1. Background

Brucellosis is a well-known disease caused by the genus Brucella (1), a gram-negative, non-sporing, non-motile coccobacillus bacterium (2). It is known by several other names such as Crimean fever, Bang disease, Mediterranean fever, and Maltese fever (1). Brucellosis can be transmitted through zoonosis by coming in direct contact with infected animals, consuming contaminated animal meat and milk, or inhaling aerosols (3-5). It can also spread from human to human through the placenta, breastfeeding, sexual intercourse, blood transfusion, and bone marrow transplantation (6). The incidence of brucellosis has been reported worldwide, particularly in regions with compromised healthcare systems such as Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and some parts of the Mediterranean Basin (7). The global prevalence was estimated to be 15.53% in the year 2021 (8). This infection is endemic in the Middle East, with the highest incidence reported in Syria, Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia (9-12). Brucellosis poses a serious threat to human health (13-15) and remains a significant public health concern in Saudi Arabia, characterized by its persistence and spread despite numerous control measures. This zoonotic infection, caused by the Brucella species, has been reported across various regions within the Kingdom, underscoring the challenges posed by its transmission through both direct contact with infected animals and the consumption of contaminated animal products (16). The incidence of brucellosis in the Saudi population is estimated to be 40,100,000 people (17). Despite this, only a limited number of studies have been conducted to better understand brucellosis infection in terms of its patterns with regard to its source, clinical presentation, complications, treatment outcomes, and relapses in western Saudi Arabia. Therefore, this study is designed to address this knowledge gap and derive conclusions based on comparisons with similar studies within different regions in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to examine the demographic distribution, clinical features, primary sources of infection, diagnostic methods, and treatment strategies of brucellosis cases. This examination seeks to enhance the understanding of disease management and recurrence prevention.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

We conducted a retrospective study of 103 confirmed brucellosis cases at King Abdulaziz University Hospital (KAUH), a tertiary university hospital located in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The study included data from all patients with positive Brucella cultures or serological tests between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2022. Patient information was obtained from electronic health records and included demographics, clinical presentation, duration of symptoms, diagnostic methods, source of infection, laboratory findings, choices of antibiotics, treatment duration, and outcomes.

3.2. Specimen Collection and Processing

For the identification of isolates and antibiotic susceptibility testing, as well as serological analysis, specimens including bone marrow, whole blood, synovial fluid, and abdominal fluid were systematically collected from various hospital departments and immediately inoculated into blood culture bottles for processing.

3.3. Microbial Culturing

Consistent with the clinical microbiology laboratory protocols of KAUH, all cultures were transported to the laboratory at ambient temperature promptly to ensure the viability and accuracy of the results. The incubation process utilized the BACT/ALERT VIRTUO automated system (BioMerieux, Durham, NC, USA). Each blood culture bottle was inoculated with 10 - 15 mL of specimen. The incubation was performed under conditions of continuous agitation, and the cultures were monitored for up to 14 days or until a positive signal was detected, usually within 3 - 5 days for our samples.

Upon obtaining a positive growth indication, the contents of the culture bottles were further cultured on selective media including 5% sheep blood agar, chocolate agar, and MacConkey agar, all sourced from Saudi Prepared Media Laboratories. The MacConkey agar plates were incubated at 35 - 37°C in a standard incubator for 18 - 24 hours. The sheep blood agar and chocolate agar plates were incubated under similar temperature conditions but within an atmosphere enriched with 5 - 10% CO2 to cater to the specific growth requirements of the microorganisms. Tissue specimens underwent a parallel incubation process using the same media types, maintained at 35°C in a CO2-enriched humidified incubator.

As part of our quality control measures, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 was cultured alongside the specimens for a satellite test, ensuring the reliability of our incubation environment and culture media. All laboratory procedures, especially those involving specimen and culture manipulation, adhered strictly to biological safety level-3 (BSL-3) precautions to safeguard laboratory personnel and prevent contamination.

3.4. Microbial Isolation

Isolation of bacterial colonies was achieved through a detailed examination of colony morphology, Gram staining, and a series of biochemical tests. These tests included oxidase (0.5% tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine), catalase (3% hydrogen peroxide), urea agar (Christensen’s medium), hydrogen sulfide production, motility, and polyvalent antisera agglutination methods. Moreover, a standard tube agglutination test was employed for Brucella titration in blood samples, noting that no prezone phenomenon was encountered. The outcomes of these culture identifications were communicated directly to the attending physicians and immediately reported to the infection control department, ensuring timely and appropriate patient management and adherence to hospital infection control protocols.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present categorical variables in tables and charts. Numerical variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The relationship between categorical variables and outcomes was determined using a chi-square test. Similarly, the relationship between treatment modalities and outcomes was also assessed by the chi-square test. A one-way ANOVA test was used to establish the relationship between numerical variables and outcomes. All statistical tests were performed with SPSS version 24.0 at a confidence interval of 95%.

4. Results

Approximately two-thirds of the samples (66%) were male, and the blood culture was positive for brucellosis in the majority (91.3%) of the cases. Serology was positive in most cases (76.7%). The most prevalent source of infection was unpasteurized animal products (47.6%).

Regarding disease complications, the majority of patients (75.7%) had no complications. Among those who did, the most common was spondylitis (11.7%). Other complications included osteoarticular disease (4.9%), a common manifestation of brucellosis that causes joint pain, inflammation, and damage. It usually presents as arthritis affecting the knee, hip, and ankle, but may also involve the shoulder, wrist, elbow, or sternoclavicular joints. Neurobrucellosis was observed in 2.9% of patients, whereas endocarditis (inflammation of the heart’s inner lining) was seen in 1%. Genitourinary involvement was also noted in 1% of cases and included conditions such as epididymo-orchitis, prostatitis, nephritis, and cystitis. Moreover, 1% of cases had intra-abdominal manifestations, such as hepatic or splenic abscesses. Ocular involvement, also in 1% of patients, included uveitis (inflammation of the uvea), papilloedema (optic disc swelling), and keratitis (corneal inflammation). Pulmonary involvement (1%) manifested as bronchitis, interstitial pneumonitis, lobar pneumonia, lung nodules, pleural effusion, hilar lymphadenopathy, empyema, or abscesses. Most of the cases (79.6%) were cured, whereas 4 patients (3.9%) died and another 4 (3.9%) experienced a relapse (Table 1).

| Variables and Attributes | No. (%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.296 | |

| Female | 35 (34) | |

| Male | 68 (66) | |

| Culture | 0.575 | |

| Negative | 6 (5.8) | |

| Not done | 3 (2.9) | |

| Positive | 94 (91.3) | |

| Serology | 0.989 | |

| Negative | 2 (1.9) | |

| Not done | 22 (21.4) | |

| Positive | 79 (76.7) | |

| Source of infection | 0.267 | |

| Unpasteurized animal products | 49 (47.6) | |

| Unpasteurized camel milk/cheese | 19 (18.4) | |

| Not mentioned | 2 (21.4) | |

| Contact of skin/mucous membranes with infected animal tissue (e.g., placenta, miscarriage products) | 13 (12.6) | |

| Disease | 0.293 | |

| Absence of complications | 78 (75.7) | |

| Spondylitis | 12 (11.7) | |

| Neurobrucellosis | 3 (2.9) | |

| Osteoarticular disease | 5 (4.9) | |

| Endocarditis | 1 (1) | |

| Genitourinary involvement | 1 (1) | |

| Intra-abdominal manifestations (e.g., hepatic/splenic abscess) | 1 (1) | |

| Ocular involvement | 1 (1) | |

| Pulmonary involvement | 1 (1) | |

| Surgical treatment | - | |

| No | 93 (90.3) | |

| Yes | 10 (9.7) | |

| Outcome | - | |

| Cured | 82 (79.6) | |

| Died | 4 (3.9) | |

| Relapse | 4 (3.9) | |

| Unknown | 13 (12.6) | |

| Relapse | - | |

| Re-exposure to animals | 2 (1.9) | |

| No adherence to medication | 2 (1.9) | |

| Not applicable | 99 (96.1) |

None of the variables, such as mean age, culture turnaround time, duration of symptoms, and treatment, were statistically significantly different according to different outcomes, except for serology turnaround time (P < 0.001) (Table 2). The serology turnaround time for cases with relapse was also much higher (516.00 ± 560.029 hours) than for cases with other possible outcomes (Table 3).

| Variables | No. | Range | Mean ± SD | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 103 | 1 - 77 | 43.17 ± 20.784 | 1.655 | 0.182 |

| Culture turnaround (h) | 103 | 48 - 768 | 103.03 ± 70.848 | 0.044 | 0.988 |

| Serology turnaround (h) | 76 | 24 - 912 | 141.83 ± 109.934 | 11.459 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of symptoms (d) | 103 | 0 - 240 | 30.06 ± 39.266 | 0.415 | 0.743 |

| Duration of treatment (wk) | 103 | 0.00 - 48.00 | 9.0291 ± 8.91293 | 0.798 | 0.498 |

| Outcome | No. | Range | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cured | 61 | 24 - 459 | 135.00 ± 68.001 |

| Died | 3 | 48 - 168 | 96.00 ± 63.498 |

| Relapse | 2 | 120 - 912 | 516.00 ± 560.029 |

| Unknown | 10 | 72 - 216 | 122.40 ± 39.920 |

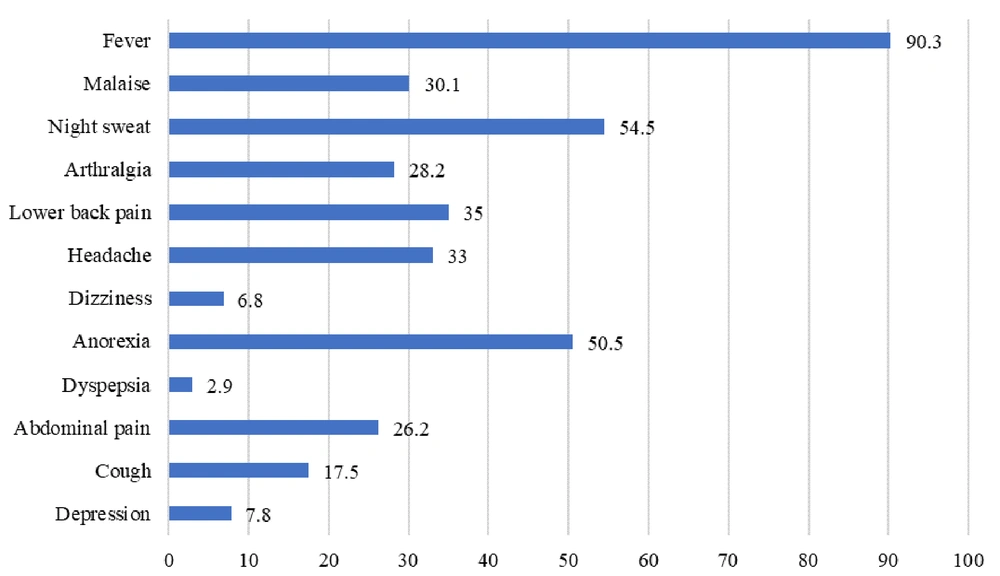

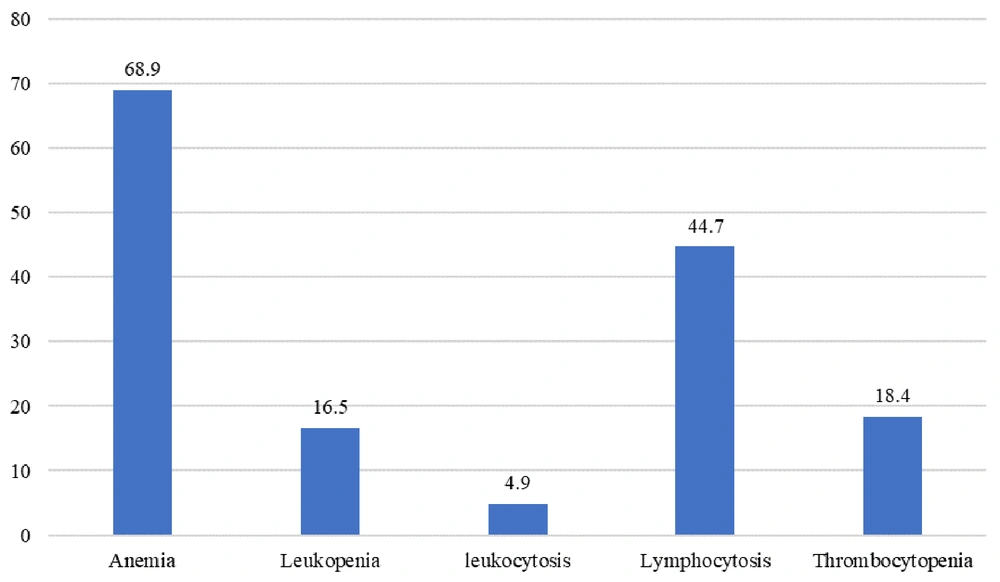

The main clinical feature of Brucella infection was fever, observed in 90.3% of cases. Night sweats and anorexia were seen in 54.4% and 50.5% of cases, respectively (Figure 1). The most frequently observed positive lab result was low hemoglobin, noted in 68.9% of cases (Figure 2).

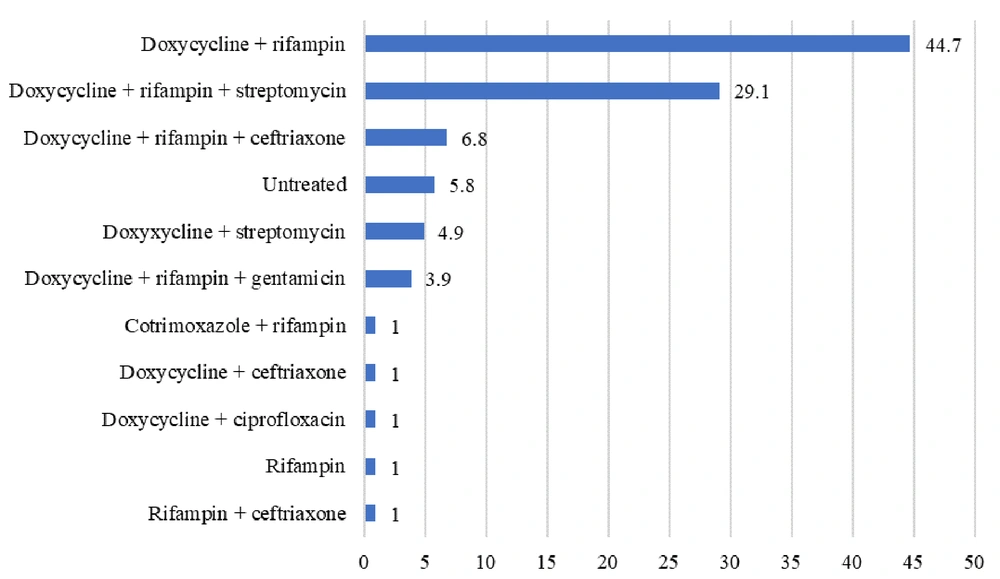

The most commonly used antibiotic combination for treating Brucella infection was doxycycline + rifampicin therapy (44.7%), while the second most common combination was doxycycline + rifampicin + streptomycin. The use of doxycycline with ciprofloxacin in 1% of cases represents a deviation from the standard brucellosis treatment regimen, which typically includes doxycycline with either rifampin or streptomycin. This combination was selected due to specific clinical considerations: Rifampicin was temporarily unavailable at the facility during treatment initiation, and the patient had a documented allergy to aminoglycosides, preventing the administration of streptomycin or gentamicin (Figure 3).

5. Discussion

This retrospective study meticulously analyzes cases of brucellosis, revealing critical insights into its epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment outcomes. Predominantly affecting males (66%), this pattern aligns with other research, indicating a higher incidence of the disease in males than in females (18-22). The mean age of the patients (44 years) corroborates demographic patterns observed in other studies, which suggest the majority of brucellosis cases occur in individuals between 15 - 44 years of age (18, 23, 24). This can be linked to higher exposure of this age group of males to infected animals either through slaughtering or herding compared to females. Higher incidence in the general population can also be related to unsatisfactory knowledge regarding brucellosis (25), as education is an important factor in raising awareness in regions where this disease is endemic (26).

In this analysis, a high positivity rate for blood cultures (91.3%) was observed, significantly exceeding the rates reported in other studies, where positivity hovered around 41% (27). This discrepancy likely stems from advanced culturing techniques and an extended incubation period employed in our laboratory, enhancing the detection of Brucella species and improving diagnostic accuracy. Unpasteurized animal products such as milk were identified as the primary source of infection, a finding consistent with other studies that highlight traditional dietary habits as a significant vector for brucellosis transmission (28-34).

Clinically, fever emerged as the most prevalent symptom, observed in 90.3% of cases, along with significant reports of night sweats and anorexia, demonstrating the systemic nature of brucellosis as documented in the literature (11, 35). The most observed lab result was anemia (68.9%), which contrasts with a similar study that reported leukopenia as the most common lab finding in patients suffering from brucellosis (36). Spondylitis was identified as a common complication, showing the need for improved clinical awareness and early diagnostic interventions for patients presenting with back pain in endemic areas. This observation aligns with findings from a tertiary hospital-based study in Saudi Arabia, which highlighted brucellosis as a leading cause of spondylodiscitis, further emphasizing the importance of considering Brucella spp. in the differential diagnosis of spinal infections (37).

The majority of cases resulted in a cure (79.6%), demonstrating the efficacy of current therapeutic approaches. However, a relapse rate of 3.9% was also observed, attributed to non-adherence to treatment regimens. This rate is comparable to other studies, which also showed the importance of adherence to treatment protocols (27). The use of doxycycline and rifampicin combination therapy was prevalent among treatment protocols, reflecting current clinical practice guidelines. Nonetheless, no statistically significant difference in treatment outcomes was observed across various antibiotic protocols. This can be linked to the fact that antibiotic regimens are also dependent on the condition of the patient (38), which necessitates further research to optimize treatment strategies for brucellosis. However, to completely eradicate brucellosis, identification of the source of infection is equally important (39), for which vaccination of animals against Brucella is commonly employed (40).

This study is not exempt from limitations. The retrospective study design makes it susceptible to documentation bias. The existing medical records used in this study could have resulted in inconsistent or incomplete data, such as adherence to treatment, follow-up information, and long-term outcomes. Moreover, this study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital where individuals from a particular demographic are treated. As such, this sample may not be representative of the entire community. Therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to primary care settings and rural areas where treatment and diagnostic options are more limited and brucellosis may have a different presentation.

Another limitation is the lack of more advanced diagnostic methods. Even though culturing and serology employed in this study followed standard protocols, molecular tools like PCR, which provide more accurate and rapid diagnosis, were not utilized. The lack of such diagnostic tools could have limited the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis, especially in culture-negative cases. Moreover, the sample size of 103 is adequate for descriptive analysis. However, it could limit the power of the statistical tests when comparing outcomes in different sub-groups or antibiotic regimens. This makes it difficult to derive accurate conclusions regarding the effectiveness of treatment protocols as well as the risk factors that could lead to relapse.

The study also did not include data such as education level and occupational exposure, which could affect the risk of brucellosis and adherence to treatment. If this information was incorporated, it could have provided a more comprehensive epidemiological analysis and informed more targeted public health interventions.

These limitations highlight the need for larger-scale, multicenter prospective studies to validate and expand upon these observations, thus enhancing the understanding of brucellosis management and control. In conclusion, this study offers valuable insights into the clinical presentation, epidemiology, and outcomes of brucellosis in a tertiary hospital setting, demonstrating the need for continued vigilance, quick diagnosis, and strict adherence to treatment protocols. Addressing the limitations identified through future research will be crucial in refining disease management strategies and mitigating the public health impact of brucellosis.