1. Context

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common endocrine system disorder that primarily affects women during their reproductive years (1). This syndrome is a multifaceted psychological, metabolic, and reproductive disorder. It is defined by either elevated levels of male hormones (hyperandrogenism) or irregular secretion of specific hormones that govern the reproductive system (gonadotropins), characterized by the presence of at least one ovary over 10 mL in capacity and at least one ovary having about ten tiny cysts, measuring between 2 and 9 mm in diameter (1). Hyperandrogenic anovulation (HA) or Stein-Leventhal syndrome are alternative names for this condition (2).

Legro et al. have reported that PCOS can impact 8 - 15% of women in their reproductive years. However, the prevalence of PCOS is higher, affecting 35 - 40% of premenopausal women compared to the general population (3-5). Various clinical manifestations such as hirsutism, infertility, irregular menstruation, alopecia, and other symptoms emerge shortly after puberty and continue to grow throughout late adolescence and early adulthood. The PCOS is linked to significant metabolic consequences, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, poor glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes, and risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) (6).

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a common condition that impacts women in multiple ways. The occurrence is significantly influenced by the recommendations employed. In November 2015, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), American College of Endocrinology (ACE), and Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society (AES) released updated guidelines for the diagnosis and management of PCOS (7).

Recent advancements have deepened our understanding of the genetic, molecular, and environmental factors contributing to PCOS. Studies have identified specific genes involved in androgen synthesis, insulin resistance, and ovarian function, while the role of the gut microbiome and environmental toxins like bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates is increasingly recognized. There has also been a growing recognition of insulin resistance in non-obese women with PCOS, challenging the historical link between obesity and the condition. Emerging treatments, such as inositol isomers, show promise in improving insulin sensitivity and ovulatory function. Despite these strides, critical gaps remain, particularly in the variability of diagnostic criteria, such as the Rotterdam and National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria, which complicate diagnosis across populations. Additionally, the long-term risks of CVD and type 2 diabetes remain unclear, and the precise mechanisms linking hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and ovarian dysfunction are yet to be fully elucidated.

This narrative review aims to consolidate the current understanding of PCOS, with particular attention to evolving diagnostic dilemmas, phenotypic variability, and emerging therapies. We critically evaluate gaps in existing guidelines and propose directions for research and clinical practice.

2. Evidence Acquisition

A systematic literature search was conducted across PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases using controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms) and keywords, including "polycystic ovary syndrome", "diagnostic criteria", "insulin resistance", and "metabolic dysfunction". This review followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Data were synthesized thematically, with findings organized into mechanistic, diagnostic, and therapeutic domains. Discrepancies between studies were resolved by consensus among authors. The search encompassed publications from 2000 - 2024, prioritizing recent evidence (2015 - 2024) while retaining seminal older studies for historical context. The initial search yielded 387 records. After removing duplicates and screening titles/abstracts, 112 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Articles were excluded if they: (1) Lacked primary data or systematic methodology (n = 28), (2) focused exclusively on non-human studies (n = 11), or (3) had sample sizes < 50 participants (n = 26). Forty-seven studies met all inclusion criteria and were retained for final analysis, comprising randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, systematic reviews/meta-analyses, and clinical guidelines. Study quality was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized controlled studies (RCTs).

3. Results

3.1. Impact on Reproductive Health and Metabolic Implications

Polycystic ovary syndrome has a significant effect on women, as it causes infertility and increases the likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes and endometrial cancer. The prevalence of this condition rises in correlation with women's advancing age, as well as several lifestyle factors such as smoking, illicit drug usage, alcohol consumption, and caffeine intake. Women diagnosed with PCOS may experience fewer than six to eight menstrual cycles annually. Endometrial thickening resulting from the absence or irregularity of menstrual cycles heightens the likelihood of developing endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer (8).

Research indicates that the prevalence of obesity among women with PCOS ranges from 35% to 60%. Additional research suggests that approximately 35 - 50% of women diagnosed with PCOS have obesity (9). Obesity increases the likelihood of women with PCOS developing metabolic syndrome, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and type 2 diabetes. Polycystic ovary syndrome has a notable impact on females, stimulating a higher breakdown of cortisol. This activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, leading to heightened production of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), which subsequently results in the synthesis of androgens and estrogen (9).

3.2. Etiology

The precise cause of PCOS remains uncertain due to the intricate pathophysiological mechanisms involved. Increasing research indicates that PCOS may be associated with hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, hereditary factors, and negative emotions. Hyperandrogenemia is a crucial factor in the development of PCOS. Androgen stimulation can enhance the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), resulting in an elevation in the frequency and intensity of luteinizing hormone (LH) pulses. An overabundance of LH secretion might result in excessive synthesis of androgens. In addition, insufficient amounts of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and poor conversion of testosterone to oestradiol hinder the selection of dominant follicles, resulting in the absence of ovulation (10).

3.3. Genetic Factors and Familial Predisposition

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a multifaceted hereditary disorder involving multiple genes that increase the likelihood of developing the condition. There are numerous genes implicated in the development of PCOS (11).

3.4. Genes involved in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

DENND1A is a gene responsible for the transportation of molecules into the cell. These chemicals facilitate the retrieval of hormone receptors from the cell's surface, ultimately resulting in the development of PCOS. THADA is a gene associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and several other malignancies. It is responsible for producing hormones in the pancreas that regulate blood sugar levels in the body. The sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) gene functions as a SHBG. Low levels of SHBG serve as a biomarker for PCOS, leading to an increased amount of free hormones available in the body, which can exacerbate the symptoms of PCOS. The INSR gene is responsible for encoding the receptor that binds to the hormone insulin. These receptors are located on the outer surface of the plasma membrane and consist of three distinct regions: Extracellular, transmembrane, and intracellular (12).

3.5. Environmental and Lifestyle Factors Influencing Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Risk

Poor dietary choices, such as consuming junk food, can contribute to the development of PCOS. Junk food is high in fat, simple carbohydrates, and sugar, which increases the risk of obesity, diabetes, and CVD, all of which are associated with PCOS. This is due to the insufficient levels of progesterone in PCOS, which results in excessive activation of the immune system. Excessive consumption of junk food leads to obesity, and individuals who are obese are more susceptible to developing diabetes, which in turn increases the risk of PCOS. Insulin resistance and elevated insulin levels in the bloodstream exacerbate ovarian androgen production, which is linked to obesity (11).

3.6. Clinical Manifestations of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome is responsible for reproductive abnormalities such as menstrual irregularities, anovulation, and infertility. Menstrual irregularities occur due to anovulation, which is considered the primary factor behind infertility. Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) containing both estrogen and progestin can be utilized to decrease the activation of gonadotropins on the ovary and inhibit the generation of androgens (9). This is a significant characteristic of PCOS in adults and is frequently observed in the manifestation of PCOS in teenagers. Both chronic oligo-ovulation and anovulation are encompassed in the diagnostic criteria for PCOS in adults. Nevertheless, it is challenging to diagnose PCOS in healthy teens due to the prevalence of monthly irregularity and anovulation (13).

3.7. Hyperandrogenism

Hyperandrogenism is a defining characteristic of PCOS. Both the National Institute of Health and AES criteria require the presence of clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism to diagnose PCOS in adults. However, the Rotterdam criteria acknowledge a subtype of PCOS that does not involve excess androgens (13). Hirsutism, as assessed by the mFG score, is widely acknowledged as the most trustworthy marker of this condition (13). It refers to the abnormal and excessive development of hair on a woman's face and body (2). Acne is a persistent skin disorder characterized by the formation of blemishes and pimples. This condition occurs when the hair follicles are obstructed by a mixture of sebum and keratinocytes, resulting in the creation of whiteheads, blackheads, pimples, cysts, and other skin blemishes (2).

Alopecia is a medical disorder characterized by abrupt hair loss, resulting in baldness and hair thinning (2). Finasteride is the prescribed treatment for alopecia. This chemical functions within hair follicles to obstruct the conversion of testosterone into dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the hormone implicated in male pattern baldness. It stimulates hair growth on the scalp and inhibits further hair loss (9).

3.8. Metabolic Disturbances

Polycystic ovary syndrome is linked to metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance, obesity, T2DM, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and dyslipidemia. While metabolic characteristics are not part of the diagnostic criteria for PCOS, they should be taken into account in adolescents due to their significant impact on long-term health. Currently, the precise biochemical mechanisms underlying the connections between hyperandrogenism, obesity, and insulin resistance in PCOS remain incompletely understood (13). Both adults and adolescents with PCOS frequently experience obesity. The relationship between PCOS and obesity remains uncertain, as it is unknown if PCOS increases the likelihood of obesity or if obesity exacerbates PCOS.

3.9. Overview of Diagnostic Criteria and Challenges

3.9.1. Rotterdam Criteria

In May 2003, a symposium of experts took place in Rotterdam, primarily financed by the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. This gathering is typically designated as the Rotterdam 2003 criteria (14). The conference addressed the characteristic features of PCOS, which encompass the presence of at least two of the following criteria: Irregular or absent ovulation, elevated androgen levels, and the presence of multiple small ovarian cysts (ranging from 2 - 9 mm in diameter and/or an ovarian volume exceeding 10 mL in at least one ovary) (15). The sonographic criteria were determined according to a 2003 study conducted by Jonard et al. The study found that individuals diagnosed with PCOS had a significantly greater quantity of follicles measuring between 2 - 5 mm, in comparison to a control group composed of women experiencing infertility due to tubal or male factor issues (16). The Rotterdam 2003 criteria did not replace the NIH 1990 criteria; instead, they broadened the definition of PCOS by including two additional characteristics (14).

The generally accepted diagnosis of PCOS, which is currently prevalent, was established by a panel of specialists assembled by the NIH in April 1990. This diagnostic framework is commonly referred to as the NIH 1990 criteria. All individuals in attendance were queried regarding their perspectives on the diagnostic criteria of PCOS. The data analysis indicated that 64%, 60%, 59%, 52%, and 48% of participants identified hyperandrogenemia, exclusion of other causes, exclusion of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), menstrual dysfunction, and clinical hyperandrogenism, respectively, as criteria that were either definitive or probable for the disorder (Table 1) (14).

Abbreviation: NIH, National Institutes of Health.

a To include all of the criteria.

b To include two of the criteria, in addition to exclusion of related disorders.

3.10. Challenges in Diagnosis: Variations in Phenotypic Expression, Lack of Consensus on Diagnostic Criteria

Considering that the current criteria for PCOS have been developed through a collaborative effort between professionals and advocates in the field, it is illuminating to reflect on the statements of novelist Michael Crichton, who asserted that "the work of science is entirely independent of consensus". Politics centers on the process of achieving consensus. In contrast, science necessitates only one researcher who is correct, indicating that their findings may be confirmed by referring to the actual world. In the field of research, agreement holds no significance as the focus lies on obtaining reproducible results. The most eminent scientists in history achieved greatness precisely by diverging from the prevailing opinion. Consensus science does not exist. If a belief or conclusion is based on consensus, it cannot be seen as scientific. If a statement is scientific in nature, it cannot be seen as a consensus. Full stop. He continues his case by stating that consensus is only mentioned when the scientific evidence is not sufficiently strong (14).

3.11. Pathophysiology of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome diagnosis relies on three primary factors: Hyperandrogenism, ovarian morphology, and anovulation (1). The pathophysiology of this illness is affected by changes in steroidogenesis, ovarian folliculogenesis, neuroendocrine function, metabolism, insulin generation, insulin sensitivity, adipocyte activity, inflammatory mediators, and sympathetic nerve function. The female hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis is a precisely coordinated and rigorously controlled system vital for sustaining reproductive function and species survival. The HPO axis is activated by both internal signals, such as hormones and neurons, and external variables, such as impacts from the environment (17). According to Barrea et al. (18), the excessive intake of carbs, elevated levels of insulin, increased levels of androgens, and ongoing low-level inflammation are the four main factors that contribute to the physiological changes seen in PCOS (1).

Polycystic ovary syndrome is primarily characterized by hyperandrogenemia, which is the predominant clinical feature of the condition. Approximately 80% of women displaying indications of hyperandrogenism, such as hirsutism, acne, or alopecia, are believed to have PCOS. Androgens are synthesized in both the ovary and adrenal gland from a shared precursor molecule called cholesterol. Cholesterol is transformed into DHEA and androstenedione through a series of enzyme reactions. These reactions occur in the theca cells of the ovary and in the adrenal cortex of the adrenal gland (19).

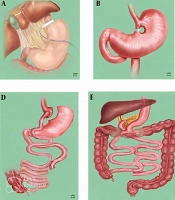

Insulin functions as a hormone that promotes cell division, in addition to affecting the breakdown and utilization of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins. The receptors for this molecule are found in several organs of the HPO axis, and it plays a role in regulating the effects of insulin (1). Hyperinsulinemia is considered the main factor responsible for excessive androgen synthesis because insulin mimics the effects of LH and indirectly increases GnRH levels. Insulin reduces the concentration of SHBG, an essential protein in the blood that controls testosterone levels (20). Figure 1 summarizes the pathophysiology of PCOS.

A schematic representation of some pathophysiological mechanisms of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (21)

3.12. Management Approaches

The primary objective of PCOS management should be to identify and address hormonal dysregulations. The fundamental approach to managing PCOS involves implementing lifestyle changes as the initial form of treatment. This includes reducing daily calorie intake, engaging in regular physical exercise, and then considering pharmacological intervention. In cases of severe obesity, weight loss surgery or bariatric surgery may be recommended (22).

3.13. Lifestyle and Weight Management

Polycystic ovary syndrome guideline recommends promoting good lifestyle choices for all women with PCOS with the aim of attaining and sustaining a healthy weight and enhancing overall well-being. For women who are overweight, it is recommended to achieve a weight loss of 5 - 10%. This can be accomplished by aiming for an energy deficit of 30% or consuming 500 - 750 kcal less per day (1200 - 1500 kcal/day) (23). The prevalence of PCOS among young women in their reproductive years is typically estimated to be between 5 and 10%. There is potential for variance within populations, where ethnic groups who are very susceptible to metabolic syndrome are also highly susceptible to PCOS (24).

3.13.1. Weight Management

Several studies conducted on individuals who are overweight or obese have demonstrated positive outcomes resulting from even a small reduction (5%) in body weight. These results encompass enhancements in general welfare, insulin responsiveness, and factors that increase the risk of CVDs. There is abundant data indicating that these benefits also extend to women diagnosed with PCOS. Research conducted on individuals with PCOS has verified that a moderate reduction in weight enhances the body's ability to process glucose, reduces the risk of cardiovascular problems, and improves reproductive function (25).

Hyperinsulinemia has a dual effect on the ovary. It stimulates the production of androgens in response to LH while also decreasing the levels of SHBG, resulting in increased amounts of free androgens. The peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogen is a contributing factor to the increased levels of estrogen, which may potentially boost the long-term risk of some malignancies (26).

Table 2 below displays the recommended daily intake for women. Women with higher body mass require more calories, and their caloric needs grow in direct proportion to their level of physical activity (27, 28).

| Variable | Activity Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary | Moderate | Active | |

| Age (y) | |||

| 19 -30 | 2,000 | 2,000 - 2,200 | 2,400 |

| 31 - 50 | 1,800 | 2,000 | 2,200 |

| > 51 | 1,600 | 1,800 | 2,000 - 2,200 |

An optimal strategy involves a synthesis of both methods. A daily caloric deficit of just 200 kcal/day will effectively prevent weight gain and facilitate weight loss over a prolonged period. An average person needs to maintain a deficit of 500 kcal/day to lose 0.5 kg/week, whereas a deficit of 1,000 kcal is required for a weight loss of 1 kg/week. These deficits are frequently challenging to attain in practical application, which elucidates why numerous individuals encounter difficulty in achieving effective weight reduction (24, 27).

3.14. Pharmacological Interventions

Pharmacological treatment for PCOS involves using clomiphene citrate, an anti-estrogen therapy (29, 30). This treatment is regarded as the conventional first-line therapy as it stimulates the release of gonadotropins and helps form ovarian follicles (31). Additionally, the insulin-sensitizing drug metformin can be utilized for the purpose of inducing ovulation. This can be done either on its own or in conjunction with letrozole or clomiphene citrate to achieve more pronounced effects (32). Letrozole has lately been proposed as the preferred initial pharmacological therapy for stimulating ovulation, potentially replacing the prior practice of using clomiphene citrate. However, combining both letrozole and clomiphene citrate may yield superior outcomes compared to using letrozole alone (30).

Oral contraceptives are the primary treatment method recommended for menstrual abnormalities and hirsutism/acne in women with PCOS, as indicated in Table 3. The OCs work by promoting the release of LH, which in turn decreases the production of androgens in the ovaries and alleviates hyperandrogenism. They elevate the synthesis of SHBG in the liver, concurrently diminishing the levels of free androgens in the bloodstream. The OCs operate by inhibiting the peripheral transformation of testosterone into DHT, binding DHT to androgen receptors, and diminishing the secretion of adrenal androgens (1).

| Treatment Options | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Clomiphene citrate | Ovulation induction |

| Gonadotropins, letrozole | Ovulation induction |

| Spironolactone | Hirsutism, acne |

| OCs | Regulation of menstrual cycles, hirsutism, prevention of endometrial cancers |

| Pioglitazone, rosiglitazone | Hyperinsulinemia, androgen excess, anovulation |

| Myo-inositol and d-chiro-inositol | Androgen excess, anovulation |

| Bromocriptine | Anovulation |

| Metformin | Hyperinsulinemia, androgen excess, anovulation |

| Sitagliptin, alogliptin, and linagliptin | Hyperinsulinemia, obesity |

| Empagliflozin | Obesity, androgen excess, hyperinsulinemia |

| Statins | Hyperandrogenism, dyslipidemia |

| Isotretinoin, spironolactone, flutamide, liraglutide, and exenatide | Weight loss, anovulation, hyperandrogenism, hyperinsulinemia |

| Eflornithine | Hirsutism |

Abbreviation: OCs, oral contraceptives.

3.15. Insulin-Sensitizing Agents

Polycystic ovary syndrome is characterized by impaired insulin secretion and dysfunction. Insulin plays a crucial role in regulating ovarian function, and elevated levels of insulin can adversely impact ovarian function. Insulin resistance is a significant contributor to the onset of PCOS and adversely impacts individuals by heightening their susceptibility to chronic health conditions, such as T2DM and CVD (33, 34). Insulin sensitizers enhance insulin sensitivity in certain tissues by decreasing insulin secretion and stabilizing glucose tolerance. Research has shown that insulin sensitizers, including metformin and thiazolidinediones (TZDs), can promote ovulation by diminishing insulin resistance (19, 21, 31).

The utilization of metformin, a type of biguanide, is associated with greater ovulation, reduced levels of circulating androgens, and improved menstrual cycles. It operates by reducing hepatic glucose synthesis, improving glucose absorption, and increasing peripheral tissue sensitivity to insulin (35, 36). A distinct RCT examined the impact of metformin on the body weight of women with PCOS who were either obese or very obese. The study revealed that the medication effectively decreased BMI without requiring any modifications to their lifestyle. Metformin has had a substantial impact on dyslipidemia in multiple trials. It either directly impacts the liver's processing of free fatty acids or indirectly operates by reducing high levels of insulin to correct abnormal lipid levels (37, 38).

In addition, TZDs (pioglitazone and rosiglitazone) decrease insulin levels by enhancing insulin sensitivity, thereby reducing the concentration of androgens in the bloodstream. Women diagnosed with PCOS have reported that the medication pioglitazone has had a positive effect in lowering insulin resistance, hyperandrogenism (excessive male hormone levels), and ovulatory failure (39, 40).

Several suggestions have been made regarding the utilization of insulin-sensitizing agents. These agents are recommended for multiple purposes, including restoring ovulation, promoting weight loss, relieving androgenic symptoms, preventing long-term complications, reducing the risk of early pregnancy loss, decreasing the likelihood of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), and potentially improving the outcome of in vitro fertilization therapy. Continuing research is being conducted to improve treatment for women with PCOS (9).

3.16. Assisted Reproductive Technology

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) is employed to address infertility. Typically, it is employed as a third-line therapy for infertility in women with PCOS. Nonetheless, it may be considered a primary option for women with clogged or compromised fallopian tubes. This treatment uses gonadotropins or clomiphene citrate to stimulate the ovaries and induce the formation of numerous follicles. To stimulate ovulation, either the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) or a GnRH antagonist is administered as the follicles attain maturity. The mature oocytes are extracted from the ovaries and combined with viable sperm for fertilization. Subsequent to successful fertilization, the embryo is placed into the endometrium. Estrogen and progesterone can be injected to prime the uterine lining. Multiple pregnancies are the most prevalent consequence of ART. This can be reduced by restricting the number of implanted embryos (9).

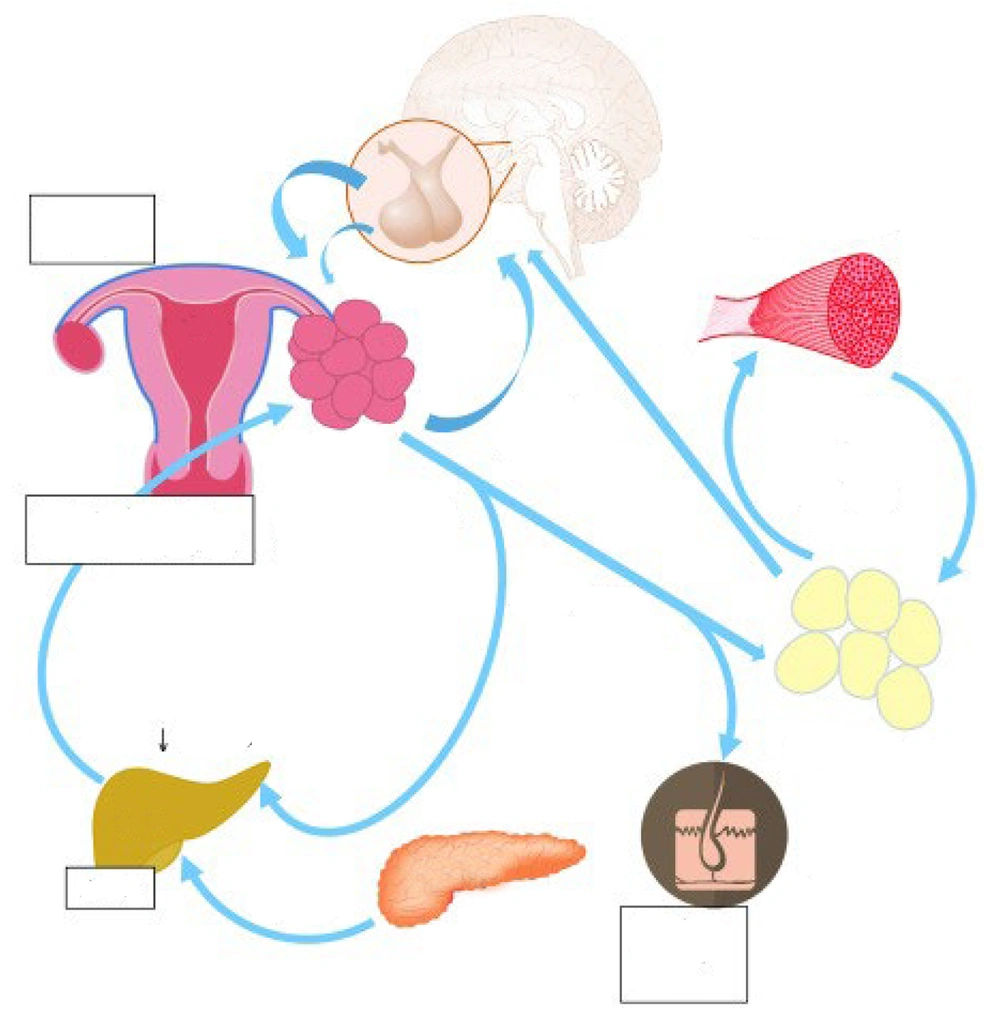

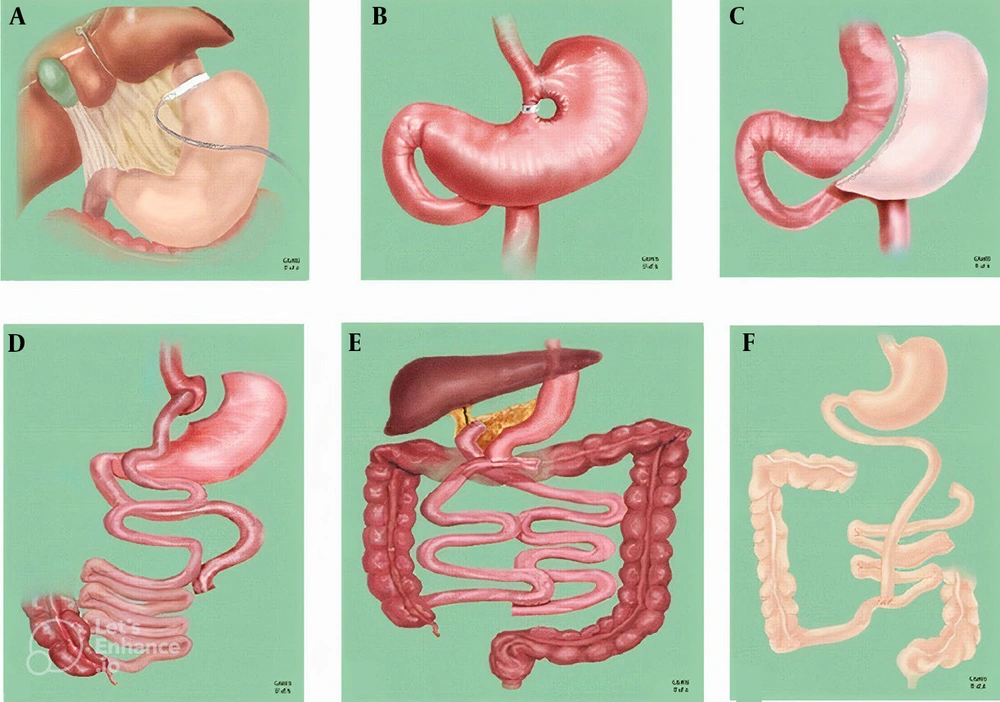

3.17. Surgical Options

Laparoscopic ovarian drilling, also referred to as ovarian drilling, is presently advised as a secure, efficient, and cost-effective substitute for gonadotropins in stimulating ovulation in infertile women with anovulatory PCOS unresponsive to clomiphene citrate. This procedure carries a lower risk of OHSS and multiple gestation. Bariatric surgery is indicated for patients who are unable to attain weight loss through dietary and physical activity interventions (Figure 2). In such instances, it provides a greater degree of long-lasting reduction in body weight. Common forms of bariatric surgery include gastric band surgery, which entails the placement of a band around the stomach; gastric bypass surgery, a procedure that connects the upper portion of the stomach to the intestines; and sleeve gastrectomy, a surgical procedure that entails the excision of a portion of the stomach, resulting in a faster sensation of fullness (9).

Bariatric surgical procedures: A; laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; B, vertical banded gastroplasty; C, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; D, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; E, biliopancreatic diversion; F, jejunoileal bypass (41).

Various studies have revealed that bariatric surgery has positive benefits on metabolic and reproductive function in individuals with PCOS. The procedure significantly enhanced hyperandrogenism and its related clinical symptoms, as well as improved menstrual periods and ovulation rates. The precise mechanisms through which bariatric surgery enhances the metabolic and reproductive profile in obese patients with PCOS are still not well understood. This increase can have positive effects on metabolism and potentially on reproduction as well. These gut peptides have the ability to decrease food intake, which is beneficial (19).

3.18. Emerging Insights

Recent advances have reshaped our understanding of PCOS, particularly regarding its heterogeneous presentations. Growing evidence highlights the significance of insulin resistance in non-obese individuals, challenging traditional obesity-centric paradigms. The role of environmental endocrine disruptors, including BPA and phthalates, has gained recognition as potential contributors to hyperandrogenism and metabolic dysfunction. Additionally, investigations into the gut microbiome have revealed distinct microbial signatures in PCOS patients, suggesting novel pathways for intervention. These insights collectively underscore the need to expand diagnostic and therapeutic frameworks beyond classical phenotypes.

3.19. Gaps and Future Directions

Despite progress, critical knowledge gaps persist. The long-term cardio-metabolic consequences across PCOS phenotypes, especially in lean women, remain inadequately characterized. Ethnic variations in diagnostic markers and treatment responses require further validation through large-scale, longitudinal studies. Furthermore, the development of targeted therapies tailored to specific pathophysiological subtypes — such as those driven primarily by insulin resistance versus hyperandrogenism — demands urgent attention. Addressing these gaps will be essential for advancing personalized management strategies and improving outcomes in this complex syndrome.

4. Conclusions

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a prevalent endocrine disorder affecting approximately 1 in 15 women globally, with heterogeneous presentations spanning reproductive, metabolic, and psychological domains. While diagnosis remains clinical, significant challenges persist — particularly in adolescents, where Rotterdam and NIH criteria exhibit limitations due to overlapping pubertal changes. Current management often prioritizes short-term reproductive outcomes over long-term metabolic risks, underscoring the need for phenotype-specific strategies. Our proposed algorithm in management approaches tailors interventions to dominant features (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, or anovulation), addressing this gap.

Emerging evidence highlights subtype-specific pathophysiological mechanisms, yet critical questions remain unresolved: Ethnic variations in phenotypic expression, biomarker validation, and cardiovascular risks in lean PCOS. Future research must prioritize these areas to enable precision screening and therapies. By advancing a unified framework for diagnosis and personalized care, we can mitigate both immediate symptoms and lifelong health burdens in this diverse population.