1. Background

Prenatal screening tests are essential parts of modern obstetric care, providing critical data regarding fetal health and growth during pregnancy (1, 2). These tests aim to evaluate the likelihood of specific genetic and congenital disorders, enabling both expecting parents and healthcare professionals to make informed decisions (3, 4). The advancement of prenatal screening began in the 1970s with the maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) test used to detect neural tube abnormalities. Since then, the field has considerably widened with various options such as ultrasonography, blood tests, and more recently, non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) that examines cell-free fetal DNA in maternal blood for detecting genetic mutations and disorders (5, 6). Despite the benefits, prenatal screening tests also raise important medical, ethical, and legal considerations (7, 8). The implications of test results can profoundly affect parental decision-making, including the choice to pursue further diagnostic testing or consider termination of pregnancy based on perceived risks. Consequently, debates on informed consent, the possible anxiety arising from unclear results, and the social effects of selective screening procedures are becoming increasingly important in the field of prenatal care (7, 9, 10).

2. Objectives

Given the aforementioned, the concept of prenatal screening tests is more complicated in Islamic nations like Iran, due to political, legal, cultural, and religious restrictions (11, 12). As these are not profoundly studied, in the present study, we aimed to examine prenatal screening tests from the perspective of medical ethics and law in a qualitative research study in Iran.

3. Methods

In this qualitative study, we carried out semi-structured interviews with gynecologists and professors of genetics and medical ethics, as well as a neonatal specialist in Rasht, Iran. For this study, we employed a qualitative research approach using explorative narrative interviews. The goal of this interview method was to gain a deep understanding of the interviewees' personal perspectives, experiences, and interpretations related to the research topic. The design of the interview questions and the identification of key themes were intended to elicit responses that are relevant to both the interview topic and the backgrounds of the interviewees. As a survey method, exploratory interviews offer a certain flexibility by allowing us to ask ad-hoc questions in order to clarify statements or to focus on particularly important issues. The criteria for inclusion in the study required participants to be willing to take part and provide informed consent, to have the ability to comprehend the questions, to be able to read and write, and to not have any diagnosed psychological disorders.

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted in Guilan province during March and April 2023. Sampling and interviews continued until data saturation was achieved, resulting in a total of seven participants (n = 7), including four gynecologists, one neonatologist, one PhD in genetics, and one PhD in medical ethics. All interviews were conducted face-to-face. The sessions were led by two researchers who hold PhD degrees and possess expertise in the research topic and qualitative research methodologies. Interviews focused on four questions: (1) What are the challenges of screening? (2) What are the challenges of not doing screening? (3) Can the risks of screening be a reason not to do it? (4) Why are safe methods not used? To ensure validity, the study employed the Content Validity Index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) for assessing content validity. Regarding the CVI, all questions across three sections demonstrated simplicity, clarity, and relevance scores exceeding 0.7, while the CVR for all questions was also above 0.7.

Data collection involved obtaining informed consent from participants and conducting interviews either in person or by telephone. The interviews, lasting an average of 30 minutes, focused on four central questions. Probing questions were used to further explore participants' insights. The interviews revealed new dimensions of the topic as the study progressed, allowing the interviewer to refine subsequent discussions. Qualitative data were analyzed using Granheim and Landman’s method (13) for conventional content analysis. Most interviews were recorded. The coding process in this qualitative study was carried out as follows: All interviews were carefully read multiple times to allow the researchers to become thoroughly familiar with the data. Meaning units relevant to the research objectives were extracted and identified. These meaning units were manually coded into initial codes and recorded in a coding table. Similar codes were grouped into conceptual clusters, and through a gradual categorization process, subcategories and eventually main categories were extracted. The coding and categorization process was conducted inductively and continued based on the repetition of concepts and data within the interviews until data saturation was reached. Finally, data analysis was performed independently by two researchers, and the results were compared and reviewed to increase the reliability of the findings.

Prior to the commencement of the study, no prior relationship had been established with the interviewees. At the start of each interview, the participants were provided with information about the research objectives and procedures, assured that their participation was voluntary, and informed about the measures taken to protect and archive the data collected during the interviews. Consent was also obtained regarding the publication of results in an anonymized format. Since the research questions did not specifically investigate the influence of individual characteristics of the interviewees, such as age, gender, career path, or professional background, on the research topic, no demographic data were gathered during the interviews. Data analysis was performed utilizing content analysis and thematic analysis techniques (14). Initially, the interviewees' responses were distilled into essential elements and statements. These elements were then manually coded, extracted, and organized into main topics and subtopics through clustering. The topics were developed inductively based on the interview content to identify significant and recurring themes, as well as variations in the responses.

4. Results

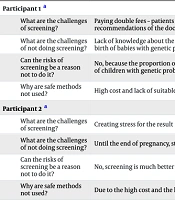

In this study, 10 people were arranged to conduct interviews, and three of them did not want to cooperate. Out of the 7 interviewees, 4 women were gynecologists, one man had a degree in neonatology, one woman had a doctorate in genetics, and one man had a doctorate in ethics. Table 1 shows an overview of the thematic focus of each individual's responses. These thematic focus points determine the structure of this section.

| Participants | Thematic Focus of the Responses |

|---|---|

| Participant 1 a | |

| What are the challenges of screening? | Paying double fees – patients neglecting screening due to lack of awareness of the importance of doing it, despite the repeated recommendations of the doctor. |

| What are the challenges of not doing screening? | Lack of knowledge about the genetic structure of the fetus, which can cause the failure to perform the required medical treatments – the birth of babies with genetic problems |

| Can the risks of screening be a reason not to do it? | No, because the proportion of negative consequences of the screening procedure is much, much smaller than the injuries caused by the birth of children with genetic problems. |

| Why are safe methods not used? | High cost and lack of suitable kits in the country |

| Participant 2 a | |

| What are the challenges of screening? | Creating stress for the result |

| What are the challenges of not doing screening? | Until the end of pregnancy, stress is remained for the mother and the doctor – maintenance costs in case of birth defects. |

| Can the risks of screening be a reason not to do it? | No, screening is much better than not screening. |

| Why are safe methods not used? | Due to the high cost and the lack of insurance coverage, the cell free fetal DNA method is not used. |

| Participant 3 a | |

| What are the challenges of screening? | Since screening methods are not definitive, they must be confirmed with amniocentesis, and this procedure can cause pregnancy loss, bleeding, infection, and premature birth. |

| What are the challenges of not doing screening? | It takes away the chance of early diagnosis of the anomaly and imposes a double cost for the treatment. |

| Can the risks of screening be a reason not to do it? | No, screening is much better than not screening. |

| Why are safe methods not used? | High cost and the need for confirmation with amniocentesis |

| Participant 4 a | |

| What are the challenges of screening? | Imposing a high cost on the society that needs government support – false positive answers, more stress and more expensive examinations are required. |

| What are the challenges of not doing screening? | Failure to perform screening also results in the chance of birth of chromosomal abnormalities that impose a lot of financial and psychological costs on the family and society, which cannot be compared to the costs of screening, and prophylaxis and prevention of damage have been proven. It will have less cost and burden for the family, health system and society. |

| Can the risks of screening be a reason not to do it? | No, abortion caused by amniocentesis is not significant in addition to the low probability compared to the benefits of this method. |

| Why are safe methods not used? | It is used, today, in many cases, the cell free fetal DNA method has routinely replaced invasive methods such as amniocentesis. |

| Participant 5 b | |

| What are the challenges of screening? | High cost, mothers' lack of knowledge about gender issues, lack of full insurance coverage, limitation of screening centers |

| What are the challenges of not doing screening? | In case of birth of a defective baby, heavy costs are incurred by the family and the government, and it has various economic, social and psychological consequences for the child's parents. |

| Can the risks of screening be a reason not to do it? | In my opinion, its benefits are more than its disadvantages. |

| Why are safe methods not used? | The necessary equipment is either not available in Iran, or has very high costs, or has more of a study role and has not yet been included in the country's guidelines and instructions. |

| Participant 6 c | |

| What are the challenges of screening? | Tests performed can give false positive results that indicate the presence of a problem in the fetus, when in fact it is not. This can lead to the anxiety of a false positive result and lead to more tests that are themselves dangerous, such as amniocentesis or ultrasound with curettage. Likewise, the accuracy of these tests can be limited. |

| What are the challenges of not doing screening? | Missing early detection opportunities is a problem that happened recently and stuck in my mind. Pregnancy tests are important because of the diagnosis of most health problems of the pregnancy process. Without these tests, serious health events may not be detected until after the baby is born, causing delays in treatment and more serious consequences for the baby's health. |

| Can the risks of screening be a reason not to do it? | In my opinion, it comes back to the parents. Humans have many differences, especially in psychological issues, one should not use the same prescription for everyone. |

| Why are safe methods not used? | I don't know anything about the method. |

| Participant 7 d | |

| What are the challenges of screening? | High cost, non-acceptance of the truth by parents, non-acceptance of risk, difficulty of access |

| What are the challenges of not doing screening? | Practically, not performing screening tests means accepting the possibility of any congenital defect for the fetus. |

| Can the risks of screening be a reason not to do it? | Yes, the risks associated with fetal screening can be a reason not to perform it. But it should be noted that fetal examinations can provide important information about the health of the fetus to the doctor and the family, and it is up to them to decide whether they want to do these examinations or not. |

| Why are safe methods not used? | The mentioned methods are not available everywhere and are very expensive. |

a Gynecologists.

b Professors of genetics.

c Medical ethics.

d Neonatal specialist.

5. Discussion

The overlap of medical ethics and law regarding prenatal screening and pregnancy termination serves as a complex landscape, particularly in Iran, where cultural, religious, and legal frameworks profoundly impact decision-making processes (15, 16). This qualitative study aimed to explore the perspectives of healthcare professionals in Iran on the ethical and legal challenges associated with fetal testing. The findings demonstrate a conflict between the concept of patient autonomy and the healthcare provider's responsibility to prioritize the health of both the mother and the fetus. Although prenatal screening provides significant medical advantages, such as early detection of genetic abnormalities, participants in this study expressed concerns regarding the practical, financial, psychological, and ethical difficulties in performing these tests successfully and efficiently. As mentioned, it can be complex to balance patient autonomy and medical benefit in prenatal care decision-making. The concept of autonomy emphasizes the necessity of enabling patients to make informed decisions about their treatment; nevertheless, this is sometimes confounded by the complicated nature of fetal screening (11, 17).

One of the primary challenges discussed by participants was the financial burden of prenatal tests. High costs and limited insurance coverage were repeatedly cited as barriers to using advanced screening methods such as NIPT (18-20). These financial barriers can lead to disparities in access to essential prenatal care, with lower-income families potentially forgoing screening altogether due to its expense. This inequality in access raises ethical concerns about the fairness and justice of healthcare provision, especially in a system where screening could prevent long-term financial and emotional costs associated with caring for a child with a congenital disability. Addressing these financial obstacles requires comprehensive policy changes focused on improving insurance coverage and reducing personal costs for vital prenatal tests (21-23).

The psychological impacts of prenatal screening on expectant parents are a notable concern, particularly in relation to false-positive outcomes (24-26). Research demonstrates that women undergoing prenatal diagnostic procedures commonly experience higher levels of anxiety and psychological distress, which may be underestimated in clinical settings. Studies indicate that women who undergo invasive tests report significantly greater anxiety levels compared to those who have not yet been screened or who have received reassuring results from anomaly scans, influenced by factors such as uncertainty from healthcare providers, financial concerns, and prior adverse experiences (24-28).

This study has some limitations. The qualitative method used for the research, while beneficial for in-depth exploration of the views of professionals, unavoidably restricts the generalizability of the findings. The limited sample size may not comprehensively represent the general population of healthcare professionals. The involvement of specialists from particular domains offers a concentrated yet restricted perspective on the issue. Further studies with larger sample sizes, involving a wide variety of healthcare providers and also parents, are needed.

5.1. Conclusions

This research highlights the complex interaction among ethical, psychological, and practical issues in prenatal screening in Iran. Medical professionals emphasize the necessity for a broader strategy that includes not just the medical and technological aspects of prenatal testing but also wider ethical, legal, and social considerations.