1. Background

Physical inactivity poses a widespread global challenge that requires comprehensive and often expensive initiatives to address the risks of chronic diseases associated with it (1). Walking behavior is influenced by environmental temperature (2), with temperature serving as a crucial factor affecting daily step counts. However, there is still an incomplete understanding of the variations in the year-round daily step counts of an individual in relation to meteorological conditions. The Temperature-Humidity Index (THI) demonstrated a stronger association than temperature alone in explaining seasonal variations in daily step counts, as evidenced by a study utilizing two-piece linear regression analysis (3). Ravagnolo et al. emphasized the utmost significance of maximum daily temperature (AT) and minimum daily relative humidity (RH) when calculating THI to measure heat stress (4, 5). However, our preliminary investigation, based on weather records from Japan, revealed that THI derived from maximum AT and maximum daily RH was more effective than that computed using the average temperature and lowest RH recorded within a day. Consequently, THI values were estimated using average AT and average daily RH. Initially, THI was calculated using the formula provided by the National Research Council (NRC, 1971) (6). Although the relationship between average AT and daily step count has already been reported, the associations between the average, maximum, and minimum values of the THI and step count remain unclear. Moreover, potential sex differences have not been sufficiently investigated.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the sex differences in the relationship between meteorological conditions and objectively measured daily step counts among Japanese individuals residing in a community.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This study constituted a secondary analysis aimed at comprehensively examining the correlation between meteorological conditions and objectively measured daily step counts. The analysis utilized extensive year-round data obtained from an observational study, involving a significant sample size of 2,076 participants. The study protocol received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Biomedical Research and Innovation, Kobe, Japan (ethics approval number: H191024). The initial informed consent obtained from participants covered the use of data for secondary analyses. All data were fully anonymized to protect individual privacy. Original data were gathered from December 2007 to November 2008. This study was a secondary analysis. The present original study mainly aimed to investigate the association between step counters with incentives and exercise habits among residents of Kobe city. Daily step count data were collected from 50 step counter stations installed throughout the city. Participants were recruited through public outreach efforts conducted by the research group. The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) Aged 20 years or older; (2) no restriction based on sex; (3) sufficient cognitive ability and physical capacity to engage in walking; and (4) provision of written informed consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Having medical conditions that contraindicate physical activity; (2) being advised by a physician to restrict physical activity; and (3) being deemed unsuitable for participation by a physician. The required sample size to detect a statistically significant difference between two receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves [area under the curve (AUC = 0.60 vs. AUC = 0.65)] with 95% power and a two-sided significance level of 0.05 was estimated using the power.roc.test function from the pROC package in R. Assuming a 1:1 ratio of positive to negative cases, the calculation indicated that 204 positive cases and 204 negative controls (total n = 408) would be required.

3.2. Measures

Weather records were obtained from the official website of the Japan Meteorological Agency. The THI values were computed using the mean AT and mean daily RH. The formula employed for calculating THI was as follows: THI = (0.8 × AT) + [(RH/100) × (AT - 14.4)] + 46.4 (7, 8). The THI was calculated using the mean AT and RH, following the NRC (1971) formula, which has been widely used in human biometeorological and occupational health research. The use of mean values was chosen to represent the average thermal exposure throughout the day, as opposed to maximum or minimum values which may capture only brief periods of extreme conditions. This approach aligns with previous studies evaluating chronic environmental exposure and daily behavioral responses such as physical activity.

To gather data on various behavioral and lifestyle aspects of study participants, including their dietary, smoking, and drinking habits, frequency of exercise, and sleep patterns, self-administered questionnaires were utilized. These questionnaires were administered using a standardized assessment tool (9-11). Healthy lifestyle behaviors were assessed using the Eight Health Practices proposed (10). This index includes the following eight components: (1) Non-smoking; (2) moderate alcohol consumption; (3) regular breakfast intake; (4) adequate sleep duration (7 - 8 hours per night); (5) work duration of less than 9 hours per day; (6) regular physical activity (at least once per week); (7) a balanced diet; and (8) moderate levels of psychological stress. Each component was scored as 1 (healthy behavior) or 0 (unhealthy behavior).

3.3. Data Analysis

In contrast to individuals classified as sedentary (< 5,000 steps/day) at the baseline, those categorized as minimally active (5,000 - 7,499 steps/day), somewhat active (7,500 - 9,999 steps/day), and active (≥ 10,000 steps/day) displayed significant differences (12-15). Quadratic fit analysis was employed for statistical analysis of the data. Additionally, the ROC curve was used to establish the optimal threshold for distinguishing 10,000 steps in men and 8,000 steps in women. The optimal AUC, sensitivity, and specificity were calculated through ROC curve analyses. The optimal cut-off value for the target variable was determined as the point on the ROC curve closest to the upper-left corner (0, 1). Diagnostic accuracy using the area under the ROC curve was categorized as follows: < 0.5 (test not useful), 0.5 - 0.6 (bad), 0.6 - 0.7 (sufficient), 0.7 - 0.8 (good), 0.8 - 0.9 (very good), and 0.9 - 1.0 (excellent). The magnitude of Cohen’s d was interpreted according to conventional thresholds: A value of 0.2 indicates a small effect size, 0.5 represents a medium effect size, and 0.8 or higher reflects a large effect size. The reported values were presented as mean ± SD, and significance was determined based on P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2). The following packages were utilized: Data.table (v1.14.6), tidyverse (v1.3.2), pROC (v1.18.0), lme4 (v1.1-33), car (v3.1-2), ggplot2 (v3.4.0), knitr (v1.42), and gridExtra (v2.3). Given the observational design of the study, blinding of participants and investigators was not implemented. Nevertheless, in order to reduce analytic bias, the data analyst was blinded to the exposure/outcome status during statistical analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The mean age of male participants was 62.4 years, whereas female participants had an average age of 60.6 years. Furthermore, men had a significantly higher Body Mass Index (BMI) compared to women. Additionally, men recorded a significantly higher mean number of steps per day than women. Regarding lifestyle habits unrelated to exercise and sleep, women exhibited healthier practices than men. Men were observed to take a higher number of medications for hypertension and diabetes, whereas women demonstrated a higher prevalence of medication use for dyslipidemia than men (Table 1).

| Variables | Men | Women | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 62.4 ± 10.2 | 60.6 ± 10.1 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 ± 2.7 | 22.5 ± 3.0 | < 0.001 |

| Mean number of steps (steps) | 9516 ± 4536 | 7451 ± 2901 | < 0.001 |

| Healthy lifestyle (%) | |||

| Exercise: Twice a week or more | 65.1 | 54.9 | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption: Sometimes or never | 42.0 | 86.2 | < 0.001 |

| Non-smoking | 84.8 | 98.1 | < 0.001 |

| Sleeping pattern: 7 or 8 h/night | 53.7 | 47.4 | 0.011 |

| Nutritional status: Balanced | 42.8 | 51.5 | < 0.001 |

| Eat breakfast: Everyday | 94.1 | 96.6 | 0.013 |

| Working pattern: ≤ 9 h/d | 82.6 | 92.3 | < 0.001 |

| Subjective stress: Moderate | 58.0 | 64.0 | 0.012 |

| Medication | |||

| Hypertension | 24.1 | 16.8 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 5.9 | 2.4 | < 0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 8.6 | 13.4 | 0.002 |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

a A P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

4.2. Receiver Operating Characteristic

In men, ROC curve analysis revealed that for achieving 10,000 steps/day, the cut-off points were 17.4°C (maximum temperature), 15.7°C (mean temperature), and 12.4°C (minimum temperature), with corresponding AUC values of 0.732, 0.713, and 0.691, respectively. Additionally, ROC curve analysis indicated cut-off points of 63.1 (maximum THI), 59.7 (mean THI), and 52.3 (minimum THI) for achieving 10,000 steps/day in men, yielding AUC values of 0.724, 0.711, and 0.694, respectively (Table 2). We evaluated potential confounding factors, including age, BMI, comorbidities, and medication use. Among these, only BMI in women showed a significant effect on the target daily step count. In women with BMI < 25, the cut-off values for maximum, mean, and minimum temperature were 18.3°C, 15.7°C, and 12.4°C, respectively, with AUCs of 0.652, 0.637, and 0.621. Sensitivity and specificity for maximum temperature were 0.711 and 0.594, respectively. In contrast, among women with BMI ≥ 25, the corresponding temperature cut-off values were slightly higher at 20.2°C, 15.8°C, and 12.4°C, but AUCs were lower: 0.609, 0.597, and 0.588. Notably, this group showed higher sensitivity (0.778 - 0.833) but lower specificity (0.470 - 0.500) compared to the lower BMI group. Regarding THI, women with BMI < 25 had cut-off values of 63.10, 59.50, and 52.50 for maximum, mean, and minimum THI, with AUCs of 0.643, 0.635, and 0.623, respectively. Sensitivity ranged from 0.687 to 0.721, and specificity from 0.533 to 0.582. Among those with BMI ≥ 25, the cut-off values were 65.45, 59.70, and 55.05, with slightly lower AUCs (0.599 - 0.585). Sensitivity remained high (0.778 - 0.833), but specificity was again lower (0.467 - 0.485).

| Variables | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off Value | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Cut-off Value | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| Temperature | ||||||||

| Maximum | 17.4 | 0.732 | 0.785 | 0.637 | 20.2 | 0.645 | 0.657 | 0.580 |

| Mean | 15.7 | 0.713 | 0.722 | 0.656 | 15.7 | 0.630 | 0.687 | 0.545 |

| Minimum | 12.4 | 0.691 | 0.699 | 0.637 | 12.6 | 0.613 | 0.657 | 0.540 |

| THI | ||||||||

| Maximum | 63.1 | 0.724 | 0.756 | 0.643 | 66.1 | 0.637 | 0.657 | 0.570 |

| Mean | 59.7 | 0.711 | 0.722 | 0.650 | 59.7 | 0.626 | 0.687 | 0.540 |

| Minimum | 52.3 | 0.694 | 0.775 | 0.592 | 55.4 | 0.615 | 0.657 | 0.540 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; THI, Temperature-Humidity Index.

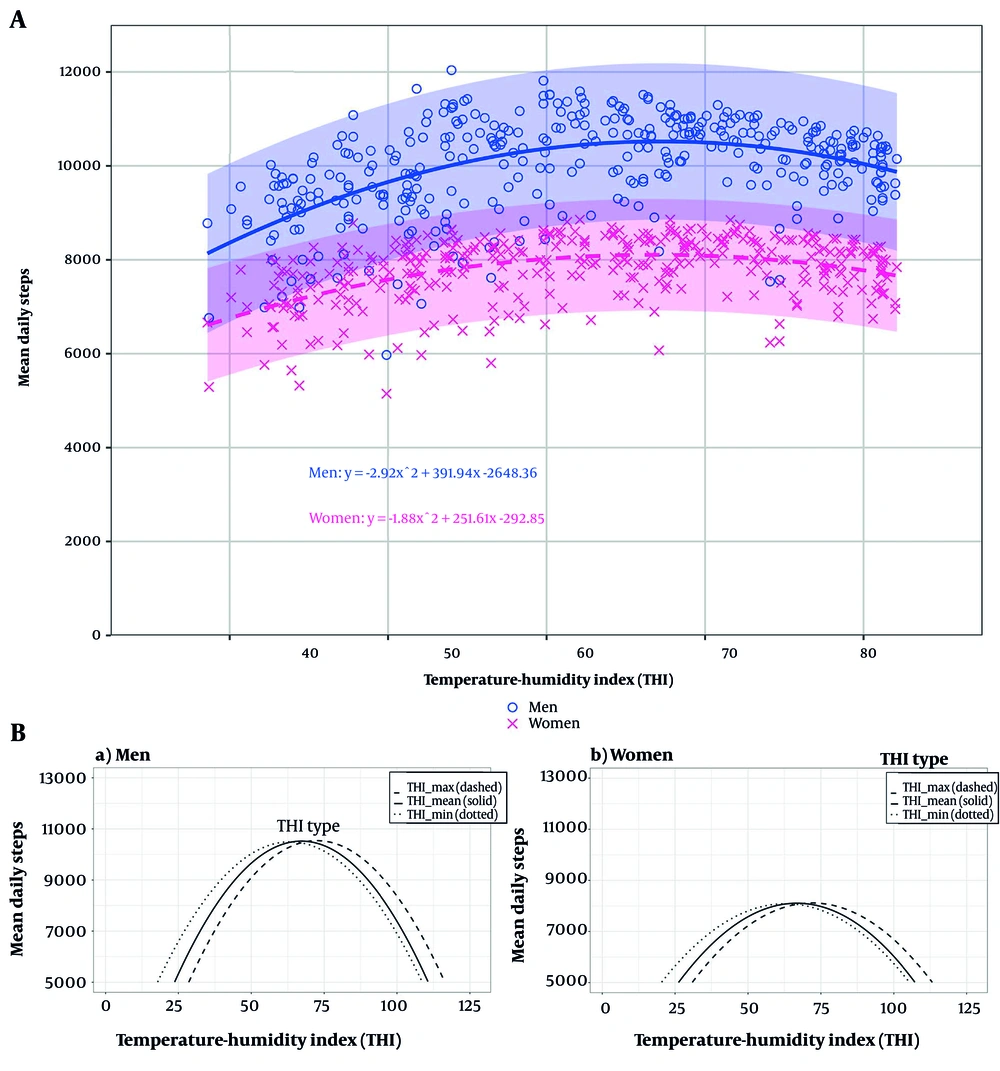

4.3. Quadratic Fit Analysis

The daily steps count of achievers displayed a negative linear regression with regard to humidity and 10,000 steps/day, while both the maximum and minimum temperatures demonstrated a negative quadratic curve (Figure 1A and B). The coefficient of determination (R2) measures the accuracy with which a statistical model predicts an outcome. In the context of quadratic fit analysis, men exhibited higher R2 values for maximum, mean, and minimum temperatures compared to women. Additionally, a similar trend was noted for THI, where maximum THI showed the highest R2 values for both sexes (Table 3). The effect sizes for sex differences in THI and temperature variables were evaluated using Cohen’s d. For men, large effect sizes were observed for THI maximum (d = 0.756), mean (d = 0.688), and minimum (d = 0.587), as well as for temperature maximum (d = 0.780), mean (d = 0.688), and minimum (d = 0.587). For women, effect sizes were slightly lower but remained in the medium-to-large range: THI maximum (d = 0.621), mean (d = 0.561), and minimum (d = 0.486); temperature maximum (d = 0.657), mean (d = 0.561), and minimum (d = 0.486).

| Variables | Men | Women | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Daily Steps | Parameters | R2 | Pearson’s r | P-Value (r) | Peak Daily Steps | Parameters | R2 | Pearson's r | P-Value (r) | |

| Temperature | ||||||||||

| Maximum | 10,511 | 24.4 | 0.303 | 0.420 | < 0.001 | 8,098 | 24.0 | 0.241 | 0.360 | < 0.001 |

| Mean | 10,480 | 20.8 | 0.255 | 0.380 | < 0.001 | 8,081 | 20.4 | 0.205 | 0.326 | < 0.001 |

| Minimum | 10,447 | 18.1 | 0.199 | 0.327 | < 0.001 | 8,055 | 17.7 | 0.155 | 0.276 | < 0.001 |

| THI | ||||||||||

| Maximum | 10,541 | 72.5 | 0.315 | 0.400 | < 0.001 | 8,115 | 72.1 | 0.251 | 0.343 | < 0.001 |

| Mean | 10,521 | 67.2 | 0.279 | 0.370 | < 0.001 | 8,106 | 66.8 | 0.226 | 0.319 | < 0.001 |

| Minimum | 10,494 | 63.3 | 0.231 | 0.328 | < 0.001 | 8,086 | 62.9 | 0.183 | 0.280 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: R2, coefficient of determination; THI, Temperature-Humidity Index.

This study marks the first exploration of sex disparities in the correlation between meteorological conditions and the quantitatively measured daily step counts of individuals living within a Japanese community.

5. Discussion

5.1. Sex Differences

Extensive research has consistently shown that individuals who maintain a regular walking habit, especially those exceeding a daily threshold of 8,000 steps, experience a reduction in mortality rates (16). In this study, men averaged approximately 10,000 steps/day, while women averaged approximately 8,000 steps/day. Data from Nakanojo study (17), utilizing pedometer/accelerometer data, revealed that both sexes exhibit a decreased prevalence of health issues, particularly hypertension and hyperglycemia, when engaging in activities surpassing a threshold range of daily step counts and/or duration of activity > 3 metabolic equivalent of task units. The recommended range for optimal health outcomes is between 8,000 and 10,000 steps/day, specifically regarding components related to metabolic syndrome. Reports have indicated significant sex differences in the association between a daily increment of 1,000 steps and a substantial reduction in blood pressure among women diagnosed with type 2 diabetes; however, the evidence remains inconclusive for men (18).

Baseline data revealed a notable disparity in exercise habits and daily step counts between men and women, with men showing significantly higher levels for these parameters. The underlying causes for this phenomenon remain uncertain and may be attributable to factors such as the relatively advanced age and higher BMI of the men compared to women in this study, as well as the greater prevalence of medication use for hypertension and diabetes among men. On the other hand, engaging in exercise has been found to improve specific sleep outcomes among adults (19). College freshmen men in the U.S. have also been reported to exhibit higher physical activity levels, lower stress levels, and poorer sleep quality than freshmen women (20). Consequently, the difference in exercise habits between the sexes may contribute to the variation in sleep quality experienced by men and women.

Possible explanations for the observed differences in this study include physiological factors (e.g., sex-related differences in thermoregulation and muscle strength with aging), behavioral factors (e.g., motivation for outdoor activities and self-efficacy), sociocultural factors (e.g., gender role norms influencing behavior), and environmental factors (e.g., patterns of using daily living spaces) (21-23). Specifically, older women may have a stronger indoor orientation and experience greater psychological barriers to heat exposure or slippery surfaces compared to men. These tendencies may partly explain the observed sex differences in behavioral responses to heat and humidity, and warrant further investigation in future studies.

Interestingly, the peak step counts were observed at different THI values by sex: 59.7 for men and 66.1 for women. This discrepancy may suggest sex-specific sensitivity to thermal environments; however, potential confounding factors such as differences in age and BMI should also be considered. In our sample, men were older and had a higher mean BMI compared to women, which may have contributed to reduced physical activity under warmer or more humid conditions. Older adults and individuals with higher BMI may experience greater thermal discomfort or cardiovascular strain during physical exertion, potentially lowering their activity levels at higher THI values. Therefore, it is plausible that the observed sex differences in the THI-step count relationship may be partially mediated by physiological or demographic factors. Future analyses stratified by age and BMI, or statistical adjustments for these variables, may help clarify whether thermal sensitivity or underlying characteristics primarily explain the variation in activity patterns.

5.2. Temperature-Humidity Index

The THI has been utilized as a measure since the early 1990s, encompassing the combined impact of environmental temperature and RH. This serves as a valuable and straightforward approach for evaluating the potential risks associated with heat stress. The THI level is categorized into various classes that indicate the intensity of heat stress. However, the precise definitions of these THI levels vary among different researchers. For example, designated a THI value below 71 as being in the comfort zone, values ranging from 72 to 79 as mild stress, 80 to 89 as moderate stress, and values above 90 as severe stress (24). Alternatively divided THI into two categories: 79 ≤ THI ≤ 83 was categorized as a dangerous situation, and THI ≥ 80 as an emergency situation (25). In another study classified a THI value of 70 ≤ THI ≤ 74 as uncomfortable, 75 ≤ THI ≤ 79 as very uncomfortable, and THI ≥ 80 as serious discomfort (26).

In this study, three THI indicators were assessed, namely the maximum, the mean, and the minimum THI. Interestingly, the highest THI value exhibited the greatest AUC value for both men and women. Consequently, we reasoned that the number of daily steps is primarily influenced by the highest THI. Hino et al. probed the correlation between the monthly mean temperature and THI, revealing that THI outperforms temperature as a predictor of daily steps. However, Hino et al. (27) did not investigate the maximum THI, minimum THI, and the mean number of steps per month. Our data reported here show that the maximum THI holds a stronger association with the daily steps count compared to the mean THI, marking a novel finding.

The R2 quantifies the degree of accuracy with which a statistical model anticipates an outcome. The quadratic fit analysis we undertook showed that men exhibited superior R2 values in terms of maximum, mean, and minimum temperatures compared to women. Furthermore, a similar pattern was observed for THI, with maximum THI displaying the highest R2 values for both sexes. Notably, our subgroup analysis among women by BMI category revealed that those with higher BMI may exhibit greater sensitivity to ambient thermal conditions. This observation suggests that body composition could partially explain the observed sex differences in environmental responsiveness. However, the specificity of environmental thresholds for predicting adequate daily step counts appeared to be lower in this subgroup, indicating that additional factors may influence behavioral adaptation to heat stress in women with higher BMI. These findings highlight the importance of considering individual-level physiological traits, such as BMI, alongside meteorological indices when interpreting physical activity patterns in response to environmental stressors.

5.3. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlighted the influence of meteorological factors, specifically maximum AT and THI, on the daily steps count. This information is considered invaluable for offering exercise guidance aimed at reducing the risk of lifestyle-related diseases, such as diabetes.

5.4. Limitations

This study has several limitations, including the use of self-administered questionnaires to assess lifestyle factors. However, it also has numerous strengths, such as the objective measurement of daily steps count, a one-year follow-up period, and the consideration of three values of THI (maximum, mean, and minimum). The THI formula employed in this study was originally developed by the NRC (1971) and has been widely used in environmental research. However, this index was not specifically validated for human thermoregulation or behavioral outcomes in contemporary Japanese populations. Future research should consider alternative or regionally calibrated indices that better capture thermal discomfort in diverse climatic and sociodemographic settings.

We adopted the THI formula developed by the NRC (1971) due to its simplicity, wide applicability, and compatibility with the meteorological data available for this study. While other indices, such as the wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT) or Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), may provide more precise estimates of human thermal stress, they often require additional environmental or physiological input variables not accessible in the current dataset. Future studies should consider incorporating such indices to enhance physiological accuracy.

Generalizability from our data may be limited due to the specific target population, namely Japanese adults residing in Kobe city, Japan. The generalizability of the present findings may be limited due to the participant recruitment method and eligibility criteria. Participants were recruited through public outreach by the research team, which may have introduced a self-selection bias, favoring individuals who were more health-conscious or motivated to engage in physical activity. Furthermore, inclusion criteria required participants to have sufficient cognitive and physical ability to walk independently, excluding individuals with significant physical or cognitive impairments. As a result, the sample may not fully represent the broader population of older adults, particularly those with frailty, comorbidities, or limited mobility. Future studies should consider broader recruitment strategies and more inclusive eligibility criteria to enhance external validity and ensure findings are applicable to more diverse populations, including those with varying functional capacities and health statuses.

As this study was conducted in Kobe, Japan — a region with a relatively temperate climate — the generalizability of these findings to areas with more extreme climates (e.g., tropical or arid zones) may be limited. Future research should investigate whether region-specific THI thresholds exist by replicating this analysis in other environmental contexts.