1. Background

Due to increasing amounts of micropollutants, in the twenty-first century, the infrastructure for water treatment is insufficient. Wastewater is contaminated with a range of pollutants, such as surfactants, endocrine disruptors, and products from pharmaceuticals and personal care (1). Once antibiotics are introduced into ecosystems, they can alter the assessment of microbial community structure, thereby affecting the ecological function of aquatic environments (2). Typically, around 30 - 90% of administered doses of water-soluble antibiotics are excreted in animal urine and feces. In addition to half of used antibiotics, a large amount of antibiotics also discharged in wastewater has been taken from disposal of these unused drugs (2). Active compounds from these antibiotic residues and other pharmaceutical agents exert selective pressure and are discharged into the municipal wastewater system on a large scale before reaching the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) (3). The primary concern regarding the release of antibiotics into the environment is the emergence and dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and resistant bacteria (ARB), which could diminish the effectiveness of treatments against pathogens in both humans and animals (4). One common mechanism for acquiring resistance is through spontaneous mutations in bacterial DNA occurring at a much higher rate than lethal antibiotic concentrations of antibiotics would suggest (5). Furthermore, several of the pathogenic bacteria present in sewage also harbor ARGs that can be integrated into mobile genetic elements to allow horizontal gene transfer to indigenous environmental bacteria (6). A significant portion of ARB and ARG are released into wastewater via fecal waste from livestock. Research by Bonten et al. (7) reported that 80.5% of stool samples from healthy subjects harbored ARB and that 98% of them were Escherichia coli after cultivation. When effluents are discharged, these bacteria may multiply in the environment. Emergence and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and ARB is considered one of the top three threats, which is driven by the increased use of antibiotics (8). Pathogenic bacteria and fecal indicator microorganisms have received recent attention in research, especially in strains of Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter spp., Aeromonas spp., and E. coli in wastewater that frequently harbor ARGs (2). In aquatic environments, a total of 38 common genes have been identified, including qnrS associated with fluoroquinolone resistance (9). The region investigated in this study was Hamedan in western Iran. The presence of antibiotics in livestock wastewater contributes to the development of resistance among commensal and environmental bacteria, which can diminish the effectiveness of these drugs in treating both humans and animals. Despite the significance of antibiotic resistance and pathogens in livestock wastewater, there is limited understanding of how they transfer to agricultural fields. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics were chosen for this analysis due to their widespread use in livestock production and their relevance to public health. The aim of this study was to measure the levels of antibiotic resistance and pathogen contamination in wastewater released from livestock farms to agricultural areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

The location of the study, Hamedan, is typical of the geographical regions spanning the Alvand Massif in northwestern Iran, a geomorphic unit of intrusive-glacial origin. The total area of agricultural land is about 950 thousand hectares, of which 630 thousand hectares are used for dry farming. Only six percent of the province's area is without vegetation. According to the 2016 census, the city was home to 554406 residents (174731 households). Hamedan has a growing peri-urban area near the urban markets, although the socio-economic conditions are generally low. As in the rest of Iran, small-scale cow farms are built next to the houses in Hamedan, with modest cow sheds for a small number of cows (usually less than 50 cows). In total, there are 66 dairy farms with an estimated livestock of 19207 animals spread across nine sub-areas in Hamedan province. The milk and meat production associated with livestock farming is 540 tons daily and 29000 tons annually in the region, respectively (10).

2.2. Study Design and Scope

This cross-sectional study took place during a clearly defined seven-month period from June 1 to December 31, 2023, and involved a quantitative survey of households as well as the analysis of wastewater samples for biological and antibiotic resistance. Additionally, the research focused on cow farms in the Hamedan region and its surrounding agricultural areas. The study analyzed wastewater runoff from cow sheds, households, and agricultural fields.

2.3. Study Population and Farm Characteristics

The 24 participating farms were characterized in detail to understand potential confounders affecting antibiotic resistance patterns. The average herd size was 42 ± 15 cows (range: 18 - 65), with an average milk production of 18.5 ± 4.2 liters per cow daily. All farms maintained Holstein-Friesian cattle breeds, and the average farm operation duration was 14 ± 8 years. Key management practices were documented: Eighteen farms (75%) used commercial feed supplements, while 6 farms (25%) relied primarily on pasture grazing. Regarding veterinary care, 15 farms (62.5%) had regular veterinary supervision, while 9 farms (37.5%) consulted veterinarians only during emergencies. Antibiotic usage patterns revealed that 20 farms (83.3%) reported using antibiotics for both therapeutic and prophylactic purposes, while 4 farms (16.7%) claimed to use antibiotics only for treating sick animals.

2.4. Potential Confounders and Control Measures

Several potential confounders were identified and documented, including farm management practices, antibiotic usage history, and environmental factors.

2.5. Sample Collection

After conducting a survey of 100 households between June and August 2023, a selection of 24 cow farms was made for sampling, taking into account their locations in different villages and the wastewater they release into those areas, including residential zones and agricultural lands. The chosen farms were also identified based on their interconnections, drainage regions, and proximity to agricultural fields in Hamedan. Four sampling points were identified from each selected farm to obtain a total of 96 wastewater samples, which were collected monthly from September to December 2023.

2.6. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The farms were included in the sampling frame on the basis of the following criteria: Exclusively active dairy farms, farms had to have an active and accessible wastewater discharge point (e.g., pond, drainage canal) releasing wastewater into the environment, farms were selected to ensure representativeness across different villages and drainage regions within the study area of Hamedan, farms whose wastewater discharge was in close proximity to residential areas or agricultural land were favored. Individual wastewater samples were included in the analysis if they: Had a minimum volume of 1 liter, were collected within the designated study period (between June and December 2023), were brought to the laboratory on ice, and were processed within the prescribed time window of 24 hours after collection. Samples were excluded from analysis for the following reasons: Any sample that was not kept at 2 - 8°C during transport or that had exceeded the 24-hour time limit for processing was discarded. The sampling procedures for wastewater were in accordance with Iranian standard No. 7960 for water and wastewater sampling (11). Approximately 1 liter of wastewater was collected using disinfected stainless steel dippers. The water samples were collected from ponds or canals at a depth of about 20 cm below the surface in polypropylene bottles with an air space of 2.5 cm in each bottle and transported to the laboratory on ice for processing within a maximum of 24 hours after collection. The bottles were labelled with the type of sample, a code, and the location. These samples were analyzed for E. coli. All samples were kept in a cooler (2 - 8˚C) for transport to the laboratory and were tested on the same day.

2.7. Bacteriology Analysis

The microbiological analysis was carried out by the Laboratory for Microbiology. Eosin methylene blue agar was utilized to isolate E. coli from wastewater samples. Prior to this, the agar plate surfaces were dried, after which 0.1 mL of the sample was pipetted onto each plate and evenly spread using a sterile spatula. The plates were then incubated for 24 hours at 37˚C. The appearance of green, metallic colonies on the agar indicated the presence of E. coli. The isolation process followed the method outlined by Pham-Duc et al. (12).

2.8. Antimicrobial Resistance and Susceptibility

Testing The Kirby-Bauer diffusion susceptibility method (13) was employed to assess the antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance patterns of the isolated E. coli strains. This process involved subculturing the bacteria on Muller-Hinton (MH) agar (Himedia, India). Standard antimicrobial diffusion discs with a depth of about 4 mm were placed on the agar surface and incubated at 37˚C for 18 - 24 h. Escherichia coli strains were tested against 16 antibiotics, including: Nalidixic acid (NA; 30), doxycycline (DO; 30), ceftazidime-avibactam (CAZ-AVI; 10/4), ciprofloxacin (CIP; 5), cefepime (CPM; 30), imipenem (IPM; 10), cefotaxime (CTX; 30), ceftriaxone (CRO; 30), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT; 25), amoxicillin (AMX; 30), amikacin (AK; 30), gentamicin (CN; 30), cefoxitin (FOX; 30), aztreonam (ATM; 30), and piperacillin (PRL; 30). The diameter of the zone where growth was inhibited was measured with calipers, and the results were assessed using the CLST M 100 ED 28-2018 method (14).

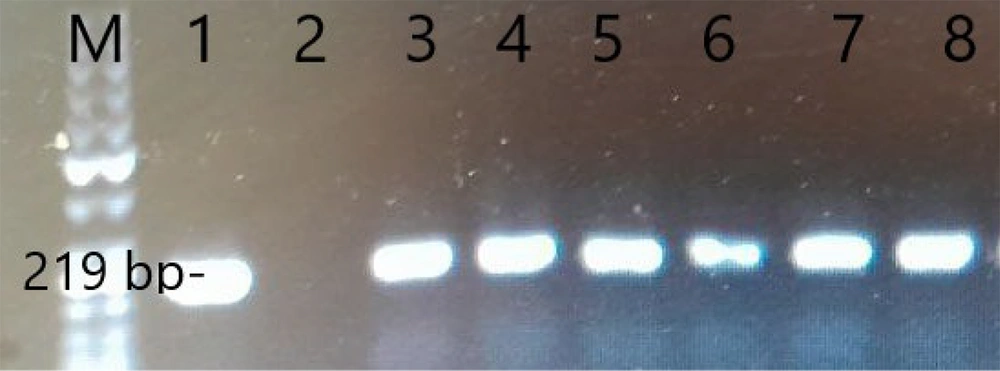

2.9. Isolation of Bacterial DNA (Escherichia coli) in Wastewater

Bacterial DNA isolation was carried out using the boiling method (15), and the quality and quantity of the extracted DNA from bacterial cultures was assessed using UV spectroscopy. To evaluate DNA purity, we measured the optical density (OD) at 260/280 with a Scan-Drop-Volume spectrophotometer (Implen, Germany). For polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, we only included samples with a DNA purity close to 1.8, as values below this threshold suggested sample contamination. DNA amplification was conducted in PCR on a thermos-cycler (Bio Rad, USA), for 35 cycles, using a master mix (Kimia Danesh Tajhiz, Iran) and specific primers for the qnrS gene. The working protocol uses a 20 µL reaction volume by adding 12.5 µL PCR mix and 1 µL primer as well as 3 µL DNA sample. The sequence of the primers used and the fragment size are listed in Table 1.

| Gene, Primers | Oligonucleotid Sequence (5´ → 3´) | Size |

|---|---|---|

| qnrS | 219 | |

| Forward | TCACCTTCACCGCTTGCACATT | |

| Reverse | AATCACACGCACGGAACTCTATACC |

3. Results

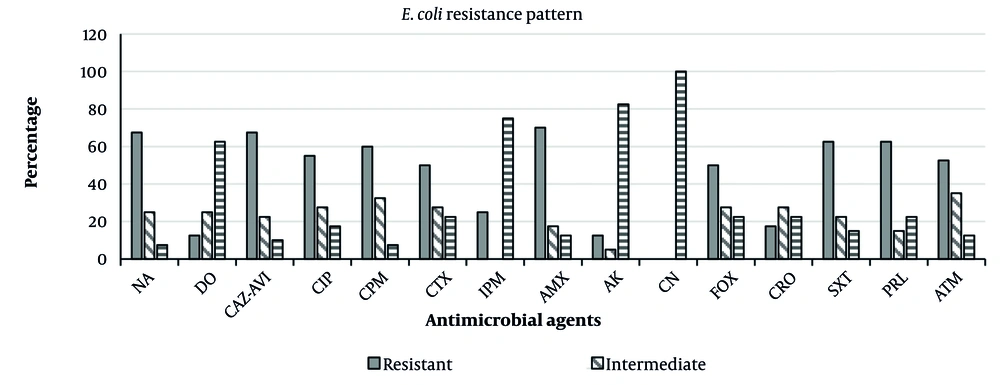

In water samples taken from various locations in Hamedan, 40 E. coli isolates were detected. Of the 40 isolates tested, 6 (15%) were positive for the qnrS gene (Figure 1). The sensitivity was tested to different antibiotics according to CLSI guidelines, which showed the highest resistance rate for AMX (70%). The frequency of resistance detected in E. coli strains for the antibiotics tested is shown below: Nalidixic acid (67.5%), DO (12.5%), CAZ-AVI (67.5%), CIP (55%), CPM (60%), IPM (25%), CTX (50%), CRO (17.5%), SXT (62.5%), AMX (70%), AK (12.5%), CN (0), FOX (50%), ATM (52.5%), and PRL (62.5%). Figure 2 represents the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of isolates obtained from Hamedan wastewater.

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Escherichia coli isolated from livestock wastewater in Hamedan, Iran. Nalidixic acid (NA), doxycycline (DO), ceftazidime-avibactam (CAZ-AVI), ciprofloxacin (CIP), cefepime (CPM), imipenem (IPM), cefotaxime (CTX), ceftriaxone (CRO), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (SXT), amoxicillin (AMX), amikacin (AK), gentamicin (CN), cefoxitin (FOX), aztreonam (ATM), and piperacillin (PRL)

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated high levels of E. coli in wastewater applied to farmland from small-scale dairy farms. The contamination in the community and agricultural fields was partly due to household wastewater. This study's findings indicate that fluoroquinolone-resistant genes are found in isolated E. coli. Overall, the E. coli isolates from Hamedan demonstrated antibiotic resistance in the following order: Amoxicillin, NA, ceftazidime, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. In the multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains, the key antibiotics with high resistance rates were similar, but ranked differently. Multidrug-resistant strains were more resistant to most classes of the antibiotics. Recent research has underscored the significant levels of antibiotic resistance among E. coli strains, highlighting the urgent issue of antibiotic resistance in Hamedan. Escherichia coli are significant opportunistic pathogens responsible for urinary tract infections in both animals and humans (16). The misuse of these antibiotics has led to selective pressure in the development of multi-drug resistant bacteria. The introduction of quinolones into therapy in the 1960s was a real advance for medicine at the time. Regrettably, after just ten years of use, the initial instances of resistance emerged, although their frequency was significantly lower than it is now (17). In the present work, we found that E. coli recovered from livestock wastewater had relatively high rates of quinolone resistance (67.5%). Livestock wastewater is an important source of quinolone resistance in Hamedan, Iran. The relatively high quinolone resistance rates found in the present study could be due to the misuse of these antibiotics. Based on the results of the present study, the highest resistance rate was found for NA (67.5%). This finding was higher than previous reports from Hamedan, Iran (18). Due to the increasing incidence of MDR, fluoroquinolones are currently considered the first choice for the treatment of calf diarrhea. In fact, several studies have documented the emergence and spread of fluoroquinolone-resistant enteric disease. The growth of this phenomenon over time might align with the significant identification of qnr genes. This has been a hypothesis among several researchers because of the strong connection between qnr genes and various forms of resistance (19). This result aligns with earlier research (20, 21), including an Italian survey in which 54% of the veterinarians surveyed identified fluoroquinolones as their top choice and 38% as their second choice for treating diarrhea in calves (22). Additionally, a study conducted in Switzerland found fluoroquinolones were the most frequently used treatment for 47% of parental treatments (23). A straightforward comparison of the values found in wastewater in Hamedan with those from clinical units in other parts of the world revealed a 29.2% reduction in qnr gene incidence in Iran, particularly in Tehran (24), while the Netherlands showed a significant 78% decrease in genes encoding qnrA (25). Like other developing countries, Iranian farmers frequently purchase medications for their animals directly, as veterinary medicines are readily accessible in various locations throughout the province (26). For a long time, antibiotics have been commonly used by livestock breeders in Iran as growth enhancers. Furthermore, many customers tend to implement some treatment methods on their own before seeking assistance at a veterinary diagnostic and medical facility. They have begun using various antibiotics or have discontinued their treatment prematurely. Furthermore, antibiogram testing is a relatively new concept that has not been widely embraced by many customers. Few farmers see this test as essential or prioritize it, believing it is not required and thus feel no obligation to conduct it. Additionally, veterinarians or clinicians who prescribe more medications for animal treatment tend to be more favored. Many clients are unwilling to incur any costs beyond the consultation fee, including laboratory expenses. Besides the factors mentioned earlier, veterinarians can also contribute to the rise of AMR. This illustrates how their traits influence their choices regarding the development of AMR. Many newly graduated veterinarians lack experience in prescribing medications, contributing significantly to the rise of AMR. Additionally, many of these veterinarians often diagnose diseases and prescribe treatments primarily based on their personal experiences. Antibiogram testing, a newer therapeutic approach, has not been widely embraced by the veterinary community. Furthermore, many people in society are not well informed about AMR and its implications for veterinary practice. For some veterinarians, AMR is not considered a critical factor in diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. This study has several limitations. Firstly, the non-random sampling method used may not accurately represent specific cow management practices or water management strategies. Secondly, the research focused solely on the resistance gene for fluoroquinolones and did not examine AMR genes for other antibiotics. Additionally, the samples were collected over a brief period, from June to December 2023, without significant seasonal variation. More research is needed to determine how seasonal factors might influence levels of antibiotic resistance and pathogen load in wastewater. Nonetheless, the findings offer insights into the prevalence of E. coli and antibiotic resistance in wastewater at a particular moment in time. A multifaceted approach that considers the impact of co-selective elements like biocides and heavy metals, along with resistance genes, could facilitate a thorough exploration of these factors in the realm of AMR.

4.2. Conclusions

The findings of this study reveal that the wastewater in Hamedan is tainted with antibiotic-resistant E. coli, which poses a significant risk to agricultural communities located downstream. This contamination not only threatens public health by fostering antibiotic resistance among microbial populations but also underscores the need for improved wastewater treatment to lower bacterial levels to safe standards before it is utilized in aquaculture and agriculture. Effective wastewater management strategies, such as composting and biogas systems, should be prioritized to address this issue.