1. Background

The COVID-19 pandemic began with the emergence of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in late 2019. This highly contagious virus spread rapidly worldwide, significantly affecting public health, economies, and healthcare systems (1, 2). The SARS-CoV-2 spreads through respiratory droplets and aerosols, with symptoms ranging from asymptomatic to severe respiratory failure and death (3). COVID-19 mortality rates were higher among patients aged ≥ 65 years, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native populations, males, and patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Non-communicable diseases, including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular conditions, and cancer, have been identified as risk factors for mortality (4). Most COVID-19-related deaths occur in hospitals, with an inpatient fatality rate of 59% in 2022 (5). Children are less affected by COVID-19 than adults (4). COVID-19 is milder in children and presents mainly as a self-limiting, upper respiratory tract infection. While mortality rates among pediatric cancer patients with COVID-19 match those of the general pediatric population, evidence suggests a higher risk of death among children with malignancies. Studies show COVID-19 incidence in children with cancer exceeds that in the general pediatric population, with a virus-related mortality of approximately 4% in large international cohorts (6, 7). Other reports indicate that children with cancer face an increased risk of severe disease due to their immunocompromised status and underlying conditions. These studies show that 20% of children with cancer who contract SARS-CoV-2 develop severe infections, compared to 1 - 6% of children without cancer (8, 9). Despite the risks for pediatric oncology patients, most research has focused on adults, leaving knowledge gaps regarding SARS-CoV-2 in children with cancer, particularly in resource-limited settings such as Iran (10). Iran's healthcare system faced major challenges during the pandemic, complicating care for high-risk groups (11, 12). This study aimed to address the knowledge gap regarding COVID-19 in pediatric oncology patients by investigating the clinical outcomes, complications, and risk factors associated with the disease. These findings are intended to enhance our understanding of how COVID-19 affects immunocompromised children and to inform clinical practices and public health strategies for improving outcomes in similar populations.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to address knowledge gaps regarding COVID-19 in pediatric oncology patients by investigating clinical outcomes, complications, and risk factors. These findings will enhance the understanding of COVID-19 in immunocompromised children and inform clinical practices to improve outcomes in similar populations.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This retrospective cohort analysis investigated the impact of COVID-19 on pediatric patients with malignancies. The study was conducted at the Amir Oncology Teaching Hospital, the pediatric oncology referral center of southern Iran, and encompassed the period from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 to the end of September 2022.

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

1. The study included all pediatric patients under the age of 18 years who were tested for COVID-19 based on clinical suspicion by SARS-CoV-2 real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay, as recorded in the official database of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (http://coronalab.sums.ac.ir/).

2. Patients diagnosed with a hematologic malignancy (e.g., leukemia or lymphoma) or solid tumor (e.g., neuroblastoma or brain tumor).

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded if (1) COVID-19 diagnosis was not confirmed by RT-PCR assay and was instead based solely on clinical or imaging findings [e.g., chest computed tomography (CT) scan]; (2) unsatisfactory samples were not repeated, using standard sampling protocols.

3.4. Data Collection

Patient demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected from hospital records and systematically recorded using pre-designed questionnaires. The information included details on the underlying malignancy, COVID-19 symptoms, treatments administered, and clinical outcomes. Radiological findings, including chest radiography (CXR) and lung CT scans of patients with COVID-19, were reviewed by an attending radiologist at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

3.5. Radiological Severity Definitions

The severity of pulmonary involvement on chest imaging was classified as mild, moderate, or severe according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.

1. Mild: Minimal or focal ground-glass opacities or consolidations involving a small area of the lung with no signs of respiratory distress.

2. Moderate: Multifocal ground-glass opacities or consolidations involving more than one lobe but without extensive lung involvement or features of severe disease.

3. Severe: Diffuse, bilateral lung involvement with extensive ground-glass opacities, consolidations, or features suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), often accompanied by clinical signs of severe respiratory compromise.

These definitions were applied by an attending radiologist in accordance with the WHO guidelines for the use of chest imaging in COVID-19 (13).

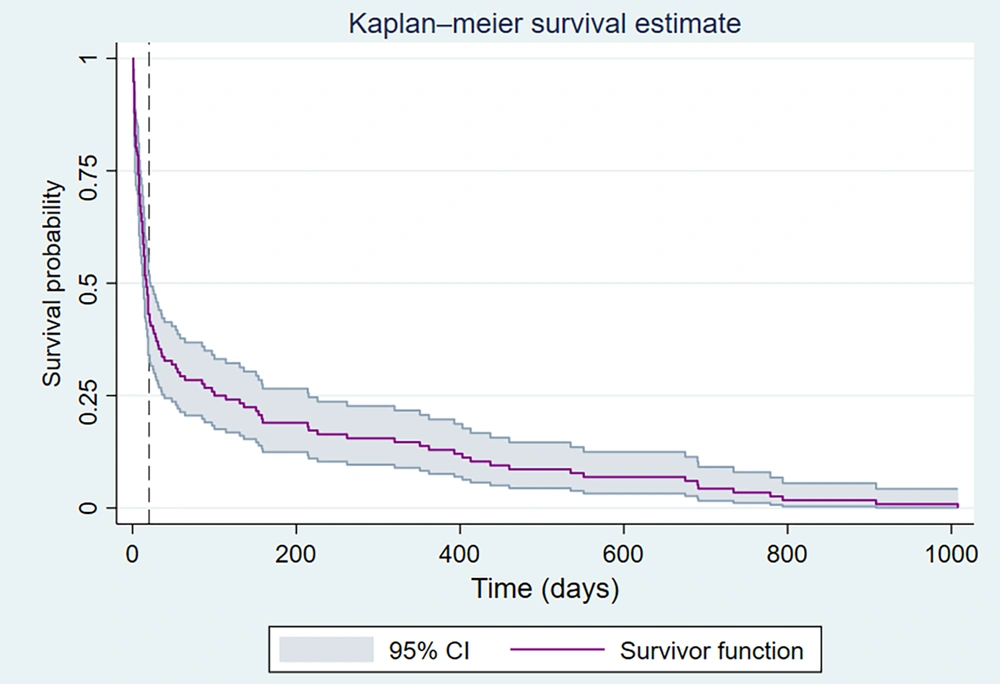

3.6. Follow-up Duration

All pediatric oncology patients included in this study were followed up from the time of COVID-19 diagnosis or hospital admission until the occurrence of the outcome of interest (death, relapse, or last known follow-up), with a maximum follow-up period of 1,000 days. Survival analyses (Figure 1) were conducted based on the follow-up duration to ensure a comprehensive outcome assessment for all participants.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates for pediatric oncology patients with COVID-19. The survival curve displays the probability of survival over time (in days) following the COVID-19 diagnosis. A total of 146 pediatric cancer patients with confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection were included in this analysis. During the follow-up period, 22 (15%) patients died of the disease. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the survival function. The median survival time of the patients was 21 days.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS® for Windows® version 21.0 (SPSS Software, CA, USA). The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. The association between parametric variables was analyzed using the t-test, whereas the chi-square test was used for the qualitative data. Risk factors were assessed using regression analysis with Stata® software (version 17; Stata Corp, Texas, USA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Survival probabilities were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods, specifically for the subgroup of pediatric oncology patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Time zero was defined as the date of COVID-19 diagnosis, and patients were followed up until death or the last known follow-up.

3.8. Ethical Considerations

All patient data were anonymized to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of the patients. The study was designed to comply with national norms and regulations for conducting medical research in Iran, as well as ethical principles. The study was approved by the "Iran National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research" with approval ID: IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1402.264.

4. Results

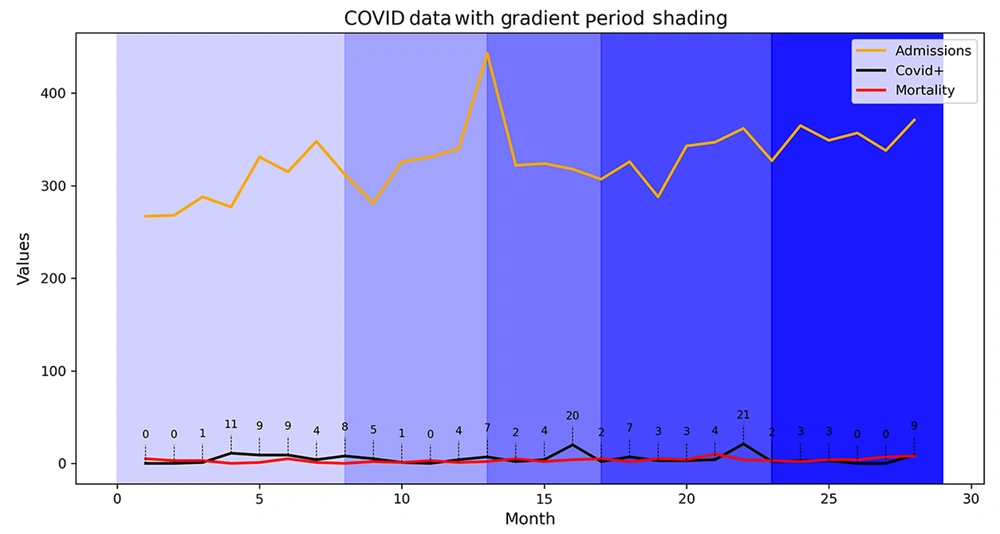

A total of 9,171 pediatric patients were admitted to the Amir Oncology Teaching Hospital during the study period, with 1,944 of them tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. Among those tested, 146 (7.5%) were positive (Figure 2). Among the COVID-19 pediatric cancer patients, 67 (46%) were girls and 78 (54%) were boys, with no significant difference in sex distribution (P = 0.74). The age distribution of the COVID-19 cohort was as follows: Two percent were under 12 months old, 39% were between 1 and 5 years old, 34% were between 6 and 12 years old, and 23% were between 13 and 18 years of age. There was no significant difference in age distribution between the SARS-CoV-2 positive and negative groups (P = 0.20).

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection rates in pediatric patients with cancer: The total number of pediatric patients hospitalized at the Amir Oncology Teaching Hospital, the positive rate for SARS-CoV-2 based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, and the overall mortality rate. The gradient shading indicates five national peaks in Iran, covering the period from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 to the end of September 2022.

The most prevalent underlying malignancy among COVID-19 patients was acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), which accounted for 41% of cases, followed by sarcoma (10%), lymphoma (9%), and brain tumors (8%). A detailed summary of the demographic and clinical characteristics is presented in Table 1.

| Parameters | SARS-CoV-2 PCR | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (N = 146) | Negative (N = 704) | ||

| Gender | 0.747 | ||

| Female | 67 (46) | 67 (45) | |

| Male | 78 (54) | 389 (55) | |

| Age | 0.235 | ||

| < 12 mo | 4 (2.76) | 34 (4.83) | |

| 1 - 5 y | 57 (39.31) | 301 (42.8) | |

| 6 - 12 y | 50 (34.48) | 251 (35.71) | |

| 13 - 18 y | 34 (23.45) | 118 (16.77) | |

| Malignancy | 0.207 | ||

| Leukemia | 60 (41.38) | 240 (34.1) | |

| Lymphoma | 13 (8.97) | 52 (7.39) | |

| Sarcoma | 15 (10.34) | 65 (9.25) | |

| Neuroblastoma | 12 (8.28) | 78 (11.07) | |

| Others | 15 (10.34) | 55 (7.82) | |

Abbreviations: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

The clinical presentation of COVID-19 is primarily characterized by fever, which occurs in 48% of the patients. This was followed by cough (15%), generalized weakness (7.53%), and rhinorrhea (2%). The detailed distribution of the symptoms is presented in Table 2.

| Sign and Symptoms | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Respiratory symptoms | |

| Cough | 22 (15.07) |

| Sore throat | 3 (2.05) |

| Rhinorrhea | 3 (2.05) |

| Dyspnea | 2 (1.37) |

| Mild pneumonia | 3 (2.05) |

| Systemic manifestations | |

| Fever > 38°C | 69 (48) |

| Generalized weakness | 11 (7.53) |

| Body pain | 1 (0.68) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | |

| Diarrhea | 2 (1.37) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (0.68) |

Radiological findings were obtained from 127 COVID-19 patients who underwent CXR. Among the CXR results analyzed, 38.6% showed no abnormalities, 30.7% were classified as mild, 19.7% as moderate, and 11% as severe (Table 3).

| Findings | Chest X-ray | CT Scan |

|---|---|---|

| No abnormalities | 49 (38.58) | 6 (42.86) |

| Mild pneumonia | 39 (30.71) | 5 (35.71) |

| Moderate pneumonia | 25 (19.69) | 2 (14.29) |

| Severe pneumonia | 14 (11.02) | 1 (7.14) |

| Total | 127 (100) | 14 (100) |

Abbreviation: CT, computed tomography.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

A subset of 14 patients underwent CT, with results indicating that 42.86% had no abnormalities, 35.71% showed mild changes, 14.29% exhibited moderate abnormalities, and 7.14% had severe findings (Table 3). Only 0.7% of the patients required admission to the ICU, and 1.54% required mechanical ventilation. Additionally, 30.82% had a history of recent travel, and 6.16% reported known exposure to individuals diagnosed with COVID-19. A total of 128 patients died during the follow-up period, with a 50% decrease in survival probability within the first three weeks.

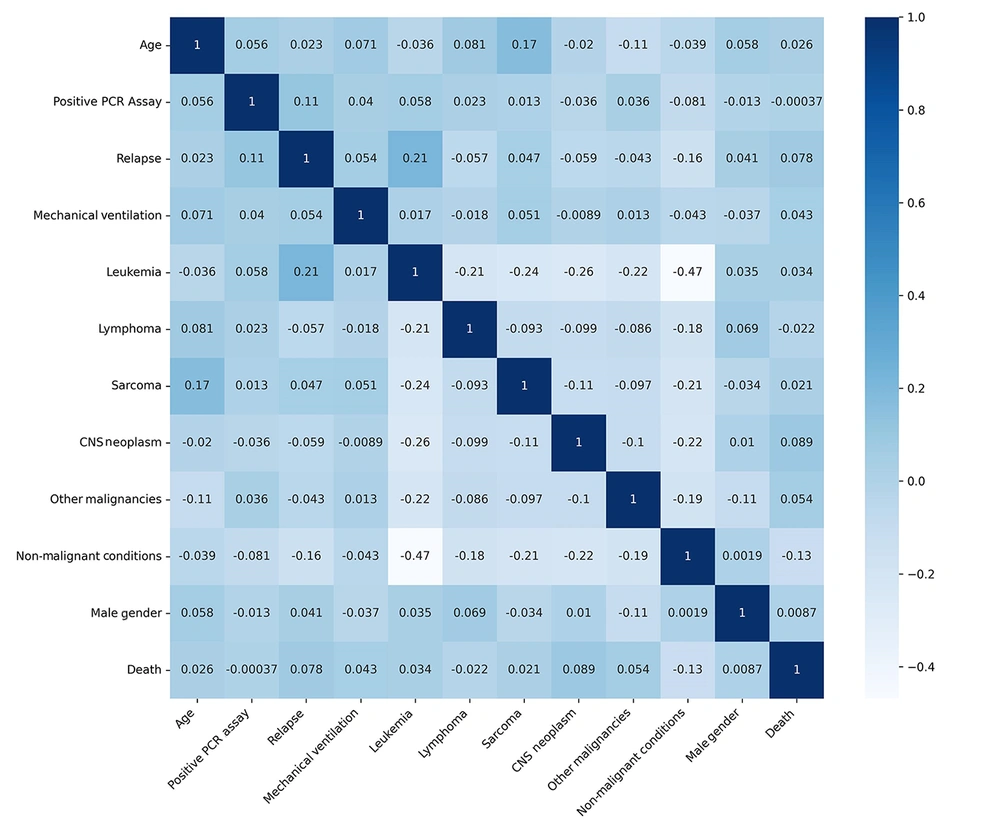

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curve for the COVID-19-positive pediatric oncology cohort (n = 146). The median survival time was 21 days, with a 50% survival probability occurring approximately 3 weeks (21 days) post-COVID-19 diagnosis. However, the Pearson correlation coefficient did not identify any significant association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and mortality. Figure 3 shows a correlation heatmap depicting the associations between mortality and multiple clinical and demographic factors in pediatric patients suspected of having COVID-19.

Fifty-five patients experienced a relapse of malignancy, with only 18 of these cases occurring in COVID-19 patients (11 relapses occurred before COVID-19 infection). Of the COVID-positive patients, seven experienced a relapse of malignancy within 16 weeks following the COVID-19 diagnosis, as determined by the Kaplan-Meier survival estimate. Among patients with COVID-19 with a history of relapse, the mean time from relapse to SARS-CoV-2 acquisition was 321.27 ± 610.12 days. In contrast, the average duration of relapse following SARS-CoV-2 infection was 245.85 ± 213.24 days.

The multivariate modeling results identified several factors associated with mortality, including male sex [adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.07; P = 0.728; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.728 - 1.575], disease relapse (aOR: 2.09; P = 0.026; 95% CI: 1.090 - 4.040), age under 12 months (aOR: 2.62; P = 0.010; 95% CI: 1.255 - 5.498), need for mechanical ventilation (aOR: 1.46; P = 0.286; 95% CI: 0.724 - 2.971), and neuroblastoma (aOR: 3.38; P = 0.005; 95% CI: 1.444 - 7.922). However, only relapse, age < 12 months, and neuroblastoma were significantly associated with increased mortality (P < 0.05). The relationship between COVID - 19 positivity and mortality was not statistically significant (aOR: 0.96; P = 0.881; 95% CI: 0.578 - 1.60; Table 4).

| Factors | aOR (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Gendre (male) | 1.07 (0.72 - 1.57) | 0.728 |

| Disease relapse | 2.09 (1.09 - 4.04) | 0.026 |

| Age (< 12 mo) | 2.62 (1.25 - 5.49) | 0.010 |

| SARS-CoV-2 positive PCR | 0.96 (0.57 - 1.60) | 0.881 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.46 (0.72 - 2.97) | 0.286 |

| Neuroblastoma | 3.38 (0.10 - 0.19) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: aOR (95% CI), adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence interval; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2.

Multivariate analysis of relapse predictors revealed that male sex (aOR: 1.38), age between 6 - 12 years (aOR: 1.52), age between 13 - 18 years (aOR: 1.23), and positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR assay (aOR: 2.34) were significant. However, only a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR assay result and leukemia were significantly associated with relapse (P < 0.05). It is crucial to highlight that cancer relapse occurred before the onset of COVID-19. This suggests that patients who experienced relapse were more likely to contract COVID-19 during their treatment (Table 5).

| Factors | OR | P-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 1.38 | 0.276 | 0.77 - 2.49 |

| Age (y) | |||

| 6 - 12 | 1.52 | 0.187 | 0.81 - 2.85 |

| 13 - 18 | 1.23 | 0.609 | 0.55 - 2.75 |

| SARS-CoV-2 positive PCR | 2.34 | < 0.001 | 1.26 - 4.34 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.88 | 0.184 | 0.73 - 4.80 |

| Diagnose (leukemia) | 5.33 | < 0.001 | 2.87 - 9.89 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the impact of COVID-19 on pediatric oncology patients, with a particular focus on survival, relapse, and disease progression. The results indicate that while COVID-19 has significant implications for pediatric oncology patients, the severity of illness, underlying malignancy, and treatment protocols play crucial roles in determining outcomes. These findings are consistent with emerging evidence of the vulnerability of immunocompromised populations to COVID-19 and highlight the need for tailored clinical approaches to manage these patients during the pandemic.

The mortality rate among COVID-19-positive patients was 15%, which is higher than that in many high-income countries (HICs). However, the higher mortality rate observed among pediatric oncology patients with COVID-19 in Iran aligns with findings from other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This is largely due to systemic healthcare limitations, such as treatment delays, limited ICU and ventilator access, and shortages of supportive care. These resource constraints complicate the management of vulnerable patients and may confound mortality data. Addressing these healthcare disparities is crucial for improving survival and reducing inequities in pediatric cancer care, especially during the pandemic (14-16).

The observed high mortality rate among pediatric oncology patients with COVID-19 was not independently attributed to COVID-19 infection after adjusting for confounding factors such as age, cancer relapse, malignancy type, and clinical severity. This aligns with other studies showing that underlying health conditions and cancer-specific factors have a greater impact on mortality risk than the viral infection itself, emphasizing the necessity of thorough risk adjustment in analyzing outcomes in complex patient groups (17-19). Additionally, our findings underscore the need to strengthen infection prevention, early detection, and care for pediatric cancer patients in Iran, thereby providing valuable data for regional policymakers and clinicians managing similar populations in the future. Our study adds to the evidence from Iran and the Middle East, helping to fill the gap in region-specific data and inform contextually relevant clinical and public health interventions in the region.

In this cohort, COVID-19 was detected in 7.5% of the hospitalized children. The demographic analysis revealed no significant differences in age and sex between COVID-19-positive and COVID-19-negative patients, aligning with the existing literature that indicates sex does not significantly influence COVID-19 susceptibility in pediatric populations (20). Most COVID-19-positive pediatric oncology patients in our study presented with mild-to-moderate symptoms, with the most common complaints being fever, general weakness, and cough. These findings mirror the general trend in pediatric COVID-19 cases, where most children experience mild illness with low rates of severe complications (21). The requirement for mechanical ventilation in 1.54% of cases and ICU admission in 0.7% of cases suggests that a small subset of pediatric oncology patients experienced severe illness. This proportion is consistent with data from large-scale studies that reported a lower incidence of critical COVID-19 among children (22, 23). In line with these findings, our study suggests that most pediatric oncology patients with COVID-19 can recover with minimal intervention.

Our analysis indicated that 15% of COVID-19 patients died, highlighting a higher mortality rate among pediatric oncology patients with COVID-19 in LMIC. A systematic review of 21 studies examining COVID-19 outcomes in pediatric cancer patients reported an overall pooled mortality rate of 9%. Mortality varied significantly by income level in the region, with rates of 3% in HIC, 12% in upper-middle-income countries, and 13% in lower-middle-income countries (24). A multicenter international study involving 1,660 pediatric cancer patients from 91 hospitals across 39 countries examined the impact of COVID-19 on pediatric cancer care. Patients in LMICs face significantly higher mortality risks than those in HICs. The aORs for death at 30 and 90 days were 15.6 and 7.9 times higher, respectively, in LMICs (16). These results emphasize the importance of addressing global healthcare inequalities and enhancing oncology care systems, especially in LMICs, to mitigate disparities in outcomes for pediatric cancer patients during and after the pandemic.

Multivariate analysis revealed that male sex, cancer relapse, younger age, mechanical ventilation requirements, and specific malignancies, such as neuroblastoma, were significant predictors of mortality. These findings echo prior research showing that certain cancer types may carry higher risks of adverse outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in LMICs. Among pediatric cancer patients who died within 30 days of presentation, the most common cancer types were ALL and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. These findings indicate that hematologic malignancies are linked to higher mortality risks, highlighting the heightened vulnerability associated with these conditions during the pandemic (16). Patients with relapsed cancer, in particular, showed a substantially higher mortality risk, which can be explained by the weakened immune system due to previous chemotherapy cycles and bone marrow suppression. Neuroblastoma, a malignancy known for its aggressive nature and challenging treatment course, was also associated with poor outcomes in this study cohort. These findings emphasize the need for close monitoring and aggressive management strategies in high-risk groups, particularly those with relapsed cancer or specific malignancies known for poor prognosis. The absence of a direct association between COVID-19 positivity and mortality suggests that other factors, such as cancer type, stage, immune status, and treatment regimens, may be more influential in determining outcomes than the viral infection itself.

A study conducted at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center explored the impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (25). They found that certain patient characteristics and cancer treatments were associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and severe COVID-19 outcomes. Treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) is a significant predictor of severe COVID-19 outcomes, including hospitalization and the need for mechanical ventilation. This suggests that ICIs, which modulate the immune system, may increase susceptibility to severe infection. Unlike age and ICI treatment, chemotherapy or major surgery was not associated with a higher risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes in this study. This finding contrasts with earlier reports suggesting that cancer treatments may increase vulnerability to COVID-19 (26, 27), although this study did not find this correlation in its cohort (25). Patients with hematological cancer and metastatic lung cancer also appear to be at the greatest risk of severe complications and mortality due to COVID-19 (28).

It is crucial to account for the temporal sequence of events when interpreting the association between cancer relapse and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Relapses occurring before COVID-19 diagnosis likely reflect reverse causality, whereby immunosuppression induced by cancer relapse and its related treatments predispose patients to increased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection, rather than COVID-19 acting as a precipitating factor for relapse. Acknowledging this temporal framework is crucial for an accurate and nuanced understanding of the complex interactions between oncologic disease progression and COVID-19.

It is important to clarify that relapses occurring before the COVID-19 pandemic are not attributed to the effects of SARS-CoV-2. Instead, our findings suggest that patients who experienced relapse before contracting COVID-19 had an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection during their subsequent treatment course. This association likely reflects the greater degree of immunosuppression and healthcare exposure among patients with relapsed malignancies rather than a causal relationship between COVID-19 and prior relapse.

This study had several limitations. First, as a retrospective cohort study, it is subject to inherent biases, such as selection and information bias, due to reliance on existing medical records. Some relevant clinical or laboratory data may have been missing or inconsistently recorded. Second, although we performed multivariate regression analyses to adjust for key confounders (e.g., age, sex, underlying malignancy, and treatment variables), residual confounding from unmeasured or unknown factors may still be present. Third, the single-center design and relatively small number of COVID-19-positive pediatric oncology patients limit the generalizability of our findings to other settings and populations. Finally, a precise temporal alignment between key clinical events, such as cancer diagnosis, relapse, and death, is lacking. This limitation restricts our ability to establish causal relationships between COVID-19 infection and subsequent outcomes (we could not reliably determine whether the deaths were directly attributable to COVID-19, underlying malignancy, treatment complications, or a combination of these factors).

Although our analysis identified associations between certain risk factors and adverse outcomes, the retrospective design and timing of data collection precluded definitive causal conclusions. We addressed potential confounders by including relevant covariates in our statistical models and conducting sensitivity analyses where feasible. Future multicenter prospective studies with larger sample sizes and standardized data collection are needed to validate our findings and minimize bias.

5.1. Conclusions

In this cohort of pediatric oncology patients, a 15% mortality rate was observed among those with COVID-19. However, after adjusting for confounding factors, COVID-19 was not an independent predictor of increased relapse or mortality. These findings suggest that while COVID-19 poses a risk to this vulnerable population, its direct impact on relapse and mortality may be less significant than initially expected by researchers. Ongoing surveillance and further multicenter studies are needed to better understand the long-term and indirect effects of COVID-19 in pediatric oncology.