1. Background

The human body is constantly exposed to numerous pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and other microorganisms, which can lead to infectious diseases. Establishing an infection typically involves a pathogen making contact with the host, colonizing epithelial surfaces of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, or urogenital tracts, and then overcoming the innate immune defenses of the epithelia and underlying tissues. If successful, this initial breach often triggers an adaptive immune response that develops over several days and usually leads to the clearance of the infection. Infectious diseases are, therefore, disorders caused by these invading organisms (1).

One recent example of a widespread infectious disease that has caused significant mortality and imposed considerable physical, psychological, and economic burdens is COVID-19. This disease is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which primarily enters host cells by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and utilizing cellular serine protease transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2). While ACE2 is expressed in various cell types, including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells, and found in organs such as the heart, brain, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and liver, the lungs are the major site of SARS-CoV-2 infection. A notable proportion of individuals who survive the acute phase of COVID-19 may experience lasting health issues and persistent multi-organ injuries (2).

The concept of post-infectious disease syndrome refers to complications that arise after the acute phase of an infectious illness and can significantly impact the physical health, psychological well-being, and quality of life of survivors over an extended period. Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) define "Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" as symptoms that persist between 4 and 12 weeks after the initial onset of the disease, and "post-COVID-19 syndrome" or "Long COVID" as symptoms that continue beyond 12 weeks. Post-COVID-19 fatigue is a primary and highly prevalent sequela of COVID-19 (3). It is often associated with difficulties in performing daily tasks, self-care, and mobility, as well as impairments in social and recreational activities and challenges returning to work. Although the majority of COVID-19 patients survive the acute infection, COVID-19 is not merely a short-term illness. Survivors face the risk of long-term sequelae affecting multiple systems, including respiratory, neuropsychiatric, cardiovascular, hematologic, gastrointestinal, renal, and endocrine manifestations. Furthermore, patients hospitalized with COVID-19 frequently report symptoms such as fatigue, breathlessness, muscle weakness, and psychological distress following hospital discharge (4).

Given that sequelae of infectious diseases can impact survivors for many years, comprehensive medical services are essential. These services often extend beyond pharmacological treatment to include nutritional support, psychological health interventions, and exercise rehabilitation. As a multi-system disease, COVID-19 often necessitates comprehensive rehabilitation to facilitate recovery in affected individuals. The NICE recommends that progressive rehabilitation programs are ideally initiated within the first 30 days (the post-acute phase) to maximize their impact on recovery (5). Drawing from the documented benefits of exercise rehabilitation in patients with infectious diseases, particularly viral illnesses similar to those caused by SARS-CoV-2, it is plausible that rehabilitation programs can effectively reduce symptoms such as dyspnea and drug complications, alleviate anxiety, minimize disability, preserve function, and improve the quality of life in COVID-19 patients.

2. Objectives

This article aims to investigate the effects of a selected-exercise-rehabilitation (SER) program on certain physiological, psychological, and physical indicators related to post-COVID-19 fatigue. Furthermore, it explores the possible underlying causes of fatigue in COVID-19 patients and how SER might address them. This article will demonstrate the impact of selected exercise rehabilitation in this context.

3. Methods

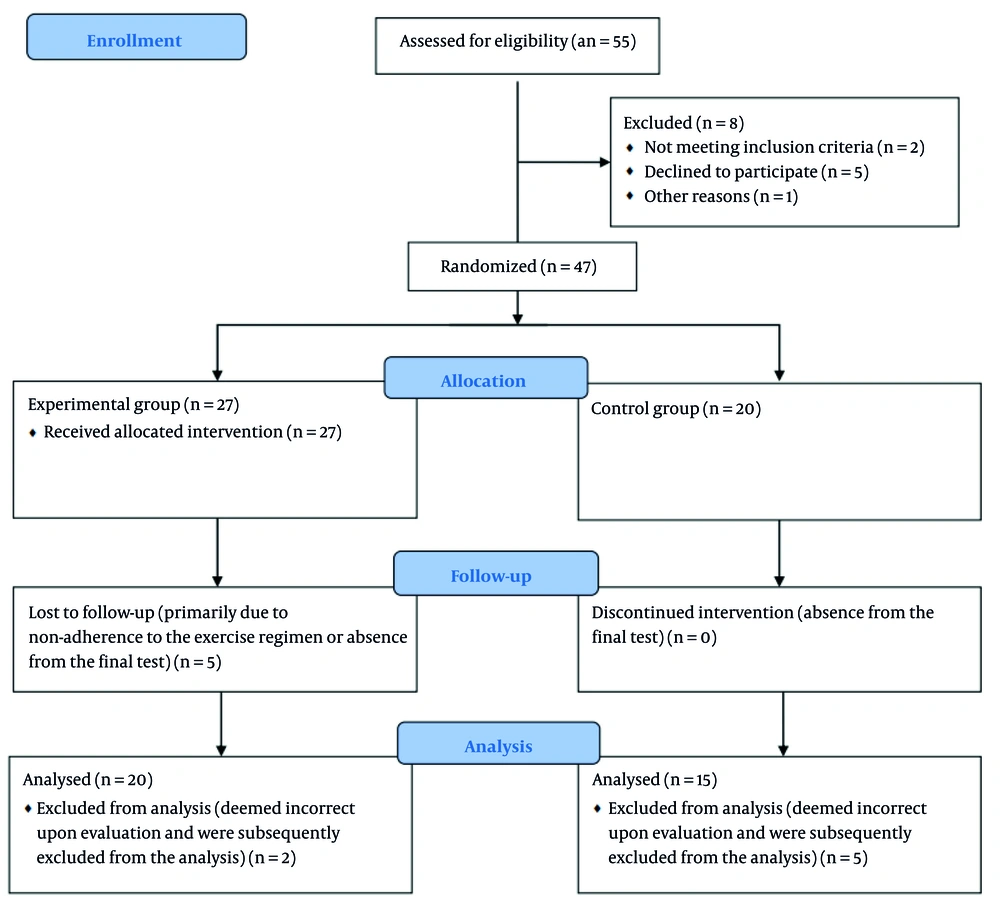

This experimental study was conducted at the COVID-19 center of Al-Zahra Hospital in Isfahan, Iran, over a period of six months, from February to July 2022. During the first four months of the study, 55 eligible patients were approached for potential inclusion in the study. Inclusion criteria of this study were hospitalized COVID-19 patients with a definitive diagnosis based on PCR tests or clinical and radiological evidence. Patients also needed to be diagnosed with respiratory complications of COVID-19 by a pulmonologist. The mean age of the included patients was 46 ± 5 years. Of these, 47 patients were accepted to participate and randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n = 27) or the control group (n = 20).

The control group adhered to a distinct protocol, foregoing the prescribed head exercises. Their participation was limited to the pre-test and post-test assessments to provide a baseline for comparison against the intervention group. Regarding underlying diseases, only physical conditions that precluded participation in rehabilitation activities were considered as exclusion criteria; other underlying diseases were not considered for exclusion. The criterion for initiating the SER program and performing baseline (pre-test) measurements was the patient having passed the acute phase of the disease, which was approximately two to three days before hospital discharge.

Participants were withdrawn from the study based on several predefined criteria to ensure patient safety and data integrity. These criteria included patient dissatisfaction with their continued participation, absences exceeding three training sessions, or non-participation in the post-test assessment. Furthermore, any alteration in a patient's clinical status that led the consulting pulmonologist and infectious disease specialist to recommend exercise discontinuation also resulted in withdrawal from the intervention. According to the CONSORT flow diagram for attrition/recruitment in Figure 1, some patients had relapses during the eight weeks of the exercise program and subsequent post-test measurements, primarily due to non-adherence to the exercise regimen or absence from the final test. Additionally, data were deemed incorrect upon evaluation and were subsequently excluded from the analysis.

Ultimately, data from 35 patients were included in the statistical analysis, encompassing both the control and experimental groups. The study population consisted of 57% men and 43% women. All participants who completed the study were analyzed according to their original group assignment, irrespective of group changes during the study period. Inclusion criteria were hospitalized COVID-19 patients with a definitive diagnosis based on PCR tests or clinical and radiological evidence. Patients also needed to be diagnosed with respiratory complications of COVID-19 by a pulmonologist. The mean age of the included patients was 46 ± 5 years.

Regarding underlying diseases, only physical conditions that precluded participation in rehabilitation activities were considered as exclusion criteria; other underlying diseases were not considered for exclusion. The criterion for initiating the SER program and performing baseline (pre-test) measurements was the patient having passed the acute phase of the disease, which was approximately two to three days before hospital discharge.

The following outcome measures were assessed: Blood C-reactive protein (CRP) and white blood cell (WBC) count were tested at the laboratory of Al-Zahra Hospital. The 6-minute walk test, Borg rating of perceived exertion (RPE, for breathlessness), and Beck Depression Inventory scales were measured within the hospital setting. Forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC), and their ratio (FEV1/FVC), were examined at the respiratory clinic of Al-Zahra Hospital. The experimental group participated in the SER program, while the control group received standard care without the structured exercise program for eight weeks.

This study employed an assessor-blinded design, as the medical staff from the hospital and clinic who conducted the pre- and post-test evaluations were unaware of the participants' group assignments. Additionally, the study was partially single-blinded because the control group was blinded to the specific activities of the experimental group; efforts were made to mask the comparative nature of the study and the specific intervention being tested from the perspective of the control group participants.

The SER program was designed based on rehabilitation articles with the keywords severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), COVID-19 and rehabilitation (6, 7), pulmonary rehabilitation techniques for patients with head injuries and COVID-19 patients used in rehabilitation clinics (8, 9), strength training for sedentary individuals and resistance training with equipment and body weight (10, 11), flexibility and balance exercises originating from yoga and Pilates (12, 13), and aerobic exercises (14, 15). The program was developed under the supervision of exercise physiologists and infectious and pulmonary specialists.

Exercise variables, including intensity, duration, volume, and frequency, were personalized based on each patient's needs, abilities, and available equipment. Each week, the exercises were generally designed at a low to moderate intensity, assessed using the Borg RPE after each session. The frequency of exercises ranged from three to five days per week. The duration of each exercise session was gradually increased from fifteen to sixty minutes over the program duration. Exercise sessions were performed under the supervision of an exercise physiologist.

For the first three weeks of the SER program, exercises were conducted remotely using social communication tools due to the possibility of virus transmission. Exercise intensity during this period was guided by the individual's self-perception of exertion using the Borg RPE Scale and the trainer's assessment of the patient's changing ability to perform movements. From the fourth to the eighth week, in-person exercise sessions were introduced. During these sessions, both the Borg Scale and heart rate were measured to monitor exercise intensity.

Due to the transmissible and dangerous nature of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, training sessions in the first four weeks were conducted remotely using video calls on social networks and recorded videos. In the final four weeks, the training sessions were held in person at a medical and rehabilitation center under the supervision of a trainer and a doctor. A brief overview of the program is given in Table 1.

| Weeks of Training | Overview of Exercises |

|---|---|

| First week (5 to 4 days a week for 20 min) | Exercises focused on correct breathing, walking at home Standing, and sitting on a chair stretching exercises |

| Second week (5 to 4 days a week for 30 min) | Breathing exercises and stretching exercises by increasing the intensity |

| Third week (5 to 4 days a week for 30 min) | Breathing and stretching exercises with external pressure; Performing strength exercises without external weights |

| Fourth week (3 to 4 days a week for 30 min) | Warm-up exercises are in the main body of strength training exercises, which are lightweight and cool down more in a sitting position. |

| Fifth week (3 to 4 days a week for 40 min) | Warm-up steps including stretching and basic movements are the main body of the exercise including basic aerobic movements in addition to strength and cooling down. |

| Sixth week (3 to 4 days a week for 40 min) | Increasing the intensity of the exercise by increasing the weight, doing more standing without assistance, and adding balance exercises to the program |

4. Results

To examine the effect of the SER program on the different outcome variables, repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. Prior to the ANOVA, the assumptions of normality (assessed using Shapiro-Wilk tests) and homogeneity of variances were evaluated and found to be non-significant for all variables, indicating that the assumptions were met. Post-hoc analyses (Tukey and LSD) were performed to further explore significant main effects and interactions identified by the omnibus ANOVA test. A significance level of α = 0.05 was used, with 95% confidence intervals reported.

Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's d to quantify the magnitude of observed differences. Within-group comparisons (pre-test to post-test) for both the experimental and control groups consistently yielded Cohen's d values ranging from 0.63 to 1.93. This range represents large effect sizes to approaching a medium magnitude. Also, descriptive statistics of each factor’s data as the total mean in both the control and experimental groups in pre-test and post-tests show the effective change in variables (Table 2).

| Variables | Total | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | ||

| Chalder Fatigue Scale | 24.4571 | 16.3429 | 1.46 |

| Two minutes’ walk test | 62.500 | 81.1429 | 1.06 |

| CRP | 7.8486 | 3.7443 | 1.80 |

| Handgrip | 25.3429 | 28.8857 | 1.46 |

| WBC | 14491.4286 | 8222.8571 | 1.93 |

| Depression | 67.6000 | 50.8000 | 1.12 |

| FEV1/FVC | 288.6857 | 147.8571 | 0.69 |

| Quality of life | 45.5714 | 62.6857 | 1.60 |

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Muscle strength and general fatigue were assessed using several measures. The handgrip test was used to measure grip strength, which can serve as an indicator of overall physical strength and potential fatigue. The Chalder Self-report Questionnaire was administered at baseline, mid-point, and the end of the rehabilitation program to evaluate symptoms of fatigue, including tiredness, weakness, and lack of energy, and to assess mental status related to fatigue. Lower scores on this questionnaire indicate a decrease in the feeling of fatigue and improved energy levels in daily activities.

Psychological well-being and quality of life were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory and a Quality of Life Questionnaire specifically related to the COVID-19 epidemic. These questionnaires aimed to measure how the SER program affected participants' levels of depression and perceived quality of life. A lower score on the Beck Depression Inventory indicates a reduction in depressive symptoms, while an increase in scores on the Quality of Life Questionnaire indicates an improvement in the individual's understanding and perception of their living conditions.

We acknowledge the potential for placebo effects to influence observed outcomes, especially for subjective measures. Participants in exercise groups were aware of their active engagement, potentially generating positive expectations that contributed to self-reported benefits. While objective markers were used, future research could explore these non-specific effects through designs incorporating sham or active control conditions.

Physical condition was evaluated using the two-minute walk test to measure general physical fitness and exercise capacity, and spirometry to assess lung function, specifically FEV1, FVC, and the FEV1/FVC ratio. The handgrip test, as mentioned, also contributed to the assessment of physical condition by measuring grip strength. The values obtained from these tests provided indicators related to general physical capacity, respiratory function, and muscle strength.

It is important to note that the pre-tests were conducted approximately one day before each patient's hospital discharge. At this time, due to the acute phase of infection and inflammation, levels of WBC and CRP in the patients' bodies were still elevated above the normal limit. Post-tests were conducted approximately eight weeks after hospital discharge, by which time CRP had cleared from the body and both WBC and CRP levels had returned to their normal ranges.

As shown in Table 3, P-values are lower than 0.005 in the table of tests of between-subject effects, which means there was a significant difference in dependent variables between the control and experimental groups. It also shows the result of within-subject contrasts, and with 95.0% confidence intervals, there was a significant difference in dependent variables between the pre-test and post-test.

| Variables | Total | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | |

| Chalder Fatigue Scale | 0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| Two minutes’ walk test | 0.0008 | 0.0003 |

| CRP | 0.0008 | 0.0008 |

| Handgrip | 0.0007 | 0.0003 |

| WBC | 0.0005 | 0.0005 |

| Depression | 0.0001 | 0.0008 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.0008 | 0.0000 |

| Quality of life | 0.0001 | 0.0009 |

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

5. Discussion

Fatigue is a prevalent consequence of illness, often leading to long-term physical, mental, and social impairments. It is understood as a result of the body's diminished capacity to handle the physiological stress imposed by disease, affecting various bodily systems. Consequently, fatigue is broadly categorized into central fatigue, originating within the central nervous system, and peripheral fatigue, which arises from outside the central nervous system (4). Given that diverse diseases induce physiological stress, including cellular damage and systemic disruption, residual effects, such as fatigue, are likely to manifest, particularly when the body lacks sufficient recovery and appropriate treatment.

It is important to note that while the underlying causes of fatigue may differ across various diseases, its manifestations and management strategies can be remarkably similar. Clinically, fatigue is identified by a constellation of symptoms, including increased muscle soreness, reduced stress tolerance, sleep disturbances, lack of energy, emotional lability, pervasive tiredness, exhaustion, lethargy, decreased motivation, and negative cognitive patterns. Management approaches for fatigue typically involve comprehensive strategies such as complete rest, dietary adjustments and supplementation, physical rehabilitation, psychological support, and, when necessary, medication under medical supervision (16).

A significant number of individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 continue to experience persistent symptoms, a condition formally termed "Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC)". According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), individuals who experienced more severe acute illness are at a higher risk of developing PASC symptoms, which can persist for several months or even years. Fatigue is a frequently reported symptom among those with PASC (13).

In the comprehensive management of long-term complications following infectious diseases like COVID-19, exercise and physical rehabilitation occupy a crucial role alongside medication, proper nutrition, and rest. Building upon this understanding, we hypothesized that a specifically SER program would positively influence indicators related to post-COVID-19 fatigue. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate the effects of SER on the immune system, muscle damage, and mental health, all of which are known contributors to PASC (17, 18).

5.1. Understanding the Intertwined Roles of Immunity, SARS-CoV-2, and Selected-Exercise-Rehabilitation

The body's initial defense against SARS-CoV-2 is orchestrated by the innate immune system, acting as the primary barrier against pathogens. This system identifies the virus through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) on the viral surface. This recognition triggers the rapid synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, essential for initiating inflammation and recruiting other immune cells to the infection site. Alveolar and interstitial macrophages in the lungs, frequently affected by SARS-CoV-2, are among the first responders, engaging in phagocytosis, cytokine production, and antigen presentation.

Following the initial innate response, the adaptive immune response develops, typically appearing around 5 - 7 days post-infection. This phase involves the activation of antigen-specific T-cells, including CD4+ helper T-cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells, vital for recognizing and eliminating virus-infected cells and supporting B cell antibody production. Detectable antibody production by B-cells, including IgM, IgA, and IgG against SARS-CoV-2, usually emerges around 8 - 12 days after infection (19, 20).

A major contributor to the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 is an excessive and dysregulated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, often described as a "cytokine storm". This hyperinflammation arises from an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses, leading to widespread inflammation and potential multi-organ damage. The immune response to SARS-CoV-2, particularly in severe cases, can result in various systemic effects manifesting as disease symptoms. Lymphocyte depletion, or lymphopenia, is commonly observed and serves as an early indicator of high disease severity.

Histopathological examination of severely affected lungs frequently reveals edema, fibrosis, hyaline membrane formation, and lymphocytic interstitial infiltration into the alveoli, all consequences of the intense immune response. The intricate interplay of these cellular and humoral components of the immune response in severe COVID-19 ultimately culminates in systemic inflammation, organ damage, and fatigue (21, 22).

The SER programs can support the restoration of immune system function after viral infection through several key mechanisms. Regular participation in a SER program improves blood circulation, thereby enhancing the transport of immune cells throughout the body and facilitating more efficient pathogen detection and clearance. Exercise in general has the capacity to influence the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, potentially shifting the immune environment towards one conducive to recovery. The SER, as a moderate-intensity exercise program, is also known to help mitigate chronic inflammation, a state that can impair optimal immune function. By reducing the levels of stress hormones, which can exert immunosuppressive effects, exercise contributes to a more balanced immune response.

Additionally, regular exercise training reduces CRP levels both directly, by balancing inflammatory cytokine production, and indirectly, by increasing insulin sensitivity, improving endothelial function, and reducing body weight. Exercise has been linked to lower levels of inflammatory markers like TNF-alpha and CRP (20, 23, 24).

The SER should be prescribed cautiously and individualized, considering the patient's initial disease severity, the specific profile of their persistent symptoms, any pre-existing health conditions, and their current functional capacity. A gradual progression of both the intensity and duration of exercise within the SER program helps to avoid overexertion, which could potentially have adverse effects on the immune system. Continuous monitoring of symptoms and physiological responses during exercise sessions is also vital to ensure the safety and effectiveness of the rehabilitation program.

While the potential risks and contraindications associated with rehabilitation exercises for COVID-19 patients concerning their immune response must be considered, the positive influence of rehabilitation exercises on the immune system during COVID-19 recovery is often accompanied by observed improvements in immune function and various clinical outcomes, which are intertwined with other aspects of fatigue (24-26).

5.2. Understanding the Intertwined Roles of Muscle Damage, SARS-CoV-2, and Selected-Exercise-Rehabilitation

Fatigue is one of the most commonly reported and often most debilitating long-term complaints among individuals who have recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection. This fatigue is characterized by an overwhelming sense of tiredness and a lack of energy that can significantly impact an individual's ability to perform daily activities. The potential duration of muscle weakness following COVID-19 varies considerably. In cases of mild infection, acute weakness may resolve within approximately 2 to 3 weeks. The physiological basis of fatigue in COVID-19 is likely multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of various bodily systems, with muscle damage being a significant factor (27).

The mechanisms by which COVID-19 induces muscle damage are multifaceted, encompassing both potential direct effects of the virus on muscle tissue and a range of secondary consequences arising from the infection and the host response. Initially, concerns focused on the possibility of direct viral invasion of muscle cells. The ACE2 receptor, known as the primary entry point for SARS-CoV-2 into human cells, is indeed expressed in skeletal muscles (2). The interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with ACE2 can disrupt the delicate balance of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS). The ACE2 normally converts Angiotensin II (Ang II) to Angiotensin 1 - 7 (Ang 1-7), which has protective effects on muscle tissue. However, when SARS-CoV-2 binds to and potentially downregulates ACE2, it can lead to an increase in Ang II levels and a decrease in Ang 1-7, potentially contributing to muscle atrophy and fibrosis. Notably, one autopsy study detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the diaphragm muscle of patients in the acute phase, indicating the presence of the virus in muscle tissue, particularly respiratory muscles, which can lead to respiratory muscle damage and reduced respiratory function (28, 29).

Secondary mechanisms appear to play a more prominent role in the development of muscle damage associated with COVID-19. A significant factor is the systemic inflammatory response, often referred to as a "cytokine storm". Furthermore, the prolonged immobility that often accompanies severe COVID-19, whether due to hospitalization or the severity of symptoms, leads to muscle disuse atrophy and subsequent weakness. Additionally, certain medications used in the treatment of COVID-19, such as corticosteroids, can have side effects that contribute to muscle weakness and damage.

Metabolic dysfunction, particularly affecting the mitochondria — the powerhouses of cells — can also impair the energy supply to muscles, resulting in weakness and reduced exercise tolerance. Inflammation-induced muscle dysfunction, where the ongoing inflammatory response directly interferes with muscle contractility and function, is another contributing factor. Hypoxia, or a deficiency in oxygen supply to the tissues, which can occur in severe COVID-19, further exacerbates muscle weakness by impairing oxidative phosphorylation, the primary process for energy generation in muscles (30, 31).

Studies have consistently demonstrated a substantial reduction in both absolute and relative muscle strength measurements in patients with long COVID-19 syndrome compared to control participants. Peripheral muscle strength, as well as respiratory muscle strength, is often diminished in individuals shortly after hospitalization for COVID-19. Muscle wasting and a resultant loss of strength are recognized as common consequences, particularly in cases of severe COVID-19.

COVID-19 infection triggers a significant disruption in the body's redox balance, leading to a state of heightened oxidative stress. This imbalance arises from an increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) coupled with a diminished capacity of the host's antioxidant defense mechanisms. The intense inflammatory response associated with COVID-19, often referred to as a cytokine storm, also significantly contributes to and perpetuates oxidative stress. The release of a large number of pro-inflammatory cytokines is often accompanied by an increase in ROS production, further tipping the redox balance towards oxidative stress (32, 33).

The SER programs employ various mechanisms to counteract the muscle damage associated with COVID-19. As mentioned, SER has demonstrated the potential to reduce inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and CRP, which serve as markers of systemic inflammation and are significant contributors to fatigue in long COVID. By reducing these inflammatory markers, SER can help mitigate the effect of the inflammatory response on muscle damage, as evidenced by changes in WBC and CRP levels in our study.

Specifically, resistance training within the SER program (e.g., using body weight, light resistance bands, or very light weights, focusing on major muscle groups) serves as a potent stimulus for muscle protein synthesis, a fundamental process for repairing damaged muscle fibers and building new muscle tissue (34, 35). Even for severely ill patients, initiating early mobilization as part of SER during the acute phase of COVID-19 can help to mitigate the development of muscle weakness and accelerate recovery.

Resistance training within SER, alongside other components, has also demonstrated positive effects on muscle strength and overall functional outcomes in post-COVID-19 patients, as shown by improvements in handgrip strength and the two-minute walk test. Furthermore, the importance of maintaining an adequate protein intake alongside exercise underscores the need for a comprehensive approach to rehabilitation that includes nutritional support to optimize the body's ability to effectively repair and rebuild muscle tissue (3, 11, 34).

Additionally, SER improves muscle strength and endurance, which is particularly beneficial for individuals who have experienced prolonged periods of inactivity due to illness. By individualizing the training to incorporate patients' daily routine activities, SER leads to increased functional capacity, enabling individuals to perform activities of daily living with greater ease and independence (17, 36). This can be reflected in the results of Quality of Life questionnaires.

Our findings suggest that initiating pulmonary exercises within SER (e.g., breathing exercises such as diaphragmatic breathing, pursed-lip breathing, and the use of an incentive spirometer) as soon as feasible is crucial for strengthening respiratory muscles, which can be weakened by the virus and prolonged immobility (28). This can have a preventative effect on the development of long-term muscle wasting and weakness, as indicated by changes in FEV1/FVC. Engaging in activity early in the recovery process can also help to maintain existing muscle mass and function, potentially mitigating the severity of long-term sequelae and promoting a more complete recovery.

In turn, this can significantly enhance blood flow and the delivery of oxygen to skeletal muscles. This improved circulation is crucial for the proper function and repair of muscle tissues and helps to reduce ROS accumulation (15). Regular participation in an aerobic component of the SER program (e.g., short bouts of walking added to other training) is a powerful stimulus for mitochondrial biogenesis, the process through which new mitochondria are created within cells. It also enhances the efficiency of existing mitochondria in muscle cells. Improvements in mitochondrial function, achievable through exercise, may result in a more efficient energy metabolism within the muscles, potentially leading to a normalization of lactate levels and reducing the accumulation of ROS. Furthermore, the aerobic part of the SER program improves cardiorespiratory fitness, which increases the body's capacity to deliver oxygen to working muscles. This enhanced oxygen delivery can significantly reduce the feeling of fatigue that occurs during physical activity (11, 18).

5.3. Understanding the Intertwined Roles of Mental Health, SARS-CoV-2, and Selected-Exercise-Rehabilitation

COVID-19 may impair communication within the brain, potentially leading to suboptimal brain function and fatigue. Changes in the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain, such as dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine, which play crucial roles in mood, motivation, and muscle function, may also contribute to fatigue. Emerging research also suggests that brain inflammation itself can trigger extreme muscle weakness and fatigue after infections. Hormonal imbalances and reduced levels of ACE2, potentially affecting communication between nerves and muscles, represent further areas of investigation into the complex physiological basis of post-COVID fatigue (18).

Studies have shown that patients experiencing post-COVID fatigue exhibit underactivity in specific cortical circuits within the brain, as well as dysregulated autonomic functions. Interestingly, inspiratory muscle training, a specific type of exercise, has demonstrated promise in improving autonomic function in individuals suffering from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and PASC, also known as long COVID. Regular participation in physical activity may also help to counterbalance the autonomic alterations that have been described in patients with long COVID.

The potential of exercise to regulate the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) suggests a mechanism for reducing fatigue that extends beyond the direct effects on muscle tissue. By addressing the systemic dysregulation that contributes to fatigue in long COVID, exercise may offer a more comprehensive approach to symptom management. It is theorized that by improving the balance within the ANS, exercise might help to restore normal physiological responses that are involved in the experience of fatigue.

Fatigue in the context of long COVID is often a complex symptom with multiple contributing factors, including central (related to the brain and nervous system), psychological, and peripheral (related to the muscles and body) aspects (37).

Firstly, SER has well-documented benefits for mental health, including its ability to reduce feelings of anxiety and depression (e.g., incorporating meditations and yoga training in every session), both of which can significantly contribute to the perception of fatigue. Secondly, the increase in aerobic capacity that results from regular exercise can also lead to a decrease in the psychological problems that are commonly observed in individuals with long COVID (4).

Furthermore, a designed exercise program like SER has the potential to stimulate brain plasticity and enhance overall psychological well-being, which may help to mitigate the central components of fatigue. In addition, by reducing the fear of physical activities and tailoring exercises to the patients' capabilities, and by incorporating both group (in the last 3 weeks) and individual (in the first 5 weeks) sessions conducted at home and in a rehabilitation clinic, the SER program acts similarly to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which has also demonstrated efficacy in reducing the severity of fatigue and improving physical and social functioning in affected individuals.

Mental health and fatigue are frequently interconnected, and SER can improve mood and reduce psychological distress, which in turn can have a positive impact on an individual's perceived levels of fatigue. Regularly engaging in SER programs can enhance self-regulation, self-judgment, and self-discipline. Furthermore, improved physical efficiency can foster self-mastery, a crucial criterion for promoting positive psychological outcomes (11, 38).

Since COVID-19 is an infectious disease, the results of this study, briefly illustrated in Figure 2, may have broader applicability to patients with other infectious diseases as well as different strains of COVID-19. Given that there is currently no definitive cure for COVID-19 and the long-term and short-term effects of the disease are still being elucidated, this exercise-rehabilitation program presents a potentially non-invasive and practical approach to mitigating the consequences of the disease. Furthermore, considering the economic burden that infectious diseases and their sequelae place on society, exercise rehabilitation, such as the SER program, offers a means to reduce disease complications like fatigue, thereby potentially alleviating some of this economic pressure.

5.4. Conclusions

Ultimately, this article aimed to investigate the effect of SER on the long-term consequences of infectious diseases such as COVID-19, especially focusing on fatigue. Based on existing evidence, factors such as immune response, muscle damage, and mental health influence long-term post-COVID-19 fatigue. Based on the obtained results and data, SER can help reduce the consequences after COVID-19 by improving immune system function and mitigating its effects, reducing muscle damage factors, and enhancing oxidative stress processes, mitochondrial activity, and physical fitness, while also improving mental and social health.

5.5. Limitations and Generalizability

Despite the significant findings, several limitations warrant consideration regarding the generalizability of our results. Our study population was primarily composed of middle-aged COVID-19 patients experiencing post-COVID-19 fatigue, which may limit the direct applicability of these findings to different infectious diseases. Furthermore, the intervention was delivered in a highly controlled laboratory environment, potentially enhancing internal validity but potentially reducing ecological validity, given that real-world implementation might occur in less structured settings. The relatively short follow-up period of eight weeks also restricts our ability to assess the long-term sustainability of the observed effects of SER. Future research should aim to recruit more heterogeneous samples, investigate the intervention's effectiveness in varied practical settings, and incorporate extended follow-up periods to strengthen the generalizability and durability of these findings.