1. Background

Mutations in genes that control cell growth and the cell cycle are associated with uncontrolled cell proliferation, which is referred to as cancer (1). Gastric cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide and is the most common gastrointestinal malignancy (2). Unfortunately, most patients with gastric cancer are diagnosed at advanced stages of the disease, which is associated with reduced treatment effectiveness (3). Treatment approaches include chemotherapy and surgery, both of which are associated with high side effects and the risk of recurrence (4). The efficacy of the drugs used decreases over time due to the development of drug resistance in cancer cells; therefore, improving the chemosensitivity of cancer cells is one of the important research goals in the treatment of gastric cancer (5, 6).

Doxorubicin (Dox) is a chemotherapeutic drug belonging to the anthracycline class, which is one of the most effective drugs in the treatment of a wide range of malignancies (7). It is used alone or in combination with other drugs to treat neoplasms, and its efficacy has been confirmed in various research studies (8). The Dox is able to induce cytotoxic effects by inducing apoptosis in tumor cells; however, cancer cells develop resistance to Dox over time, which is associated with reduced efficacy and treatment failure (9). Molecular mechanisms of the development of Dox resistance in cancer cells include the upregulation of multi-drug resistance transporters and proteins such as P-glycoprotein (10). In addition, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (ETM) is also involved in the development of Dox resistance and metastasis (11). It seems that finding drugs that can improve chemosensitivity in malignant tumors is important for improving the efficacy of treatment.

Resveratrol (RSV) is a natural polyphenol extracted from various plant sources, especially grapes. The RSV exhibits a wide range of pharmacological activities, such as antioxidant (12), anti-inflammatory (13), antidiabetic (12), hepatoprotective (14), cardioprotective (15), and anticancer (16) effects. Interestingly, this natural compound can not only prevent cancer with its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (17) but also improve the sensitivity of various cancer cells to Dox, thereby enhancing the efficacy of the treatment (18). For example, Kim et al. suggested that the combination of Dox and RSV in the treatment of breast cancer could be considered a strategy to improve the efficacy of the treatment of this malignancy, and it was found that RSV could enhance the intracellular accumulation of Dox (18), thereby improving the chemosensitivity of cancer cells. Interestingly, another study found that RSV improved the chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells to cisplatin by reversing macrophage polarization (19). In addition, RSV has been shown to improve chemosensitivity in other cancers, such as malignant mesothelioma (20), cholangiocarcinoma (21), and renal carcinoma (22). Therefore, it seems that RSV has a special place in improving the efficacy of chemotherapy in the treatment of various types of cancer, including gastric cancer.

2. Objectives

The current study aimed to investigate the impacts of RSV on the chemosensitivity of the gastric cancer cell line (AGS) treated with Dox. It is worth noting that the most widely used cell model in gastric cancer research is the AGS cell line, which is of great importance in studies related to tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis, especially in evaluating drug effects and developing new therapeutic approaches for gastric cancer (23-25). For this reason, this gastric cancer cellular model was used in the present study.

3. Methods

3.1. Cell Preparation and Culture

The AGS was obtained from the Pasteur Institute of Iran and immediately cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 5% FBS (reduced-serum medium) and antibiotics, and incubated at 5% CO2 and 37°C. The cells were passaged every 7 days, and growth was maintained in the logarithmic phase.

3.2. Cell Viability

The MTT assay was used to measure cell viability. In this assay, the reduction of MTT by the succinate dehydrogenase enzyme causes a color change from yellow to purple formazan crystals, and the number of viable cells is directly proportional to the color intensity. First, the cell suspension was poured into each well of a 96-well plate at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/mL and incubated for 24 hours. In the next step, the cells were treated with 0, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 µg/mL of RSV (Sigma, USA) and 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, and 10 µM Dox (Sigma, USA) at 24, 48, and 72 hours (n = 3). Then, 10 μL of MTT stock (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for 4 hours. After removing the MTT solution, 50 μL of DMSO was added to each well, and after 15 minutes, the absorbance of the samples was read at a wavelength of 570 nm using an ELISA reader.

3.3. Gene Expressions

Total cellular RNA was extracted after 48 hours of exposure to RSV and Dox using a kit (RiboEX, South Korea). RNA purity was measured using a NanoDrop device, and its quality was assessed using agarose gel. Then, a cDNA synthesis kit (Yekta Tajhiz Azma, Iran) was used to prepare cDNAs. Primer design was performed using Primer 3 software, and sequence accuracy was assessed in the NCBI database. Primer sequences of the studied genes are provided in Table 1.

| Genes | Forward (5'-3') | Reverse (5'-3') |

|---|---|---|

| p53 | CCTCAGCATCTTATCCGAGTGG | TGGATGGTGGTACAGTCAGAGC |

| Bcl-x | GGAAGCGAATCAATGGACTCTGG | GCATCGACATCTGTACCAGACC |

| MDR1 | CCCATCATTGCAATAGCAGG | GTTCAAACTTCTGCTCCTGA |

| MRP1 | ATCA AGACCGCTGTCATTGG | TCTCGTTCCTACTGAACGTC |

| MRP2 | ACAGAGGCTGGTGGCAACC | ACCATTACCTTGTCACTGTC |

| ANXA1 | GCGAAACAATGCACAGCGTCAAC | CAACCTCCTCAAGGTGACCTGT |

| TXN | GTAGTTGACTTCTCAGCCACGTG | CTGACAGTCATCCACATCTACTTC |

| GAPDH | GTGAACCATGAGAAGTATGACAAC | CATGAGTCCTTCCACGATACC |

The temperature-time program of the qRT-PCR device consisted of 1 cycle at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 seconds, 65 - 62°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds. We used the GAPDH gene as the control housekeeping gene, and all gene expression data were normalized based on this gene.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The gene expression data were analyzed using the 2-ΔΔCT method, and the cell viability data were analyzed using the ANOVA procedure at a significance level of P < 0.05, employing Tukey’s multiple range test for mean comparisons.

4. Results

4.1. Cell Viability

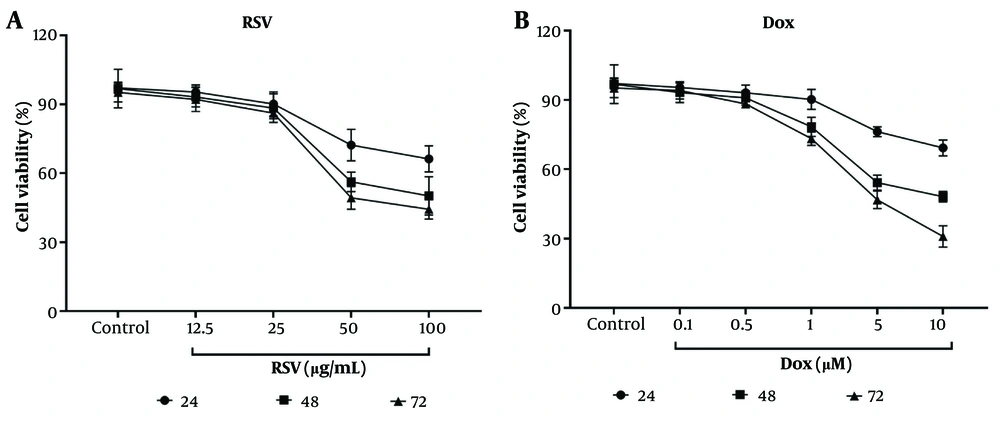

The RSV at concentrations of 50 and 100 μg/mL significantly reduced the viability of AGS cells compared to control (untreated) cells at exposure times of 24, 48, and 72 hours (Figure 1A). The IC50 of this natural compound was determined to be 50 μg/mL. In addition, both 5 and 10 μM Dox concentrations significantly reduced cell viability at exposure times of 48 and 72 hours, with the lowest cell viability observed at 10 μM Dox at an exposure time of 72 hours (Figure 1B).

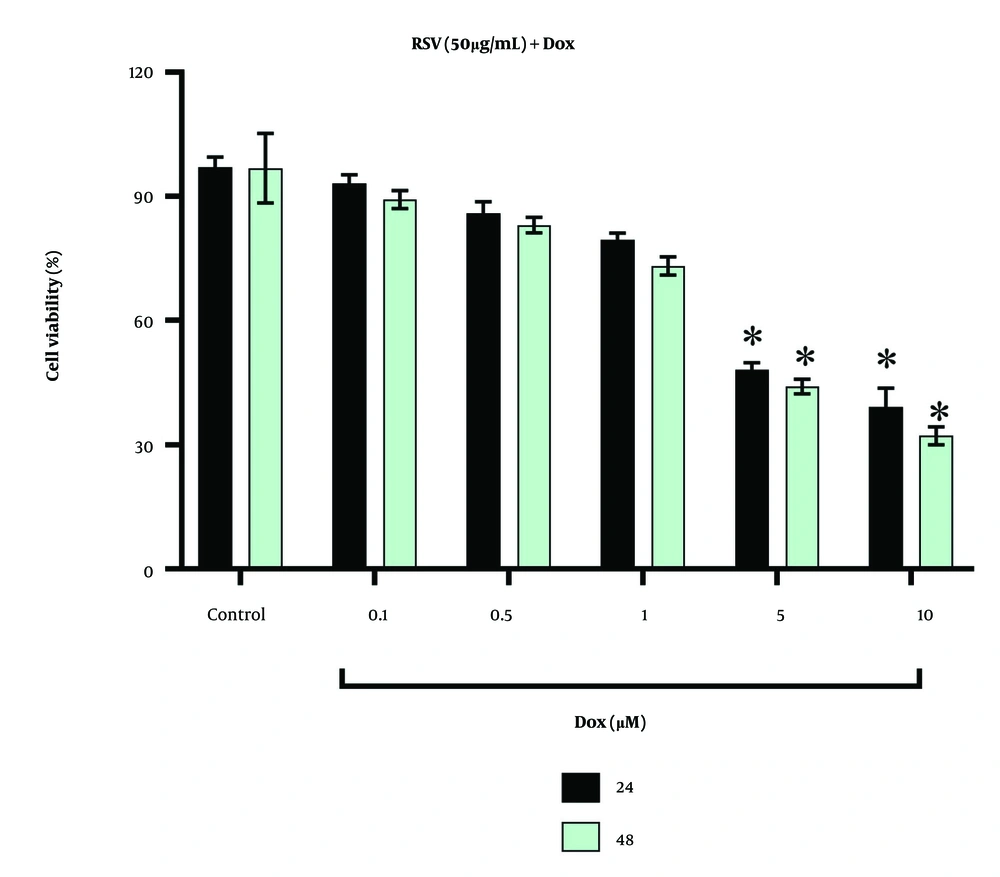

We also measured the effect of combined treatment with 50 μg/mL RSV and different concentrations of Dox on AGS cell viability at exposure times of 24 and 48 hours, and the results are shown in Figure 2. As can be seen, the combined treatment of RSV with 5 and 10 μM Dox significantly reduced AGS cell viability at both study times. The lowest cell viability was obtained at a 10 μM Dox concentration together with RSV (50 μg/mL) after 48 hours of treatment.

The impacts of co-treatments of gastric cancer cell line (AGS) with resveratrol (RSV) and different concentrations of doxorubicin (Dox) on cell viability: The viability of cells was measured by MTT assays 24 and 48 hours after treatments. * shows significant difference compared with control.

4.2. Gene Expressions

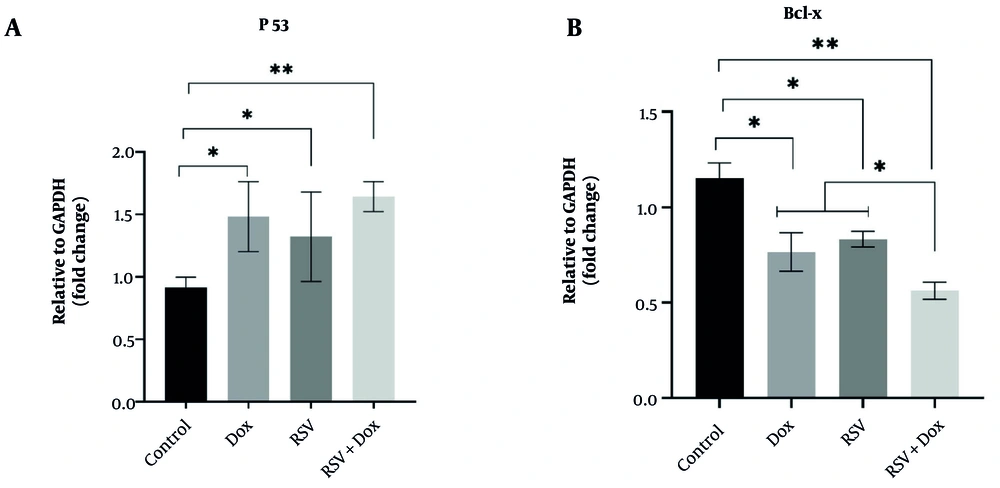

The p53 gene was overexpressed in AGS cells exposed to both Dox (1.48 ± 0.28) and RSV (1.32 ± 0.35), as well as RSV+Dox (1.64 ± 0.12; Figure 3A), while Bcl-x gene expression was significantly decreased in all three aforementioned treatments (Dox: 0.76 ± 0.10; RSV: 0.83 ± 0.04; RSV+Dox: 0.56 ± 0.04) compared to control cells (1.15 ± 0.08). However, the combined treatment of RSV+Dox resulted in the lowest level of Bcl-x gene expression in the cells, showing a significant decrease compared to AGS cells treated with RSV and Dox alone (Figure 3B).

The effects of doxorubicin (Dox), resveratrol (RSV), and RSV+Dox on p53 (A) and Bcl-x (B) gene expressions in the gastric cancer cell line (AGS, n = 3); all measurements were done after 48 hours of treatment using the RT-PCR technique. * and ** show significant differences at probability levels of P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

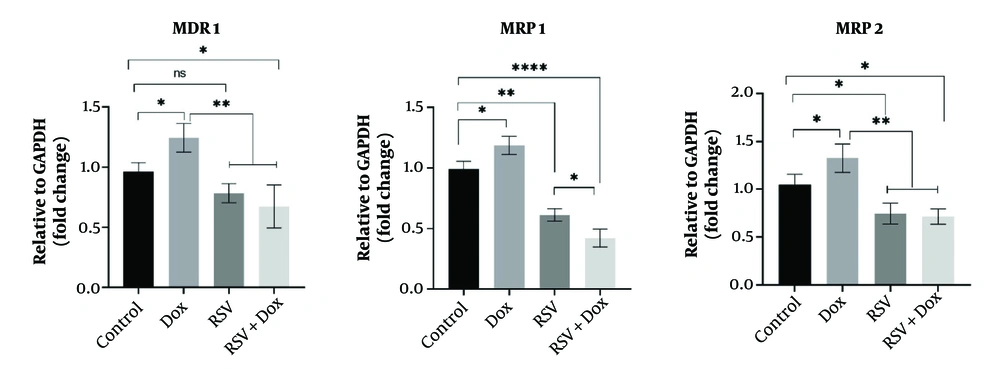

The expressions of some important genes involved in the induction of Dox resistance were studied, and the results indicated significant upregulations of MDR1 (1.24 ± 0.11), MRP1 (1.18 ± 0.07), and MRP2 (1.32 ± 0.14) genes in Dox-treated cells compared to the control (1.04 ± 0.11). However, both RSV and the combination treatment (RSV+Dox) were able to reduce the expression of MDR1 (0.67 ± 0.17), MRP1 (0.42 ± 0.07), and MRP2 (0.71 ± 0.08) genes in the cells (Figure 4). These results indicate that RSV can be considered an option to improve the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to Dox and prevent the development of drug resistance.

The effects of doxorubicin (Dox), resveratrol (RSV), and RSV+Dox on MDR1 (A), MRP1 (B), and MRP2 (C) gene expressions in the gastric cancer cell line (AGS, n = 3): all measurements were done after 48 hours of treatment using the RT-PCR technique. *, ** and **** show significant differences at probability levels of P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.0001, respectively.

5. Discussion

In the present study, it was found that RSV was able to exert cytotoxic effects on AGS cells at high concentrations (50 and 100 μg/mL). Importantly, this natural compound was able to improve the chemosensitivity of AGS cells to Dox. Decreased expressions of genes involved in inducing cancer cell resistance to Dox, such as Bcl-x, MDR1, MRP1, and MRP2, were observed in AGS cells treated with RSV and RSV+Dox, which can be considered the action mechanism of RSV in improving the chemosensitivity of cancer cells to Dox. The Dox is one of the most widely used drugs in the treatment of various types of malignancies, as it inhibits cell division, induces apoptosis, and arrests the cell division cycle in tumors (26). However, cancer cells develop resistance to Dox over time; therefore, improving the chemosensitivity of cancer cells to Dox is one of the goals of medical research (17). Recently, RSV has been shown in various studies to not only induce anticancer effects (27) but also prevent the development of drug resistance in various types of malignancies (28). In the present study, it was demonstrated that this natural compound can improve the chemosensitivity of AGS cells to Dox, indicating the prevention of Dox resistance in these cells. Therefore, in the treatment of gastric cancer, the co-administration of Dox with RSV can be considered a strategy to prevent drug resistance in gastric tumor cells.

Exposure of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents, including Dox, is associated with the upregulation of the MDR gene family, resulting in drug resistance (29). Therefore, the downregulation of this gene can prevent the development of drug resistance. One important member of this family is MDR1, whose upregulation is associated with the development of drug resistance in a wide range of malignancies, including gastric cancer (30). Therefore, we measured the expression of MDR1 after exposure of cells to Dox, RSV, and Dox+RSV. The results indicated that treatment of cells with Dox caused an overexpression of MDR1, while RSV and combined treatment with Dox+RSV prevented the upregulation of MDR1, indicating that the chemosensitivity-improving effects of RSV are mediated through the reduction of MDR1 expression.

In addition, both MRP1 and MRP2 are involved in cell resistance to Dox, and the upregulation of both genes has been reported in a wide range of cancers (31, 32). Both MRP1 and MRP2 are members of the ABC transporter superfamily, and their downregulation is a therapeutic target to counteract the development of chemotherapy resistance in cancer. Therefore, we examined the expression of MRP1 and MRP2 in AGS gastric cancer cells after exposure to RSV, Dox, and Dox+RSV. The results indicated that RSV prevented the Dox-induced upregulation of MRP1 and MRP2 in cancer cells.

It is worth noting that NF-κB is considered a hub and a key regulator in the development of drug resistance in cancer cells, and its upregulation has been reported in the development of drug resistance in a variety of malignancies (33, 34). This regulatory action of NF-κB seems to be mediated downstream of the STAT3 pathway (35). Therefore, the improvement of chemosensitivity of gastric cancer cells to Dox by RSV in this study can presumably be attributed to the effect of RSV on NF-κB expression and the reduction of STAT3 pathway activity. In fact, several studies have reported the effect of RSV on the downregulation of NF-κB (36-38). These findings suggest that RSV could potentially be considered a strategy to prevent the development of Dox resistance in gastric cancer.

However, the findings of the present study were obtained in a cellular model, and caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings to the clinical setting. Therefore, studies in animal models and clinical studies investigating the chemosensitivity-improving effects of RSV on DOX in gastric cancer are strongly recommended. After confirming its effectiveness in clinical studies, RSV can be included in gastric cancer treatment protocols.

5.1. Conclusions

Overall, it is concluded that RSV administration can be associated with improved chemosensitivity of gastric cancer cells to Dox, and these effects are mediated through the downregulation of MDR1, MRP1, and MRP2.