1. Context

Today, burn wounds are common and cause major health problems in different parts of the world. In addition, burns are known as one of the major types of injury, and statistics indicate that 1% of people around the world are affected by actual burns, with 70% of deaths in burn patients occurring due to wound infections (1). The latest reports from the World Health Organization also state that 180,000 deaths occur due to burns, leading to a global health challenge that imposes significant costs on healthcare systems (2). Burns are mainly caused by exposing the body to heat, which results from the transfer of energy from a heat source to the body. The severity of the burn depends on the intensity of the heat, the length of time the body is exposed to the heat, and the ability of the involved tissues to withstand it. Burns cause necrosis of subcutaneous tissues and result in cell damage to varying degrees (3,4).

Researchers believe that the type of burn and the cause of death are related to the age, social status, and occupation of individuals. Additionally, it has been stated that about 75% of burn cases are due to accidents. In home settings, burns occur due to problems escaping from fire and its dangers, which in most cases lead to hospitalization. About 30% of people get burned due to contact with hot liquids (5, 6). Also, bacterial infections of burn wounds are common, with gram-negative organisms such as Klebsiella, Serratia, Pseudomonas, and Enterobacteriaceae being isolated from these wounds. Furthermore, endotoxin secretion by some gram-negative bacteria causes toxic effects on cell division, inhibiting the immune system along with systemic symptoms and shock (5, 7-9).

In an Iranian study on burn patients in the southeast of Iran, 33 cases (25.41%) had bacterial infections (10). In the study by Mamani et al. in Hamadan, bacterial infection was most common among burn patients, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa reported in 27.7% of cases (10). Furthermore, fungal burn wound infections are among the most severe problems in patients who are seriously burned (11). Burn wound infections remain the most important factor limiting survival in burn patients. Damaged immune systems and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy facilitate the growth of opportunistic fungal species (spp.). Other predisposing factors include increased age, long hospital stays, steroid treatment, long-term mechanical ventilation, uncontrolled diabetes, and the presence of central venous catheters (12, 13). More severely injured patients with greater total body surface area (TBSA) burn injury and full-thickness burns require a longer recovery period, resulting in a longer hospital stay. The tendency for fungal infection increases the longer the wound is present (14). Fusarium spp. are pervasive fungi recognized as opportunistic agents of human infections and can produce acute infections in burn patients (15). Infection starts with the inhalation of Fusarium conidia or direct contact with substances contaminated with Fusarium conidia. Subsequently, conidia germinate and form filaments that attack the surrounding tissue when an appropriate environment is provided (16). Burned skin acts as a gateway for the entry of fungi, and the compromised immune status facilitates deep invasion (17). To the best of our knowledge, no study has comprehensively analyzed the different dimensions of fungal infections and strategies for prevention in burn patients.

2. Objectives

This systematic review responds to the following research questions:

- RQ 1: What is the mortality rate of burn patients with Fusarium fungus?

- RQ 2: Which spp. of Fusarium fungus most affect burn patients?

- RQ 3: What types of media have been used to identify Fusarium fungus?

- RQ 4: What treatment methods have been used for burn patients with Fusarium fungus?

- RQ 5: What is the percentage of burn (total body surface) in patients?

- RQ 6: What are the age and sex of people with Fusarium burns?

- RQ 7: What are the best strategies to prevent fungal infections in burn patients?

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

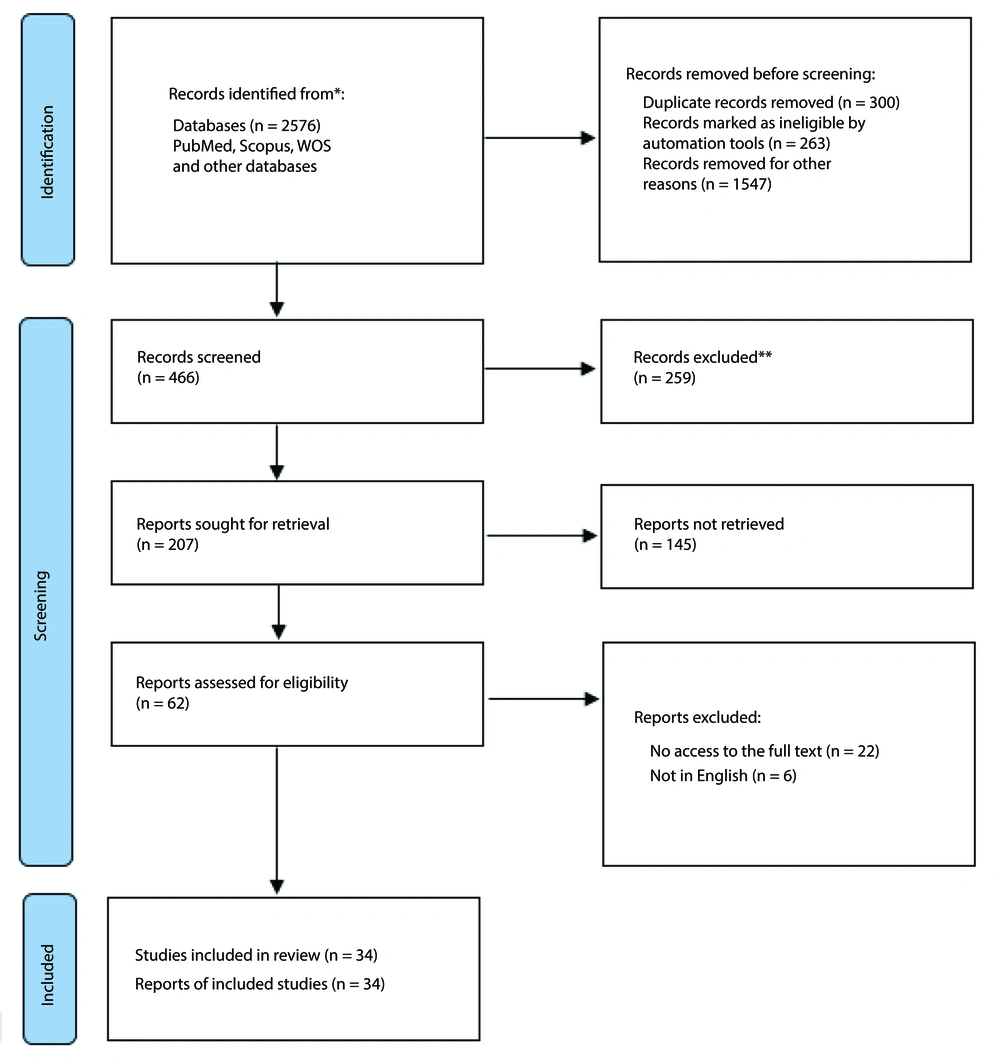

This systematic review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) proposed by Moher et al. (18). Figure 1 displays the PRISMA process for data collection and analysis.

3.2. Search Strategy

The papers from PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science databases, and Google Scholar search engine were searched with a time limitation (2000-August 2025). The PICO criteria were used to define the search string: Population (P), intervention (I), comparison (C), and outcome (O) (19). The population was burn patients, interventions included Fusarium fungus, comparison was excluded, and the outcomes were the results of treatment of patients and mortality rate.

The search string in PubMed was: [Fusarium (MeSH) OR “Fusarium*” (tiab) OR “Gibberella” (tiab) OR Fusariosis (MeSH) OR “Fusariosis” (tiab) OR “Fusarium infection” (tiab)] AND [burns (MeSH) OR “burn*” (tiab)].

In Scopus, the search string was: TITLE-ABS-KEY: (“Fusarium*” OR “Gibberella” OR “fusariosis” OR “Fusarium infection”) AND (“burns” OR “burn*”).

In Web of Science, the search string was: [TS=(“Fusarium*” OR “Gibberella” OR “fusariosis” OR “Fusarium infection”)] AND TS=("burns" OR "burn*").

3.3. Study Selection

The criteria for including the retrieved articles in the study were that the articles addressed at least one of the objectives of the current research within the period from 2000 to August 2025. Articles published outside this period, in languages other than English, or without available full-text formats were excluded from the study. It is important to note that gray literature was not included in this study. Articles or case series primarily focusing on fungal infections resulting from burns were analyzed. Using different search strategies in the first stage, 2,576 documents were retrieved from the selected databases. The bibliographic information of the retrieved primary documents was transferred to the 7th edition of EndNote resource management software. After removing duplicates based on inclusion criteria, the titles and abstracts of articles were reviewed by two independent reviewers, and if any disagreement was observed, the explanations of a third reviewer were applied. After identifying and removing duplicate and unrelated documents, 34 related studies were selected for final review (Figure 1).

3.4. Quality Appraisal of Studies

After the initial review of the studies, three authors convened a meeting and reached a consensus on the quality assessment of each study. Due to the diversity of available articles and methods, the Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT) 2018 version was employed to evaluate each study (20). To minimize bias, three independent evaluators assessed the studies, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion or with the involvement of a fourth evaluator.

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection

The systematic review of the databases included 2,576 articles, of which 300 were duplicates and excluded. Of the remaining articles, 1,547 were excluded based on their titles, and 263 were excluded based on their abstracts. After full-text screening of the remaining 62 articles, 28 were excluded according to the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, 34 articles were identified as eligible for review (Figure 1).

4.2. Quality Appraisal

Findings from the quality assessment of the articles showed that all articles were eligible based on MMAT scores ranging from 80 (moderate, n = 3, 17.22%) to 100 (high, n = 29, 82.2%). Given the different study designs in the reviewed studies, we used the MMAT tool to assess their quality. The research questions in all studies were clearly stated, and the data collected provided an opportunity to answer these questions.

4.3. Study Characteristics

The results of the study show that, from a methodological point of view, the 34 retrieved articles were mostly case reports. Analysis of the demographic information of burn patients in the studies indicated that they are in the age groups between 3 to 82 years. Fungal spp. Fusarium, Aspergillus, and Mucor were observed in different histopathological cultures and biopsies. Other findings related to the aims are presented in Table 1.

| Writers and References | Type of Study | Demographic/Mortality Rate/Burning Percent | Types of Fungi | Specimens | Important Results/Signs and Symptoms; Prevention or Treatment Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheeler et al. (11) | Case reports | NA | Fusarium spp., Fusarium oxysporum | Burn wounds | The incidence of fungal infections in burn patients has been growing because of the enhancement in antibacterial chemotherapy. Best strategy prevention: (1) Careful wound care: Usage of clean and sterile techniques in burn wound care and prevent fungal infections; (2) microbial surveillance: Perform regular microbiological tests, including colonic biopsies and histological and mycological examinations, for rapid and accurate identification of fungal infections. |

| Latenser (12) | Case report | A 40-year-old white male; 73% grease scald injury/patient died 55 days after injury | Fusarium spp., Candida spp. | Debridement, excision, and skin grafting | Deep-tissue involvement happens in immunocompromised patients with hematologic malignancies, aplastic anemia, and chemotherapy treatment. Monitoring high-risk patients: Cancer patients, those undergoing chemotherapy, and those with extensive burns should receive special care and close monitoring. |

| Hai et al. (13) | Case report | 53-year-old patient/the patient not recovered | F. equiseti | Histological examination (periodic acid-Schiff) and biopsy sampling | Antifungal susceptibility test is essential because multidrug resistance is usual among Fusarium strains/aggressive treatment/IV voriconazole. Management of the use of unconventional herbal medicines in burns, standard care and infection control measures, active surveillance, and increased attention to traditional medicines should be considered. |

| Tu et al. (14) | Case report | 44 burn patients/overall mortality rate 27.27% | Candidaalbicans, Fusarium spp., Zygomycetes | Surgical excision, debridement, skin graft, vitrectomy, teeth extraction, valve replacement, or amputation | The general mortality of fungal wound infection is high in burn patients around the world, markedly those infected with non-Candida spp. The three key factors or appropriate strategies are early diagnosis of fungal infection, early initiation of appropriate antifungal therapy, and effective surgical intervention to follow up on infection in burn patients. |

| Tram et al. (15) | Case report | 24-year-old male; extensive injuries 75% of body/the patient did not recover | F. solani;C.tropicalis | Histological examination of skin biopsy speimens; blood culture | F. solani was identified the most frequent pathogenic agent among Fusarium spp. 3 antifungal drugs caspofungin, fluconazole (for C. tropicalis), and voriconazole have been used for treatment, but were not effective against Fusarium. |

| Spesso et al. (16) | Retrospective study | 168 patients admitted to ICU, 29 burn patients; 13 male and 16 female; mortality rate of patients (24%) | Aspergillus spp.; Fusarium spp.; Mucor spp.; dematiaceous fungi | Skin biopsies and bedsores | Mortality among patients was 24% and Fusarium was involved in the highest number of deaths (50%). |

| Schaal et al. (17) | Retrospective study | 1849 patient/31 case have fungal infection/24 male and 7 female/6 cases of 22 people died | Aspergillus spp. (24 case); Fusarium spp. (3 case); Mucor spp. (9 case) | Biopsies or superficial swabs; wound biopsy; Sabouraud’s dextrose agar with and without chloramphenicol and blood agar | Filamentous fungal infections are basically cutaneous and rare and occur in the most severe burns. Voriconazole; amphotericin B; itraconazole; posaconazole; flucytosine; lipid formulations of amphotericin B three key prevention strategies include environmental controls (high air exchange rates, overpressurized operating rooms and operating theatres, etc.), use of infection control practices (strict aseptic techniques during dressings), and other additional measures such as proper maintenance and operation of preventive devices. |

| Rosanova et al. (21) | Retrospective, descriptive study | 15 patients/burn surface area (45%)/1 patient died | Fusarium spp. | Burn wound | Fusarium spp. was an unusual pathogen in severely pediatric burnt patients (amphotericin B, voriconazole). |

| Park et al. (22) | Case report | 82-year-old man with diabetes | Bisifusarium delphinoides, F.dimerum spp. complex | Deep swab specimen | Both diabetes mellitus and burns can be risk factors for Fusarium infection. |

| Palackic et al. (23) | Review | NA | C.albicans, Aspergillus and Zygomycetes, non- albicans Candida spp. | Debridement | The development of antifungal drugs is necessary due to the presence of drug-resistant fungi. Amphotericin B and voriconazole; Early radical debridement and wound closure are essential to prevent infection. Empirical prophylactic drug therapy should be considered for individuals at high risk of invasive burn wound infection. |

| Khalid et al. (24) | Case report | 8 patients from 3 - 57 y | F.dimerum | Debridement | Fusarium was responsible for 50% of deaths in burn patients (amphotericin B or voriconazoles). |

| Katz et al. (25) | Retrospective Study | Adult burns patients/two case died | Aspergillus fumigatus, Scedosporium prolificans, F. solani, Mucor spp., Absidia corymbifera, Penicillium spp., Alternaria spp. | Biopsy | Fungal or Candida infections have low mortality in the context of primary antifungal treatment; Important strategy early antifungal therapy extensive surgical debridement. Early closure of burn wounds, frequent microbiological evaluation of burn wounds, and aggressive surgical debridement of burn wounds are emphasized to prevent infection. |

| Goussous et al. (26) | Case report | 55-year-old male/35% TBSA | F. solani | Debridement tissue/elbow amputation | The risk factors of Fusarium are increased burns on total body surface, length of hospitalization, polymicrobial infections and the presence of inhalation injury; aggressive approach |

| Carrillo-Esper et al. (27) | Review | 26 cases | F. solani | NA | Immunosuppression and skin loss increase the frequency of fungal infections; voriconazole, posaconazole, and the lipid formulations of amphotericine B |

| Barrios et al. (28) | Case report | An adult burn patient/35% total body surface/improved | F. solani | NA | Focal neurologic deficits; Prolonged course of IV triple antifungal therapy |

| Piccoli et al. (29) | Review/24 case reports | 87 burn patients/1 to 85 y/male (53%) and female (47%)/78% burn surface/23 patients (37%) died | F.dimerum spp. complex | Histopathology | Amphotericin B voriconazole given the relatively high reported mortality rate of 37% of case reports, increasing understanding of the epidemiology of Fusarium and emphasizing clinical care among burn patients is critical for prevention. |

| Yen et al. (30) | Review | 81-year-old male/45 % of body surface | Fusarium spp. | Biopsy | Staphylococcus and Bacillus burn wound infections; Acinetobacterpneumonia; Cefazolin, ceftazidime, gentamycin |

| Barragan-Reyes et al. (31) | Retrospective series | 49 cases/22% of patients not recover. | Fusarium spp. | Biopsy/histopathology | Burn injuries (49%)/37% had hematological malignancies/monotherapy voriconazoleamphotericin B. |

| Jin et al. (32) | Case report | Average burnt 83.03% TBSA/13 male and 3 female/mortality rate (43.75%) | Candida spp., Fusarium spp., Aspergillus spp. | Bacteriological/organism | The most common fungi were Candida, Fusarium, Aspergillus, and fumigatus; In patients with burns caused by mass burn accidents, contact with water or soil should be considered as pathogenic and accelerating factors for infection for better prevention. |

| Akhavan et al. (33) | Retrospective review | 37 patients with atypical invasive fungal infections/five patient deaths (13.8%) | Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp., Mucor spp. | NA | Aggressive treatment, first infectious disease consultation |

| Stevens et al. (34) | Case report | 40-year-old/died on hospital day 167 | Fusarium spp. | NA | Fungal brain abscess aspiration antifungal therapies |

| Delliere et al. (35) | Retrospective analysis | 15 patients | F. solani | Biopsy/histopathology | Pan-Fusarium qPCR assay in serum/plasma with high sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility/circulating DNA for the diagnosis |

| Farooqi et al. (36) | Case report | 140 cases | Candida spp. Fusarium spp. | Bacterial cultures | Control and assess the frequency of fungal isolation in wound specimens |

| Louie et al. (37) | Case report | 1 case ill burn-injured patient | Fusarium spp. | Biopsy/scrapping | Topical liposomal amphotericin |

| Smolle et al. (38) | Case report | 17-year-old woman; 17% total body surface | Fusarium spp. | Wound swabs | Omega 3; Appropriate infection control and prevention strategies, in case of additional trauma complications, wound infection with resistant bacterial strains, complete debridement, wound preparation and subsequent dressing of burn wounds |

| Stempel et al. (39) | Retrospective analysis | 15 cases; average age 60 (26 - 78)/high mortality rate | F. solani | NA | Systemic glucocorticoids/voriconazole, terbinafine, amphotericin |

| Pruskowski et al. (40) | Analytical | NA | Aspergillus spp., Mucor spp. | NA | Histopathological evaluation/tissue culture surgical management systemic antifungals amphotericin B triazole antifungals |

| Jabeen et al. (41) | Retrospective study | 19 cases | Fusarium spp., Aspergillus flavus | Tissue cultures | Broad-spectrum antibiotics; Stated that it is crucial to review culture protocols in burn patients for prevention and optimal patient management. |

| Branski et al. (42) | Retrospective study | 398 patient/burns > 40% TBSA | Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., and Fusarium spp. | NA | Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp., and various fungal strains lead to increasing mortality rate. |

| Atty et al. (43) | Case report | Male, 92% TBSA | Fusarium and Mucor spp. | NA | Debridement and grafting |

| Farooqiet al. (36) | Retrospective study | 140 cases | Fusarium spp. | Bacterial cultures | Tissue cultures in local settings, accurate diagnosis and treatment are urgently needed. |

| Young et al. (44) | Retrospective study | 18 patients/average age (38.4 ± 11.9 y)/TBSA (54.5 ± 23.4 percent) mortality 45 percent | Fusarium spp. | NA | Clinical characteristics of Fusarium isolated cases |

| Stoianovici et al. (45) | Retrospective study | median age 35 (32 - 41); 28% female; TBSA (55 ± 23%) mortality 45 percent | Fusarium spp. | Tissue cultures | The cause of death was infection with multisystem organ failure and sepsis, which occurred in 88% of cases. The use of prolonged mechanical ventilation and central venous catheterization is essential. Given the high mortality rate associated with Fusarium infection and the long time to antifungal susceptibility results, an appropriate empiric treatment strategy is emphasized. |

| Gonzalez et al. (46) | Retrospective study | Male (69.8%), and the median age (5 y); 22 patients (35.48%) died | F. solani; F. oxysporum; Aspergillus spp., | Biopsies of burn patients | Suspicion of Fusarium infection is essential for the appropriate treatment strategy for burn patients, including prompt initiation of antifungal therapy and wound debridement. Other appropriate strategies to reduce patient mortality include the development of a comprehensive protocol for the evaluation of burn patients, implementation of an early surgical approach, use of early molecular methods and markers, and timely administration of antifungal therapy. |

Abbreviations: Spp., species; IV, intravenous; TBSA, total body surface area.

5. Discussion

A burn wound provides an ideal environment for the growth and proliferation of microorganisms. The tissues within the burn wound are non-viable and lack blood vessels. Due to the absence of polymorphonuclear cells, antibodies, and systemic antibiotics, the conditions inside the wound create a favorable setting for the growth of bacteria and fungi, particularly Fusarium spp. (47-49). On the other hand, various strategies for preventing infections, particularly fungal infections resulting from burns, in hospital settings and across different patient groups are among the challenges that have garnered attention today, making effective prevention and treatment strategies for burn patients crucial (17, 50, 51).

The present study was conducted to achieve the objectives of the study, specifically to determine the mortality rate among burn patients with fungal infections caused by Fusarium spp., identify the media for Fusarium detection, explore the best treatment methods, and assess effective prevention and treatment strategies, as well as the percentage of burns and demographic information. Examining the first objective of the research, the mortality rate, the survey results indicate that the most reported cases of mortality were less than half of the sample population. In some instances, due to the large number of samples, the death rate reported was slightly higher (5, 29, 32, 44). Additionally, researchers have noted in various studies that early sample examinations have revealed that opportunistic fungi in the Fusarium spp. are clinically significant in burn wounds, leading to systemic infections and mortality in burn patients (11). A study sampling individual in the intensive care unit also demonstrated that twenty-four percent of patients with filamentous fungi succumbed, while fifty percent were infected with Fusarium spp. Furthermore, filamentous fungi have been observed in some cases among burn patients in Spain. Notably, about half of the patients who died were attributed to Fusarium spp., underscoring the necessity for rapid laboratory diagnosis of fungal infections among patients. Understanding the prevalence and type of fungus in each burn center facilitates the selection of the most appropriate experimental treatment (16).

In response to the second research question, findings showed that fungal infections identified by type of fungus are predominantly F. solani, an opportunistic fungus found in burn lesions. While antibiotic drug regimens effectively control bacterial infections, these opportunistic fungal infections should be tested histologically to rule out further involvement of the burn tissue. Conversely, the identification of molecules to discover spp. and drug tests should be employed to select the appropriate antifungal treatment (15).

Schaal et al. have shown that epidemiologically, Aspergillus fumigatus has the highest prevalence among burn patients compared to Fusarium, which exhibits a markedly different prevalence in Indian and North American countries (17). Additionally, several cases of burn patients with diabetes have been reported who had Fusarium infections. Fusarium osteomyelitis has been documented in diabetic patients across various regions, including developed countries such as the United States. In India, a sample of F. solani was identified in cases of Fusarium endophthalmitis among diabetic patients. In Turkey, Fusarium spp. were found to be one of the causes of diabetic foot wound infections (22, 33, 52-55). Therefore, it can be stated that fungal infections caused by Fusarium in diabetic groups should be considered, along with the presence of burn wounds as a risk factor for these infections.

Rosanova et al. (2016) believed their study was the first case of skin infection caused by an emerging fungus identified as an unusual pathogen (21). Evidence from other studies indicated that wound infections in burn patients represent a small percentage of fungal infections, with Neurospora sitophila types being found (26-28, 33). To identify the spp., the findings show that most samples for identifying Fusarium are taken from burnt tissue for biopsy diagnosis (15, 17, 21, 23, 24). Other findings revealed that the use of drugs such as amphotericin B and voriconazole has been suggested in several studies for treatment. The researchers also indicated that the development of antifungal medications is essential due to the existence of drug-resistant fungi (21, 23, 29).

Additionally, the analysis of relatively small burns in a young patient, as studied by Smolle et al., has demonstrated that appropriate infection control and prevention strategies — such as addressing additional trauma, managing wound infections with resistant bacterial strains, performing complete debridement, preparing wounds, applying subsequent dressings to burn wounds, administering renal replacement therapy, and implementing targeted antibiotic therapy along with early patient discharge — can be beneficial (38). Schaal et al.’s study underscores that systemic treatment with amphotericin B or sodium hypochlorite should also be administered in cases of simultaneous bacterial infections (17).

In reply to the fifth and sixth aims of the research, the review has shown that among the examined cases of total TBSA, the most reported cases were of considerable extent in the texts (12, 15, 29, 32). Moreover, men have more cases of Fusarium fungal infections than women (29, 30, 32, 43).

In response to another research objective, the analysis of strategies for preventing fungal infections in burns revealed that meticulous wound care and microbial surveillance were identified as two critical factors. Another study stated that, alongside careful wound care, clean and sterile techniques should be employed in burn patients to prevent fungal contamination (11). In the study by Schaal et al., three key prevention strategies were also emphasized, including environmental controls (high air exchange rates, over-pressurized operating rooms, etc.), the use of HEPA filtration and quiet airflow in surgical wards, and structural measures such as separate access points, individual rooms, closed doors/windows, and spatial separation of patients to reduce external contact (17). The results show that infection control practices have relied on factors such as strict aseptic techniques during dressing changes, the use of sterile gloves, masks, gowns, and caps, demarcation of work areas — especially during reconstruction — and the maintenance and proper functioning of protective devices (12, 14, 17). Ensuring minimal disruption during patient transport to reduce the risk of contamination has also been recommended as a strategic measure for monitoring infection (32). Some researchers have suggested that early radical debridement and wound closure are crucial to preventing infection. Empirical prophylactic drug therapy should be considered for those at high risk of invasive burn wound infection (23). Furthermore, early closure of burn wounds, frequent microbiological evaluation of burn wounds, and aggressive surgical debridement of burn wounds have been emphasized to prevent infection (25, 29). In burn patients resulting from accidents, contact with water or soil should be regarded as a potential pathogen and a promoter of infection to enhance prevention efforts (32, 36). Other studies have also indicated that reviewing culture protocols in burn patients is vital for prevention and optimal patient management (41).

5.1. Conclusions

Considering the identification of F. solani spp., particularly in men with burns and the associated high mortality rate, healthcare providers should prioritize early diagnosis and appropriate antifungal treatment as a key strategy for the future. Conversely, since Fusarium fungal infection leads to angioinvasion, especially in high-risk patients, diagnosis and treatment must be prioritized.

5.2. Limitation

The limitation of the study was access to the full text of some articles. To overcome this limitation, the research team tried to collect articles by contacting their authors or publishers.