1. Background

Pneumocystis jirovecii is an opportunistic yeast-like fungal pathogen that affects immunocompromised individuals, including children, HIV-infected patients, oncological patients, and transplant recipients (1). Transmission occurs through the inhalation of airborne spores. The clinical manifestations are often nonspecific, ranging from mild respiratory symptoms, such as cough and dyspnoea, to severe acute respiratory failure. Diagnosis is based on microscopic examination or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of respiratory samples, such as nasopharyngeal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage, pleural fluid, induced sputum, or gastric aspirate (2). Chest radiography commonly reveals bilateral interstitial infiltrates, whereas computed tomography (CT) may reveal ground-glass opacities and thickened septal lines. However, negative imaging results do not exclude P. jirovecii pneumonia, emphasising the importance of clinical suspicion in at-risk populations (3). The prognosis of patients with P. jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) without underlying comorbidities is generally favourable. However, HIV-infected individuals have a relatively high mortality rate, ranging from 10% to 20%, with some studies reporting even higher rates of 35% - 50%, especially in developing countries (4-6).

2. Objectives

We conducted this study to describe the clinical and demographic characteristics of paediatric patients with PCP and to report the diagnostic approaches used at our centre. We focused on assessing the clinical utility of real-time PCR-based detection of P. jirovecii in different clinical samples and describing the characteristics associated with positive cases.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sample Collection

This retrospective descriptive study analysed the written and electronic medical records of patients diagnosed with pneumonia and suspected P. jirovecii infection between November 2017 and September 2024 at the National Institute of Paediatric Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases in Slovakia. Patients were included if they presented with clinical signs of pneumonia (e.g., prolonged cough, tachypnoea, dyspnoea) and underwent diagnostic testing for P. jirovecii based on clinical suspicion, which was often heightened in infants with risk factors such as malnutrition, prematurity, and refractory respiratory symptoms.

3.2. Sample Collection and Molecular Analysis

A total of 277 samples were collected from these patients for analysis. DNA was extracted from the samples using a commercial kit according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by qualitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT PCR; AmpliSens®P. Jirovecii-screen-FRT PCR kit, Interlabservice, Czech Republic) on a Rotor-Gene 3000 instrument (Corbett Research Ltd., Australia). The majority of samples (224; 81%) were gastric aspirates, followed by bronchoalveolar lavage (19; 7%), sputum (16; 6%), laryngeal swabs (15; 5%), and pleural effusion (3; 1%). Owing to financial constraints and clinical considerations, each patient provided only one biological sample for the analysis. Consequently, patients with confirmed P. jirovecii infection via bronchoalveolar lavage did not undergo additional gastric aspirate collection for further testing.

3.3. Anamnesis and Clinical Findings

The primary data sources for medical history and clinical findings were the written and electronic medical records of the patients. To investigate potential risk factors for P. jirovecii RT-PCR positive cases and immunocompromising in the study cohort, we analysed anamnestic data. This data included demographic information (sex, age), social history (socioeconomic status, hygiene conditions, nutritional factors), perinatal history (gestational age, birth weight, mode of delivery, perinatal respiratory complications, congenital developmental defects), clinical history (chronic respiratory symptoms, recurrent respiratory infections, systemic corticosteroid therapy, anaemia of chronic disease, and coinfections with other pathogens), and immune parameters (immunophenotyping of lymphocyte and NK cell subtypes, humoral components of immunity). Socioeconomic and hygiene conditions were assessed based on structured information documented by the attending physician in the medical records, which included standardized fields for details on living conditions, family background, and exposure to environmental risk factors such as passive smoking.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were processed using descriptive statistics, with frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. For continuous variables, such as age, the median and range were calculated. Owing to the descriptive and retrospective nature of the study and the lack of a formal control group, no analytical statistical tests were performed to establish causality for risk factors.

4. Results

4.1. Demographics and Clinical Presentation

The study group of 277 patients, consisting of 171 boys (62%) and 106 girls (38%), ranged in age from 1.5 months to 17 years, with a median age of 9 months and a mean age of 24 months. A significant proportion of the patients, 162 (52%), were under 1 year of age, and 221 (80%) were under 3 years of age. The most affected group was infants, particularly premature infants with complex perinatal histories. These infants often belong to marginalised populations of Roma ethnicity with low socioeconomic status and are often fed formula milk, leading to poor weight gain and nutritional deficiencies. Among confirmed PCP cases, fourteen patients developed acute respiratory failure and required supplemental oxygen therapy and systemic corticosteroids. All patients who were positive for P. jirovecii by PCR met the established clinical and radiological criteria for PCP.

4.2. Proportion and Characteristics of Positive Biological Samples and Predominant Clinical Manifestations

Infection with P. jirovecii was confirmed in 36 (13%) of the 277 patients, comprising 19 boys and 17 girls. The ages ranged from 2 months to 2.5 years, with a significant proportion of 31 (86%) patients under 12 months of age. Among these 36 confirmed cases of PCP, the diagnosis was established from gastric aspirates in 29 patients (80%), followed by bronchoalveolar lavage in three patients (8%), laryngeal swabs in two patients (6%), and sputum in two patients (6%). This demonstrates the practical utility of gastric aspirates in our clinical setting for this specific patient group. Ct values (threshold cycles; single data points derived from real-time PCR amplification plots) ranging from 19 to 35 (median 28; SD 4.33; 95% CI: 26.3 - 29.2) were observed in the patient cohort, with the positivity limit for the employed kit set at Ct 35. In a single instance, a patient was deemed positive despite a Ct value slightly exceeding 35 (35.62), which was likely attributable to partial inhibition of the reaction. Conversely, the detection channel for P. jirovecii in this case exhibited an exponential amplification curve.

The predominant clinical presentation was prolonged respiratory deterioration with chronic cough and persistent refractory bronchoconstriction in 29 (81%) patients. Acute respiratory insufficiency requiring oxygen therapy and systemic corticosteroids was observed in 14 (39%) patients. Anaemia was also a common finding, affecting 20 (56%) patients.

4.3. Risk Factors and Coinfections

To investigate potential risk factors for RT-PCR confirmed P. jirovecii cases, several perinatal variables were analysed. The gestational age at birth was evaluated, revealing that 25 (69%) babies were born at term (37 - 40 weeks), 10 (28%) were slightly preterm (32 - 36 weeks), and 1 (3%) was very preterm (28 - 31 weeks). With respect to mode of delivery, 25 (69%) infants were delivered vaginally, 8 (22%) by caesarean section, 2 (6%) extramurally, and 1 (3%) by vacuum extraction. The birth weight was classified as normal (2500 - 4000 g) for 20 (56%) babies, low birth weight (1500 - 2499 g) for 11 (31%), very low birth weight (1000 - 1499 g) for 3 (8%), and excessive birth weight (> 4000 g) for 2 (6%). In terms of perinatal history, 9 (25%) patients had a history of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) that required mechanical ventilation, and 7 (19%) had congenital airway malformations, including laryngomalacia, tracheomalacia, cleft lip and palate, and bronchial stenosis. Congenital heart defects, involving pulmonary stenosis, patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defects, and left ventricular hypertrophy, were present in 4 (11%) patients. One patient had pulmonary hypertension. These data, including patient demographics, specimen types, and clinical presentations, are summarized in Table 1.

| Demographic Characteristics | Values a |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 19 (53) |

| Female | 17 (47) |

| Age | |

| Median (mo) | 9.5 |

| Range (mo - y) | 2 - 2.5 |

| ≤ 12 months | 31 (86) |

| > 12 months | 5 (14) |

| Specimen type | |

| Gastric aspirate | 29 (80) |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage | 3 (8) |

| Laryngeal swab | 2 (6) |

| Sputum | 2 (6) |

| Clinical presentation | |

| Prolonged bronchial obstruction | 29 (81) |

| Acute respiratory insufficiency | 14 (39) |

| Anemia | 20 (56) |

| Gestational age at birth (wk) | |

| Term (37 - 40) | 25 (69) |

| Preterm (32 - 36) | 10 (28) |

| Very preterm (28 - 31) | 1 (3) |

| Mode of delivery | |

| Vaginal delivery | 25 (69) |

| Caesarean section | 8 (22) |

| Extramural delivery | 2 (6) |

| Vacuum extraction | 1 (3) |

| Birth weight (g) | |

| Normal (2500 - 4000) | 20 (56) |

| Low (1500 - 2499) | 11 (31) |

| Very low (1000 - 1499) | 3 (8) |

| Excessive (> 4000) | 2 (6) |

| Perinatal history | |

| Infant RDS | 9 (25) |

| Congenital airway malformations | 7 (19) |

| Congenital heart defects | 4 (11) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (-) |

Abbreviation: RDS, respiratory distress syndrome.

a Values are expressed as No (%) unless indicated.

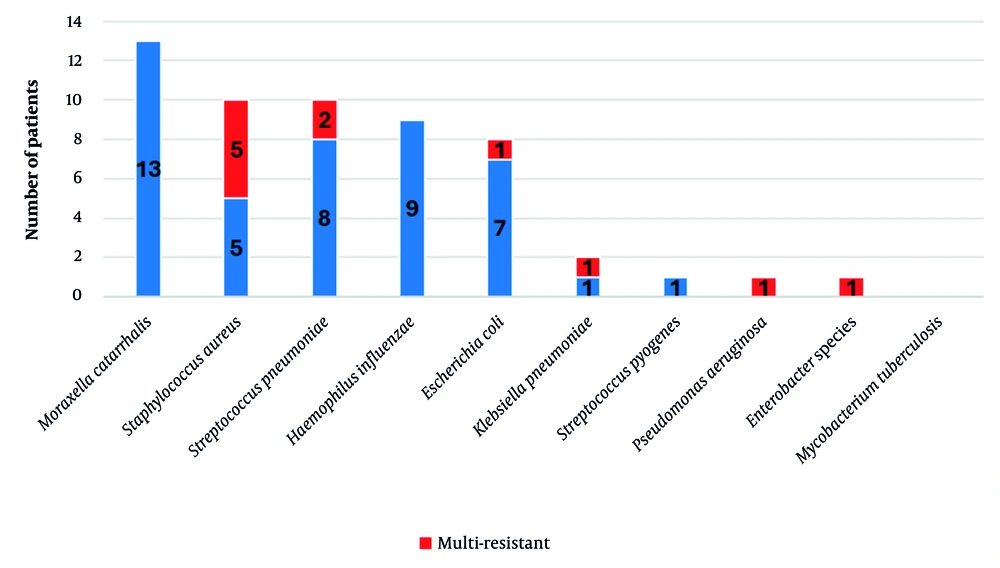

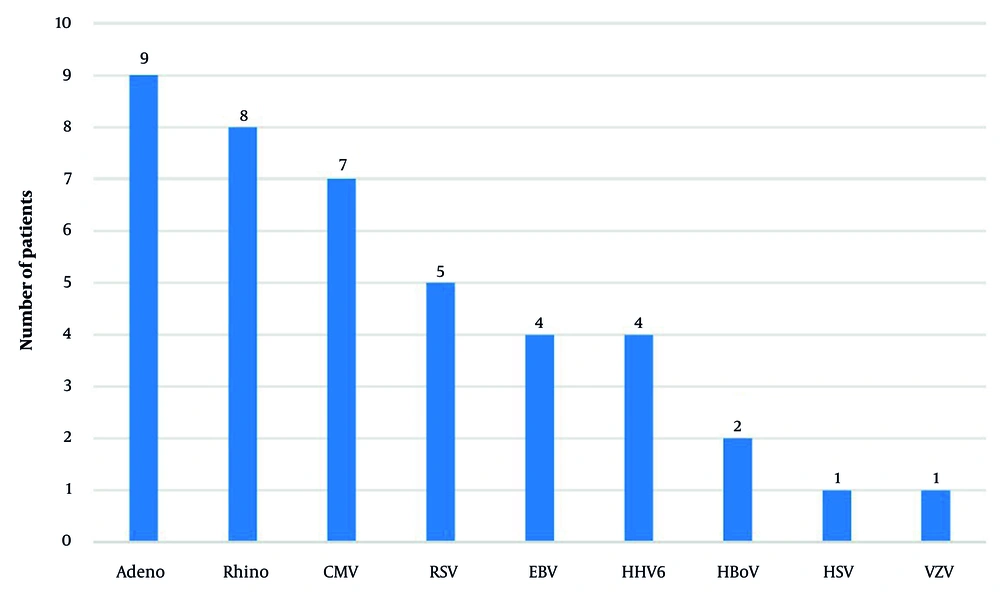

We also assessed the prevalence of other pathogens coinfecting patients with pneumocystosis from disease onset. Among the bacterial pathogens, Moraxella catarrhalis (36%; 13 patients), Staphylococcus aureus (28%; 10 patients, including 5 methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]), Streptococcus pneumoniae (28%; 10 patients), Haemophilus influenzae (25%; 9 patients), and Escherichia coli (22%; 8 patients) were identified most frequently. Two patients (6%) had coinfections with Klebsiella pneumoniae, while one patient (3%) each had infections with S. pyogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species (Figure 1). The following viral pathogens were detected: Adenovirus (25%; 9 patients), rhinovirus (22%; 8 patients), cytomegalovirus (CMV; 19%; 7 patients), respiratory syncytial virus (14%; 5 patients), Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus (6%; 11%; 4 patients each), bocavirus (6%; 2 patients), and herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (3%; 1 patient each) (Figure 2). Furthermore, 10 (28%) patients had Candida albicans infection, 3 (8%) had coinfection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and 2 (6%) had Chlamydia pneumoniae and Bordetella pertussis.

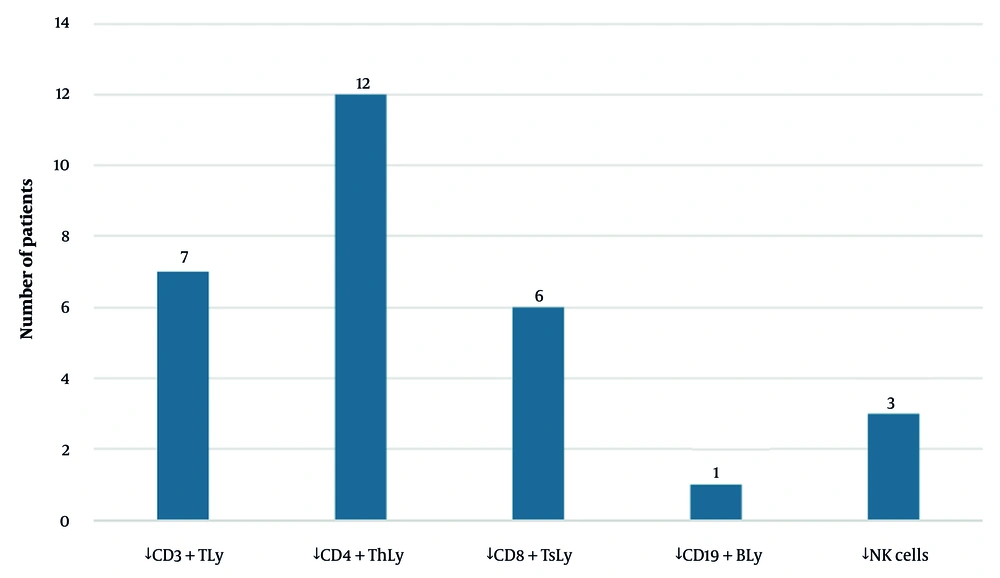

4.4. Immunological Evaluation

Furthermore, we assessed immunity in most patients. Hypogammaglobulinaemia was assessed in 92% of the patients (n = 33). A slight decrease in immunoglobulin G (IgG) was observed in 5 patients (14%), immunoglobulin M (IgM) in 4 (11%), and immunoglobulin A (IgA) in 3 (8%). IgG concentrations did not require substitution therapy in all but one patient. Cellular immunity was assessed in 75% of the patients (n = 27), with CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion in 12 patients (33%), CD3+ T lymphocyte depletion in 7 patients (19%), CD8+ T lymphocyte depletion in 6 patients (17%), CD19+ B lymphocyte depletion in 1 patient (3%), and NK cell depletion in 3 patients (8%) (Figure 3). Importantly, none of the positive patients had HIV infection, known cancer, or a history of transplantation. Two patients exhibited highly suspected innate immune disorders and, together with others, received further evaluation by an immunologist.

4.5. Socioeconomic Determinants

Among the 36 positive children with PCP, only two were not from marginalized populations of Roma ethnicity. The children's poor health, including skin lesions, malnutrition, and oral health issues, was likely associated with their adverse living conditions in a marginalized community, characterized by poverty, a lack of stimulation, solid fuel heating, passive smoking, and inadequate sanitation.

5. Discussion

This study describes the clinical and demographic profile of 36 paediatric patients with PCP in a non-HIV context, highlighting a strong association with socioeconomic deprivation and demonstrating the high clinical utility of gastric aspirates for diagnosis in this population. Publications on paediatric PCPs are limited worldwide. Early studies, such as the 1977 study by Chan and Feldman, examined lung and gastric aspirate samples from 13 paediatric cancer patients (aged 1 - 16 years) via microscopic techniques (7). Although we did not perform a microscopic examination, our positive cases were not simultaneously evaluated for both lung and gastric aspirates via PCR. Treatment was started upon a positive result from any single sample. A recent study evaluated the clinical utility of PCR on a larger number of samples from various respiratory sources from children (induced sputum, tracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage) over a 21-year period. Among the 110 P. jirovecii-positive samples obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage, 14 were confirmed cases of PCP, 65 were probable cases on the basis of clinical criteria, and 31 were cases of non-Pneumocystis pneumonia (8). Our study lacked a control group. A French study evaluated PCR samples from 379 hospitalized children under 3 years of age and identified 32 positive samples, mainly from bronchoalveolar lavage and nasopharyngeal aspirates (9). Indian researchers published a study that examined 143 samples from April 2005-June 2006, including two negative gastric aspirate samples. A total of 14 patient samples tested positive (10). Dunbar et al. proposed a CT value threshold of ≤ 28.5 - 30 for probable PCP in HIV-infected patients (11). In our cohort, a substantial proportion of patients (61%) exhibited a CT value of the PCR method below this threshold.

In February 2019, Japanese researchers reported the first two paediatric cases of PCP, which were diagnosed via gastric lavage (12). Prior to this, no cases in which this diagnostic method was used had been reported. In particular, our centre confirmed its first PCR-positive case from a gastric aspirate in March 2018. Among our 36 PCP patients, 10 were preterm, and one was very preterm. Eleven patients had low birth weights, and three had very low birth weights. Congenital airway malformations were present in seven patients, whereas congenital cardiac malformations were identified in four patients. The vast majority of the 36 children with PCP were from marginalized Roma populations. In Slovakia, Roma ethnicity constitutes approximately 8 - 10% of the population and is overrepresented among childhood tuberculosis cases (13). None of our patients who tested positive for P. jirovecii had tuberculosis. Multiple factors contribute to the increased incidence of selected infectious diseases within Roma communities, including generational poverty, low educational attainment, smoking, stigmatization of the disease, and distrust of healthcare systems (14).

A recent retrospective study evaluated bronchoalveolar lavage and tracheal aspirate samples collected from children over a 27-year period (1989 - 2016). A total of 25 positive cases were identified, 24 originating from bronchoalveolar lavage samples and one from a tracheal aspirate (15). Direct antigen immunofluorescence staining was positive in 17 patients, cytology was positive in six patients, and RT PCR was positive in two patients. CMV was the most frequently identified co-infecting agent, detected in 26% of patients. In our study, CMV was identified as a co-infecting agent in 19% of patients, whereas adenovirus (25%) and rhinovirus (22%) were observed more frequently. In Mozambique, Streptococcus pneumoniae was the predominant bacterial coinfection in 14% of 57 children with PCP. This bacterium was also the most common co-infection in 10 (28%) of the children studied (16). With respect to viral infections, rhinovirus was significantly predominant in 31% of the Mozambican children. In our study, adenoviruses were the most common (25%), followed by rhinoviruses (22%). The severe inflammatory response and bronchoconstriction seen in our patients are critical components of the pathology. While the specific mechanisms were not the focus of this study, related research into inflammatory pathways in acute lung injury offers valuable context, such as the investigation of PARP-1 and HDAC3 pathways in LPS-induced lung injury (17).

Researchers from China identified fungal infections, primarily C. albicans and Aspergillus species, in 13 (21%) of 42 children (18). In particular, the rate of C. albicans infection observed in this paediatric population exceeded that reported in adult studies (19-21). This finding underscores the importance of considering fungal coinfection, particularly in children without HIV coinfection with poor response to PCP therapy. Consistent with these observations, our cohort of non-HIV paediatric patients revealed a substantial prevalence of C. albicans infection, affecting 10 (28%) of the 36 individuals. The risk of fungal co-infections in severe respiratory illness, particularly with P. jirovecii, is a significant clinical concern, as illustrated by case reports of fatal co-infections with other fungi, such as Aspergillus latus (22).

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia predominantly affects children with compromised cellular immunity (23). Similarly, a previous study investigating cellular immunity in children with PCP reported significant reductions in CD4+ lymphocyte counts and increases in CD8+ lymphocyte levels (CD4/CD8 ratio 95% confidence interval, 0.849 - 0.955) (18). The CD4/CD8 ratio has emerged as a promising biomarker for predicting and diagnosing PCP in non-HIV populations. Our assessment of cell-mediated immunity in these patients corroborated these findings, with a marked decrease in CD4+ lymphocyte proportions observed in 12 (33%) of 36 individuals. None of the 36 patients with PCP had HIV infection, malignancy, or a history of transplantation. Two patients were suspected to have primary immunodeficiency disorders, 33% exhibited significant decreases in CD4+ lymphocyte counts, 19% had decreased CD3+ lymphocyte counts, and 17% had decreased CD8+ lymphocyte counts. Furthermore, immunologists have investigated the underlying immune defects in these patients, but the results remain unclear.

We acknowledge that the relatively small sample size and absence of a control group of healthy infants may be considered major limitations of this study. Conducting semi-invasive diagnostic investigations, such as gastric aspirate sampling or bronchoalveolar lavage, in healthy infants presents significant challenges. Furthermore, a key limitation of our study design was that each patient provided only one type of biological sample for analysis. Because paired samples (e.g., gastric aspirate and bronchoalveolar lavage from the same patient) were not collected, it was not possible to directly compare the diagnostic sensitivity of real-time PCR across these different sample types. Differences in test positivity may be due to variations between patient groups rather than the sample type. For instance, the decision to perform a more invasive procedure, such as bronchoalveolar lavage, may have been reserved for patients with more severe or atypical presentations, which could introduce a selection bias. Therefore, our study does not aim to establish the superiority of one method over another but rather to highlight the practical value of gastric aspirate as a frequently successful, minimally invasive diagnostic tool in a real-world clinical setting. However, given the duration of the study, the number of samples analysed was substantial and represents the highest number of positive PCR results in paediatric patients reported in the literature to date, with up to 29 positive gastric aspirate samples. Although bronchoalveolar lavage is the ideal method for diagnosing PCP, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage is a high-risk invasive procedure in young children, particularly those with underlying conditions, airway obstruction, or oxygen dependency. Although sputum collection is a suitable alternative, it is challenging in children under 2 years of age. However, sputum samples obtained during respiratory physiotherapy may prove valuable. Laryngeal swabbing, a simple, rapid, and noninvasive technique, offers limited sensitivity for detecting P. jirovecii. The key findings and clinical implications are summarised in Table 2.

| Finding | Implication |

|---|---|

| PCP can occur in immunocompromised infants, particularly those from marginalized and impoverished populations. | Increased awareness and consideration of PCP is needed for this population. |

| Gastric aspirate can be a valuable alternative biological source for direct PCR testing for PCP in young children. | Gastric aspirate can be used for minimally invasive diagnosis of PCP. |

| Early diagnosis and treatment of PCP are crucial for improving outcomes in affected children. | Healthcare providers should prioritize prompt diagnosis and treatment of PCP in infants. |

| Malnutrition, poor sanitation, tobacco smoke exposure, and exposure to combustion fumes may contribute to secondary immunodeficiency and increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections, including PCP. | Addressing these risk factors may help prevent PCP in vulnerable populations. |

| A low CD4/CD8 ratio could be a useful diagnostic and prognostic tool for PCP in non-HIV-infected individuals. | This ratio may aid in identifying and managing PCP in infants. |

Abbreviation: PCP, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

5.1. Conclusions

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia should be considered in infants, particularly those of marginalised populations with poor social status, inadequate hygiene, malnutrition, and risky perinatal history, as well as premature infants with low birth weight and immunodeficiency, especially before the age of two. The early development of the immune system is influenced by various exogenous factors, including nutrition, environmental exposure, and infection. These findings suggest that secondary immunodeficiency in toddlers and infants from marginalised communities may predispose them to significant colonisation by P. jirovecii and subsequent disease. The diagnosis of PCP is challenging, costly, and limited in many settings. While our study cannot make definitive claims about the comparative sensitivity of different methods, it demonstrates that PCR-based analysis of gastric aspirates is a clinically useful and effective diagnostic method for this population. In our study, securing a diagnosis through this approach and initiating appropriate treatment led to significant clinical improvement, resolution of bronchial obstruction, and nutritional recovery in the affected infants.