1. Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the death of millions worldwide (1) and has had far-reaching consequences for the physical, emotional, and economic well-being of individuals and families (2). While much research has documented the psychological toll of the pandemic — particularly the mental health consequences of losing a family member to COVID-19 (3) — the potential economic impact of bereavement remains far less studied (4). Specifically, we know little about how the death of a loved one from COVID-19 may affect individuals’ long-term sense of economic stability and certainty, especially several years after the initial loss (5).

A growing body of evidence has shown that people who lost family members to COVID-19 experienced significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress than those who did not (6). These emotional consequences are well-documented and understandable given the suddenness, scale, and trauma surrounding COVID-related deaths (7). However, while these mental health outcomes have been widely examined, much less is known about whether these losses also translate into sustained economic consequences — not in terms of income or employment status, but in how secure and stable individuals feel about their financial situation over time (8).

Perceived economic stability refers to an individual’s subjective sense of financial certainty — how confident they feel in their ability to meet financial needs, plan for the future, and withstand unexpected economic shocks (9, 10). Unlike objective measures such as household income or job status, perceived economic security captures how people experience and internalize their financial situation (11). Even in the absence of job loss, the death of a loved one can undermine this sense of stability through the loss of emotional support, financial contribution, caregiving assistance, or shared household planning (12, 13).

Despite widespread mortality from COVID-19, the longer-term economic experiences of those who lost family members have been largely overlooked (14). Most economic research related to the pandemic has focused on short-term job loss, market disruptions, or national policy responses (15, 16). Very few studies have asked whether people who lost a family member to COVID-19 continue to feel less financially stable, even several years later (13, 17).

2. Objectives

This study addresses this gap by examining whether the subjective sense of economic stability and certainty declined more sharply among individuals who lost a family member to COVID-19, compared to those who did not. We use data from the Global Flourishing Study (GFS) (18-20), a large longitudinal study conducted across multiple countries, focusing on pooled individual-level data rather than comparing countries. Our primary aim is to assess whether COVID-19 bereavement is associated with a persistent decline in perceived financial stability — an outcome that has not been directly examined in prior pandemic-related studies. We hypothesize that individuals who experienced a COVID-19-related death in the family will report greater declines in perceived financial security over time, independent of their baseline socioeconomic status.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Setting

This study is a secondary analysis of data from waves 1 and 2 of the GFS (18-20), a large-scale, longitudinal panel study designed to assess the determinants and distribution of human flourishing across diverse global contexts. Initiated in 2022, the GFS is a collaborative effort among researchers from Harvard University, Baylor University, Gallup, and the Center for Open Science. The study encompasses over 200,000 participants from 22 geographically and culturally diverse countries, including Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China (Hong Kong), Egypt, Germany, India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Tanzania, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The GFS aims to collect annual data over five years to examine various aspects of well-being, such as happiness, health, meaning and purpose, character, relationships, and financial stability (18-20).

For this analysis, we utilized data from waves 1 and 2, focusing on the association between COVID-19-related bereavement and subsequent changes in perceived economic stability. Given the study's design and the availability of relevant variables, this secondary analysis provides an opportunity to explore the long-term economic perceptions of individuals who experienced the loss of a family member due to COVID-19.

3.2. Source of Data

The GFS (18-20) is an ambitious, five-year longitudinal research initiative designed to examine the determinants and distribution of human flourishing across diverse global contexts. Launched in 2022, the study encompasses over 200,000 participants from 22 geographically and culturally diverse countries, including Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, Egypt, Germany, Hong Kong (S.A.R. of China), India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Tanzania, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These countries span all six inhabited continents, providing a comprehensive and representative sample of the global adult population (18-20).

The GFS is a collaborative effort among leading institutions, including Harvard University's Human Flourishing Program, Baylor University's Institute for Studies of Religion, Gallup, and the Center for Open Science. Its primary objective is to deepen our understanding of what it means to live well by assessing multiple dimensions of well-being, such as happiness and life satisfaction, mental and physical health, meaning and purpose, character and virtue, close social relationships, and financial and material stability. By collecting annual data over five years, the GFS aims to identify both universal and culturally specific factors that contribute to human flourishing (18-20).

What sets the GFS apart from previous studies is its unprecedented scale and depth. Unlike other cross-national surveys, the GFS provides longitudinal panel data, allowing researchers to track changes in individuals' well-being over time. This design enables a more nuanced analysis of how various factors influence flourishing across different cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Moreover, the GFS's commitment to open science principles ensures that its rich dataset is accessible to researchers worldwide, fostering a collaborative approach to understanding human well-being (18-20). Some of the advantages of the GFS include its comprehensive, longitudinal, and cross-cultural design, large and diverse sample, with robust measurements.

3.3. Analytical Sample

The analytical sample included participants who completed both wave 1 and wave 2 surveys and provided data on key variables, including age, sex, education, subjective financial stability at both time points, and responses to the question regarding the loss of a family member due to COVID-19. Participants with missing data on any of these variables were excluded to ensure the integrity of the analysis. Due to the limited number of bereavement cases in some countries, cross-country comparisons were not feasible; therefore, all analyses were conducted on the pooled global sample. A total of 128,712 participants from 23 countries were included in this analysis.

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. Perceived Economic Stability

Assessed at both wave 1 and wave 2 using a standardized self-report scale measuring individuals' confidence in their financial situation, including their ability to meet financial obligations and plan for the future.

3.4.2. COVID-19 Bereavement

Determined by participants' responses to the question: "Have you experienced the loss of a close family member due to COVID-19?" Responses were coded as 'Yes' or 'No'.

3.4.3. Covariates

We included age, sex, education level, unemployment status, baseline sense of financial security, and country of residence (the latter used only for replication analyses). Education level was categorized into three groups and modeled using two dummy variables: One for middle-level education and one for high-level education, with low-level education serving as the reference group. Unemployment was coded as a binary variable, where unemployed individuals were coded as 1, and all others — including those partially employed, not in the labor force, students, or in other categories — were coded as the reference group. Age was measured in years. Sex was coded as 1 for male and 0 for female.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

For descriptive statistics, we reported sample size (n), means, and either standard errors (SE) or standard deviations (SD), as appropriate. To examine the association between COVID-19-related bereavement and changes in perceived economic stability from wave 1 to wave 2, we conducted structural equation modeling (SEM). Given the multinational nature of the study and variation in sample sizes across countries, all primary analyses were conducted using the pooled sample. To account for potential country-level confounding, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that included dummy variables for each country (n - 1) in the model. This approach allowed us to adjust for unobserved heterogeneity across countries without engaging in direct country-level comparisons. The SEM was selected because it permits adjustment for baseline levels of perceived economic stability while modeling predictors of follow-up outcomes, allowing estimates to reflect change over time. It also enables simultaneous modeling of predictors of baseline scores. We reported only standardized beta coefficients, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), SEs, and P-values from the SEM analyses. Model fit was evaluated using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), with CFI values above 0.95 and RMSEA values below 0.05 indicating good fit. All analyses were conducted using Stata. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05, and all estimates are presented with corresponding CIs to convey the precision of results.

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

Our model also controlled for country: Argentina [reference group], Australia, Brazil, China, Egypt, Germany, Hong Kong (S.A.R. of China), India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Tanzania, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Twenty-two dummy variables were added to our sensitivity analysis. As the results did not change, we did not report the results of our sensitivity analysis.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

The study design was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Harvard University. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. No harm was anticipated, as the study did not involve any sensitive questions or procedures. All data were collected anonymously, and no personally identifiable information was included. As the data used for this secondary analysis were de-identified and publicly available, this analysis was deemed exempt from additional ethical review.

4. Results

As shown by Table 1, a total of 128,712 participants from 23 countries were included in this analysis. The sample was diverse and globally distributed, with the largest proportion of participants coming from the United States (n = 32,211; 25.03%), followed by Japan (n = 13,943; 10.83%) and Sweden (n = 11,595; 9.01%). Several other countries contributed between 4% and 6% of the sample each, including India (4.95%), Poland (5.02%), Kenya (5.98%), Germany (4.29%), and Tanzania (4.34%).

| Countries | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Argentina | 2,927 (2.27) |

| Australia | 2,580 (2) |

| Brazil | 4,271 (3.32) |

| Egypt | 3,033 (2.36) |

| Germany | 5,524 (4.29) |

| India | 6,371 (4.95) |

| Indonesia | 2,680 (2.08) |

| Israel | 2,481 (1.93) |

| Japan | 13,943 (10.83) |

| Kenya | 7,695 (5.98) |

| Mexico | 2,273 (1.77) |

| Nigeria | 3,145 (2.44) |

| Philippines | 2,681 (2.08) |

| Poland | 6,463 (5.02) |

| South Africa | 977 (0.76) |

| Spain | 2,921 (2.27) |

| Tanzania | 5,581 (4.34) |

| Türkiye | 499 (0.39) |

| United Kingdom | 3,610 (2.8) |

| United States | 32,211 (25.03) |

| Sweden | 11,595 (9.01) |

| Hong Kong | 707 (0.55) |

| China | 4,544 (3.53) |

| All | 128,712 (100) |

Countries with moderate representation (between 2% and 4%) included Brazil, China, Egypt, Nigeria, Spain, Argentina, South Africa, and Indonesia. A few countries such as Turkiye, Hong Kong, Israel, and Mexico each contributed fewer than 2.5% of the total sample. This distribution highlights the cross-national breadth of the data while also indicating that some countries, such as the United States, Japan, and Sweden, were more heavily represented in the analytic sample.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the continuous variables in the analytic sample. The mean ± SE age of participants was 49.02 ± 0.049 years, with a 95% CI ranging from 48.93 to 49.12. The average self-rated physical health (SRPH) at baseline was 7.06 on a 1 - 10 scale (SE = 0.006; 95% CI: 7.04 to 7.07), indicating generally favorable perceptions of physical health across the sample. Participants reported a mean perceived financial security score of 6.14 at wave 1 (SE = 0.009; 95% CI: 6.12 to 6.16), which remained relatively stable at wave 2, with a mean of 6.16 (SE = 0.009; 95% CI: 6.15 to 6.18).

| Variables | Mean ± SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 49.021 ± 0.049 | 48.925 - 49.118 |

| SRPH 1 | 7.055 ± 0.006 | 7.042 - 7.067 |

| Perceived financial security 1 (1 - 10) | 6.143 ± 0.009 | 6.124 - 6.161 |

| Perceived financial security 2 (1 - 10) | 6.164 ± 0.009 | 6.146 - 6.182 |

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; SRPH 1, self-rated physical health.

Table 3 presents the distribution of key categorical variables in the analytic sample. The sample was approximately balanced by sex, with 51.2% identifying as female (SE = 0.001; 95% CI: 50.9 - 51.4%) and 48.8% as male (SE = 0.001; 95% CI: 48.6 - 49.1%). In terms of marital status, 57.5% were married (SE = 0.001; 95% CI: 57.3 - 57.8%), while 42.5% were not married (SE = 0.001; 95% CI: 42.2 - 42.7%). Regarding employment status, 7.1% of participants reported being unemployed (SE = 0.001; 95% CI: 6.9 - 7.2%), and 92.9% were not unemployed, which includes those employed or otherwise not in the labor force. Educational attainment was reported in two levels. The middle education level was reported by 56.1% of the sample (SE = 0.001; 95% CI: 55.9 - 56.4%), and the high education level by 31.4% (SE = 0.001; 95% CI: 31.1 - 31.7%). Finally, 15.1% of participants reported experiencing the death of a family member due to COVID-19 (SE = 0.001; 95% CI: 14.9 - 15.3%), while the remaining 84.9% did not report such a loss (SE = 0.001; 95% CI: 84.7 - 85.1%).

| Variables | Percentage | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.512 | 0.001 | 0.509 - 0.514 |

| Male | 0.488 | 0.001 | 0.486 - 0.491 |

| Marriage | |||

| No | 0.425 | 0.001 | 0.422 - 0.427 |

| Yes | 0.575 | 0.001 | 0.573 - 0.578 |

| Unemployment | |||

| No | 0.929 | 0.001 | 0.928 - 0.931 |

| Yes | 0.071 | 0.001 | 0.069 - 0.072 |

| Education | |||

| Middle | |||

| No | 0.439 | 0.001 | 0.436 - 0.441 |

| Yes | 0.561 | 0.001 | 0.559 - 0.564 |

| High | |||

| No | 0.686 | 0.001 | 0.683 - 0.689 |

| Yes | 0.314 | 0.001 | 0.311 - 0.317 |

| COVID-19 death in the family | |||

| No | 0.849 | 0.001 | 0.847 - 0.851 |

| Yes | 0.151 | 0.001 | 0.149 - 0.153 |

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval.

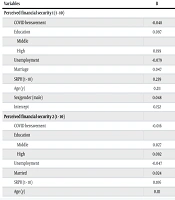

As shown in Table 4, COVID-19-related bereavement was significantly associated with a decline in financial security (B = -0.016, 95% CI: -0.020 to -0.011, P < 0.001), even after controlling for baseline financial security and other covariates. Baseline perceived financial security was the strongest predictor of wave 2 financial security (B = 0.460, 95% CI: 0.455 to 0.464, P < 0.001), indicating considerable stability over time.

| Variables | B | SE | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived financial security 1 (1 - 10) | ||||

| COVID bereavement | -0.048 | 0.002 | -0.052 to -0.044 | < 0.001 |

| Education | 0.097 | 0.003 | 0.092 to 0.103 | < 0.001 |

| Middle | ||||

| High | 0.199 | 0.003 | 0.193 to 0.204 | < 0.001 |

| Unemployment | -0.079 | 0.002 | -0.084 to -0.075 | < 0.001 |

| Marriage | 0.047 | 0.002 | 0.043 to 0.051 | < 0.001 |

| SRPH (1 - 10) | 0.239 | 0.002 | 0.235 to 0.243 | < 0.001 |

| Age (y) | 0.211 | 0.002 | 0.207 to 0.215 | < 0.001 |

| Sex/gender (male) | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.044 to 0.052 | < 0.001 |

| Intercept | 0.152 | 0.010 | 0.132 to 0.173 | < 0.001 |

| Perceived financial security 2 (1 - 10) | ||||

| COVID bereavement | -0.016 | 0.002 | -0.020 to -0.011 | < 0.001 |

| Education | ||||

| Middle | 0.027 | 0.003 | 0.020 to 0.033 | < 0.001 |

| High | 0.092 | 0.003 | 0.085 to 0.099 | < 0.001 |

| Unemployment | -0.047 | 0.003 | -0.052 to -0.042 | < 0.001 |

| Married | 0.024 | 0.002 | 0.020 to 0.029 | < 0.001 |

| SRPH (1 - 10) | 0.106 | 0.002 | 0.102 to 0.111 | < 0.001 |

| Age (y) | 0.111 | 0.003 | 0.106 to 0.116 | < 0.001 |

| Sex/gender (male) | 0.018 | 0.002 | 0.013 to 0.022 | < 0.001 |

| Perceived financial security 1 (1 - 10) | 0.460 | 0.002 | 0.455 to 0.464 | < 0.001 |

| Intercept | 0.298 | 0.012 | 0.273 to 0.322 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; SRPH 1, self-rated physical health.

Higher levels of education were positively associated with greater perceived financial security, with mid-level education (B = 0.027, 95% CI: 0.020 to 0.033, P < 0.001) and high-level education (B = 0.092, 95% CI: 0.085 to 0.099, P < 0.001) both showing protective effects. Unemployment was associated with lower perceived financial security (B = -0.047, 95% CI: -0.052 to -0.042, P < 0.001), while being married (B = 0.024, 95% CI: 0.020 to 0.029, P < 0.001), better self-rated health (SRH) (B = 0.106, 95% CI: 0.102 to 0.111, P < 0.001), older age (B = 0.111, 95% CI: 0.106 to 0.116, P < 0.001), and male gender (B = 0.018, 95% CI: 0.013 to 0.022, P < 0.001) were associated with higher financial security. All associations were statistically significant at the P < 0.001 level.

5. Discussion

This study provides new evidence that individuals who lost a family member to COVID-19 report greater declines in their perceived economic stability and certainty, even nearly four years after the loss. While previous research has demonstrated that bereavement due to COVID-19 is associated with increased psychological distress, depression, and anxiety, our findings extend this body of work by showing that such losses may also result in a prolonged erosion of people’s sense of financial security.

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed an immense burden on United States college students, who already face considerable academic and social stress. In addition to these existing challenges, many students have been directly affected by the virus — through personal illness, the death of loved ones, or pandemic-induced financial hardship. These stressors have had serious implications for mental health, yet the full extent of their impact — particularly in terms of racial disparities — remains underexplored. A study analyzing data from 65,568 undergraduate students participating in the Spring 2021 American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment (ACHA-NCHA) found that COVID-19-related stressors were not evenly experienced across racial groups. Logistic regression analyses indicated that students who experienced the death of a loved one due to COVID-19 had a 1.14 times greater likelihood of developing moderate to serious psychological distress, while those facing financial hardship had an even higher odds ratio of 1.78. Surprisingly, students who tested positive for the virus were slightly less likely to report psychological distress, with an odds ratio of 0.82. These findings suggest that indirect consequences of the pandemic, such as bereavement and financial strain, are more impactful on student mental health than the physical experience of illness itself. However, limitations such as the cross-sectional nature of the study and reliance on self-reported data mean that causal conclusions cannot be drawn. Still, the research highlights a clear need for colleges and universities to address the broader emotional and economic fallout of the pandemic by prioritizing support systems for students coping with grief and financial instability (14).

Another study explored the impact of pandemic-related family economic hardships on the mental health of adolescents in Korea during the COVID-19 crisis. Using data from 54,948 participants in the 2020 Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey, researchers conducted multiple logistic regression analyses to assess the relationship between financial strain and mental health outcomes, specifically anxiety, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation. Findings showed that 39.7% of adolescents reported slight economic hardship, 24.7% reported moderate hardship, and 5.9% experienced severe hardship. Results indicated a significant link between economic hardship and increased risk of mental health issues, with adolescents from families experiencing financial difficulties being more likely to report symptoms of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts. This association was especially pronounced among those from low to middle socioeconomic backgrounds. Overall, the study highlights the heightened vulnerability of economically disadvantaged adolescents to the long-term psychological effects of the pandemic’s financial fallout (21).

The global economic instability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has led to the loss of employment for millions of people, leaving many individuals not only to cope with the immediate emotional impact of job loss but also to face the ongoing stress and uncertainty of searching for new work. It is emphasized that psychological trauma can arise from both unemployment and the job search process, urging psychologists to pay closer attention to the effects of work–life spillover as the world continues to recover from the pandemic’s aftermath (22).

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a significant rise in mortality across the United States and globally, resulting in countless individuals mourning the sudden loss of close family members. To quantify this impact, researchers developed a measure called the COVID-19 bereavement multiplier, which estimates the average number of people who lose a close relative — defined as a grandparent, parent, sibling, spouse, or child — for each death caused by the virus. Using demographic microsimulations of United States kinship networks, along with the well-documented age-based mortality patterns of COVID-19 and various infection prevalence scenarios, a study calculated bereavement multipliers for both White and Black Americans. The findings of that study revealed that each COVID-19 death leaves about nine close relatives in mourning, meaning that if 190,000 Americans die from the virus, around 1.7 million people would grieve the loss of a close family member. These estimates remain consistent regardless of infection levels, total deaths, or their distribution, allowing researchers to track the emotional and familial burden of the pandemic alongside its mortality figures. Such studies offer detailed bereavement multipliers by age group, relationship type, and racial background, highlighting disparities in the impact of loss. Ultimately, the bereavement multiplier serves as a powerful tool to understand and monitor the broad and lasting emotional consequences of the pandemic across American families and can also be adapted to measure the impact of other causes of death (23).

Public health measures aimed at controlling the spread of COVID-19 have increasingly been recognized for their unintended consequences on socioeconomic security and health disparities, disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable populations. A longitudinal study investigated the medium- to long-term effects of the pandemic and related restrictions on financial security among families living in Bradford, a deprived and ethnically diverse city. Data were collected at four points before and during the pandemic from mothers enrolled in two prospective birth cohort studies. Results reveal a sharp increase in financial insecurity during the pandemic, which has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels. Key predictors of financial insecurity included homeowner status, eligibility for free school meals, and unemployment, while protective factors included residing in more affluent areas, higher educational attainment, and households with two or more adults. Notably, families of Pakistani heritage were at the highest risk for financial insecurity throughout the pandemic. The study found strong links between financial insecurity and maternal health outcomes, with financially insecure mothers more likely to report poor general health and significant symptoms of depression and anxiety. Such findings highlight the severe and widespread impact of financial insecurity on vulnerable families during the pandemic. In light of ongoing challenges such as the cost of living and energy crises, these studies underscore the urgent need for policymakers to implement support measures aimed at preventing further exacerbation of existing social and health inequalities (24).

A cohort study investigated the relationship between severe COVID-19 outcomes, post-COVID-19 conditions, and pandemic-related economic hardship among families in the United States, considering their socioeconomic status prior to the pandemic. Utilizing data from 6,932 families participating in the nationally representative Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) in both 2019 and 2021, the study categorized families based on whether the head of household or their partner had a positive COVID-19 diagnosis with persistent symptoms, previous severe COVID-19, or mild to moderate/asymptomatic infection, compared to families with no COVID-19 history. Key outcomes measured included layoffs or furloughs, lost earnings, and financial difficulties attributable to the pandemic. Results of the study showed that about 27% of families reported incomes below twice the poverty threshold. Adjusted regression analyses revealed that families with an adult experiencing persistent COVID-19 symptoms faced significantly higher odds — ranging from nearly two to almost four times — of economic hardship, including layoffs, earnings loss, and financial strain. Families with a history of severe COVID-19 also had increased odds, although to a lesser degree. Importantly, financial difficulties linked to persistent symptoms were elevated regardless of families’ pre-pandemic income levels, whereas severe COVID-19 was primarily associated with economic hardship among lower-income families. These findings all show that persistent COVID-19 symptoms and severe illness contribute to heightened economic vulnerability, with lower-income families disproportionately affected by employment and income disruptions following a family member’s illness (25).

Importantly, this study did not measure objective indicators such as job loss, income level, or poverty status. Rather, our focus was on how individuals feel about their financial situation — whether they perceive their financial life as stable, predictable, and sufficient to support their current and future needs. This subjective sense of economic security is known to have strong associations with well-being, stress, and long-term mental health. Our findings suggest that the emotional impact of losing a family member to COVID-19 may spill over into the economic domain, altering individuals’ confidence in their financial stability long after the acute phase of the pandemic has passed.

Several potential pathways may explain the observed association between loss of a family member and financial insecurity. The death of a close relative may result in direct financial burdens, such as funeral costs, outstanding medical bills, or the loss of shared income and caregiving responsibilities. But even beyond these tangible losses, individuals may experience disruptions in long-term financial planning, household budgeting, or the emotional resilience needed to navigate future economic uncertainty. Financial worry, when sustained over time, can further diminish confidence in one's financial outlook, creating a cycle of perceived instability that may not be fully explained by income or employment status alone.

Our findings build on, but differ from, prior research in several key ways. First, while numerous studies have documented the emotional toll of pandemic bereavement, very few have explored the long-term economic consequences as experienced by the bereaved themselves. Second, most pandemic-related economic research has focused on employment trends or national indicators rather than individual-level perceptions of financial stability. By focusing on subjective financial certainty, we identify an important and personal aspect of recovery that has likely gone unnoticed in broader economic reports. This suggests that pandemic-related losses may continue to shape lives in invisible but deeply felt ways.

From a policy perspective, these findings underscore the importance of extending the scope of COVID-19 recovery to include not just physical health and employment but also financial well-being as perceived by individuals. Support services should consider grief-related financial stress, not only in terms of income supplementation but also through counseling, financial education, and mental health services that help individuals rebuild a sense of security and future orientation.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reveals that losing a family member to COVID-19 is associated not only with emotional grief but also with a prolonged decline in perceived financial stability. As the world continues to recover from the pandemic, it is critical to recognize and address the long-lasting economic and emotional burdens carried by those who experienced personal loss. Supporting their recovery will require a broader understanding of financial well-being — one that includes not just income and employment, but also how secure people feel about their future.

5.2. Limitations

There are several limitations to consider. First, our measure of financial stability is subjective and may vary based on cultural norms, personality traits, or country context. Second, while we adjust for baseline socioeconomic factors, unmeasured confounders such as pre-pandemic financial vulnerability, household composition, or ongoing caregiving responsibilities may influence the results. Third, we lack detailed information on the role the deceased played in the household’s financial structure — such as whether they were the primary income earner or a dependent — which could moderate the observed effects.

5.3. Future Research Directions

Future research should explore whether certain subgroups — such as women, single parents, or individuals in informal labor markets — experience more pronounced financial insecurity following bereavement. Additionally, investigating the relationship between perceived economic instability and mental health over time could help identify compounding effects of grief on both economic and psychological dimensions.