1. Background

Keratomycosis, or fungal keratitis, is one of the most common infectious eye diseases. This disease, especially in cases of corneal damage, is prevalent among individuals engaged in outdoor jobs and can ultimately lead to blindness and loss of the eye (1). Tropical and subtropical regions are particularly affected by the disease, with estimates suggesting that as many as 20 to 60% of all corneal infections are due to fungal keratitis (2). Both filamentous fungi and yeasts can cause these infections. In tropical and subtropical areas, Fusarium spp. (solani) and Aspergillus spp. (flavus and fumigatus) are reported as the most common etiologies of keratomycosis, while Candida spp. species are most frequently isolated in temperate areas. Infections of the cornea with filamentous fungi have a worse prognosis than those with yeast species, and to date, almost 70 fungal species have been recognized as agents of fungal keratitis (3, 4).

Risk factors for keratomycosis include trauma to the eye (such as trauma from plant and organic materials in outdoor workers, dust), chronic superficial eye diseases, diseases that cause immune deficiency, previous use of corticosteroids, and contaminated traditional eye medications. In uncommon situations, contact lens use can also be a risk factor (Faisha Gonjiou) (5). Contact lens users, especially those in lower socio-economic demographics, are at the highest risk. This is due to a lack of education on eye hygiene care and improper use of cleaning solutions (6). Fungal keratitis is more common among men than women, and 3.5 to 4 percent of cases are found in children. Most cases of fungal keratitis occur in adults between the ages of 20 and 50 years (7).

Fungal keratitis may develop subacutely, often causing pain, blurred vision, redness, tearing or discharge, and photophobia. The disease can lead to ulceration, corneal opacity, and rarely, endophthalmitis. Fungal keratitis is five to six times more likely than bacterial keratitis to result in corneal perforation (8).

The outcome of unrecognized and inadequately treated keratomycosis could lead to corneal opacity, visual impairment, corneal perforation, and blindness (9). Direct microscopy and culture from corneal lesions still serve as the cornerstone of diagnosis for fungal keratitis. Clinical suspicion is the initial step in diagnosis; corneal scrapings or biopsy can be subjected to a direct smear and culture for documentation of the etiological agent (10). Since Sistan and Baluchestan province (southeastern Iran) is the ophthalmology center for the Southeastern Iranian population and also due to the tropical and subtropical climate of this region, the presence of dust and low hygiene levels among the people leads to a susceptibility for fungal keratitis.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of fungal keratitis using direct methods and culture of corneal scrapings of suspected patients. Moreover, in this study, the association of demographic factors of patients, such as age, gender, and habitat, with the responsible fungal species of fungal keratitis was evaluated.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sampling Method

This clinical study was a descriptive cross-sectional trial conducted over five years, from fall 2018 to fall 2023. The study population included 94 patients with eye lesions referred from ophthalmology clinics to the laboratory at Al-Zahra Hospital in Sistan and Baluchestan province (southeastern Iran). They had been diagnosed with suspected fungal keratitis based on the findings of ophthalmology specialists. Inclusion criteria were the sudden appearance of clinical symptoms, including the sensation of a foreign body in the eye, photophobia, redness, tearing, blurred vision, and loss of visual acuity. The diagnosis was determined by specialist consulting, and informed consent was obtained before sampling. Study exclusion criteria included incorrect initial diagnosis, inappropriate and inadequate sampling, and unavailability of demographic information, which excluded these individuals from the initial study.

3.2. Sampling Method

An ophthalmology specialist collected samples using a sterile lancet. One or two drops of tetracaine for local anesthesia were administered in the patient's eye before sampling. The sample from the surface lesions of the cornea was taken under sterile conditions and divided into two portions. One portion was placed in the sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) medium. The second portion was subjected to potassium hydroxide (KOH) and Gram staining for direct examination under a microscope.

3.3. Experimental Section

One to two colonies growing in the culture medium were considered diagnostically insignificant, whereas four or more similar colonies growing from a sample were considered conclusive evidence of fungal infection. Cultures were maintained for up to 3 weeks for slow-growing fungal species and reported as negative if no growth was observed. The final report was sent to the treating physician regarding samples proven by both direct and culture methods to have either a fungal infection or the presence of the fungus.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Patients' demographic, clinical, and laboratory findings were recorded in a standard questionnaire. Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 22) software. Quantitative variables were described using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation), and qualitative variables were described using descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage). Furthermore, suitable statistical tests were performed to analyze the association between variables. The threshold for statistical significance for all analyses was set at P ≤ 0.05. The questionnaire checklist included personal details (patient code, gender, age, place of residence) and laboratory results.

4. Results

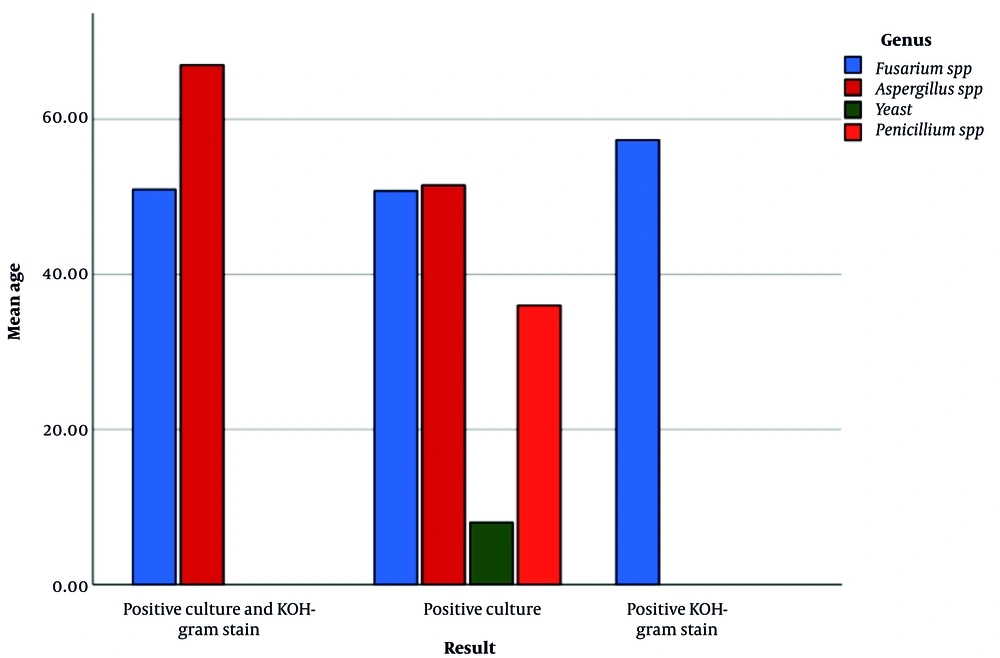

Over five years, 94 samples exhibiting indications of fungal keratitis were gathered for this investigation. The fungal species detected were Aspergillus, Penicillium, Fusarium, and yeasts. Participants with fungal keratitis ranged from 1 to 96 years old, with an average age of 53. The proportion of genders was 42.40% female and 59.57% male. Of the samples, 56 (59.57%) were from rural regions, and 38 (40.42%) were from urban areas. According to the findings of the direct and culture tests, 32 samples (34.04%) were positive solely through the culture tests, while 37 samples (39.36%) out of 94 were positive with both. Furthermore, 25 samples (26.60%) were positive for both culture and direct KOH-Gram staining at the same time. Results from direct and culture tests for several fungal species are compared in Table 1 and Figure 1. These findings suggest that the direct and cultural approaches are complementary to one another and that using both at the same time may improve the test's sensitivity and specificity.

| Genus Fungal | Diagnostic Techniques | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Culture and KOH-Gram Stain | Positive Culture | Positive KOH-Gram Stain | Total | |

| Fusarium spp. | 22 (25.3) | 28 (32.2) | 37 (42.5) | 87 (100) |

| Aspergillus spp. | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (100) |

| Yeast | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) |

| Penicillium spp. | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) |

| Total | 25 (26.6) | 32 (34.0) | 37 (39.4) | 94 (100) |

Abbreviation: KOH, potassium hydroxide.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

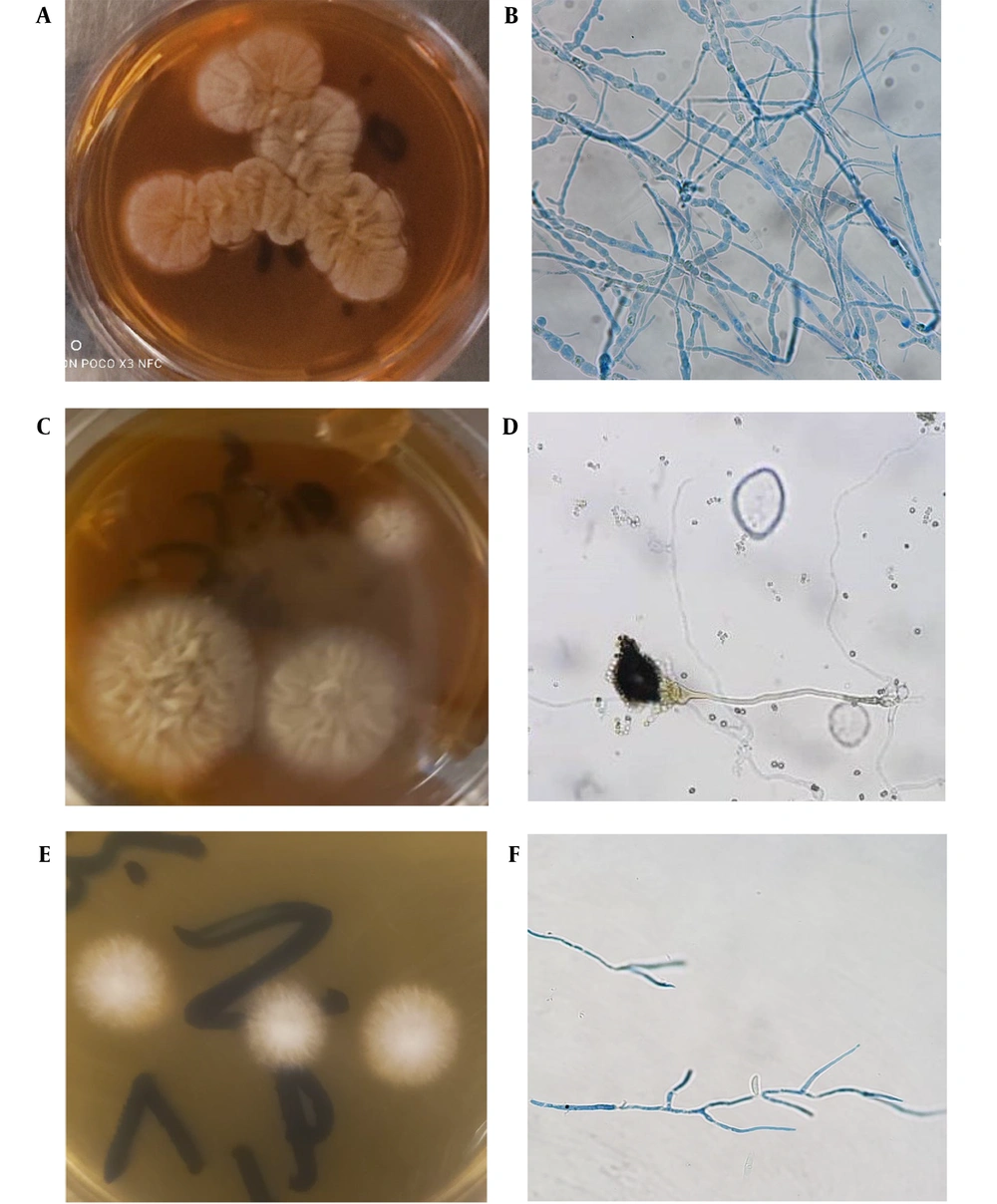

A total of 32 instances of fungal colonies developed in the culture media throughout this investigation. With a frequency of 92.6%, Fusarium spp. emerged as the most prevalent fungus species after mycological analysis (Table 1). The percentage of cases caused by Aspergillus species, Penicillium species, and yeasts was 5.3%, 1.1%, and 1.1%, respectively. The development of detected fungal colonies on SDA can be seen in Figure 2. This figure indicates the mold structure of the identified fungal species after mycological examination (the image related to Fusarium spp. in Figure 2F shows hyphae and Figure 2D shows the specific spore structure of Aspergillus spp.). Culture and direct KOH tests were negative for yeasts and Penicillium species, and only 22 cases of Fusarium species and 3 cases of Aspergillus species were reported. Comparison of sensitivity and accuracy of different diagnostic methods showed that the specificity and sensitivity of the direct test were 80% and 85%, culture were 70% and 75%, and the combination of methods were 90% and 95%, respectively.

Colony growth of fungal agents in sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) medium and direct examination of corneal scrapings with 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution and Gram staining: A, the colony of Penicillium species; B, the mycelium structure of Penicillium species; C, the colony growth of Aspergillus species; D, the spore structure of Aspergillus species; E, the colony growth of Fusarium species; and F, the microscopic structure of Fusarium species after Gram staining under a microscope with a 40x objective lens.

The prevalence of fungal keratitis agents by gender in this research reveals that Aspergillus species were the most common fungal agent in women, while Fusarium species was the most common in males. Furthermore, a more significant proportion of males than females were impacted. Additionally, the age group 31 to 50 years had the highest prevalence of the disease, whereas fewer cases of infection were reported in the age groups under 10 years and over 90 years. This may be due to the lower frequency of individuals in these age groups. Also, all four fungal keratitis agents were identified in rural residents (Fusarium, Penicillium, Aspergillus, and yeasts). However, urban residents with the infection had Fusarium and Aspergillus species, and the frequency of favorable results in rural patients was higher than in urban patients.

5. Discussion

Fusarium species was the most common agent of fungal keratitis over five years in the present study, similar to the study by Lin et al. in 2017, which found Fusarium species in 44.4% of cases and the dominant role of Fusarium is evident in studies (11, 12). In Iran, limited comprehensive studies have been conducted regarding fungal keratitis. In a study by Akbari and Sedighi, Aspergillus spp. and Fusarium spp. were reported as the most frequent pathogens responsible for keratitis in patients in central regions of Iran (6). In similar studies conducted in tropical regions, Fusarium species have been reported as the most common cause of fungal keratitis (13, 14). The dominant role of Fusarium in fungal keratitis is a finding observed in various studies worldwide. For instance, based on research conducted, Fusarium spp. has been identified as the predominant agent of fungal keratitis in countries such as India, Bangladesh, and some regions of Africa (15, 16). A study by Ranjini and Waddepally in India showed that over 70 percent of fungal keratitis cases were caused by Fusarium spp. (17). A study by Kibret and Bitew in Southeast Asia indicated that environmental factors significantly contribute to the increased prevalence of Fusarium spp., which aligns with the findings of this study. Additionally, Aspergillus species, due to their widespread distribution in various environments, can be reported as the most common cause of fungal keratitis, as observed in the study by Binnani et al. (18, 19).

Factorial epidemiological studies have shown that the diversity of fungal species responsible for fungal keratitis varies according to geographical and climatic conditions. However, it should be remembered that Fata et al. identified other significant risk factors, such as hygiene, social and economic status, occupation, history of corneal injury, frequent contact with plant leaves and branches, and use of contact lenses in women (20). The study by Karimi et al. highlighted that fungal keratitis in the border regions of Iran and Afghanistan is significantly influenced by exposure to dust and thorny and contaminated plants (21).

In the present study, based on microscopic examinations and culture results from corneal scrapings, 26.6% of patients were positive for both microscopic and culture tests, 32% were positive for culture alone, and 37% were positive for direct microscopic examination only. In this study, direct (KOH) and fungal culture tests were used as complementary methods. The results showed that combining both diagnostic methods can increase the sensitivity of the diagnosis and help confirm the diagnosis. In the study by Badawi et al., after examining 247 corneal scraping samples, they observed pure fungal culture growth in 50 cases and reported a prevalence of 24.7%. Various studies worldwide have reported different prevalences (37.5% in India, 45.1% in Ethiopia), which may indicate different inclusion criteria for individuals in the study or different disease risk factors (22, 23).

The present study shows that men (59.57%) were more affected by fungal keratitis than women. This can be explained by the higher-risk occupations of men in outdoor environments and greater exposure to environmental factors. Additionally, the highest prevalence of the disease was found in the age group of 31 to 50 years, likely due to occupational activities related to agriculture and contact with plants. Cases of infection in people aged lower than 10 and higher than 90 were less likely, both of which could be due to the fewer number of individuals in the relevant age groups. A higher proportion of fungal infections were seen in rural patients than in urban patients. This reflects the impact of poor hygiene, limited access to health facilities, and increased exposure to environmental risk factors in rural areas (24).

5.1. Conclusions

Fungal keratitis was found to affect a specific demographic, as reported by a study conducted over a period of 5 years, which isolated fungal agents in 94 samples of keratitis. The most common causative agent found was Fusarium spp., and rural patients and patients between the ages of 31 and 50 years made up the majority of those affected, attributable in part to greater exposure to environmental factors. Men were also at higher risk than women, perhaps due to higher-risk outdoor work. The application of molecular techniques for species and genotype identification of fungi related to clinical manifestations, the effect of specific environmental factors (dust and humidity), the distribution of fungal species, and propagation of intervention studies to assess the efficacy of preventive and therapeutic techniques in high-risk regions are recommendations for future research. This was one of the limitations of this study.