1. Background

One of the main causes of nosocomial infections, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is especially important in the evolution of many other kinds of infections, including wound infections, hospital-acquired pneumonia, bacteremia, and urinary tract infections. Because of its capacity to create biofilms, generate several virulence factors, and exhibit both innate and acquired resistance mechanisms, this gram-negative bacterium is acknowledged as a major opportunistic pathogen in clinical environments. One of the most difficult bacteria to treat is P. aeruginosa, which can readily become resistant to several medicines (1-3).

The disturbing increase of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of P. aeruginosa in clinical samples has attracted worldwide attention in past years. Traditionally, a clinical isolate of P. aeruginosa is categorized as MDR if it shows resistance to several antibiotic classes, including carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides. In these situations, good treatment choices become somewhat constrained; because of the gradual discovery of new antibiotics, specialists are usually left with older antibiotics like polymyxins. Though only two of them — polymyxin B and polymyxin E (colistin) — have therapeutic uses, polymyxins are made up of five distinct chemicals. For treating infections brought on by MDR gram-negative bacteria, colistin is regarded as a "last-resort" antibiotic (4-6).

A polycationic peptide, colistin exhibits both hydrophilic and lipophilic characteristics. These features enable colistin to efficiently interact with the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. Colistin’s cationic areas attach to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the bacterial outer membrane, displacing divalent cations such as magnesium (Mg2+) and calcium (Ca2+), which are vital structural components ensuring LPS stability. Displacement of the outer membrane structure causes the release of intracellular material and bacterial cell death. Colistin also acts like a detergent due to its amphipathic character. It solubilizes the membrane in an aqueous environment by penetrating the cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria, thereby destroying it. Colistin is a very efficient antibiotic against gram-negative bacteria since its bactericidal activity occurs even in isotonic conditions (7, 8).

Though effective, colistin use is linked to neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity; the development of colistin-resistant bacteria creates additional challenges. Regrettably, in recent years, new colistin-resistant strains of P. aeruginosa have emerged. Often the last effective choice for treating infections caused by MDR strains of P. aeruginosa, colistin makes this development a major worldwide threat. Different mechanisms can lead to colistin resistance. One such mechanism is chromosomal mutations that alter the structure of LPS, thereby restricting colistin’s access to the outer membrane. Acquiring mobile genetic components — such as mobile colistin resistance (mcr) genes — facilitates another mechanism to spread colistin resistance horizontally throughout bacterial populations. Knowing the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of colistin is crucial for guiding therapeutic decisions and preventing the misuse of this critical antibiotic (7-9).

Antibiotic-resistant diseases are becoming more of a problem in Iran, especially in the northeast where major hospitals like Hashemi Nejad Hospital are situated. These hospitals could be hotspots for the spread of MDR organisms, including P. aeruginosa, since they serve a diverse population with varying medical demands. Developing focused infection control initiatives and optimizing antimicrobial stewardship plans to combat the growing threat of MDR infections depends on understanding the local epidemiology of colistin resistance in this area. However, there is a significant knowledge gap regarding the frequency of colistin resistance among clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa in Iran.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to address this gap by assessing the susceptibility profiles of MDR P. aeruginosa isolates to colistin through their minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs).

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Collection

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from early 2022 to early 2023. The investigation began by examining the antibiogram findings of clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa collected from Hashemi Nejad Hospital in Mashhad, Iran. Isolates were included if they were collected from hospitalized patients and classified as MDR. Duplicate samples from the same patient were excluded. Selected isolates classified as MDR were moved to the research lab for further investigation. A convenience sampling strategy was used, including all MDR isolates submitted by the hospital laboratory during the study period.

3.2. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Confirmation

All isolates were subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing aimed at the species-specific ecfX gene to verify identification (10). A conventional PCR protocol was used. This molecular test guaranteed the correct identification of the bacterial species.

3.3. Confirmatory Antibiogram

A confirmatory antibiotic susceptibility test was carried out using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion technique. Among the nine antibiotics examined were piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftazidime, cefepime, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, gentamicin, amikacin, meropenem, and imipenem. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria were used to interpret the findings to verify the MDR status of the isolates (11).

3.4. Colistin Susceptibility

Colistin susceptibility was evaluated for isolates confirmed as MDR P. aeruginosa using the broth microdilution technique. Often regarded as the gold standard for calculating the MIC of colistin, this approach provides accurate information on the susceptibility profile of the isolates (6). Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used as the quality control strain. The MIC interpretation followed CLSI M100 (2025) guidelines.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the frequency of resistance. Categorical variables were summarized using percentages. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.

4. Results

Over the course of the examination, the hospital sent us 62 MDR P. aeruginosa isolates for examination. A final group of 48 isolates was included in the study after removing duplicate samples and conducting confirmatory tests, including antibiotic susceptibility testing (antibiogram) and PCR aimed at the ecfX gene.

Table 1 summarizes the outcomes of the antibiotic susceptibility tests using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion technique. The results show that all 48 isolates were 100% resistant to piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftazidime, cefepime, levofloxacin, meropenem, and imipenem, confirming their classification as both MDR and carbapenem-resistant strains. Of the isolates, gentamicin had the least degree of resistance, with 75% showing resistance.

| Antibiotic | Percentage of Resistant Isolates |

|---|---|

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 100 |

| Ceftazidime | 100 |

| Cefepime | 100 |

| Levofloxacin | 100 |

| Meropenem | 100 |

| Imipenem | 97.9 |

| Gentamicin | 75 |

| Amikacin | 97.9 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 97.9 |

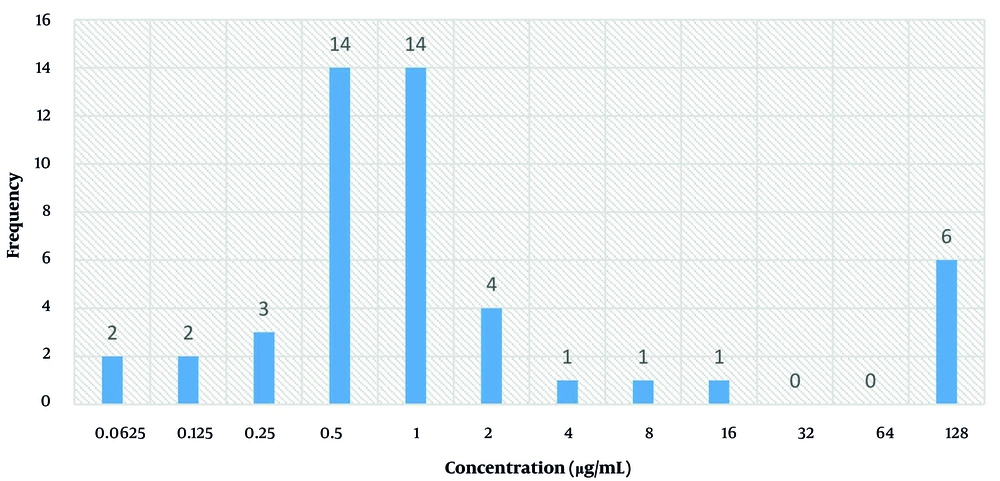

For the 48 clinical isolates, colistin’s MIC was calculated; the findings are shown in Figure 1. The MIC levels ≤ 2 µg/mL are classed as intermediate under the CLSI recommendations (M100, 2025); those with values ≥ 4 µg/mL are deemed resistant. Nine isolates (18.75% of the total MDR isolates included in the study) were found to be colistin-resistant using this definition.

5. Discussion

Particularly in clinical environments where treatment options are already constrained, the rise of colistin resistance in MDR P. aeruginosa isolates is a major challenge for global health (9, 12). Our study sought to determine the frequency of colistin resistance among MDR P. aeruginosa isolates from northeast Iran, which we found to be 18.75%. This result highlights the increasing threat of colistin resistance in this area and underscores the immediate necessity for targeted interventions.

We compared our findings with those of several studies conducted in various geographical areas to provide context. The results of the current investigation are particularly in line with those of Abd El-Baky et al., who found a significant frequency of colistin resistance (21.3%) among P. aeruginosa isolates in Egypt (13). This similarity emphasizes the common challenges faced in regions where colistin resistance is becoming a major issue. Slight disparities between our findings (18.75%) and theirs, however, might indicate differences in regional antibiotic use patterns, infection control policies, or the genetic diversity of circulating P. aeruginosa strains. Abd El-Baky et al. (13) also found mcr genes such as mcr-1 in certain colistin-resistant isolates; our study, however, did not examine these genetic elements. This difference emphasizes the importance of future studies investigating the underlying causes of colistin resistance in our area. Moreover, our results should be placed in context within the larger systematic study done by Narimisa et al., which projected the worldwide incidence of colistin resistance to be about 1%, with regional differences including a much higher rate of 4% in Africa (4). Although our research shows a significantly greater resistance rate (18.75%), this difference can be attributed to variations in geographic focus, sample size, and the specific inclusion of MDR isolates in our investigation.

Furthermore, Narimisa et al. (4) underlined the importance of chromosomal mutations and efflux pump overexpression in colistin resistance, mechanisms not investigated in our work but deserving more research because of their possible influence on resistance patterns in northeast Iran. Several regional studies in Iran have reported varying rates of colistin resistance in P. aeruginosa isolates. For instance, Jafari-Ramedani et al. (2024) reported a resistance rate of 9% in Ardabil, while Tahmasebi et al. found a lower rate of 3.96% using the E-test method. Our study, which focused exclusively on MDR isolates from a tertiary care referral hospital, may inherently reflect a higher baseline of antimicrobial resistance (5, 14).

The higher resistance rate in our study may be partly attributed to the presence of biofilm-producing isolates in the sample and differences in patient populations or stewardship practices. Jafari-Ramedani et al. also identified specific pathways contributing to colistin resistance not covered in our work, including amino acid changes in the PmrB protein and oprD gene down-regulation. These findings highlight the multifactorial nature of colistin resistance and support the need for localized surveillance and further research into underlying mechanisms (5).

Our results also relate to those of Tahmasebi et al., who used the E-test method to assess colistin resistance among β-lactamase-producing P. aeruginosa isolates. Among 101 isolates, their study found a lower colistin resistance rate of 3.96%, which fits the lower end of the range seen in earlier research. Tahmasebi et al. emphasized the vital role the mcr-1 gene plays in the dissemination of KPC-producing ESBL and P. aeruginosa strains, a mechanism not investigated in our work. Their discovery of new sequence types — ST217, ST1078, and ST3340 — in colistin-resistant isolates also underscores the genetic variation of resistant strains and the importance of molecular typing in understanding the distribution of colistin resistance (14).

The results of this study have significant therapeutic implications as they highlight the urgent need for improved antibiotic control and infection management policies in hospital environments. The significant frequency of colistin resistance among MDR P. aeruginosa isolates suggests a potential inadequacy of relying solely on colistin as a last-resort antibiotic, emphasizing the necessity for alternative treatment options.

Our research, however, has certain limitations. First, due to limited funding, we did not evaluate key gene changes in all colistin-resistant isolates. Second, we did not investigate all mcr gene variants (mcr-2 to mcr-9), which could have helped clarify the resistance mechanisms. Future research should address these gaps to provide a more comprehensive overview of colistin resistance in this area.

5.1. Conclusions

This study revealed an 18.75% rate of colistin resistance among MDR P. aeruginosa isolates in northeast Iran. These findings emphasize the urgent need for ongoing antimicrobial surveillance and stewardship, especially in tertiary care centers.

5.2. Limitations

This study was conducted in a single referral hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Molecular mechanisms of resistance, including mcr genes and chromosomal mutations, were not assessed due to resource limitations. Additionally, patient-level clinical data were not analyzed, which could have provided further insight.