1. Background

Cheerleading expresses cheerfulness and beauty through special jumps, dance, tumbling, and stunts that are performed as assembly gymnastics. In competition, stunts are scored higher than tumbling and dance, and the overall difficulty and speed of the routine are scored separately. Therefore, stunts with high difficulty and speed attract high scores but can also be expected to cause injuries.

The number of injuries sustained by cheerleaders in the United States more than doubled between 1990 and 2002 (1). Between 1982 and 2001, female high school and collegiate athletes in the United States sustained 75 direct and 36 indirect fatalities or catastrophic injuries (2, 3). Of these 75 athletes, 50 were high school athletes and 25 were college athletes. Among the 50 high school athletes injured, 25 were cheerleaders (50%), 9 were gymnasts (18%), 4 were track and field athletes (8%), and the remainder were spread over six other sports. In a study that compared injuries sustained in 23 sports, cheerleaders had the 18th highest injury incidence rate but the second highest incidence of suspensions or medical disqualifications of three weeks or more due to injury (4). They concluded that although the frequency of injuries in cheerleaders is low, their impact is likely to be serious.

Several studies have reported the incidence of cheerleading injuries as well as the injury location, type of injury, injury situation (competition or practice), and maneuver attempted at the time of injury (2, 5). A few studies on cheerleaders have reported injury severity overall and for each body part (4, 5). The majority of such studies, however, have assessed only the incidence of injury, without reporting their severity. Therefore, it is currently unknown which injuries should be prioritized for prevention.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence and severity of injuries among high school cheerleaders in Japan and to assess the associated durations of absence.

3. Methods

3.1. Population

Enrolled in this prospective study were 74 female high school cheerleaders. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Cheerleaders between the ages of 15 and 17 years who were observable over 6 months, (2) members of a team affiliated with the Chubu Cheerleading Regional Federation of Japan Cheerleading Association, and (3) in a team that participated in the 2018 Japan CUP Cheerleading Championship. The Japan CUP is the national championship, and qualification requires placement within the top 40% of teams in regional competitions. All teams included in this study had participated in this championship, indicating a high-performing cohort. The three participating schools were selected via convenience sampling, based on their agreement to cooperate with the research protocol. The exclusion criteria were cheerleaders whose previously sustained injuries prevented their participation in club activities at the beginning of the study period. The observation period was the 6 months between September 1, 2019, and February 29, 2020, which included the high school championships in January and the Japan CUP Cheerleading championships in February, corresponding to the in-season period for competitive high school cheerleading (Table 1). As the study involved minors, written informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians, and written assent was obtained from all participants. The study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Chukyo University (Approval No. 2019-068).

| Variables | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| No. | 64 |

| Height (m) | 1.57 ± 0.05 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.3 ± 4.9 |

| BMI | 20.4 ± 2.0 |

| Age (y) | 15.8 ± 0.6 |

| Competition history in cheerleading (y) | 1.8 ± 2.0 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; BMI, Body Mass Index.

3.2. Questionnaire

Questionnaires were used to obtain participants’ age, high school grade, and current and previous medical history. Body weight was assessed using a body composition analyzer (InBody 470; InBody Japan, Tokyo, Japan). An onsite survey of all participants was conducted by interview once a month regarding the number of days of activity, presence of injury, injury type, injury location, maneuver attempted at the time of injury, and dates of injury and return to play.

3.3. Definitions

Definitions of athlete-exposures (AEs) and injuries were based on previous studies (5, 6). An AE was defined as a single cheerleader taking part in one cheerleading activity. Cheerleading activities included all cheerleading practices, pep rallies, athletic events, and competitions. An athletic event was characterized as a sports event where cheerleading teams performed, such as a football or basketball game. Exposure was calculated from information obtained by asking advisors or coaches at each club about the schedule of activities and the attendance of cheerleaders. Injury incidence was defined as the number of injuries per 1,000 AEs, based on previous studies (5, 6).

A reportable injury was defined as one meeting all three of the following requirements: (1) It resulted from participation in a structured cheerleading practice, pep rally, sporting event, or cheerleading competition, (2) it prevented the affected cheerleader from continuing involvement in that practice, pep rally, sporting event, or competition, or caused a prolonged absence, and (3) it necessitated the cheerleader to obtain medical care.

Medical care was defined as satisfying all four of the following conditions: (1) Care administered either at the scene or in a healthcare facility, (2) treatment provided either immediately or within two weeks following the injury occurrence, (3) intervention required due to the sustained injury, and (4) care delivered by a licensed athletic trainer, physical therapist, nurse, or doctor. Full recovery was defined as the athlete’s return to full participation in practices, pep rallies, athletic events, and competitions. Recovery status was determined by a physician, physiotherapist, or athletic trainer.

Injury type was classified in accordance with the IOC classification criteria (7). Duration of absence was defined as the number of days required to return to play, based on previous studies (5, 6). The number of days of absence was defined as the days that the cheerleader did not participate in any practices or competitions in cheerleading. In accordance with the 2020 IOC consensus statement (8), injury severity was classified as no time-loss (0 days), minor (1 - 7 days), moderate (8 - 28 days), or severe )> 28 days).

3.4. Data Collection

The researcher was in contact with the physical therapist accompanying the team each time an injury occurred and visited each high school once a month to interview all cheerleaders based on a self-questionnaire about injury and record results. Injury interviews and assessments were consistently conducted by the same skilled physical therapist with 15 years of clinical experience and nine years as a cheerleading trainer. The physical therapist confirmed the physical findings based on questionnaires and interviews.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The study results enabled the calculation of statistical power. Data analysis was performed using EZR software (Version 1.35) (9). The injury incidence rate was determined as the number of injuries per 1,000 AEs, as in previous studies (4, 5), and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for the incidence of injury according to injury location, injury type, duration of absence, and maneuver attempted at the time of injury. Injury burden was calculated as the total number of days lost due to injuries within each category (e.g., body location, injury type), expressed per 1,000 AEs (8).

4. Results

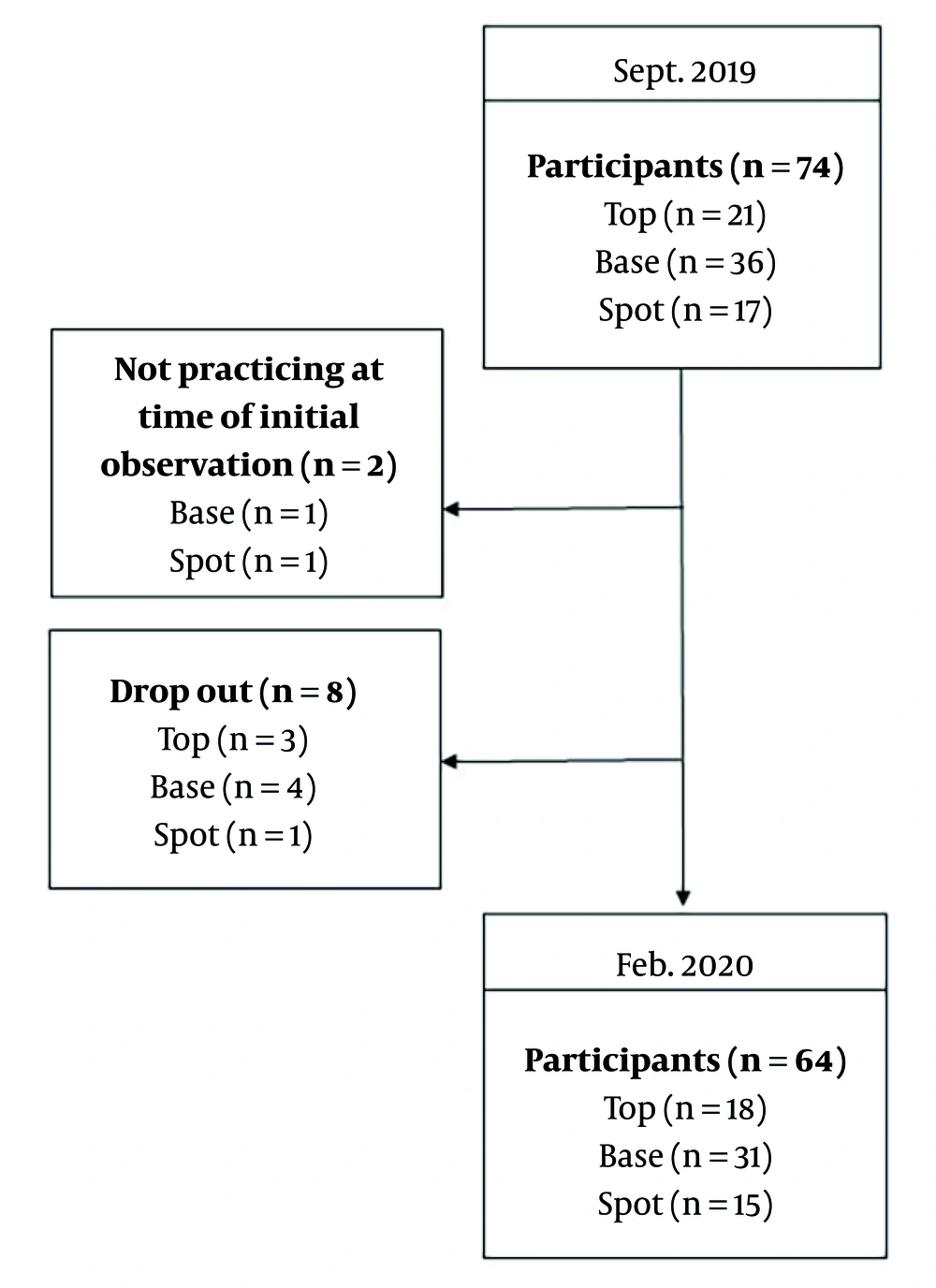

Over the 6-month study period, 64 of the 74 cheerleaders were observed (Figure 1). Of the 10 excluded cheerleaders, 2 were not participating in practice at the start of observation due to injury, and 8 quit the club during the study period. During the observation period, 29 injuries were reported in 8,025 AEs, resulting in an overall incidence rate of 3.61/1,000 AEs (95% CI: 2.30 - 4.93).

The most commonly injured body areas were the head and knee (0.62/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 0.08 - 1.17), followed by the wrist (0.50/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 0.01 - 0.99, Table 2). Joint sprain (1.37/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 0.56 - 2.18) was the most common injury pathology, followed by brain/spinal cord injury and cartilage injury (each 0.50/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 0.01 - 0.99, Table 3).

| Body Region/Area | No. (%) | Injuries per 1000 AEs (95% CI) | Median Time Loss Days (Min - Max) | Time Loss Days per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | ||||

| Head | 5 (17.2) | 0.62 (0.08 - 1.17) | 7 (1 - 30) | 5.98 (4.29 - 7.67) |

| Neck | 1 (3.4) | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) | 7 | 0.87 (0.23 - 1.52) |

| Upper limb | ||||

| Shoulder | 2 (6.9) | 0.25 (0.00 - 0.59) | 30.5 (1 - 60) | 7.60 (5.70 - 9.50) |

| Elbow | 3 (10.3) | 0.37 (0.00 - 0.80) | 90 (30 - 150) | 33.64 (29.70 - 37.59) |

| Wrist | 4 (13.8) | 0.50 (0.01 - 0.99) | 30 (3 - 35) | 12.21 (9.81 - 14.61) |

| Hand | 2 (6.9) | 0.25 (0.00 - 0.59) | 2 (1 - 3) | 0.50 (0.01 - 0.99) |

| Trunk | ||||

| Thoracic spine | 1 (3.4) | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) | 12 | 1.50 (0.65 - 2.34) |

| Lumbosacral | 1 (3.4) | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) | 1 | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) |

| Lower limb | ||||

| Knee | 5 (17.2) | 0.62 (0.08 - 1.17) | 21 (7 - 210) | 57.32 (52.23 - 62.41) |

| Lower leg | 2 (6.9) | 0.25 (0.00 - 0.37) | 23.5 (17 - 30) | 5.86 (4.19 - 7.53) |

| Ankle | 3 (10.3) | 0.37 (0.00 - 0.80) | 25 (1 - 34) | 7.48 (5.59 - 9.36) |

| Total | 29 (100) | 3.61 (2.30 - 4.93) | 17 (1 - 210) | 133.08 (125.65 - 140.52) |

Abbreviations: AEs, athlete-exposures; CI, confidence interval.

| Tissue/Pathology | No. (%) | Injuries per 1000 AEs (95% CI) | Median Time Loss Days (Min - Max) | Time Loss Days per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle/tendon | ||||

| Muscle injury | 2 (6.9) | 0.25 (0.00 - 0.59) | 4 (1 - 7) | 1.00 (0.31 - 1.69) |

| Muscle contusion | 1 (3.4) | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) | 17 | 2.12 (1.11 - 3.12) |

| Nervous | ||||

| Brain/spinal cord injury | 4 (13.8) | 0.50 (0.01 - 0.99) | 7 (1 - 30) | 5.61 (3.97 - 7.24) |

| Bone | ||||

| Fracture | 2 (6.9) | 0.25 (0.00 - 0.59) | 18.5 (3 - 34) | 4.61 (3.13 - 6.09) |

| Bone stress injury | 1 (3.4) | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) | 30 | 3.74 (2.40 - 5.07) |

| Bone contusion | 3 (10.3) | 0.37 (0.00 - 0.80) | 12 (7 - 12) | 3.86 (2.51 - 5.22) |

| Synovitis/capsulitis | 1 (3.4) | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) | 1 | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) |

| Ligament/joint capsule | ||||

| Joint sprain (ligament tear or acute instability episode) | 11 (37.9) | 1.37 (0.56-2.18) | 30 (1 - 210) | 94.45 (88.06 - 100.85) |

| Cartilage/synovium/bursa | ||||

| Cartilage injury | 4 (13.8) | 0.50 (0.01 - 0.99) | 30 (21 - 60) | 17.57 (14.70 - 20.44) |

| Total | 29 (100) | 3.61 (2.30 - 4.93) | 17 (1 - 210) | 133.08 (125.65 - 140.52) |

Abbreviations: AEs, athlete-exposures; CI, confidence interval.

The body areas associated with the most time loss were the elbow (90 days, 95% CI: 30 - 150), followed by the shoulder (30.5 days, 95% CI: 1 - 60, Table 2). Bone stress injury (30 days, 95% CI: 30 - 30), joint sprain (30 days, 95% CI: 3 - 150), and cartilage injury (30 days, 95% CI: 25.5 - 45) were the injury pathologies with the most time loss (Table 3).

The highest injury burden by body area was observed for the knee (57.32/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 52.23 - 62.41), followed by the elbow (33.64/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 29.70 - 37.59, Table 2). The knee was the most affected body region in terms of injury burden. Regarding injury pathology, joint sprains were the primary contributor to this burden, followed by cartilage injuries.

Most time-loss injuries resulted in an absence of > 28 days (n = 12, 41.4%, 1.50/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 0.65 - 2.34, Table 4). Within this duration of absence, the most common injury locations were the elbow and wrist (each n = 3, 25.0%), the type of injury was joint sprain (n = 6, 50.0%), and the maneuver attempted at the time of injury was a stunt (n = 7, 58.3%). Two injuries resulted in a duration of absence of > 6 months, both of which were anterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee. The most common maneuver attempted at the time of injury was a stunt (23/29, 79.3%, 2.87/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 1.70 - 4.04), followed by tumbling (3/29, 10.3%, 0.37/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 0.00 - 0.59, Table 5). By maneuver, the highest number of injuries occurred during stunts (n = 23, 79.3%). Among the stunts, the highest incidence (1.50/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 0.65 - 2.34) was observed at a height of 2 layer 2 1/2 high, followed by 3 layer 2 1/2 high and basket toss (0.62/1,000 AEs, 95% CI: 0.08 - 1.17, Table 6).

| Severity (d) | No. (%) | Absence per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 (17.2) | 0.62 (0.08 - 1.17) |

| 1 to 7 | 7 (24.2) | 0.87 (0.23 - 1.52) |

| 8 to 28 | 5 (17.2) | 0.62 (0.07 - 1.17) |

| > 28 | 12 (41.4) | 1.50 (0.65 - 2.34) |

| Total | 29 (100) | 3.61 (2.30 - 4.93) |

Abbreviations: AEs, athlete-exposures; CI, confidence interval.

| Maneuver | No. (%) | Injuries per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Stunt | 23 (79.3) | 2.87 (1.70 - 4.04) |

| Tumbling | 3 (10.3) | 0.37 (0.00 - 0.80) |

| Jump | 1 (3.4) | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) |

| Training | 2 (6.9) | 0.25 (0.00 - 0.59) |

| Total | 29 (100) | 3.61 (2.30 - 4.93) |

Abbreviations: AEs, athlete-exposures; CI, confidence interval.

| Stunt | No. (%) | Injuries per 1000 AEs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 layer 2 1/2 high | 5 (21.7) | 0.62 (0.08 - 1.17) |

| 2 layer 2 1/2 high | 12 (52.2) | 1.50 (0.65 - 2.34) |

| 2 layer | 1 (4.3) | 0.12 (0.00 - 0.37) |

| Basket toss | 5 (21.7) | 0.62 (0.08 - 1.17) |

| Total | 23 (100) | 2.87 (1.70 - 4.04) |

Abbreviations: AEs, athlete-exposures; CI, confidence interval.

5. Discussion

This prospective study was conducted to investigate the incidence of injuries and days of absence in high school cheerleaders in Japan over a period of 6 months. Twenty-nine injuries were reported in 8,025 AEs during this period, with an overall incidence rate of 3.61/1,000 AEs (95% CI: 2.30 - 4.93). The head and knee were the most commonly injured body areas, and joint sprain was the most common type of injury. The majority of time-loss injuries resulted in an absence of > 28 days. The most common maneuver attempted at the time of injury was a stunt.

The injury rate was 3.61/1,000 AEs during the observation period. In contrast, a study of cheerleaders in the USA reported an injury rate of 2.4/1,000 AEs (5). This rate is also considerably higher than the 0.71/1,000 AEs reported in the large-scale U.S. study by Currie et al. (4). The difference in injury rates may be attributed to the fact that the previous study included teams regardless of their participation in national competitions, whereas all teams in the present study competed at the national level. Several previous studies have reported that injuries occur more frequently at higher levels of competition (10, 11), presumably because the higher the technical level of the athlete, the greater the mechanical load he or she is subjected to during competition. Additionally, athletes at higher skill levels may perform with greater intensity and aggression compared to those at lower skill levels, potentially increasing their risk of injury. The injury rates reported by the National Federation of State High School Associations for other sports, including women's soccer (2.46/1,000 AEs) and women's gymnastics (1.81/1,000 AEs), were lower than those observed in the present study (4).

The head and knee were the most commonly injured body areas in our study (each 17.2%), followed by the wrist (13.8%). This finding contrasts with reports from the U.S., where Currie et al. (4) reported the head/face (38.5%) and ankle (11.7%) as the most frequent sites. Schulz et al. (12) reported the ankle as the most common location (23.6%), followed by the knee (10.7%) and head (8%), and Jacobson et al. (2) reported the ankle as the most frequent location (44.9%), followed by the wrist (19.3%) and knee (11.9%). The consistent finding of high ankle injury rates in U.S. studies, compared to the high rate of knee injuries in our study, may reflect differences in regulations or common techniques between the two countries. For example, different rules regarding stunt complexity could alter the load on the lower extremities of bases and spotters, leading to different injury patterns. The most common type of knee injury in the present study was joint sprain, the same as in previous studies (5). All of the present head injuries occurred while performing a stunt, two on the top and two on the base: When the top fell while executing the stunt and conversely as the base caught the top. The present knee injuries occurred in a variety of situations, including jumping, tumbling, and catching a stunt, and most occurred during landings. It has been reported that gender is a risk factor for knee injuries and that the landing motion is the most common injury mechanism (13, 14). These two factors are also characteristic of competitive cheerleading. All wrist injuries occurred during stunts, and all were in the base position. The incidence of wrist injury was highest in a particular stunt maneuver in which the base supports the top with their palms (partner stunt: Two layer, 2.5 tiers), thus overloading the wrist joint of the base. In addition, a previous study found that cheerleading maneuvers that involve intensive use of the wrist joint cause significant stress to the deltoid fibrocartilage complex and can lead to severe injuries (15).

Regarding injury pathology, the most common was joint sprain (37.9%), followed by brain and spinal cord injury, and cartilage injury (each 17.2%). In previous studies, joint sprain (53%) was the most common injury pathology, followed by contusions and hematomas (13%) (5). Sprain and ligament injuries are also common in gymnastics (which, along with cheerleading, is an aesthetic sport), and the incidence of knee ligament injuries has been reported to differ by gender (males 0.12/1,000 h, females 0.24/1,000 h) (16, 17). Reasons for the difference may include static and dynamic alignment, joint laxity, and landing movements specific to females (18-21).

The most common time-loss injuries according to body area were those of the elbow (medial collateral ligament injury and dislocation, n = 3), followed by those of the shoulder (labral injury and bursitis, n = 2). Regarding injury pathology, joint sprains (n = 11), cartilage injury (n = 4), and bone stress injury (n = 1) were the most common time-loss injuries. The distribution of joint sprains was relatively even, with three cases involving the elbow and two each involving the knee, wrist, ankle, and hand.

The knee had the greatest overall burden, based on time loss and injury rate, followed by the elbow. No previous studies in cheerleading have quantified burden in this manner. However, the knee has been reported as the most common body area for surgery requiring time to return to play (4). In this study, the knee was also the most common injury requiring surgery. The reason for the knee having the greatest burden may be related to the high incidence of injury and the high number of injuries requiring surgery. Regarding burden by injury pathology, joint sprain was the most common. This is probably because 11 of the 29 (37.9%) injuries were joint sprains, and these injuries had the highest time-loss in the study.

The majority of time-loss injuries resulted in a duration of absence of > 28 days (41.4%). Schultz et al. (12) reported that a duration of 1 to 3 weeks was the most common (22.6%). Of the present injuries that resulted in an absence of > 28 days, the most common locations were the wrist and elbow (each n = 3, 25%), followed by the knee (n = 2, 16.7%); the type of injury was joint sprain (n = 6, 50%), and the maneuver attempted was a stunt (n = 7, 58.3%). These results may be attributable to the high incidence of injuries resulting in > 28 days of absence, as well as the high frequency of wrist, elbow, and knee joint sprains sustained during stunt attempts. Among the maneuvers attempted, stunts accounted for the largest proportion of injuries (79.3%) and had the highest incidence rate (2.87/1,000 AEs; 95% CI: 1.70 - 4.04). Several previous studies have also reported that stunts were the most common maneuver attempted at the time of injury, with rates exceeding 50% (2, 4, 5). A potential explanation for the higher prevalence of injuries in stunts is the presence of dual injury mechanisms. As multi-person maneuvers, stunts are susceptible to both contact and non-contact injuries. In contrast, solo maneuvers are primarily exposed to only non-contact mechanisms. This distinction is reflected in our findings: Of the 23 stunt-related injuries observed in this study, 12 were classified as contact and 11 as non-contact. Injury incidence by height of stunt was the highest for 2 layer 2 1/2 high, despite not being the highest layer stunt. Therefore, it is necessary to recognize that factors other than height influence the occurrence of injuries in stunts. Three potential factors can be considered. First, at the top, most stunts at 2 layer 2 1/2 high are performed on one leg, whereas most at 3 layer 2 1/2 high are performed on both legs. As the base of support and thus stability is higher with both legs than with only one leg, injuries occur more frequently in performances with one leg, as has been reported in a previous study of stunt injuries (6). Second, at 2 layer 2 1/2 high, the flyer is supported by the palms and joints of the hands, whereas the upper body and upper limbs are used at 3 layer 2 1/2 high. We speculate that this difference gives the flyer more stable balance at the greater height. Accordingly, we hypothesize that at 2 layer 2 1/2 high, maneuvers on the smaller and more fragile support surface increase the physical load on the bases, due to the trauma caused by falling and the high instability of the performance. Third, at 2 layer 2 1/2 high, the top can fall in multiple directions, but at 3 layer 2 1/2 high, its direction of fall is primarily directed backward. Based on this, we suggest that there is a greater possibility of missed catches and resulting falls to the ground at 2 layer 2 1/2 high than at 3 layer 2 1/2 high, which may have led to the higher frequency of injuries at the lower height. Future research with biomechanical analysis is needed to validate these hypotheses.

This study has some limitations. First, the small sample size (64 athletes from three high schools) limits the generalizability of our findings to all Japanese high school cheerleaders. Future large-scale studies are needed to establish more comprehensive national data. Second, the IOC consensus statement published in 2020 recommends various surveillance durations, such as tournament, season, whole year, or playing career (8). In contrast, the observation period of this study was confined to the competitive in-season, thereby excluding the post-season, which constitutes a limitation. Third, exposure was measured in AEs rather than hours. Although consistent with prior foundational research in this field, it is a limitation given that current consensus favors time-based rates for better comparability. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted with caution when compared to studies that use a per-1,000-hour denominator.

5.1. Conclusions

The injury incidence rate among high school cheerleaders in Japan was 3.61/1,000 AEs. The head and knee were the most commonly injured body areas, and joint sprain was the most common injury pathology. The majority of time-loss injuries resulted in an absence of > 28 days. There were two injuries with a duration of absence > 6 months, all of which were knee ligament injuries. Stunt was the most common maneuver associated with injury, accounting for 79.3% of all reported injuries. Among stunt injuries, 52.2% occurred at 2 layer 2 1/2 high. These findings suggest that in addition to height, the factors of stability and direction of fall also influence the incidence of stunt injuries; and indicate that in terms of injury location and number of days absent, knee sprains should be prioritized for prevention.