1. Background

Inter-individual variation in drug response has always been a concern in the treatment of patients. This issue becomes particularly critical in immunocompromised individuals, such as cancer patients receiving voriconazole for the management of invasive fungal infections (IFI) (1). Drug-drug interactions, genetic polymorphisms, physiological features, and pathological characteristics may result in sub- or supratherapeutic serum voriconazole trough concentrations (2). Among these, genetic variability is a major determinant, highlighting the importance of pharmacogenomics and the clinical use of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). Genetic variations in drug-metabolizing enzymes profoundly affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of different medications (3). CYP2C has four subfamily genes located on the 10q23.33 chromosome (4). The Cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily C, polypeptide 19 (CYP2C19) enzyme plays an essential role in the metabolism of various types of drugs (5). It is highly polymorphic, and multiple genetic variations or alleles can be present in the population. According to the Pharmacogene Variation Consortium (PharmVar, www.pharmvar.org), more than 39 different alleles have been identified as of 2022 (6-8).

Among the numerous genetic variations found in the population, the most studied alleles with single-base substitutions are *2, *3, and *17. The *2 and *3 alleles are loss-of-function variants that markedly reduce CYP2C19 activity (4), whereas the *17 allele is a gain-of-function variant that may lead to lower drug exposure and suboptimal treatment outcomes (4, 9). The wild-type (functional) allele of CYP2C19 is CYP2C19*1 (10). Managing IFIs in patients with hematological malignancies presents a significant challenge, especially in pediatric cases. In addition to genetic variation, factors such as drug–drug interactions, hepatic dysfunction, concurrent anticancer therapies (e.g., vincristine), graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), and the use of immunosuppressants further complicate antifungal drug exposure and efficacy (11, 12). CYP2C19 polymorphisms can substantially alter voriconazole pharmacokinetics, leading to differences in serum trough concentrations and clinical outcomes. Consequently, dose adjustments and the use of TDM are often necessary. Understanding the prevalence and impact of these alleles in pediatric patients with malignancies is crucial for personalized medicine. This approach enhances treatment strategies by optimizing efficacy and reducing adverse effects.

According to a study conducted in some Middle Eastern countries among healthy individuals, the frequency of the *17 allele was approximately 0.2%, with the *3 allele absent in Tunisian participants (13). There is limited information available on the genotyping of CYP2C19 in cancer patients. Any genetic variations could potentially alter treatment pathways and even put their lives at risk. Given the high stakes of antifungal therapy in these patients, any genetic variations may significantly alter treatment pathways, underscoring the urgent need for integrating pharmacogenetic testing and TDM into clinical protocols.

2. Objectives

The objective of this study was to identify CYP2C19 variants in pediatric cancer patients at a tertiary oncology center in Shiraz, Iran, to provide personalized dosing recommendations for critical medications such as voriconazole.

3. Methods

3.1. Patients, Sample Collection, and Ethical Approval

The Ethical Committee at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences approved the study (IR.SUMS.REC.1398.247). This cross-sectional study adhered to the guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians. Eligible participants were pediatric patients (< 18 years) with confirmed malignancies (one 20-year-old patient treated under pediatric protocols was also included) between February 2022 and March 2023. Exclusion criteria included uncertain or non-malignant diagnoses. The sample size was determined by the number of eligible patients presenting during the study period. Convenience sampling was used to collect blood specimens before the administration of any medication, using EDTA-containing tubes. Demographic data and patients’ outcomes were collected from the electronic medical record information system. Patients lacking a definitive diagnosis or those with excluded malignancy diagnoses were excluded from the study.

3.2. DNA Extraction and Molecular Approach

Genomic DNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions (Sinacolon, Iran). Genotyping was performed using polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP), as described by Sim et al. and Ikebuchi et al. (9, 14). Primers used for the amplification of the alleles included CYP2C19*3 primers: 5′-AACATCAGGATTGTAAGCAC-3′ (forward), 5′-TCAGGGCTTGGTCAATATAG-3′ (reverse); CYP2C19*17 primers: 5′-GCCCTTAGCACCAAATTCTC-3′ (forward), 5′-ATTTAACCCCCTAAAAAAACACG-3′ (reverse) (9). Briefly, the PCR reaction mixture comprised 2 µL genomic DNA, 12.5 µL Taq DNA polymerase master mix RED with 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Ampliqon, Denmark), 0.5 µM of each primer, and 8.5 µL double distilled water in a total volume of 25 µL. The PCR conditions included initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 34 cycles of 95°C for 45 seconds, 60°C for 45 seconds, 72°C for 45 seconds, and a final extension of 7 minutes at 72°C. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose (CinnaGen, Iran) gel and visualized by UV. The 119-bp and 473-bp bands were detected for the *3 and *17 alleles, respectively. The BamHI or LweI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) enzymes were used according to the manufacturer's instructions for restriction fragment polymorphism of the *3 and *17 alleles, respectively. The digested PCR products were separated using a 2.5% agarose gel. All tests were performed in duplicate. Positive and negative controls were included in each run of tests.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were collected and analyzed using Stata, version 17. Statistical analysis was performed to determine the prevalence of each allele in the study population and to assess any associations between specific alleles and patient outcomes. Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was applied to evaluate associations between genotypes and clinical variables.

4. Results

Overall, out of the 78 patients enrolled, four were excluded due to incomplete data, resulting in 74 patients being assessed for CYP2C19 genotyping. Of these, 43 patients (58.1%) were male, with an average age of 8 ± 4 years (ranging from 1 to 20 years). During the study period, 7 patients (9.5%) passed away. The demographic, clinical, and outcome characteristics of the patients, categorized by their genotype, are detailed in Table 1.

| Variables | Genotype 1/1 | Genotype 1/17 | Genotype 17/17 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Pro. | 95% Conf. Interval | N | Pro. | 95% Conf. Interval | N | Pro. | 95% Conf. Interval | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 25 | 0.64 | (0.48, 0.78) | 12 | 0.31 | (0.18, 0.47) | 2 | 0.05 | (0.01, 0.19) |

| Female | 23 | 0.79 | (0.60, 0.90) | 5 | 0.17 | (0.07, 0.36) | 2 | 0.03 | (0.004, 0.21) |

| Age group (y) a | |||||||||

| 0 - 5 | 13 | 0.68 | (0.45, 0.85) | 6 | 0.31 | (0.15, 0.55) | 0 | 0 | - |

| 6 - 10 | 20 | 0.71 | (0.52, 0.85) | 8 | 0.28 | (0.15, 0.48) | 0 | 0 | - |

| > 11 | 14 | 0.82 | (0.57, 0.94) | 1 | 0.06 | (0.007, 0.33) | 2 | 0.12 | (0.03, 0.37) |

| Disease type | |||||||||

| Leukemia | 29 | 0.70 | (0.53, 0.81) | 11 | 0.26 | (0.15, 0.42) | 2 | 0.05 | (0.01, 0.17) |

| Lymphoma | 5 | 0.71 | (0.32, 0.93) | 2 | 0.28 | (0.07, 0.68) | 0 | - | - |

| Aplastic anemia | 6 | 0.86 | (0.40, 0.98) | 1 | 0.14 | (0.02, 0.59) | 0 | - | - |

| Others | 8 | 0.66 | (0.37, 0.87) | 3 | 0.25 | (0.08, 0.56) | 1 | 0.08 | (0.01, 0.42) |

| IMI | |||||||||

| Yes | 8 | 1.00 | - | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - |

| No | 40 | 0.66 | (0.54, 0.77) | 17 | 0.28 | (0.18, 0.41) | 3 | 0.05 | (0.01, 0.15) |

| Outcome | |||||||||

| Alive | 43 | 0.70 | (0.6, 0.80) | 16 | 0.26 | (0.16, 0.39) | 2 | 0.03 | (0.008, 0.12) |

| Dead | 5 | 0.71 | (0.32, 0.93) | 1 | 0.14 | (0.02, 0.59) | 1 | 0.14 | (0.02, 0.59) |

Abbreviations: N, number of cases; Pro, proportion; IMI, invasive mold infections.

a The calendar age at diagnosis.

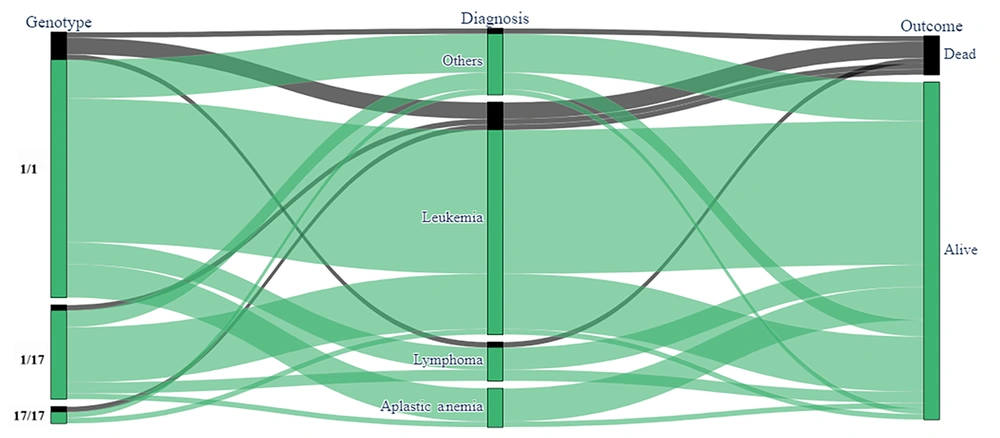

The frequency of CYP2C19*17 and CYP2C19*3 alleles were 16.2% (12/74) and 1.3% (1/74), respectively. Genotypes in order of frequency were *1/*1 (69%), *1/*17 (27%), *17/*17 (2.7%), and *1/*3 (1.3%, Table 2). A majority (51 patients, 96%) were homozygous for the wild-type allele in both exon 5 and the 5' flanking region (*1/*1), 1.3% (1 out of 74) were heterozygous in exon 4 (*1/*3), and a total of 20 patients (27%) were heterozygous in the 5' flanking region (*1/*17). In total, 2 patients (2.7%) exhibited heterozygosity in the 5' flanking region (*17/*17). Acute lymphoblastic leukemia was the most common underlying disease, accounting for 47.3% of cases. No significant correlation was found between the type of cancer or patient outcomes and the tested CYP2C19 genotypes. Given a P-value threshold of less than 0.2 and confidence intervals with an upper bound of less than 10, it was not possible to establish a definitive model. The distribution of patients’ CYP2C genotypes, categorized by diagnosis and outcome, is depicted in Figure 1.

| Genotypes | Expected Phenotype | Value |

|---|---|---|

| *1/*1 | Normal metabolizer | 51 (69) |

| *1/*17 | Rapid metabolizer | 20 (27) |

| *17/*17 | Ultra-rapid metabolizer | 2 (2.7) |

| *1/*3 | Intermediate metabolizer | 1 (1.3) |

| Total | - | 74 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

Voriconazole, a drug extensively metabolized by CYP2C19, is particularly affected by its polymorphisms, which can significantly alter drug metabolism (15-17). In the current study, 22 (29.7%) patients were identified as rapid/ultra-rapid metabolizers, which may result in subtherapeutic drug levels and potential treatment failure. The consequences of therapeutic failure with voriconazole are potentially life-threatening. Conversely, patients classified as poor metabolizers could experience elevated drug concentrations, heightening the risk of adverse effects or treatment failure. Extensive metabolizers might require increased dosages to achieve therapeutic efficacy. Notably, in this genotyping study, no patients were categorized as poor metabolizers, and only one was identified as an intermediate metabolizer. CYP2C19 genotyping is instrumental in forecasting drug-drug interactions, including the interaction between voriconazole and tacrolimus (18). Since blood samples were collected before the commencement of induction chemotherapy, the specific anticancer drugs administered were not documented. Overall, CYP2C19 genotyping is pivotal in tailoring drug therapy to individual needs, thereby enhancing patient care and outcomes. The frequency of CYP2C19 genotypes exhibits variation among diverse populations and ethnic groups. In our study, the genotypes appeared in the following order of frequency: *1/*1 (69%), *1/*17 (27%), *17/*17 (2.7%), and *1/*3 (1.3%) (19). There is limited data regarding CYP2C19 genotypes in pediatric oncology patients. In a study on a healthy Iranian population, the frequency of CYP2C19*17 was 21.6%, and allele *3 was not reported (20). Research by Azarpira et al. identified a 1% frequency of the CYP2C19*3 allele in healthy individuals from southern Iran (21). In Caucasian populations, the CYP2C19*17 allele is more common, occurring at a rate of 22%, while the *3 allele is found in less than 1% of the population (1). A study by Sameer et al. in the Gaza Strip in 2009 reported a CYP2C19*3 allele frequency of 0.96% among children with hematological malignancies (22). Wang et al. found allele frequencies of 3.8% for CYP2C19*3 and 0.5% for CYP2C19*17 in immunocompromised children (23). In our study, the frequencies of CYP2C19*17 and *3 were 16.2% and 1.3%, respectively, exceeding those reported by Sameer et al. and Wang et al. (22, 23). Also, the observed heterozygosity for allele *17 matched the expected heterozygosity, whereas for allele *3, it was lower than anticipated. In this study, the majority of patients were identified as normal metabolizers (51/69). Research from the United States has highlighted the CYP2C19 phenotype as a key risk factor for infection in rapid or ultra-rapid metabolizers compared to normal metabolizers (24). Children with malignancies are particularly susceptible to infectious diseases, notably fungal infections. An analysis of pediatric patients on voriconazole for aspergillosis revealed significant impacts of CYP2C19 gene polymorphisms on drug metabolism (25). Ruijters et al. observed a high mortality rate of 61.5% in aspergillosis patients, underscoring the critical nature of any treatment interference on patient survival (26). Our study did not reveal a significant link between cancer types and CYP2C19 genotypes. However, another study identified an association with childhood cancer development (27), and Wang et al.'s meta-analysis suggested poor metabolizer genotypes may contribute to cancer susceptibility in Asians (23). The difference may be explained by the limited number of patients or the specific genotypes tested.

Our study had several limitations. This was a cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital with a limited number of pediatric patients, so the results may not represent other populations. Genetic polymorphisms of other CYP2C19 alleles were not analyzed. We only tested selected CYP2C19 variants and did not fully account for other factors like chemotherapy, liver function, or co-medications that could affect drug metabolism. Fungal infections were not included as part of the study design or data collection; hence, our results cannot be generalized to outcomes related to invasive fungal disease. Further research is essential to validate our results and to explore the impact of additional covariates not considered in this study.

5.1. Conclusions

The CYP2C19*17 allele was notably prevalent among the patients studied, which may result in rapid (heterozygous) or ultra-rapid (homozygous) metabolizer phenotypes, leading to subtherapeutic drug levels in clinical settings. Applying CYP2C19 genotyping for these patients is crucial for determining the appropriate drug dosage to achieve therapeutic concentrations and prevent toxicity, especially during the initial treatment phase.