stages of adulthood, and are increasing in incidence in children. Genetic contexts cause diseases through an uncontrolled mucosal immune response to the intestinal microflora. Four percent of the cases of IBD are diagnosed before five years and 18% of cases are diagnosed before the age of ten (5). The incidence rate of IBD in the pediatric population is about 10 per 100,000 children in the United States and Canada, and it is increasing (3, 5-7).

Among these patients, the goal of treatment is the elimination of symptoms, the restoration of life quality with normal growth, and a decrease in complications. The long-term use of the drugs does not suit the maintenance treatment because many complications may result from them. Medical therapy with corticosteroids causes the clinical regression of the disease, which brings about mucosal healing (8). This is achieved by using monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a proinflammatory cytokine in Crohn's disease and UC, which has brought a revolution. First, in the anti-TNF agents, infliximab is administered to children in clinical trials, which is FDA approved for use in children for the treatment of moderately to seriously active Crohn's and UC. Infliximab also enhances growth in children who have growth failure (9).

Although several studies have established the short-term efficacy of infliximab in pediatric and adult IBD populations, there are relatively few studies assessing the impact of infliximab on disease severity using standardized pediatric activity indices over an extended period in diverse regions, particularly in Middle Eastern pediatric cohorts. Additionally, the influence of demographic factors and differences in treatment initiation (first-line vs. refractory cases) on treatment response in children remains underexplored.

Considering that IBDs among children are chronic and debilitating conditions that necessitate lifelong treatment, and the side effects of currently used drugs, a less dangerous and more effective drug is needed. Several studies have been conducted showing the usefulness of this drug in children with IBD (10-12).

The current study was conducted to compare the severity of diseases in patients with IBD treated with infliximab before and after treatment in 2015-2020. Despite the well-established efficacy of treatment with infliximab in the management of pediatric IBD, there has still been a knowledge deficit regarding the influence of this medication on the severity of disease in children over a defined period. Previous studies have primarily focused on adult populations or short-term outcomes, leaving a paucity of data on pediatric patients. This study aims to compare disease severity before and after infliximab treatment in children with IBD at a tertiary center between 2015 and 2020. By focusing on objective changes in standardized severity scores [Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) and Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI)], and analyzing the influence of demographic factors, our research seeks to address current gaps and provide real-world data to optimize clinical management protocols for pediatric IBD.

2. Objectives

This cross-sectional study addresses this gap by evaluating the changes in disease severity before and after infliximab treatment in a pediatric cohort over a five-year period. The novelty of this research lies in its focus on a diverse pediatric population, the use of standardized severity scoring systems, and the detailed analysis of demographic factors. By providing a snapshot of infliximab’s effectiveness, this study contributes valuable insights into optimizing treatment protocols and improving clinical outcomes for children with IBD.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This was a retrospective cross-sectional study conducted on children with IBD who received infliximab treatment from 2015 to 2020 at Mofid Children's Hospital, which is a tertiary center for pediatrics.

3.2. Study Population and Sample Size

This is a retrospective study conducted as a census of all eligible pediatric IBD patients treated with infliximab at our center between 2015 and 2020. Accordingly, all patients who met the inclusion criteria during this period were included in the analysis.

A total of 31 patients were initially considered for the study. However, two patients had incomplete records, and one patient could not complete the treatment course due to complications, so they were excluded from the study. Consequently, 28 patients were included in the final analysis.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This study involved children who had active IBD — either Crohn's disease, UC, or indeterminate colitis — treated by infliximab from the year 2015 to 2020, and whose medical records were complete. Patients with incomplete medical records and those unable to complete the treatment course of infliximab owing to certain complications were excluded.

3.4. Data Collection

Patient data, including gender, age at the time of infliximab initiation, duration from diagnosis to the start of infliximab treatment, and disease type, were recorded. Patients were classified into three groups based on their disease type: Crohn’s disease, UC, and indeterminate colitis. Age was recorded in years, and disease severity was assessed using the PUCAI and the PCDAI.

3.5. Disease Severity Scoring

For Crohn’s disease:

- A score of 30 or higher was interpreted as moderate to severe.

- A score below 10 indicated inactive disease.

For UC:

- A score above 65 was considered severe.

- A score of 30 - 64 was considered moderate.

- A score of 10 - 29 was considered mild.

- A score below 10 indicated inactive disease.

A reduction of 12.5 points after initiating treatment was considered a suitable response to infliximab.

3.6. Treatment Protocol

Infliximab was administered in at least four doses: At baseline (week 0), week 2, and week 6 as induction therapy, followed by maintenance therapy every eight weeks. All injections were administered uniformly across the three disease groups. Disease severity (PUCAI, PCDAI) was evaluated and recorded at each of these time points. All patients received infliximab at a dosage of 8 - 10 mg/kg. Pre-treatment screening for latent tuberculosis infection (e.g., PPD or IGRA) and viral hepatitis was not systematically performed for all patients during the study period due to institutional practices and retrospective data availability.

3.7. Bias and Blinding

Potential sources of bias were minimized by including only patients with complete medical records and by excluding patients who could not complete the treatment course due to complications. As this was a retrospective study based on a review of existing medical records, neither investigator nor patient blinding was applicable.

3.8. Patient Categorization

Patients were categorized into three groups based on their treatment plan:

1. The first group was the patients who presented with a flare-up of the disease symptoms. These patients were initially treated with non-biological drugs.

2. The second group of patients was treated with infliximab immediately after the disease diagnosis and according to the severity of clinical symptoms.

3. The patients who did not have a satisfactory clinical response to the mentioned initial treatments were placed in the third category.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by the SPSS software, version 26. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize patient demographics and characteristics of disease. Comparative analyses were done to assess the change in severity of the disease before and after treatment using infliximab. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3.10. Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the relevant local ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1401.126. The consent form was obtained from the parents or their guardians who participated in the study.

4. Results

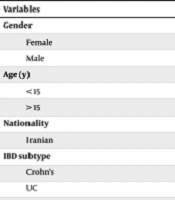

A total of 28 pediatric IBD patients were analyzed. Key demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 12.3 years, and the mean interval from diagnosis to infliximab initiation was 4.2 years. Disease severity decreased significantly following infliximab treatment, from 66.2 ± 14.7 at baseline to 6.5 ± 11.6 at week 14 (P < 0.05).

| Variables | No (%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.72 | |

| Female | 14 (50) | |

| Male | 14 (50) | |

| Age (y) | ||

| < 15 | 18 (64.3) | 0.72 |

| > 15 | 10 (35.7) | 0.37 |

| Nationality | ||

| Iranian | 28 (100) | N/A |

| IBD subtype | 0.37 | |

| Crohn's | 13 (46.4) | |

| UC | 15 (53.6) | |

| Indeterminate colitis | 0 | |

| Cause of infliximab initiation | 0.02 | |

| First line | 3 (10) | |

| Flare up | 6 (20) | |

| No Response to Other Rx | 19 (70) |

Abbreviation: IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Before the treatment, the average severity of the disease was 66.20 ± 14 based on the standard criteria for measuring IBD in children. The average disease severity was reported as 17.7 ± 15.6 after two weeks, 7.6 ± 13.2 after six weeks, and 6.5 ± 11.6 after 14 weeks. Also, according to the severity of the disease before treatment, one patient had mild disease, 13 had moderate disease, and 14 had severe disease.

Severe disease was not reported in any patient in the following weeks. In the second week, 18 patients, and in the following weeks, 23 patients reported a disease severity below 10. In acute cases, the severity of the disease was higher, but during 14 weeks of treatment with infliximab, this reduction was significantly different between the three groups of patients (P-value = 0.02).

No significant difference was seen in the disease severity based on age (P-value = 0.72); type of disease (P-value = 0.37) or sex (P-value = 0.72).

5. Discussion

IBD has affected over 2.5 million people in Europe, and its prevalence is increasing in Asia and developing countries (13). The prevalence of this disease in children has also been increasing in the last decade, which can be due to genetic factors, environmental factors, and the inflammatory response to intestinal microbiome changes (14).

In the present study, 28 patients participated, and 50% of them were females. Eighteen patients were under 15 (64.3%), and ten were over 15 (35.7%). The average age of the patients was 12.31 ± 0.7. Of these, 13 (46.4%) had Crohn's disease, and 15 (53.6%) had UC. Infliximab was begun in three patients as the first line of treatment, six patients following a disease flare, and 19 patients due to a lack of response to other treatments. The average time from the diagnosis of the disease to the start of the drug was 4.2 years. Before the treatment, the average disease severity in the patients was 66.20 ± 14.7 based on the standard criteria for measuring IBD in children. The average disease severity was reported as 17.7 in two weeks, 7.6 in six weeks after treatment, and 6.5 after 14 weeks. Furthermore, according to the disease severity before treatment, one patient had mild disease, 13 had moderate disease, and 14 had severe disease. In acute cases, the disease severity was higher, but during 14 weeks of treatment with infliximab, this reduction was significantly different between the three groups of patients. No significant difference was found in severity based on age, type of disease, and gender.

In a study by Ananthakrishnan et al., the effectiveness of infliximab and adalimumab in patients with Crohn's disease and UC was determined, and they finally concluded that the effectiveness of the drugs is similar in both disease groups (UC and Crohn's), consistent with our study's findings. This consistency with our results reinforces the efficacy of infliximab in treating moderate to severe UC (15).

In a systematic review and meta-analysis by Salaman et al. of real-world studies comparing infliximab and adalimumab as first-line anti-TNF treatments in moderate to severe patients with UC, data were drawn from multiple major databases. The findings showed that infliximab achieved significantly higher induction response rates than adalimumab, while no significant difference was found between the two drugs in the maintenance phase. Regarding safety, infliximab was linked to a higher rate of overall adverse events, whereas serious adverse events occurred slightly more often, though not significantly, in the adalimumab group. The study concluded that infliximab may be preferred for its superior induction efficacy, but the choice between infliximab and adalimumab should be individualized based on the patient’s clinical profile (16).

In our study, age did not influence treatment response, which contrasts with deBruyn et al.'s findings, suggesting the need for further investigation into age-related factors. Since a young age and low body weight affect infliximab concentration (17), prospective studies should be performed in a preventive setting in pediatric patients with UC. Clinicians caring for children with UC should carefully adjust and monitor infliximab to optimize the response (17).

5.1. Limitations and Suggestions

This study has several important limitations. First, the relatively small sample size (28 patients) limits the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. As a single-center study, our cohort may not fully represent the broader pediatric IBD population. Second, the retrospective design inherently introduces certain biases, such as reliance on the accuracy and completeness of existing medical records, which may result in missing or incomplete data. Specifically, pretreatment screening for latent tuberculosis (e.g., PPD or IGRA) was not systematically documented for all patients. Furthermore, monitoring for adverse drug reactions, including hepatotoxicity via liver function tests, was performed according to variable routine clinical practice rather than at standardized intervals for research purposes. This lack of systematic safety data collection prevents a formal assessment of the treatment’s safety profile in our cohort. Third, there is the possibility of selection bias in patient recruitment, since only children who initiated and completed infliximab treatment during the study period with full documentation were included, possibly excluding patients with different disease courses or outcomes. These factors should be considered when interpreting our results. Future multicenter, prospective studies with larger cohorts are needed to confirm our findings and further clarify infliximab’s long-term effectiveness and safety in pediatric IBD.

5.2. Conclusions

In summary, infliximab significantly reduced disease severity in children with IBD in this real-world setting. These results support considering infliximab as an effective option for pediatric patients, especially those with moderate to severe disease or poor response to conventional therapy. Early initiation and careful monitoring of infliximab may improve disease control and quality of life in this population. However, the study’s retrospective design and small sample size may limit the generalizability of these findings and introduce potential selection bias. Larger, prospective studies in diverse populations are recommended to confirm these results and further guide optimal use of infliximab in pediatric IBD.