1. Background

Exercise training induces varying degrees of mechanical and metabolic stress on the human body, resulting in inflammation and oxidative stress (1). Excessive inflammation can hinder recovery and performance (2). For this reason, there is increasing interest in finding nutritional supplements and foods with functional benefits to enhance metabolic capacity, reduce the effects of oxidative stress, delay the onset of fatigue, improve muscle hypertrophy, shorten the recovery period, and, in other words, boost athletic performance in athletes (3, 4). The International Society of Sports Nutrition lists fish as one of the best sources of high-quality protein for athletes because it provides ample fuel and helps build and repair muscle (5). Fish provides a variety of nutrients, including protein, essential fats, and vitamins and minerals such as calcium, magnesium, selenium, zinc, iron, and vitamins A and D (6). The health benefits of fish are primarily attributed to their content of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 LCPUFA) or omega-3 (7). Important features of fish oil and omega-3 include antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (modulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and eicosanoids), immune-modulatory effects (8-11), enhancement of lipid metabolism (12-14), and glucose metabolism (15), as well as changes in cell membrane permeability (16). Fish compounds can improve endothelial function and increase blood flow, delivering more nutrients and oxygen to the muscles, enhancing endurance, and reducing fatigue (17). These properties have led athletes to use fish oil supplements as ergogenic aids in recent years. In studies by Jouris et al. and Philpott et al. and, it was found that fish oil reduces muscle damage and soreness caused by exercise (2, 18). In a study by Jeromson et al., ω-3 PUFA supplementation reduced protein breakdown in cancerous rodents (11). On the other hand, some studies have found that fish oil does not impact athletic performance (19). D’Angelo et al. stated that only limited scientific evidence proves that fish oil supplementation positively affects sport performance. Therefore, at present, it cannot be concluded that fish oil is consistently effective or energizing (3). Further studies are necessary.

Another feature of fish consumption is its potential effect on improving lipid profiles and enhancing fat metabolism. According to study results, compounds found in fish may influence the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism. Omega-3 fatty acids can activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), which play an important role in regulating lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis (20). This activation can lead to increased fatty acid oxidation and improved athletic performance. However, the effect of fish consumption on lipid profiles is inconsistent. Several studies have shown that fish consumption or supplements lower triglycerides (3, 21), reduce LDL (21), and increase HDL (22). In some studies, LDL (22) and HDL (23) levels did not change; therefore, further investigation is necessary.

Vitamin D is an essential micronutrient for enhancing health and athletic performance. The main sources of vitamin D are dietary sources and exposure to sunlight. Among vitamin D-rich foods, oily fish are considered to be one of the best sources (24). A systematic study reported that consuming at least two servings of fish, or 300 grams of fish per week, over a period of at least four weeks, was associated with a significant increase in serum 25-hydroxy D concentrations (25). According to estimates, one billion people worldwide, with more than half of them in Iran, are deficient in vitamin D (26). A high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency has been documented among athletes in both outdoor and indoor sports (27). One characteristic of vitamin D is its impact on musculoskeletal health, cardiovascular health, and immune system function (28). Also, in observational and interventional studies, insufficient vitamin D levels were associated with adverse serum lipid profiles (29-31), which reduced exercise performance. Research has shown that high serum levels of vitamin D are associated with reduced injury rates and improved athletic performance. It is recommended that individuals with vitamin D deficiency be identified and take supplements to optimize their performance and prevent future complications (32). Consuming fresh rainbow trout is an excellent way to boost your vitamin D levels. That’s because a 3-ounce (85-gram) serving of rainbow trout contains 645 international units of vitamin D. In fact, rainbow trout is one of the fish that are high in vitamin D (6).

Given the valuable properties of fish, it is essential to consider potential barriers to fish consumption among athletes. Factors such as taste preferences and concerns about sustainability and mercury exposure may limit fish consumption among some individuals. Wild fish tend to have higher mercury levels due to contaminants, while farmed fish are generally in a better position. On the other hand, due to increased fish consumption, aquaculture has risen, reducing the burden on wild fish stocks (33). Although most studies suggest that wild fish have higher levels of omega-3 and vitamin D than farmed fish (34, 35), the high mercury content of wild fish reduces their consumption. There is also controversy regarding the effects of fish on exercise performance, lipid profiles, and vitamin D3.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the effect of increasing fish consumption (4 to 5 servings per week) on the aforementioned variables and, if it affects the variables, to determine whether farmed trout is as effective as wild trout.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects and Study Procedure

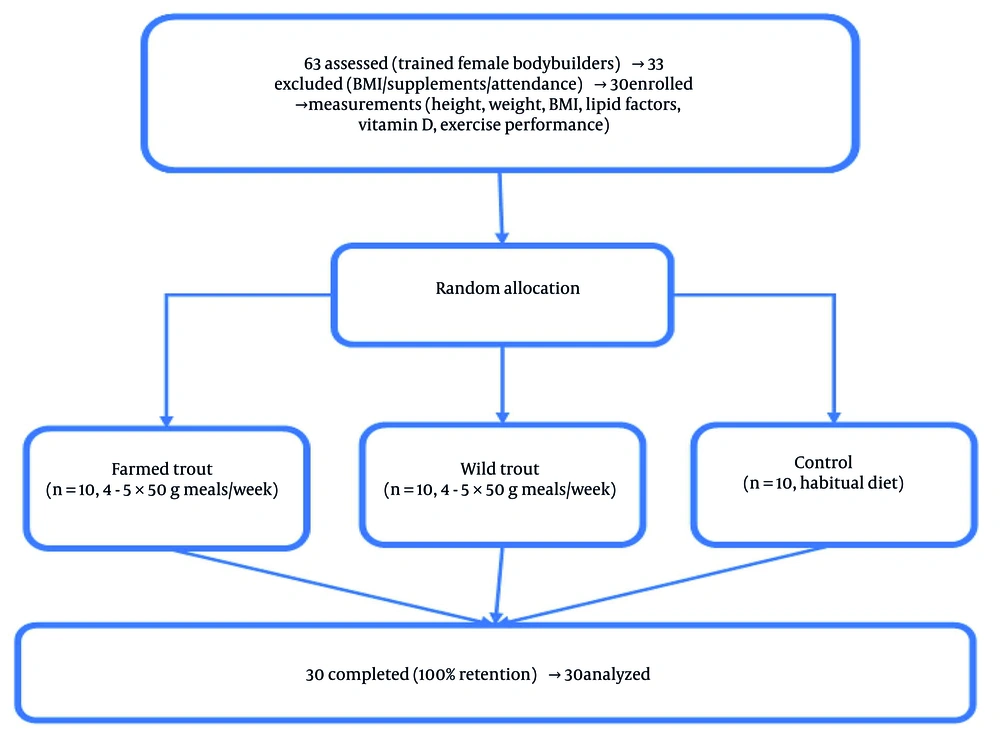

This study employed a quasi-experimental design with pre-test and post-test assessments, comprising three parallel groups: Two intervention groups (wild trout and farmed trout consumers) and one control group. Participants were non-randomly selected via convenience sampling from female bodybuilders training at Apadana Club in Rasht, Iran, but random allocation to groups was performed after recruitment to minimize bias. The statistical population consisted of female bodybuilders aged 20 to 30 years with ≥ 6 months of regular training history at Apadana Club. From 63 initial volunteers, 30 eligible participants were selected after screening based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Sample size was determined using G*Power 3.1 software (α = 0.05, power = 80%, medium effect size).

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

Female gender, age 20 to 30 years, minimum 6 months of regular bodybuilding training, Body Mass Index (BMI) 18.5 - 25 kg/m2, absence of chronic diseases (cardiovascular, diabetes, hypertension, etc.), no use of dietary supplements (especially vitamin D and omega-3/6 fatty acids), non-smoker and non-alcohol consumer, similar physical fitness [assessed through the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) and researcher-developed demographic/training history questionnaire], and informed consent.

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

Missing > 3 training sessions during the study, sustaining exercise-related injuries, consuming < 2 fish meals/week (for intervention groups).

To calculate BMI, height and weight were first measured. The subjects’ height was measured without shoes using a wall-mounted stadiometer (0.1 cm precision). Their weight was measured with a digital scale while wearing minimal clothing (Seka, 0.1 kg precision). The BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. Exercise performance, lipid profile, and vitamin D (using blood sampling) were also measured.

After initial measurements, participants were randomly divided into three groups via a random number table: (1) Farmed trout group (n = 10, 4 - 5 farmed trout meals/week), (2) wild trout group (n = 10, 4 - 5 wild trout meals/week), (3) control group (n = 10, maintained habitual diet without fish). All three groups followed the same bodybuilding regimens. Given the nature of the dietary interventions in this study, blinding of participants and trainers was not feasible. However, several strategies were implemented to minimize potential bias: Outcome assessors (including laboratory technicians conducting biochemical analyses) remained blinded to group allocation throughout the study period, all measurements were performed using standardized protocols, and random assignment to study groups was conducted only after participant recruitment and baseline assessments. After grouping, the intervention variable was applied for four weeks. Figure 1 shows the participant flow chart.

In the present study, all ethical considerations were observed. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Voluntary participation and the right to withdraw were emphasized. Confidentiality of participant information was guaranteed, and approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee.

3.4. Measuring Research Variables

3.4.1. Measuring Athletic Performance

To measure maximum upper and lower body strength (1 repetition maximum), the chest press movement (36) and the leg press movement (37) were utilized, respectively. One repetition maximum is the maximum weight that a muscle or muscle group can lift at one time, calculated and estimated using the following formula. To prevent injury, several repetitions between four and eight were utilized to estimate one-repetition maximum (1RM). The test was stopped when the number of repetitions of the weight lifted was between 4 and 8. The number of repetitions and the weight lifted were then input into the formula below to calculate the maximum repetitions.

In this study, the average anaerobic power was calculated using the RAST test. After warming up, the subject ran a distance of 35 meters at maximum speed on the handlebars. At the end of the distance, the athlete rested for 10 seconds. Immediately after the 10-second rest, the athlete ran the distance again at maximum speed. The athlete ran the distance at maximum speed six times. Records were taken at each stage. The six-step record was converted to anaerobic power using the formula "anaerobic power = weight × 1225 ÷ time3". To calculate the average anaerobic power, the average of the six power records was taken (the sum of the six anaerobic power values divided by six) (38).

3.4.2. Lipid Profile and 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 Measurement

Blood sampling was performed 48 hours before the start of training and 48 hours after the last training session in a fasting state of 10 to 12 hours. Before each blood sampling session, the subjects rested for a few minutes in a sitting position. Then, in the shortest possible time, 10 cc of blood was drawn from the cubital vein of their left elbow between 8 and 9 a.m. by a laboratory technician. After blood collection, the blood samples were placed at room temperature for 20 minutes to allow for clotting. The tubes containing the samples were then centrifuged for 10 minutes at a speed of 3000 - 3500 rpm (Rontgen Company device, made in Germany). The separated serum was transferred into special microtubes and stored at -20°C. Vitamin D analysis and determination were conducted using a commercial kit from Pars Peyvand Company, with intra-group and inter-group coefficients of less than 11% and 12%, respectively. The lipid profile, including total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, and LDL, was measured using an enzymatic method with a biochemical autoanalyzer and a Pars Azmoun kit at Alzahra Laboratory in Rasht. The error rate for all intergroup and intragroup assessments was under 1%.

3.5. Intervention

3.5.1. Exercise Protocol

Subjects in all three groups continued their activities, which included bodybuilding exercises three times a week, with each session lasting 60 minutes. After a 10-minute warm-up, the subjects performed the main exercise. After the main exercise, a 5-minute cool-down was performed. All training sessions were conducted under the supervision of a specialized trainer at Apadana Club (39).

3.5.2. Fish Consumption and Monitoring Protocol

This study provided farmed and wild trout (800 - 1000 g) to participants in the intervention groups. To ensure precise dietary control, participants were instructed to consume 50 g of fish per serving, totaling 4 - 5 servings per week for 4 weeks, exclusively during lunchtime meals. This portion size was selected based on practical feasibility and compliance considerations, while still delivering a biologically relevant dose of n-3 fatty acids and vitamin D3 (25). The use of fish oil supplements was prohibited across all groups to isolate the effects of whole-fish consumption. The fatty acid and vitamin D3 content of trout were derived from published literature, as direct laboratory analysis was not feasible. Wild trout contained 6.82% EPA, 8.97% DHA (DHA/EPA ratio: 1.31), with total n-3 (∑n3) and n-6 (∑n6) fatty acids at 25.75% and 8.37%, respectively (40). Farmed trout exhibited distinct profiles: 1.86% EPA, 9.91% DHA (DHA/EPA ratio: 5.32), lower n-3 (15.79%), but higher n-6 (34.01%) (40). For vitamin D3, wild and farmed trout values were estimated at 1.10 μg/g and 1.12 μg/g, respectively (41). A qualified nutritionist supervised dietary adherence, with participants maintaining daily food diaries to record fish intake. No allergic reactions, gastrointestinal disturbances, or adverse events were reported, and all participants completed the study without withdrawals. The control group adhered to a fish-free diet under identical monitoring.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

In this study, all descriptive data were presented as means and standard deviations. After examining the normality of the data distribution with the Shapiro-Wilk test and confirming it, the ANCOVA test was employed to analyze the differences between groups. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS statistical software version 26 at a significance level of P < 0.05.

4. Results

Table 1 shows the individual characteristics of the subjects before the interventions. The average age, height, weight, and BMI of all subjects were 24.63 ± 1.93 years, 167.53 ± 3.83 cm, 68.10 ± 4.04 kg, and 24.26 ± 1.19 kg/m2, respectively. By performing a one-way ANOVA test, no significant differences were observed between the study groups in all baseline measurements, including age, weight, height, and BMI (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

| Movements and Exercise Intensity | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leg press | ||||

| Set × rep | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 |

| %1RM | 40 - 50 | 50 - 60 | 60 - 70 | 70 |

| Lying leg curl | ||||

| Set × rep | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 |

| %1RM | 40 - 50 | 50 - 60 | 60 - 70 | 70 |

| Standing biceps cable curl | ||||

| Set × rep | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 4 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 |

| %1RM | 40 - 50 | 50 - 60 | 60 - 70 | 70 |

| Triceps rope pushdown | ||||

| Set × rep | 3 × 8 - 12 | 4 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 |

| %1RM | 40 - 50 | 50 - 60 | 60 - 70 | 70 |

| Chest press | ||||

| Set × rep | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 |

| %1RM | 40 - 50 | 50 - 60 | 60 - 70 | 70 |

| Machine seated crunch | ||||

| Set × rep | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 |

| %1RM | 40 - 50 | 50 - 60 | 60 - 70 | 70 |

| Squats | ||||

| Set × rep | 4 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 |

| %1RM | 40 - 50 | 50 - 60 | 60 - 70 | 70 |

| Toe raises | ||||

| Set × rep | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 | 3 × 8 - 12 |

| %1RM | 40 - 50 | 50 - 60 | 60 - 70 | 70 |

| Variables | Control (n = 10) | Wild Trout (n = 10) | Farmed Trout (n = 10) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 24.90 ± 2.18 | 24.8 ± 1.68 | 24.2 ± 2.04 | 0.782 |

| Height (cm) | 166.7 ± 3.46 | 168.2 ± 3.96 | 167.7 ± 4.27 | 0.687 |

| Weight (kg) | 67.4 ± 3.83 | 69.3 ± 3.86 | 67.6 ± 4.55 | 0.530 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 24.25 ± 0.77 | 24.5 ± 1.13 | 24.05 ± 1.60 | 0.713 |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

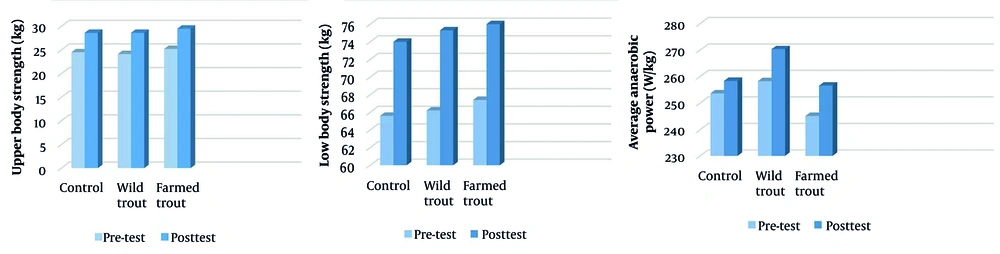

The results of the covariance test showed no significant difference between the three groups in the indices of upper body muscle strength (P = 0.37, F = 1.02, η2 = 0.07), lower body muscle strength (P = 0.53, F = 0.64, η2 = 0.04), and mean anaerobic power (P = 0.57, F = 0.56, η2 = 0.04) (Table 3). The sports performance graph is shown in Figure 2.

| Variables and Steps | Control | Wild Trout | Farmed Trout | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper body strength (kg) | 1.023 | 0.374 | 0.073 | |||

| Pre-test | 24.5 ± 2.90 | 24.1 ± 2.87 | 25.2 ± 2.99 | |||

| Post-test | 28.6 ± 2.21 | 28.6 ± 2.17 | 29.5 ± 2.22 | |||

| Lower body strength (kg) | 0.648 | 0.531 | 0.048 | |||

| Pre-test | 65.6 ± 5.25 | 66.2 ± 5.43 | 67.4 ± 5.42 | |||

| Post-test | 74 ± 4.94 | 75.3 ± 5.18 | 76 ± 4.54 | |||

| Average anaerobic power (W/kg) | 0.569 | 0.573 | 0.042 | |||

| Pre-test | 253.6 ± 33.72 | 258.2 ± 31.73 | 245.1 ± 38.56 | |||

| Post-test | 258.3 ± 33.81 | 270.3 ± 29.23 | 256.5 ± 36.09 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

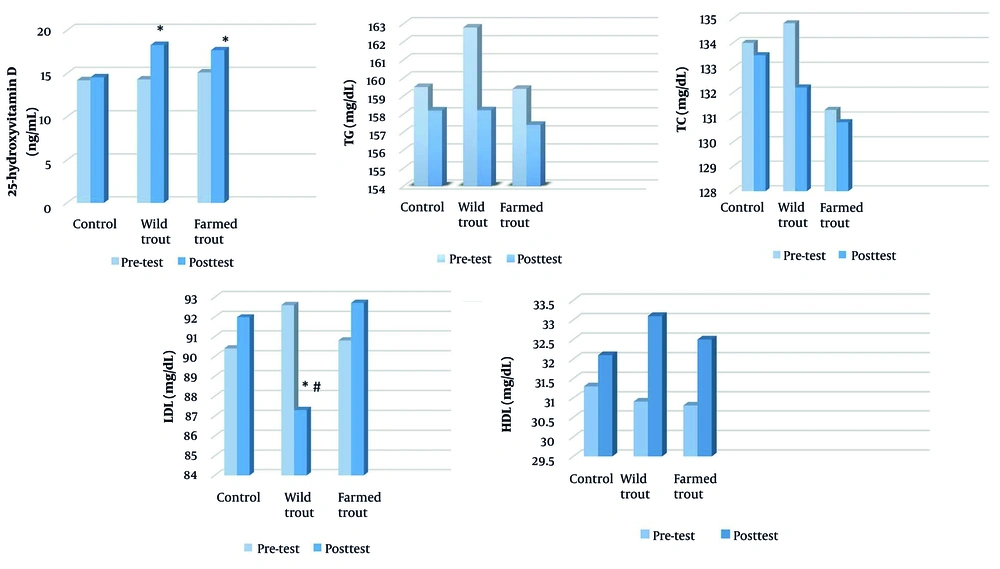

According to the results of the analysis of covariance, significant differences were observed in the variables of vitamin D and LDL among the three groups (P = 0.000). However, no significant differences were observed in the variables of triglycerides (P = 0.15), total cholesterol (P = 0.48), and HDL (P = 0.05) among the three groups (Table 4).

| Variables and Steps | Control | Wild Trout | Farmed Trout | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D (ng/mL) | 43.431 | 0.000 b | 0.770 | |||

| Pre-test | 14.2 ± 1.53 | 14.3 ± 1.18 | 15.1 ± 1.13 | |||

| Post-test | 14.25 ± 1.96 | 18.10 ± 1.10 | 18.20 ± 1.39 | |||

| TG (mg/dL) | 2.026 | 0.152 | 0.135 | |||

| Pre-test | 159.5 ± 15.06 | 162.8 ± 15.21 | 159.4 ± 14.86 | |||

| Post-test | 158.20 ± 15.48 | 158.21 ± 14.98 | 157.40 ± 15.28 | |||

| TC (mg/dL) | 0.743 | 0.485 | 0.054 | |||

| Pre-test | 134 ± 10.94 | 134.8 ± 13.07 | 131.3 ± 11.64 | |||

| Post-test | 133.5 ± 11.8 | 132.2 ± 11.56 | 130.8 ± 11.92 | |||

| HDL (mg/dL) | 3.169 | 0.059 | 0.196 | |||

| Pre-test | 31.3 ± 4.05 | 30.9 ± 6.25 | 30.8 ± 4.85 | |||

| Post-test | 32.10 ± 4.06 | 33.10 ± 5.97 | 32.5 ± 4.30 | |||

| LDL (mg/dL) | 18.174 | 0.000 b | 0.583 | |||

| Pre-test | 90.4 ± 10.6 | 92.6 ± 11.56 | 90.8 ± 8.86 | |||

| Post-test | 91.97 ± 0.68 | 87.30 ± 0.69 | 92.71 ± 0.65 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Statistical significance between groups.

The Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons demonstrated that both wild and farmed trout consumption significantly increased vitamin D levels compared to the control group [wild trout: +3.76 ng/mL, P < 0.000, 95% CI (2.66, 4.86); farmed trout: +3.15 ng/mL, P < 0.000, 95% CI (2.02, 4.30)], with no significant difference observed between the two trout groups [mean difference = 0.60 ng/mL, P = 0.554, 95% CI (-0.53, 1.73)]. For LDL cholesterol levels, wild trout showed significantly greater reductions compared to both farmed trout [-5.41 mg/dL, P < 0.000, 95% CI (-7.89, -2.92)] and control [-4.67 mg/dL, P < 0.000, 95% CI (-7.15, -2.18)], while farmed trout did not significantly differ from control [mean difference = 0.74 mg/dL, P = 1.000, 95% CI (-1.74, 3.22)] (Figure 2). These results indicate that while both trout types were equally effective at increasing vitamin D levels, only wild trout consumption led to significant LDL cholesterol reduction, suggesting potential differences in their bioactive compound profiles that warrant further investigation (Figure 3).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effects of consuming 50 grams of farmed and wild trout four to five times per week on exercise performance, lipid profiles, and vitamin D levels. Consuming four servings of farmed and wild trout did not affect upper and lower body muscle strength or anaerobic capacity in female bodybuilders. Studies examining the effects of fish consumption and its main components on athletic performance have been conducted in various populations, and the results of these studies have been somewhat inconsistent. A similar study reported in a review that fish oil consumption had no effect on endurance performance, muscle strength, or exercise adaptation (42). Lee et al. reported that omega-3 supplementation at 1.2 g of eicosapentaenoic acid and 0.72 g of docosahexaenoic acid per day for 12 weeks did not improve muscle strength and physical performance induced by resistance training, which is consistent with the findings of the current study (43). One study demonstrated that 18 weeks of omega-3 supplementation (3 × 1 g capsules daily, providing 2.1 g EPA/d + 0.6 g DHA/d) significantly improved muscle performance and quality (strength per unit muscle area) in older women undergoing resistance training. However, this effect was not observed in male participants (44). Smith et al. also noted that six months of omega-3 supplementation, without an exercise intervention, resulted in significant increases in grip strength (45). Mamerow et al. acknowledged that the anti-inflammatory properties of omega-3 supplements can affect muscle repair and growth, as well as increase muscle protein synthesis (46). In another study, Krzyminska-Siemaszko et al. reported improvements in body mass and muscle strength in elderly individuals after 12 weeks of omega-3 supplementation (47), which were inconsistent with the findings of the current study.

The lack of observed effect of fish consumption on exercise performance in the present study may be attributed to multiple factors. The relatively short study duration (4 weeks) likely played a significant role, as most comparable studies demonstrating positive effects employed intervention periods of 12 weeks or longer (44, 45, 47). Physiological adaptations to nutritional interventions — particularly for strength and anaerobic capacity — typically require ≥ 8 to 12 weeks to manifest (48). Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory properties of omega-3 fatty acids and their potential to enhance muscle protein synthesis may require extended exposure periods to yield measurable performance improvements (46). The dosage of fish consumption (200 - 250 g/week) in our study was notably lower than the 300 g/week used in similar research (25). It should also be considered that most existing studies examining exercise performance effects have focused on concentrated fish components (e.g., fish oil or isolated omega-3 supplements) rather than whole fish consumption, typically over longer intervention periods (2, 3, 11, 18, 20). Demographic variables including age, sex, baseline nutritional status, and fish species/source may further influence study results. An important consideration is that our participants’ regular exercise habits and presumably adequate baseline nutrition may have minimized any additional benefits from fish consumption, as their nutritional status was likely already optimized for performance.

In this study, LDL levels remained unchanged in the farmed trout group but significantly decreased in the wild trout group compared to the control and farmed trout groups. No significant differences were found in other lipid parameters among the groups. Previous research on fish consumption’s effects on lipid profiles has shown inconsistent results across different populations. Erkkila et al. found that low-fat fish consumption (≥ 4 times per week) for 8 weeks had no significant effect on triglyceride, cholesterol, or HDL levels, which is consistent with our findings (13). Wang et al. demonstrated that omega-3 intake led to a linear reduction in triglycerides and LDL (49). In contrast, Dadash Nejad et al. reported metabolic improvements after eight weeks of combined training and omega-3 supplementation, contradicting our result (50). Similarly, Fakhrzadeh et al. observed that fish oil supplementation (1 g/day for 6 months) effectively lowered triglycerides in elderly subjects, a finding inconsistent with our study (51). These inconsistencies may be attributed to variations in intervention duration, dosage, exercise regimens, demographic characteristics, or participants’ health status. The beneficial effects of physical activity on lipid profiles are mediated through multiple mechanisms including reduced fat mass, enhanced lipolysis, increased oxygen consumption, improved glucose uptake (via GLUT-4 activation), and various muscular adaptations (52, 53). Similarly, fish consumption may positively influence lipid metabolism by modulating gene expression related to fat metabolism (20). However, the lack of change in lipid profile in the present study could be related to the short duration of the study. In some studies, fish consumption for 8 weeks or more has improved lipid profiles (50, 51). Changes in lipid metabolism often require sustained dietary changes (13, 49). On the other hand, the participants’ baseline normal lipid levels may also have limited the extent of improvement.

This study found that both wild and farmed trout consumption significantly increased 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels compared to the control group, though no significant difference was observed between the two fish groups. Limited studies have examined the effects of consuming different types of fish on vitamin D levels. Lehmann et al. observed a significant increase in vitamin D concentrations in the group consuming farmed rainbow trout in a review study, which is consistent with the present study (25). Eslick et al. reported that consuming fatty and lean fish at least four times a week had no effect on vitamin D levels, which is inconsistent with the present study (54). In a study conducted in autumn in southwestern Norway at latitude 60°N, it was reported that five 75-gram servings of salmon per week for dinner were inadequate to prevent a decrease in serum vitamin D in overweight adults (49). When analyzing vitamin D3 levels, it is important to consider that these levels can vary according to the season, geographic location, ethnicity, training environment, type of sport, and diverse populations (55). The Australian Nutrition Society recommends consuming fatty fish to optimize vitamin D levels (56). The increase in vitamin D in both fish consumption groups in the present study may be related to the high number of servings consumed. Unfortunately, at the start of the study, all subjects had lower than normal levels of vitamin D. Although fish consumption increased their vitamin D levels, they still remained below normal levels. The lack of difference in fish consumption between the two groups could be related to the duration of the study. In the wild trout group, vitamin D increased more, which was not significant compared to the farmed fish group, although it might have been significant if the study duration had been extended. As stated in previous studies, wild fish have higher levels of vitamin D (34). Despite the effect of vitamin D on improving athletic performance and lipid profile, this study found that its increase, along with the anti-inflammatory properties of fish, failed to cause any change in athletic performance and lipid profile, which can be attributed to the short duration of the study.

5.1. Conclusions

The results of the study indicate that the consumption of farmed and wild trout had no effect on sport performance (upper body strength, lower body strength, and average anaerobic power), total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL levels in trained female bodybuilders. However, consuming both types of fish increased vitamin D levels in the subjects. On the other hand, LDL levels were significantly reduced in the group consuming wild trout compared to both the control group and the group consuming farmed trout. It is recommended that individuals with vitamin D deficiency consume fish. Additionally, further research should be conducted on the impact of fish consumption on athletic performance.

5.2. Limitations

This study had several limitations. The small sample size may reduce the generalizability of the findings, and the short 4-week intervention period might have been insufficient to detect significant changes in performance and lipid profiles, as longer durations (≥ 8 - 12 weeks) are typically needed for measurable effects. The dosage of fish consumed (200 - 250 g/week) was relatively low compared to other studies, and participants’ pre-existing athletic lifestyles and optimized diets may have limited additional benefits. Dietary intake outside the intervention was not strictly controlled, and the study focused solely on female bodybuilders, limiting applicability to other populations. Seasonal variations in vitamin D levels and natural differences in fish nutrient composition were not accounted for. Additionally, the lack of muscle biopsies or molecular analyses prevented deeper mechanistic insights. Future studies should explore longer interventions, larger and more diverse cohorts, and direct comparisons between whole fish and isolated omega-3 supplements.