1. Background

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when pathogens develop the ability to defeat the drugs intended to kill them. It is a serious problem, leading to 5 million deaths per year globally and 35,000 deaths in the U.S.A. (1). The term "Multi-Drug Resistance (MDR)" refers to a microorganism that is not susceptible to at least one agent in three or more categories of antimicrobial agents. One of the well-known pathogens capable of developing MDR species is Acinetobacter baumannii (2). Acinetobacter baumannii is a major cause of nosocomial infections and has an exceptional capacity to develop resistance to antibiotics. To date, 45 resistance genes have been identified in A. baumannii. These MDR A. baumannii strains can circulate in hospitals and infect patients (3). Ventilator-associated pneumonia and bloodstream infections are the most common nosocomial infections reported in relation to this bacterium. Treatment of MDR A. baumannii infections is often complex because it can be resistant to all systemic antibiotics, including carbapenems and even polymyxins. In these cases, the only alternative left is combination therapy, but unfortunately, the available options are narrowing as this germ develops more MDR forms (4). There are several virulence factors enabling A. baumannii to be resistant to available antibiotics, which, according to the results of previous studies, can be classified into three groups: Outer membrane components, nutrient acquisition factors, and community interaction factors (3). Among these categories, the "outer membrane components" include a wide range of factors existing or secreted outside of the bacterial membrane, fighting against antibiotic agents. They include the following factors: Lipopolysaccharide biotinylated (LpsB), outer membrane protein A (OmpA), capsule (Cap), phospholipase (PLD), and type VI secretion system (T6SS) (5-7).

The LpsB expression is related to osmotic resistance and permeability defects of the outer membrane, thereby leading to antibiotic resistance. Although low expression of porin OmpA has been attributed to antibiotic resistance in A. baumannii, the Cap around its bacterial surface (Cap gene) is one of the innate mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in A. baumannii. Some studies of antibiotic-resistant isolates of A. baumannii have identified a linkage with PLD genes in these strains. The valine-glycine deletion repeats vgrG gene, a part of the T6SS, is regarded as a critical virulent factor of A. baumannii, leading to decreased resistance to some antibiotics like chloramphenicol (8).

2. Objectives

To the best of our knowledge, there is little information to date in Iran concerning the detection of genes related to the groups of virulence factors of MDR A. baumannii (9). Therefore, this study aimed to determine the antibiotic-resistant patterns, phenotypic and molecular patterns of antibiotic resistance, and the identification of some virulence genes in MDR strains of A. baumannii.

3. Methods

3.1. Bacterial Isolation and Identification

In this study, 50 A. baumannii clinical samples were collected from patients in 10 cities in Iran over one year. The samples were gathered from the ICU, neurology, nephrology, gastrointestinal, surgery, orthopedics, internal, trauma, burn, pediatrics, CCU, NICU, OICU, and cardiac wards of hospitals located in Tehran, Sanandaj, Esfahan, Hamedan, Tabriz, Mashhad, and Zahedan in Iran. Samples were collected from blood (n = 9), wound (n = 1), urine (n = 3), CSF (n = 5), bronchi (n = 4), IV catheter (n = 1), trachea (n = 25), double lumen central venous catheter (n = 1), and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) (n = 1).

3.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Clinical isolates collected from hospitalized patients; (2) phenotypic identification as A. baumannii by microbiological and biochemical assays; (3) molecular confirmation by detection of the blaOXA-51 gene using PCR; (4) isolates meeting the definition of MDR, i.e., resistance to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) Duplicate isolates from the same patient; (2) non-baumannii isolates; (3) samples with inadequate clinical or laboratory data.

The collected samples were stored at the Pediatric Infections Research Center, Research Institute of Children's Health, Tehran, Iran. Initially, we removed the samples from the deep freezer, which was maintained at a temperature of -80°C. Identification and confirmation tests, such as checking the morphology of bacterial colonies and using biochemical tests like oxidase and triple sugar iron agar (TSI), were performed.

Samples were cultured on specific blood agar and MacConkey agar (Merck, Germany) and then incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. The gram-negative bacilli were carefully monitored for further biochemical tests, including motility, sugar fermentation, citrate utilization, growth on TSI agar, and the IMVIC (Methyl red, Indole, Citrate, and Voges Proskauer) test. Definitive identification of A. baumannii isolates was achieved using a PCR method with primers specific to the blaOXA-51 gene (10).

3.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

After confirming the samples of A. baumannii, we tested them to determine the MDR ones using the Kirby-Bauer agar disk diffusion method on a Muller-Hinton agar culture (Merck Co., Germany). Antibiotic susceptibility results were interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (Institute, 2016) (11). The evaluation of the susceptibility rate to colistin in MDR A. baumannii isolates was done using a microdilution method. Finally, the results were interpreted based on the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (CLSI) breakpoints (resistant, ≥ 4 mg/L; intermediate, ≥ 2 mg/L) (11). "Multi-Drug Resistance (MDR)" is considered when the microorganism is not susceptible to at least one agent in three or more categories of antimicrobial agents (12).

Antibiotic disks (Mast Companies, UK) used included the following: Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT), ampicillin/sulbactam (SAM), gentamicin (GEN), piperacillin/tazobactam (PTZ), imipenem (IPM), cefepime (CPM), amikacin (AK), meropenem (MEM), ceftazidime (CAZ), ciprofloxacin (CIP), tobramycin (TN), and minocycline (MN).

3.4. Carbonyl Cyanide m-Chlorophenyl Hydrazone

The (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP) test was used for phenotypic screening of active efflux pumps. The sensitivity of the bacteria studied in this research to the antibiotic IPM was evaluated by the MIC method alone and in the presence of a non-specific drug pump inhibitor called CCCP, using the micro broth dilution method with Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB). The target bacteria were evaluated as resistant to IPM. The CCCP is a substance that has an inhibitory effect on all bacteria and all efflux pumps. It does not affect gene expression and does not prevent expression, but it affects the function of pump proteins. First, MHB was prepared, and after autoclaving, it was divided into two microplate groups. The strains with at least a twofold decrease in MIC after adding the CCCP are considered strains with active efflux pumps. Real-time PCR was used to investigate the expression of genes of the AdeB efflux pump.

3.5. RNA Extraction and Real-time PCR

The total RNA content of the desired bacteria was extracted with the RNA extraction kit, Thermo, USA, according to the manufacturer’s procedure. Therefore, RNA extracted from any bacterial isolate, which is used for cDNA synthesis, must be completely free of DNA. For this purpose, DNA was removed from the RNA solution using the enzyme kit DNase I 1U/μL (a product of Fermentas company). After extracting RNA and ensuring the quality of extraction and removal of genomic DNA, cDNA synthesis was performed using the AccuPower RocketScriptTM RT PreMix kit, a product of the Bioneer company, according to the manufacturer’s procedure. After cDNA synthesis, the samples were subjected to real-time PCR to check the semi-quantitative expression of the desired efflux pumps using the primers, which are shown in Table 1 (13).

| Materials | Density | Volume Used (µL) |

|---|---|---|

| PCR master mix | 10 | |

| PCR buffer | 1x | |

| MgCl2 | 2 mM | |

| DNTPs | 0.4 mM | |

| Taq DNA polymerase | 0.2 u/μL | |

| Primers (F and R) | 0.8 μM | 0.5 |

| Template DNA | 0.5 μg/μL | 2 |

| Distilled water | - | 11 |

| Total volume | - | 25 |

Finally, the semi-quantitative expression of efflux pump gene expression was calculated using the formula 2-∆∆Ct.

3.6. Identification of Pathogenic Genes

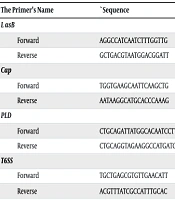

In this study, conventional PCR was used to identify the virulence genes LpsB, OmpA, Cap, PLD, and T6SS in MDR A. baumannii samples. The primers used to identify the genes are listed in Table 2. and 3.

| The Primer’s Name | `Sequence | PCR Product Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| LasB | 137 | (14) | |

| Forward | AGGCCATCAATCTTTGGTTG | ||

| Reverse | GCTGACGTAATGGACGGATT | ||

| Cap | 211 | (15) | |

| Forward | TGGTGAAGCAATTCAAGCTG | ||

| Reverse | AATAAGGCATGCACCCAAAG | ||

| PLD | 1743 | (16) | |

| Forward | CTGCAGATTATGGCACAATCCTTTCATTCCA | ||

| Reverse | CTGCAGGTAGAAGGCCATGATGTAAAAAGTT | ||

| T6SS | 142 | (17) | |

| Forward | TGCTGAGCGTGTTGAACATT | ||

| Reverse | ACGTTTATCGCCATTTGCAC |

Abbreviations: Cap, capsule; PLD, phospholipase; T6SS, type VI secretion system.

| Primer Name | Sequence Primer | Size Primer (bp) | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S | 150 | ||

| Forward | CAGCTCGTGTCGTGAGATGT | 20 | |

| Reverse | CGTAAGGGCCATGATGACTT | 20 | |

| AdeB | 84 | ||

| Forward | AACGGACGACCATCTTTGAGTATT | 24 | |

| Reverse | CAGTTGTTCCATTTCACGCATT | 22 |

The DNA of bacteria was extracted from isolates using a DNA extraction kit (Thermo, USA) following the manufacturer’s procedure. After performing the extraction steps, PCR was conducted to identify the carbapenemase genes in the studied carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria. The materials required for PCR were prepared in a 25-microliter reaction with the specified volume and concentrations for each sample and mixed in a 0.2 mL microtube (Table 1).

According to Table 1, the specific settings for the PCR were as follows for each gene: For the LpsB gene, preincubation was conducted for 3 minutes at 95°C. The cycles of PCR were performed as follows: Denaturation at 95°C for 40 seconds, primer annealing at 55°C for 40 seconds, and DNA extension at 72°C for 40 seconds per cycle. After the last cycle, the PCR tubes underwent a final extension for 7 minutes at 72°C and then were held at 4°C. It should be mentioned that this method involved 35 cycles.

The T6SS gene has the same settings as the LpsB gene, except that we used 36 cycles. The PLD and OmpA genes differ only in the annealing temperature, both of which are set at 65°C. Finally, for the Cap gene, preincubation was conducted for 3 minutes at 95°C. The cycles of PCR were performed as follows: Denaturation at 95°C for 50 seconds, primer annealing at 53°C for 50 seconds, and DNA extension at 72°C for 50 seconds per cycle. After the last cycle, the PCR tubes underwent a final extension for 7 minutes at 72°C and then were held at 4°C. This setup also involved 35 cycles.

3.7. Ethical Statement

All methods and steps, including sample collection from human subjects, were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Ethical Committee of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.MEDSAB.REC.1401.093).

3.8. Sampling Method and Sample Size

The sampling method used in this study was convenience sampling. Clinical isolates of A. baumannii were collected from various hospitals across 10 cities in Iran over one year. All non-duplicate, confirmed MDR isolates available during the study period were included. The sample size of 50 was chosen based on feasibility and comparability with previous similar studies conducted in the region, due to practical constraints such as access to clinical isolates and available laboratory resources.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software version 26. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. The association between the presence of virulence genes and antibiotic resistance patterns was statistically analyzed using Fisher's exact test (in cases of small sample size with expected values < 5) or Pearson's chi-square test (in cases of expected values ≥ 5), as appropriate for categorical data analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

A total of 50 samples were analyzed, of which 62.0% were related to males and 38.0% to females. The age of the patients from whom the samples were taken ranged from an infant to an 84-year-old man. The mean age of participants was 51.82 ± 23.62 years. All samples were collected from different cities in Iran, with 34% from Tehran, 18% from Mashhad, and the rest from Sanandaj, Esfahan, Hamedan, Tabriz, and Zahedan. The majority of the MDR isolates tested were from ICUs (61.5%), followed by fewer numbers from emergency departments (5.1%) and surgical wards (5.1%). Other specimens were from various medical-surgical units. Of the clinical isolates, the tracheobronchial tract (n = 30) and blood (n = 9) were the primary sites of recovery.

Table 4 shows the disk diffusion test results. All isolates were resistant to several antibiotics, especially β-lactams and carbapenems. The highest sensitivity was observed toward colistin and MN.

| Antibiotics | Sensitive | Intermediate | Resistant |

|---|---|---|---|

| AK | 2 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 48 (96.0) |

| GEN | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) | 46 (92.0) |

| TN | 7 (14.0) | 2 (4.0) | 41 (82.0) |

| SAM | 2 (4.0) | 4 (8.0) | 44(88.0) |

| CPM | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (100) |

| Cefotaxime | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (100) |

| CAZ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (100) |

| CIP | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 48 (96.0) |

| Colistin | 40 (80.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (20.0) |

| IPM | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (100) |

| MEM | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (100) |

| PTZ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (100) |

| MN | 14 (28.0) | 4 (8.0) | 32 (64.0) |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 2 (4.0) | 1 (2.0) | 47 (94.0) |

Abbreviations: AK, amikacin; GEN, gentamicin; TN, tobramycin; SAM, ampicillin/sulbactam; CPM, cefepime; CAZ, ceftazidime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; PTZ, piperacillin/tazobactam; MN, minocycline.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

The frequency of virulence genes among MDR isolates was as follows: The OmpA (50%), T6SS (92%), Cap (56%), LpsB (96%), and PLD (92%). The association between the presence of these genes and antibiotic resistance patterns is summarized in Table 5.

| Variables | OmpA | T6SS | Cap | LpsB | PLD | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | P-Value | Positive | Negative | P-Value | Positive | Negative | P-Value | Positive | Negative | P-Value | Positive | Negative | P-Value | |

| AK | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.07 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 24 | 24 | 44 | 4 | 26 | 22 | 47 | 1 | 44 | 4 | |||||

| GEN | 0.49 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 25 | 23 | 44 | 4 | 27 | 21 | 47 | 1 | 44 | 4 | |||||

| TN | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.11 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 4 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 21 | 22 | 40 | 3 | 22 | 21 | 41 | 2 | 40 | 3 | |||||

| SAM | 1.00 | 0.005 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 24 | 24 | 46 | 2 | 27 | 21 | 46 | 2 | 44 | 4 | |||||

| CPM | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 25 | 25 | 46 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 25 | 25 | 4 | 4 | 28 | 22 | 48 | 2 | 48 | 4 | |||||

| Cefotaxime | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 25 | 25 | 46 | 4 | 28 | 22 | 48 | 2 | 46 | 4 | |||||

| CAZ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 25 | 25 | 46 | 4 | 28 | 22 | 48 | 2 | 46 | 4 | |||||

| CIP | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 25 | 24 | 45 | 4 | 27 | 22 | 48 | 1 | 45 | 4 | |||||

| Colistin | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.17 | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 23 | 17 | 38 | 2 | 21 | 19 | 38 | 2 | 38 | 2 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 2 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 8 | 2 | |||||

| IPM | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 25 | 25 | 46 | 4 | 28 | 22 | 48 | 2 | 46 | 4 | |||||

| MEM | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 25 | 25 | 46 | 4 | 28 | 22 | 48 | 2 | 46 | 4 | |||||

| PTZ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 25 | 25 | 46 | 4 | 28 | 22 | 48 | 2 | 46 | 4 | |||||

| MN | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 10 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 13 | 1 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 15 | 21 | 33 | 3 | 19 | 17 | 35 | 1 | 33 | 3 | |||||

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 0.49 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.15 | ||||||||||

| Sensitive | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Resistant/intermediate | 25 | 23 | 45 | 3 | 27 | 21 | 46 | 2 | 45 | 3 | |||||

Abbreviations: OmpA, outer membrane protein A; T6SS, type VI secretion system; Cap, capsule; LpsB, lipopolysaccharide biotinylated; PLD, phospholipase; AK, amikacin; GEN, gentamicin; TN, tobramycin; SAM, ampicillin/sulbactam; CPM, cefepime; CAZ, ceftazidime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; PTZ, piperacillin/tazobactam; MN, minocycline.

a N/A: No statistics were computed because those variables were constant.

The active efflux pump was screened phenotypically in 13 strains (26%) according to the results of the CCCP test, and increased gene expression of the AdeB efflux pump was confirmed by real-time PCR in 6 (46%) of them. The presence of virulent genes in the samples resistant to CPM, Cefotaxime, CAZ, IPM, MEM, and PTZ was higher than in others. Additionally, the lowest frequency of virulent genes was related to resistance to MN. Fisher’s exact test, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, showed that the T6SS gene had a statistically different frequency in terms of sensitivity or resistance to SAM (P = 0.005). Similarly, the LpsB gene had a different frequency in the sensitive group to CIP versus the resistant/intermediate group to CIP (P = 0.04).

5. Discussion

This investigation identified a considerable amount of virulence genes T6SS, LpsB, and PLD in MDR A. baumannii isolates. Zeighami et al. (18) observed a high frequency of the genes OmpA and T6SS in MDR and its variants in relapsing patients in Iran. Dong et al. (19) also reported that the T6SS gene was among the frequent genes found in resistant clinical strains in China, indicating a possible role of these genes in antimicrobial resistance. Therefore, preventing A. baumannii infection by raising awareness of preventive measures, such as hand hygiene among healthcare professionals, and preventing pathogens from entering these wards via clothes or objects is highly important. We also need more detailed research on patterns of antibiotic resistance of A. baumannii in different regions of the world to understand the behavior of these pathogens and determine effective first-line and second-line antibiotic choices for use in infected patients.

A recent study in Iran found that the majority of the MDR samples were in ICUs and from the respiratory tract (18). In a recent study conducted by Elvan et al. on 67 pediatric patients infected with Acinetobacter species in Turkey, most cases were hospitalized in intensive care units; 46.3% of infections were related to urinary tract infections, 43.3% were related to bloodstream infections, and 6.7% of infections were ventilator-associated pneumonia (20).

The percentage of the frequency of OmpA, T6SS, Cap, LpsB, and PLD genes in the samples of our study was 50%, 92%, 56%, 96%, and 92%, respectively. In an Iranian study conducted by Zeighami et al., the frequency of OmpA in MDR A. baumannii samples was 81% (18). In another study performed by Dong et al. in China, it was reported that the T6SS gene was identified in 51 out of 77 A. baumannii clinical samples; also, in 8 out of 13 MDR samples and 36 out of 40 extensively drug-resistant (XDR) isolates (19). It can be concluded that the frequency of "outer membrane components" virulent genes in MDR A. baumannii is significantly high.

In the study by Wang et al. in 2024 in China, from the 255 A. baumannii samples, which were mostly found in intensive care units (49%) and from sputum specimens (80%), they found high resistance to carbapenem antibiotics. The frequency of the most found genes in their samples were blaOXA-51 (66.9%), blaOXA-23 (74.48%), AmpC (84.14%), TEM (75.86%), NDM-1 (4.83%), and KPC (8.97%) (21). In this study, the samples analyzed were 100% resistant to CPM, Cefotaxime, CAZ, IPM, MEM, and PTZ. Samples were most sensitive to colistin (80%), followed by MN (28%). In the study by Zeighami et al., the resistance rate of MDR A. baumannii samples against CIP and IPM was 100%, piperacillin was 99%, and against CPM/levofloxacin/CAZ was 97% (18). It can be concluded that IPM can be the worst choice for treating this pathogen, at least in Iran, during this timeline.

In the study by Elvan et al. in Turkey, the most antimicrobial resistance of Acinetobacter infection was related to the use of carbapenem in the previous 3 months (20). In the study by Gharaibeh et al. on the A. baumannii isolates of 150 Jordanian patients, it was reported that 90% of samples were resistant to monobactam, cephalosporins, carbapenem, penicillin, fluoroquinolones, and β-lactam antibiotics, and 20.6% of samples were resistant to colistin (22). We also confirmed in our study that our collected samples in Iran were 80% sensitive to colistin, which shows a similar pattern. However, Jeon et al. in a study in 2024 in China reported that for treating carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii pneumonia, colistin monotherapy is not a good choice, and the patients did not respond well to the treatment; therefore, monotherapy may not be recommended despite its remaining power against resistant A. baumannii infections (23).

In our study, the presence of "outer membrane components" virulent genes was mostly related to resistance to CPM, cefotaxime, CAZ, IPM, and MEM. Among the antibiotics tested, PTZ had the highest rate of resistance among MDR isolates, while MN had the lowest prevalence of resistance in this population.

This study has certain limitations. The relatively small sample size and convenience sampling method may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, clinical outcome data (e.g., patient response to treatment) were not collected, preventing correlation of resistance virulence profiles with clinical severity. Future studies with a larger sample size and multicenter designs are needed.

5.1. Conclusions

This study revealed that the virulence factors T6SS, LpsB, and PLD were highly prevalent in MDR A. baumannii isolates from clinical specimens in Iran. This suggests that virulence factors contribute to expressions of antibiotic resistance; however, additional studies, especially with susceptible isolates, will be necessary to verify this association.

5.2. Limitations

The high prevalence of T6SS, LpsB, and PLD virulence genes in MDR A. baumannii isolates highlights the possible role of these genes in antibiotic resistance. However, further genomic studies are required to investigate their potential for horizontal transmission.