1. Background

COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has emerged as a global public health crisis, profoundly impacting healthcare systems worldwide. This disease has not only led to a significant rise in the number of hospitalizations but has also introduced new challenges in managing and caring for these patients. Reinfection and readmission rates are vital indicators of pandemic control and healthcare system performance. Variants of SARS-CoV-2 have been identified globally, leading to increased reinfection rates and subsequent hospital readmissions. Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) reports, the readmission rate for COVID-19 patients is significantly higher than for other diseases, necessitating a comprehensive investigation into the causes and contributing factors of readmission (1-3). Reported readmission rates for COVID-19 patients are varied, with some studies indicating levels between 1% and nearly 50%. Additionally, follow-up data on discharged COVID-19 patients have revealed a post-discharge mortality rate up to one year after the initial hospitalization (4, 5).

Literature review reveals numerous studies examining the factors associated with readmission in COVID-19 patients. Specifically, patients with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases are more likely to experience readmission. An effective care system and post-discharge follow-up can significantly reduce the rate of readmission. However, gaps in the current knowledge still exist, necessitating further in-depth studies (6, 7).

According to WHO reports, 10% to 20% of COVID-19 patients require readmission after their initial discharge. Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of Ramzi (8), COVID-19 patients had a 10.34% readmission rate within one year, with most readmissions occurring within the first 30 days post-discharge (8.97%), and developed countries showed higher readmission rates (10.68%) than developing countries (6.88%). Also, the one-year post-discharge all-cause mortality was 7.87%, again with the highest mortality within the first 30 days (7.87%). Mortality was particularly higher in patients with underlying conditions and in older populations (8). Higher readmission and mortality rates are associated with older age, underlying health conditions, and country-specific factors like healthcare access. In some studies, the readmission rate has been reported to be as high as 45%. For instance, a study in the United States indicated that 14.5% of COVID-19 patients were readmitted within 60 days of their initial discharge (9-11). These statistics highlight the importance of thoroughly investigating the factors associated with readmission and developing effective strategies to prevent it.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the 60-day readmission rate in COVID-19 patients at hospitals affiliated with Abadan University of Medical Sciences. Hospital readmission is often viewed as an indicator of suboptimal healthcare quality and ineffective disease management, with serious implications for patient safety. Consequently, questions such as "What factors contribute to the increased readmission rate among COVID-19 patients?" and "What clinical and laboratory features can serve as predictors for readmission?" arise. As such, this research seeks to identify the timing and causes of readmission, as well as the clinical and laboratory predictors associated with the readmission rate. Identifying these factors can not only improve treatment processes and reduce complications associated with readmission but also serve as a tool for assessing the quality of healthcare services and enhancing patient safety. This information can lead to the development of effective strategies for managing patients and improving healthcare quality (12-14).

By providing more accurate predictive models and identifying contributing factors, it is possible to improve care quality and reduce the financial burden caused by readmissions. These results can assist healthcare policymakers and decision-makers in designing more effective strategies for managing the disease and mitigating its associated complications.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the 60-day hospital readmission rate among COVID-19 patients in a single Iranian teaching hospital and to identify independent clinical and laboratory predictors of readmission. By establishing a risk profile, the study aimed to inform post-discharge strategies that can reduce preventable readmissions, improve patient safety, and enhance healthcare quality.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population and Sampling Method

The study focused on COVID-19 patients admitted to a hospital between March 21, 2020, and March 20, 2023. The study was conducted under the ethics committee of Abadan University of Medical Sciences (IR.ABADANUMS.REC.1401.103). From a total of 7,182 admissions, 121 patients were readmitted within 60 days after discharge. These readmitted patients were matched with 121 non-readmitted controls based on demographic and clinical similarities. A total of 242 patients (121 readmitted and 121 non-readmitted) were analyzed.

Matching criteria: Demographic factors: Age (± 5 years), gender (exact match); clinical characteristics: Comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease), disease severity (initial SPO₂ ± 2%, ICU admission requirement).

A propensity score matching technique was used to minimize selection bias and control for confounding variables. Nearest-neighbor matching with a caliper width of 0.2 standard deviations ensured high-quality matches. Standardized mean differences (< 0.1) were used to assess the quality of matching.

Inclusion criteria: Confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19; hospital admission between March 21, 2020, and March 20, 2023; readmitted patients: At least one night's stay within 60 days post-discharge; non-readmitted patients: Similar demographic and clinical characteristics as readmitted patients

Exclusion criteria: Incomplete or inconsistent laboratory data; patients not admitted during the designated study period.

3.2. Data Collection

Data were extracted from the Hospital Information System (HIS) and included: Demographic information: Age, gender; admission details: Admission date; underlying conditions: Comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension); laboratory findings: Data included respiratory markers (SPO₂, respiratory rate, ventilation requirement), liver function tests [ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total and direct bilirubin], renal markers [blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine], inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR), cardiac biomarkers (troponin, CK-MB), hematologic markers (hemoglobin, WBC, platelet count), and electrolytes (sodium, potassium). These values were recorded at initial admission and compared between readmitted and non-readmitted groups.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics: Mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage were calculated for continuous and categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were conducted using: Independent t-tests: For continuous variables (e.g., age, laboratory parameters); chi-square tests/Fisher's exact test: For categorical variables (e.g., gender, comorbidities); Multivariate logistic regression modeling was performed to evaluate the simultaneous effect of multiple variables on readmission. This approach identified independent predictors of readmission while controlling for potential confounders. This structured methodology ensured robust analysis and minimized bias, providing reliable insights into readmission patterns and associated risk factors among COVID-19 patients.

4. Results

This study investigated readmission patterns and associated factors in 7,182 COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital between March 2020 and March 2023. A total of 121 readmitted patients were matched with 121 non-readmitted controls based on demographic and clinical characteristics. The findings are presented below, supported by detailed tables to enhance clarity and interpretation.

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

The study included 242 participants (121 readmitted and 121 non-readmitted). The mean age of the participants was 50.66 ± 15.95 years, ranging from 18 to 88 years. Gender distribution was relatively balanced, with 52.1% male and 47.9% female participants. Table 1 shows demographic features in both study groups, including mean age, gender distribution, and statistical comparisons.

| Variables and Groups | Number (%) | Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Readmission; age (y) | 54.9 ± 16.721 | ||

| Male | 63 (52.10) | 0.009 | |

| Female | 58 (47.90) | 0.031 | |

| Single admission; age (y) | 46.85 ± 14.531 | ||

| Male | 63 (52.10) | ||

| Female | 58 (47.90) | ||

| Total | 242 | - | - |

4.2. Overview of Readmission Patterns and Key Contributing Factors

The overall readmission rate within 60 days post-discharge was 1.68% (121 out of 7,182 patients), significantly lower than international rates reported in prior studies. The mean time to readmission was 6.42 ± 6.244, indicating that most readmissions occurred relatively soon after discharge. This underscores the importance of early post-discharge monitoring. Notably, the duration of initial hospitalization was longer compared to subsequent hospitalizations, as detailed in Table 2. This difference in hospital stay duration between the readmitted group (mean = 6.42 days) and the single-admission group (mean = 5.08 days) highlights variations in care needs and recovery trajectories among these groups (P = 0.114) (Table 2).

| Variable and Group | Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital stays (d) | 0.114 | |

| Readmission | 6.42 ± 6.244 | |

| Single admission | 5.08 ± 1.816 |

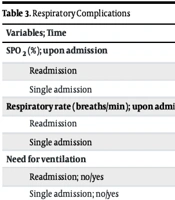

Respiratory complications emerged as the leading cause of readmission, accounting for 30.6% of cases. These complications were marked by significantly lower SPO₂ levels and higher respiratory rates among readmitted patients, as shown in Table 3. Additionally, mechanical ventilation was required for 26 readmitted patients compared to only 4 in the non-readmitted group (P < 0.00001), emphasizing the severity of respiratory dysfunction in this population. Beyond respiratory issues, other notable findings included elevated bilirubin levels indicating liver dysfunction, increased BUN levels reflecting renal impairment, and multi-organ involvement contributing to readmissions. Mortality was also significantly higher in the readmission group (P ≈ 0.013), further highlighting the complexity of managing high-risk patients (Table 3).

| Variables; Time | Number | Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPO2 (%); upon admission | 0.004 | ||

| Readmission | 121 | 89.56 ± 7.89 | |

| Single admission | 121 | 93.72 ± 5.908 | |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min); upon admission | 0.002 | ||

| Readmission | 121 | 22.26 ± 2.578 | |

| Single admission | 121 | 20.92 ± 1.536 | |

| Need for ventilation | < 0.00001 | ||

| Readmission; no/yes | 95/26 | - | |

| Single admission; no/yes | 117/4 | - |

4.3. Liver and Renal Function Tests

To further investigate organ-specific dysfunction, we analyzed liver and renal function parameters in both study groups. Notably, significant differences were observed in ALP and direct bilirubin levels, with total bilirubin emerging as an independent predictor of readmission in multivariate analysis. Similarly, BUN levels were significantly higher in readmitted patients, reflecting renal impairment. These findings are summarized in Table 4, which provides a comprehensive comparison of liver and renal function tests between the two groups.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| ALP (U/L) | 0.024 | |

| Readmission | 191.89 ± 83.292 | |

| Single admission | 216.47 ± 85.673 | |

| Total Bilirubin (U/L) | 0.071 | |

| Readmission | 0.6 ± 0.358 | |

| Single admission | 0.69 ± 0.413 | |

| Direct Bilirubin (U/L) | 0.011 | |

| Readmission | 0.25 ± 0.174 | |

| Single admission | 0.32 ± 0.249 | |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 0.005 | |

| Readmission | 22.68 ±13.391 | |

| Single admission | 15.67 ± 11.106 |

Abbreviation: BUN, blood urea nitrogen.

4.4. Multivariate Analysis of Readmission Predictors

Six independent predictors of readmission were identified through multivariate logistic regression analysis: Advanced age, male gender, lower SPO₂ at admission, elevated potassium, increased BUN, and higher total bilirubin. These predictors provide a robust framework for understanding readmission risk factors and highlight the importance of targeted interventions for high-risk patients. Table 5 summarizes the final multivariate logistic regression model, including odds ratios and confidence intervals for each predictor.

| Variables | Regression Coefficient | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.031 | 1.031 | 1.009 - 1.054 |

| Gender (male) | 0.693 | 2 | 1.183 - 3.381 |

| SPO2 | -0.021 | 0.979 | 0.959 - 0.999 |

| Potassium | 0.115 | 1.122 | 1.031 - 1.221 |

| BUN | 0.019 | 1.019 | 1.004 - 1.035 |

| Total bilirubin | 0.135 | 1.145 | 1.034 - 1.267 |

Abbreviation: BUN, blood urea nitrogen.

4.5. Statistical Considerations and Limitations

All variables in the final model were statistically significant, with 95% confidence intervals excluding 1. The predictive strength of the identified factors, in descending order, was as follows: Male gender > total bilirubin > potassium > age > SPO₂ > BUN. However, the single-center design of the study introduces limitations, including potential selection bias and residual confounding. Despite these constraints, the results provide valuable insights into readmission risk factors and emphasize the need for targeted interventions.

The low readmission rate of 1.68% observed in this study contrasts sharply with international rates (10 - 45%), warranting further investigation into local practices that may contribute to this outcome. The identified predictors — advanced age, male gender, lower SPO₂, elevated potassium, increased BUN, and higher total bilirubin — align with existing literature and underscore the multifactorial nature of readmission risk. Respiratory complications were the leading cause of readmission (30.6%), followed by hepatic (19.8%) and renal dysfunction (12.4%), indicating multi-organ involvement. These findings highlight the importance of systematic post-discharge monitoring, particularly for high-risk groups, to reduce readmission rates and improve long-term patient outcomes.

This study identifies six independent predictors of COVID-19 readmission and emphasizes the need for targeted post-discharge interventions. The observed readmission rate of 1.68% is significantly lower than global averages, suggesting the potential transferability of best practices. Future multi-center studies are essential to validate these findings and assess intervention effectiveness across diverse healthcare settings.

5. Discussion

This study identified an exceptionally low 60-day COVID-19 readmission rate (1.68%) at a single Iranian teaching hospital, which is substantially below the global range of 10 - 45% reported in systematic reviews and large-scale cohorts (8, 9). For example, Ramzi reported a pooled one-year readmission rate of 10.34%, with most readmissions occurring within the first 30 days (8). Similarly, U.S. studies documented 14 - 20% 60-day readmissions (9, 15), while European cohorts reported rates exceeding 12% (16, 17). Our markedly lower rate raises questions about local practices that may be protective, including longer initial hospital stays, more conservative discharge thresholds, or structured post-discharge monitoring. These findings highlight the importance of evaluating institutional strategies for potential transferability to other healthcare systems.

Multivariate analysis revealed six independent predictors of readmission: Advanced age, male sex, lower SPO₂ at admission, elevated potassium, increased BUN, and higher total bilirubin. These results align with international evidence linking hypoxemia, renal dysfunction, and hepatic involvement to poor outcomes. A U.S. cohort study demonstrated that patients with admission hypoxemia had a 40% higher likelihood of readmission (17). Elevated BUN, reflecting renal impairment, has been consistently associated with increased COVID-19 mortality and rehospitalization risk (18), while hyperbilirubinemia may indicate viral or inflammatory hepatic injury, both of which complicate recovery. Male sex, which doubled the odds of readmission in our study, is a well-established predictor of severe COVID-19 outcomes, possibly due to differences in ACE2 receptor expression, immune modulation, and comorbidity profiles (9, 19).

Interestingly, pre-existing comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease were not significant predictors in our cohort after matching. This contrasts with prior meta-analyses where comorbidities increased readmission risk by up to 34% (8, 16). This discrepancy may be explained by the study design — propensity score matching minimized comorbidity imbalance between groups — and by effective local disease management protocols, such as structured outpatient follow-up for chronic conditions.

Our data also underscore the multi-system nature of COVID-19 readmissions. Respiratory complications remained the most common cause (30.6%), but hepatic (19.8%) and renal dysfunction (12.4%) also contributed substantially. These findings mirror international reports indicating that COVID-19 is not only a respiratory illness but a multi-organ disease requiring integrated follow-up strategies (17, 18). Systematic monitoring of renal and hepatic function during the post-discharge period may prevent avoidable readmissions.

The remarkably low readmission rate at our center warrants further exploration. Potential explanations include extended index admissions, rigorous inpatient stabilization, early rehabilitation referrals, and the use of standardized discharge criteria. Prospective multi-center studies are needed to validate these hypotheses and to test whether structured interventions — such as telemedicine-based multi-organ surveillance or risk-stratified discharge protocols — can reproduce similarly low rates in other regions (20).

Limitations include the single-center design, retrospective data collection, and the exclusion of patients with incomplete laboratory results. These factors may restrict generalizability to broader populations or to regions with different SARS-CoV-2 variants and health system structures. Nevertheless, our study contributes novel evidence by integrating demographic, clinical, and biochemical predictors into a unified readmission risk profile.

In summary, this study highlights a unique institutional outcome — an exceptionally low COVID-19 readmission rate — and identifies a robust set of predictors that can inform post-discharge care. Future research should focus on developing and validating risk scoring systems, evaluating discharge protocols across diverse healthcare contexts, and investigating mechanistic pathways linking biochemical abnormalities to post-COVID organ dysfunction. Such evidence-based strategies are essential to reduce readmission burdens and improve long-term patient outcomes.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that COVID-19 readmissions are strongly influenced by demographic, respiratory, renal, and hepatic factors, underscoring the need for multi-system vigilance after discharge. The exceptionally low readmission rate observed at our center suggests that local practices in discharge planning and follow-up may hold valuable lessons for broader healthcare systems. Moving forward, risk-stratified discharge protocols, structured post-discharge surveillance, and validation of institutional strategies across diverse settings will be essential for reducing preventable readmissions and strengthening post-COVID care.