1. Introduction

Regular engagement in a high-intensity and demanding soccer regimen results in predictable and benign cardiac pathological changes. The structural and functional remodeling of the heart that results from such increased physical activity is collectively referred to as athlete’s heart (1). These changes are usually regarded as normal physiological and training-related adaptations in athletes that do not warrant further investigation, even if they can be categorized as pathological in non-athletes. Still, in certain cases, further evaluation may be needed to distinguish pathological conditions from normal adaptations (2). Evaluating an athlete’s electrocardiogram (ECG) remains a challenging task, as various physiological adaptations can overlap with conditions associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) or sudden cardiac death (SCD) (2). The most prominent cardiac abnormalities in athletes’ ECGs include T-wave inversion, ST-segment depression, and pathological changes within the QRS complex, whereas other abnormalities may also be observed (3). Researchers are increasingly emphasizing that clinicians who screen athletes should be able to differentiate ECG abnormalities resulting from high-intensity physical training from those indicative of increased cardiovascular risk for SCA/SCD (4). Although preparticipation examination is recommended before engaging in competitive sports to identify such changes, debate persists regarding the use of the ECG screening to detect disorders associated with SCD. This is particularly relevant to athletes of black African descent, who exhibit a higher rate of false-positive sport ECG abnormalities during screening compared to their white Caucasian counterparts (5).

This report presents two cases involving South African male professional soccer players, aged 26 (case A) and 23 (case B), who underwent preseason medical screening. The athletes were recruited from a research study examining the ECG profiles of black South African soccer players. Neither athlete was receiving treatment nor had a history of syncope, but athlete B reported intermittent palpitations and throbbing abdominal pain during soccer matches.

Black African athletes frequently exhibit greater left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) during preparticipation screenings. The higher prevalence of false-positive results in this population presents a dilemma, as it complicates risk stratification and may contribute to missed or misclassified cases of SCD. Therefore, this case report focuses on examining the resting sport ECG repolarization patterns typical of black South African professional soccer players. The black athlete variant is characterized by J-point elevation, convex ST-segment elevation, and T-wave inversions in leads V1 to V4 occurring in approximately 5% to 15% of black athletes (5). In another study done by Sheikh et al. (6), it also shows that black athletes tend to have 30% more probability of SCA with lateral T-wave inversion.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Case A

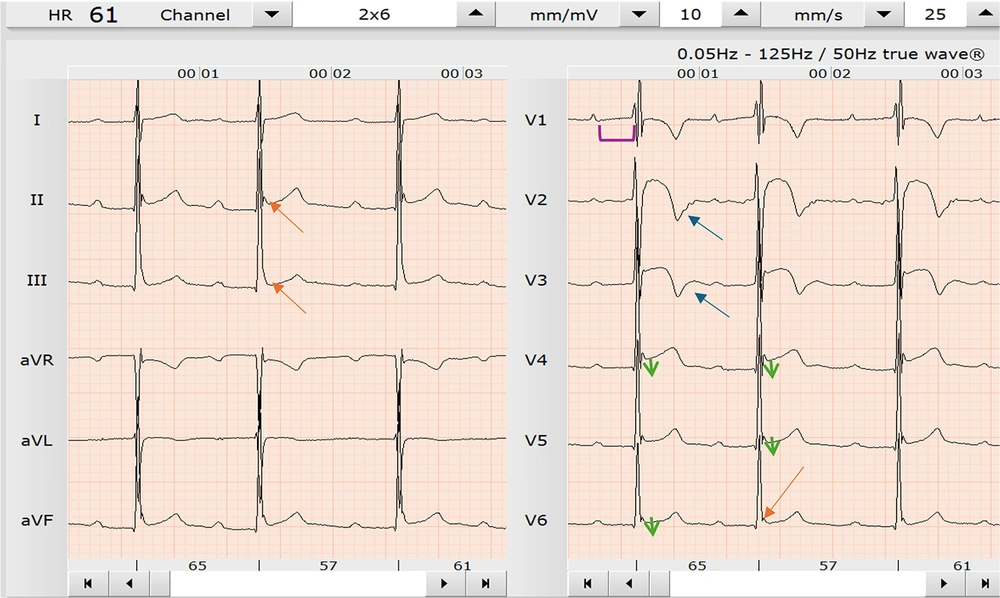

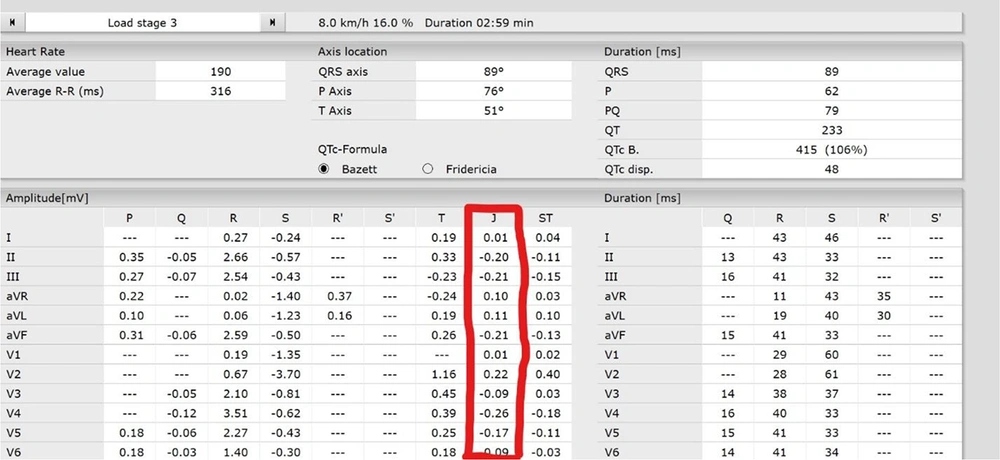

Athlete A is a 26-year-old South African male professional soccer player who presented for preseason medical screening. He was one of 105 players recruited for a research study examining the ECG profiles of black South African soccer players. During history taking, athlete A reported intermittent palpitations and throbbing abdominal pain during games. He noted that this abdominal pain was exacerbated by running and mostly experienced towards the end of a 90-minute soccer match, but he denied any history of collapsing on the field or experiencing chest pain. A 12-lead resting sport ECG test was performed on the athlete and analyzed using the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) international consensus standards for ECG interpretation in athletes. Common changes of T-wave inversion patterns for this population were observed, including inversions between leads V1-V6 and select limb leads (Figure 1). Specifically, athlete A presented with T-wave inversions in leads II, aVF, V2, V3, V4, V5, and V6 (Figure 1). These ECG changes were considered to be potentially pathological due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) with marked sinus bradycardia. Given these ECG abnormalities and the athlete’s reported symptoms, he was considered at high risk for SCA. According to the ESC international consensus standards for ECG interpretation in athletes, these changes are also classified as uncommon training-related changes. A stress ECG test was subsequently conducted to investigate the reported symptoms further (Figure 2). During the stress test, all the previously observed ECG changes were reversed, and no new T-wave inversions were noted. Although complex QRS changes were present, they were inconclusive and suggestive of a possible incomplete bundle branch block. The stress test was terminated due to the athlete's reproduction of the symptoms experienced during matches. These changes can also be attributed to exercise-induced vasodilation in skeletal muscle, which lowers systemic vascular resistance and increases cardiac output — resulting in reduced systolic blood pressure and more efficient blood delivery to the working muscles.

The athlete during a Bruce protocol stress test (load 8.0 km and gradient of 16%); this focuses on the precordial leads with no sign of any T-wave inversion. This is the same athlete displayed in Figure 1 [resting electrocardiogram (ECG)].

Based on these findings, athlete A is considered to exhibit features of athlete’s heart with a high risk for SCA/SCD per the ESC international consensus standards, and possible adaptations suggestive of HCM. He was therefore referred for an echocardiographic (ECHO) scan for further evaluation.

2.2. Case B

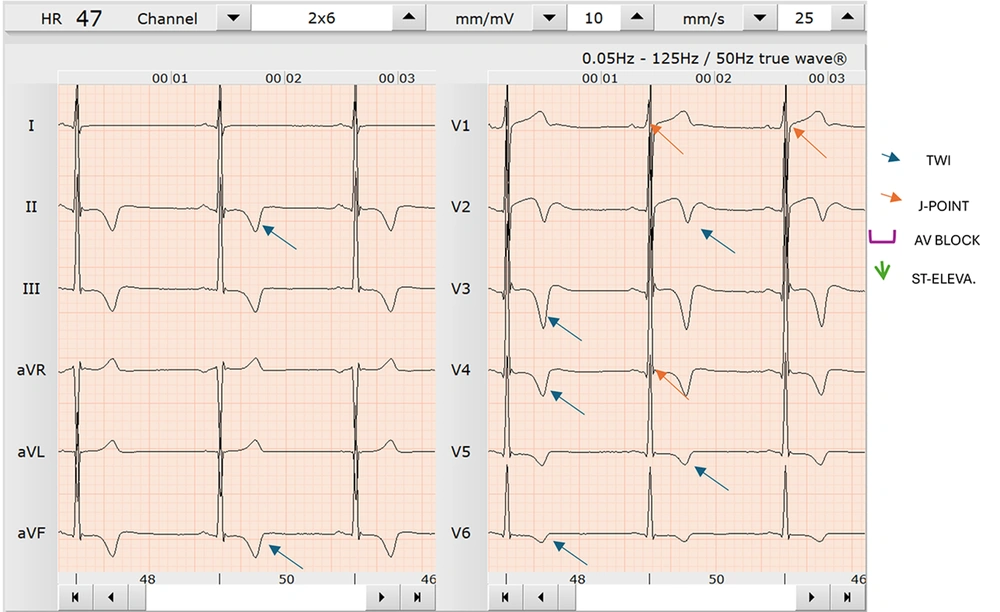

Athlete B is a 23-year-old South African male professional soccer player who presented for a preseason medical screening. He was part of the same cohort of 105 players recruited for a research study on the ECG profiles of black South African soccer players. Athlete B was asymptomatic at the time of screening. However, unlike the typical ECG changes associated with black athlete’s heart as classified by the ESC international consensus standards for ECG interpretation in black athletes, athlete B exhibited T-wave inversions limited to the anterior leads of V2-V3 (Figure 3). These changes may also be observed in endurance athletes due to exercise-induced cardiac remodeling and lateral displacement of the cardiac apex. These ECG findings, as shown in Figure 3, are consistent with a low risk profile and align with established research and the ESC international consensus standards. Additionally, athlete B also presented with a training-related first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, which is commonly observed in black athletes with ST-segment elevation in the inferior leads according to the ESC international consensus standards for ECG interpretation in athletes.

3. Discussion

Athlete’s heart is clinically defined by myocardial wall thickening and left ventricular enlargement observed during ECHO screening (3). These changes are common among athletes and may resemble patterns that clinically indicate underlying cardiovascular disease (CVD) (3).

Accurate interpretation of an athlete’s ECG is essential to differentiate physiological heart adaptations from pathological conditions with similar features (3). Misinterpretation may lead to false reassurance or unnecessary, costly examinations, potentially resulting in unwarranted disqualification from competitive sports or even SCD (3). Sudden cardiac death is defined as unexpected death due to cardiac causes occurring within one hour of symptom onset, or within 24 hours in unwitnessed cases, following an acute change in cardiovascular status in the absence of external causal factors (7). Sudden cardiac death is estimated to account for approximately 13% to 20% of all deaths (8). However, its epidemiology and etiology among athletes remain controversial, as some cases may go unreported or unrecognized (7). Recent epidemiologic data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in the United States suggest that SCD occurs at an incident rate of 1 per 44,000 athlete deaths per year, indicating a higher prevalence than previously estimated (9). Epidemiologic studies further indicate that risk factors for SCD vary by sport, sex, and race (10). The highest-risk sports for SCD, in descending order, are basketball, track, cross-country, football/soccer, and swimming (9).

The ESC international consensus standards categorize the physiological changes associated with athlete’s heart into two groups to assist clinicians in differentiating pathological findings from the common training-related physiological changes (8). Common and training-related ECG changes include sinus bradycardia, first-degree AV block, incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB), early repolarization, and isolated QRS voltage criteria for LVH. In contrast, uncommon and training-related ECG changes include ST-segment depression, T-wave inversions, pathological Q waves, left atrial enlargement, left axis deviation or left anterior hemiblock, right axis deviation or left posterior block, right ventricular hypertrophy, ventricular pre-excitation, complete left or RBBB, long or short QT interval, and Brugada-like early repolarization (8). In the general population, T-wave inversion is associated with cardiovascular risk factors and carries an increased risk of SCD (5). Among black African athletes, T-wave inversion is the most detectable ECG change observed in approximately one in every four screened athletes (11). This physiological remodeling significantly impacts the resting ECG of black African athletes, with T-wave inversions most notable in the anterior leads (V1-V4) rather than the lateral leads (5). Research indicates that T-wave inversions in the lateral leads among black African athletes are more likely to be associated with HCM than benign physiological changes of athlete’s heart (5). Such cardiac changes are consistent with patients who present with cardiomyopathy due to underlying cardiac complications, rather than with athletes competing in elite sport (5). The association between the type of sport and the occurrence of abnormal ECG findings in athletes is not well established. However, the ESC international consensus standards for ECG interpretation in athletes have improved over the last decade and are now regarded as the gold standard for classifying athlete’s heart (12).

Given the significant overlap between these pathological changes and normal black African variants, it can be challenging to rule out cardiomyopathy based on ECG alone. Consequently, athlete B would require further evaluation utilizing an ECHO. However, recent research has attempted to clarify some of these changes observed in athletes. In another study provided significant insights into ECG interpretation in athletes of black African descent. They reported that athletes with T-wave inversion combined with J-point elevation > 1 mm confined to the anterior leads V1-V4 should be excluded from a pathologic cardiomyopathy diagnosis. Their findings demonstrated that such changes can be excluded from pathological cardiomyopathy with 100% negative predictive value, regardless of ethnicity. This supports classifying case B’s ECG changes as common and training related.

Conversely, minimal or absent J-point elevation (< 1 mm) may reflect underlying pathological cardiomyopathy. In case A, ECG tracings showed J-point values were < 1 mm, as illustrated in Figure 4, which may indicate early signs of cardiomyopathy. This association underscores the need for comprehensive imaging to exclude coexisting cardiomyopathic anomalies in athletes with such presentations. J-point elevation < 1 mm in ECG tracings is a recognized marker of HCM, a cardiac abnormality associated with a high risk of SCD in athletes. In the absence of other conditions that would explain these findings, HCM is characterized by structural changes in the cardiac morphology, most notably LVH (13). In case A, LVH was confirmed by using the Sokolow-Lyon voltage criteria (14). This method assesses LVH potentials by calculating the sum of the R wave in lead V5 or V6 (whichever is larger) and the S wave in lead V1. A combined value exceeding 35 mm is indicative of LVH (15). In case A, the athlete’s combined measurement exceeded 38 mm, confirming the presence of LVH.

Unlike the common training-related changes observed in Case B, Case A presents a dilemma in management, especially in a resource-limited setting like South Africa, where ECHO facilities are restricted to hospital use and overflowing with patients with noncommunicable diseases. Given that athlete A reported only intermittent palpitations without other symptoms suggestive of heart failure, and considering the limited availability of ECHO facilities and specialized personnel, the decision to refer the athlete for further evaluation was made at the discretion of the team physician and management staff.

3.1. Conclusions

To develop practical and effective prevention strategies, it is essential that clinicians interpreting the ECGs of soccer players must understand the mechanisms underlying SCA or SCD in Black African athletes. The cases presented in this study highlight the importance of further evaluation for cardiomyopathy to distinguish between pathological conditions from typical athlete’s heart adaptations in black African athletes. Both athletes in this report exhibited T-wave inversions, which in the general population would be considered indicative of elevated cardiovascular risk or an increased likelihood of SCD. However, as seen in the two cases reported, clinicians must carefully assess the leads in which T-wave inversions occur, as well as the position of the J-point, to accurately determine the level of risk. Clinicians should also incorporate additional evaluations, such as ECHO, and need to be aware of the relatively high prevalence of T-wave inversion in black African athletes and familiarize themselves with the risk level classification outlined in the international consensus standards for ECG interpretation in athletes.

![The athlete during a Bruce protocol stress test (load 8.0 km and gradient of 16%); this focuses on the precordial leads with no sign of any T-wave inversion. This is the same athlete displayed in <a href="#A160337FIG1">Figure 1</a> [resting electrocardiogram (ECG)]. The athlete during a Bruce protocol stress test (load 8.0 km and gradient of 16%); this focuses on the precordial leads with no sign of any T-wave inversion. This is the same athlete displayed in <a href="#A160337FIG1">Figure 1</a> [resting electrocardiogram (ECG)].](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/40777e5fecb848da5010f402a8e69705e86db08f/asjsm-16-2-160337-g002-preview.webp)