1. Background

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a widespread health problem in pediatrics and remains a common global cause of morbidity among children (1). It is one of the most prevalent infectious diseases with considerable mortality due to respiratory failure and multi-organ involvement, necessitating frequent intensive care interventions (2). Pneumonia attributable to severe respiratory tract infections in children presents with a sudden onset, swift progression, and significant mortality rates. It is associated with the highest levels of hospitalization and mortality among children aged under 5 years (3).

Multiple tests exist to determine the bacterial cause of CAP, yet each has its limitations. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and pleural fluid cultures are both sensitive and specific for identifying bacteria; however, their collection is invasive and rarely indicated. Testing via sputum and nasopharyngeal swabs fails to distinguish between pathogens that colonize the upper respiratory tract (URT) and those responsible for lower respiratory tract infections. Additionally, blood cultures display a sensitivity range of 0 - 14% because bacteremia is uncommon (4).

The most common etiological agent of bacterial pneumonia is Streptococcus pneumoniae, and the colonization of the URT is regarded as a necessary condition for the subsequent infection of the lower respiratory tract (5). To accurately diagnose patients with genuine pneumococcal pneumonia, it is crucial to differentiate between colonization and infection. Considering a cut-off based on PCR may prove to be beneficial (6). Previous studies indicate that children with pneumonia may have higher pathogen loads in the URT than those without pneumonia. Nonetheless, the load of bacteria varies in different studies and across different pathogens (7).

The autolysin N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase, which is encoded by the lytA gene, is important in the pathogenesis of pneumococci and has potential as a target gene for the molecular diagnosis of pneumococcal diseases (8, 9). Former research has indicated a correlation between the load of pneumococcal colonization in the URT and the occurrence of pneumococcal pneumonia disease. However, data about children remains rare. Investigations involving pediatric patients have demonstrated that increased colonization density relates to alveolar involvement and consolidation observed in chest X-rays (10).

Since pneumonia is a prevalent disease among children, it is crucial to diagnose it early, distinguish between bacterial and non-bacterial origins, and identify pathogenic colonization. This differentiation is essential for the prompt administration of necessary antibiotics while preventing the use of unnecessary ones. Research conducted in adult populations and various international contexts (5-7) indicates that assessing bacterial load through nasopharyngeal PCR can support making these distinctions.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to determine the load of pneumococci in patients and carrying children and compare them by determining the cycle threshold (CT) cut-off.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Setting

In this case-control study, the case population (patients) included 57 children with signs and symptoms of pneumococcal pneumonia, and controls were 102 healthy children under 18 years old from Mofid Children’s Hospital in Tehran, Iran, with positive results for S. pneumoniae PCR. The nasopharyngeal swabs of both groups were prepared and immediately transferred to the laboratory of the Pediatric Infections Research Center (PIRC) and stored at -80°C. The demographic and laboratory information of patients was collected from their records.

3.2. DNA Extraction and Real-time PCR

A DNA extraction kit (SIMBIOLAB, Iran) was used for DNA extraction from samples in both groups. The lytA gene was selected as a target gene to detect S. pneumoniae. The primer sequence was: Forward: 5’-CCATTATCAACAGGTCCTACC-3’ and reverse: 5’-TAAGAACAGATTTGCCTCAAG-3’ (11) with a 187 bp product size, and the PCR program was explained previously (11). Briefly, primary denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, 35 cycles of amplification with denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 58°C for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. An internal positive control of PIRC was used as a positive control for the PCR process. The 1,025-bp amplicon is the product of the NF-NR primers (universal bacterial primers) and was used as an extraction control in this study (12).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Using descriptive and inferential statistical methods, variables were described, and hypotheses and relationships were tested. In the descriptive statistics section, frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation were calculated using SPSS version 20. Univariate linear regression was employed to compare the positive PCR results in both groups and to assess the impact of disease severity on the CT value.

4. Results

In this descriptive study, a total of 57 patients were examined alongside 102 controls. The ages of the study population ranged from 3 months to 15 years old, with 52.9% of children being male, while the remaining percentage consisted of females. All extracted samples were validated by the positive results of PCR of internal control 16s rRNA by real-time PCR (RT-PCR). The overall colonization rate of S. pneumoniae in children under 5 years was 56% (89/159) in our study. The colonization rates in patients and healthy children were 59% and 53%, respectively.

In our study, the CT ratio ranged from 18.5 to 27.70 (mean: 24.85) in patients and from 15.28 to 30.30 (mean: 24.40) in the control group. Moreover, the chi-square test of pneumococcal positive PCR (CT values < 35) revealed that the positive PCR did not show any significant statistical difference between the patient and control groups (P > 0.05, Table 1).

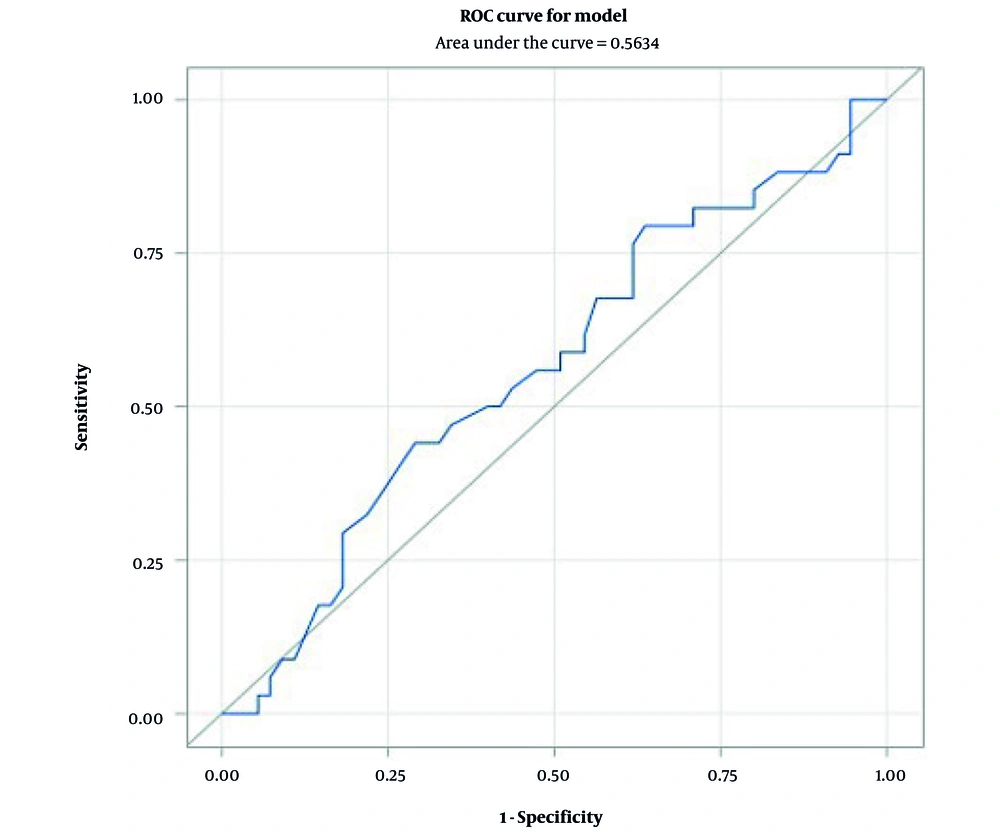

The receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis demonstrated that the sensitivity and specificity of the CT value, as well as the area under the curve (AUC), for predicting pneumococcal pneumonia were insufficient. Consequently, the CT value for identifying S. pneumoniae does not possess a strong predictive value for pneumococcal pneumonia (Figure 1).

The frequency distribution showed that 47% of patients with positive PCR had mild to moderate disease, while 53% had severe disease. Logistic regression analysis indicated that the odds ratio obtained for the CT of the positive pneumococcal pneumonia variable is 1.07. This suggests that the chance of bacterial pneumonia increases by 7% in children with a decrease of one-unit CT. However, this increase is not statistically significant according to logistic regression analysis (P = 0.31).

The results of univariate linear regression in the patient group with positive pneumococcus show that the P-value for disease severity is 0.13, indicating an effect on the CT variable. Children with severe disease had a 1.43 units lower CT than those with mild to moderate disease, which suggests a higher bacterial load in them (Table 2).

| Variable | Beta (Confidence Interval 80%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Disease severity (sever) | -1.43 | 0.13 |

5. Discussion

Streptococcus pneumoniae is one of the major causes of childhood mortality around the world (13, 14). Pneumococcal pneumonia can be a primary cause of mortality in young children, responsible for an estimated 294,000 deaths globally in children under the age of five. Colonization of the nasopharynx is recognized as a crucial step in the development of pneumococcal diseases (13-15).

In our study, the rate of S. pneumoniae colonization was higher in patients than in healthy children. The results of two studies in Sri Lanka and Thailand in 2020 (16) were similar to ours, showing that the rate of S. pneumoniae colonization in patients was higher than in healthy children. On the other hand, in another study in Thailand in 2020, S. pneumoniae colonization in the control group was reported to be higher than in the patients (17).

This difference in colonization may be due to various reasons, such as the time and season, the sampling method, differences in the socio-demographic backgrounds of the participants, geographical differences, and different age populations in the study groups. Some studies use the CT value obtained from RT-PCR for microorganism identification to differentiate between infection and colonization (18-20). Comparing the mean CT values between the patients and healthy children provides information on potential variations in S. pneumoniae colonization levels.

Nevertheless, our study did not reveal any significant differences in the mean CT values between the patients and controls (P > 0.05). Contrary to our results, numerous prior studies involving children have assessed pneumococcal colonization density as an indicator and molecular marker of pneumococcal pneumonia (10, 13, 17, 21, 22). However, some of these studies (17, 21, 22) precisely determine the bacterial load using quantitative RT-PCR, which can be very helpful but is expensive and requires a professional expert.

In an Ethiopian study, the average CT values were compared between patients infected by S. pneumoniae and control groups, acting as an indirect indicator of bacterial load. The results showed no statistically significant differences in the mean CT values between the two groups (P = 0.5) (20). Also, in the study by Vidanapathirana et al., no significant difference was observed in the amount of colonization of S. pneumoniae between sick and healthy children, even though this amount was higher in sick children (16).

The results of these studies (16, 20) are precisely aligned with ours, as they have been unable to find an appropriate cutoff to distinguish between colonized and infected children with S. pneumoniae.

The results of the study by Rouhi et al. showed that positive cases were categorized as follows: The CT ≤ 32 as infection, CT > 35 as colonization, and a grey zone was established for values between 32 and 35 (32 < X ≤ 35) in the detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii (18). This difference between our results and this study (18) can be attributed to the evaluation of different microorganisms in both studies. Perhaps the different load of P. jirovecii has a significant difference between colonized and infectious individuals. However, we did not observe these results in the load of S. pneumoniae in children.

Gronseth et al. worked on distinguishing Pneumocystis pneumonia from colonization in a heterogeneous population of HIV-negative immunocompromised patients. They reported that the median CT value was lower among patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia than among individuals without Pneumocystis pneumonia (P < 0.001), confirming higher fungal loads in those with clinical infection. Nevertheless, it was impossible to find an optimal CT cutoff value for distinguishing between patients and those with colonization because of the existing overlaps (19). In that study (19), a different microorganism was evaluated, similar to the study by Rouhi et al. (18), and they could determine the approximate cut-off, but their conclusion is similar to ours. They agree that the overlap of this data prevents the establishment of an accurate cutoff for CT value to distinguish between colonized individuals and those who are ill (19).

Considering the similar bacterial load observed in pediatric patients and carriers of S. pneumoniae, it may be feasible to establish a precise CT value distinguishing between patients and carriers. This can be achieved by quantifying the bacterial count through quantitative RT-PCR or by assessing the bacterial copy numbers based on the quantity of DNA extracted using instruments like Nanodrop.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicated that the bacterial load in colonized children with S. pneumoniae was high and comparable to that observed in patients suffering from pneumonia caused by the same bacterium. The CT value in RT-PCR is indirectly associated with the bacterial load. However, an accurate cut-off for the detection of S. pneumoniae in patients and carriers was not identified in our study.