1. Context

Health systems worldwide are increasingly challenged by the rising demand for quality healthcare services (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies four key dimensions of clinical service quality: Professional performance, resource efficiency, patient satisfaction, and risk management (2). Human resources represent a major cost in hospitals (3), and in sanctioned countries, consequences such as migration, brain drain, and economic collapse further strain health systems (4). Human resources for health (HRH) are a core component of effective health systems (5), essential for achieving universal health coverage (UHC) and the sustainable development goals (SDG) (6). In some countries, HRH training consumes over a quarter of the public budget (7). Yet, many lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) face persistent HRH shortages, leading to inequities and poor service quality (8), a problem intensified during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (9). To address these gaps, WHO launched the Global Strategy on HRH: Workforce 2030 (10), supported by regional frameworks like EMRO’s Action Plan (11).

Despite these efforts, EMRO countries still face severe workforce deficits (12), especially in conflict zones like Yemen and Afghanistan (13), with healthcare worker (HCW)-to-population ratios below WHO standards (14) and physician-to-nurse imbalances (15). In 2018, EMRO nations committed to UHC2030, emphasizing equitable and resilient systems (16). Achieving UHC requires sufficient, well-distributed, and skilled health workers (17). The WHO estimates a global shortfall of over 17 million HCWs by 2030, especially in rural areas (18). Ongoing conflicts in EMRO further destabilize fragile health infrastructures (19).

2. Objectives

This systematic review evaluates the implementation of the WHO Global Strategy for HRH: Workforce 2030 in LMICs within the EMRO. Specifically, it assesses progress toward the 2020 milestones in countries including Iran, Djibouti, Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia, Palestine, and Pakistan, and examines the effectiveness of interventions aimed at strengthening health workforce development (Table 1).

| Objectives | Milestones by 2020 |

|---|---|

| Objective 1: Optimizing performance, quality, and impact of the health workforce through evidence-informed policies on HRH, contributing to healthy lives and well-being, effective UHC, resilience, and strengthened health systems at all levels | 1.1. All countries will have established accreditation mechanisms for health training institutions. |

| Objective 3: Building the capacity of institutions at subnational, national, regional, and global levels for effective public policy stewardship, leadership, and governance of actions on HRH | 3.1. All countries will have inclusive institutional mechanisms in place to coordinate an intersectoral health workforce agenda. |

| 3.2. All countries will have an HRH unit with responsibility to develop and monitor policies and plans. | |

| 3.3. All countries will have regulatory mechanisms to promote patient safety and adequate oversight of the private sector | |

| Objective 4: Strengthening data on HRH to enhance monitoring and accountability of national and regional strategies, as well as the global strategy | 4.1. All countries will have made progress in establishing registries to track health workforce stock, education, distribution, flows, demand, capacity, and remuneration |

| 4.3. All countries will have made progress in sharing HRH data through national health workforce accounts and submitting core indicators to the WHO Secretariat annually | |

| 4.4. All bilateral and multilateral agencies will have strengthened health workforce assessment and information exchange |

Abbreviations: HRH, human resources for health; UHC, universal health coverage; WHO, World Health Organization.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This systematic review evaluated interventions supporting the implementation of the WHO Global Strategy for HRH: Workforce 2030 in seven EMRO countries classified as low- or middle-income by the World Bank: Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, and Tunisia. The review followed preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and applied a structured approach to synthesize relevant literature. Country selection was based on three criteria: Policy performance in implementing the global strategy, shared socioeconomic and health system challenges, and contextual diversity enabling comparative analysis.

3.2. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted across seven databases — PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Global Health, Health Systems Evidence (Beta), Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, and Cochrane Library — from January 15 to February 15, 2023, with an update extending to August 2025 (21). The search targeted peer-reviewed and grey literature published in English between January 2015 and August 2025. Boolean search strings were developed using three keyword categories: Workforce, strategy milestones, and country names (Appendices 1 and 2 in Supplementary File).

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they evaluated HRH interventions aligned with the WHO Global Strategy in EMRO LMICs. Eligible articles were peer-reviewed, published in English, and focused on programs, policies, or initiatives aimed at strengthening HRH. Exclusion criteria encompassed studies from high-income countries, regions outside EMRO, non-peer-reviewed sources, and those lacking direct relevance to Workforce 2030. Data extraction captured authorship, publication year, study design, intervention scope, target groups, outcomes, and alignment with strategic milestones. Reviewer responsibilities included screening, full-text evaluation, data extraction, synthesis, quality appraisal, and transparent documentation (Appendix 3 in Supplementary File).

3.4. Quality Assessment

Methodological quality was assessed using Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) appraisal tools (22). While randomized trials showed strong internal validity, cross-sectional designs and lack of control groups limited causal inference. Common biases included convenience sampling, inadequate blinding, and subjective reporting. The grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) framework was applied to evaluate evidence certainty (Appendices 4 and 5 in Supplementary File):

- High certainty: Accreditation mechanisms improved educational outcomes.

- Moderate certainty: Policy development showed promise in Tunisia and Morocco.

- Low certainty: Cross-sectional studies lacked causal clarity.

- Very low certainty: Self-reported data were prone to bias.

The findings underscore the need for more rigorous, methodologically sound studies to inform HRH policy-making in the region.

3.5. Protocol Registration

This review was not registered due to its limited scope, absence of institutional funding, and its focus on synthesizing regional policy literature. At the time of study initiation, registration was not mandated for reviews addressing health workforce governance in LMICs.

4. Results

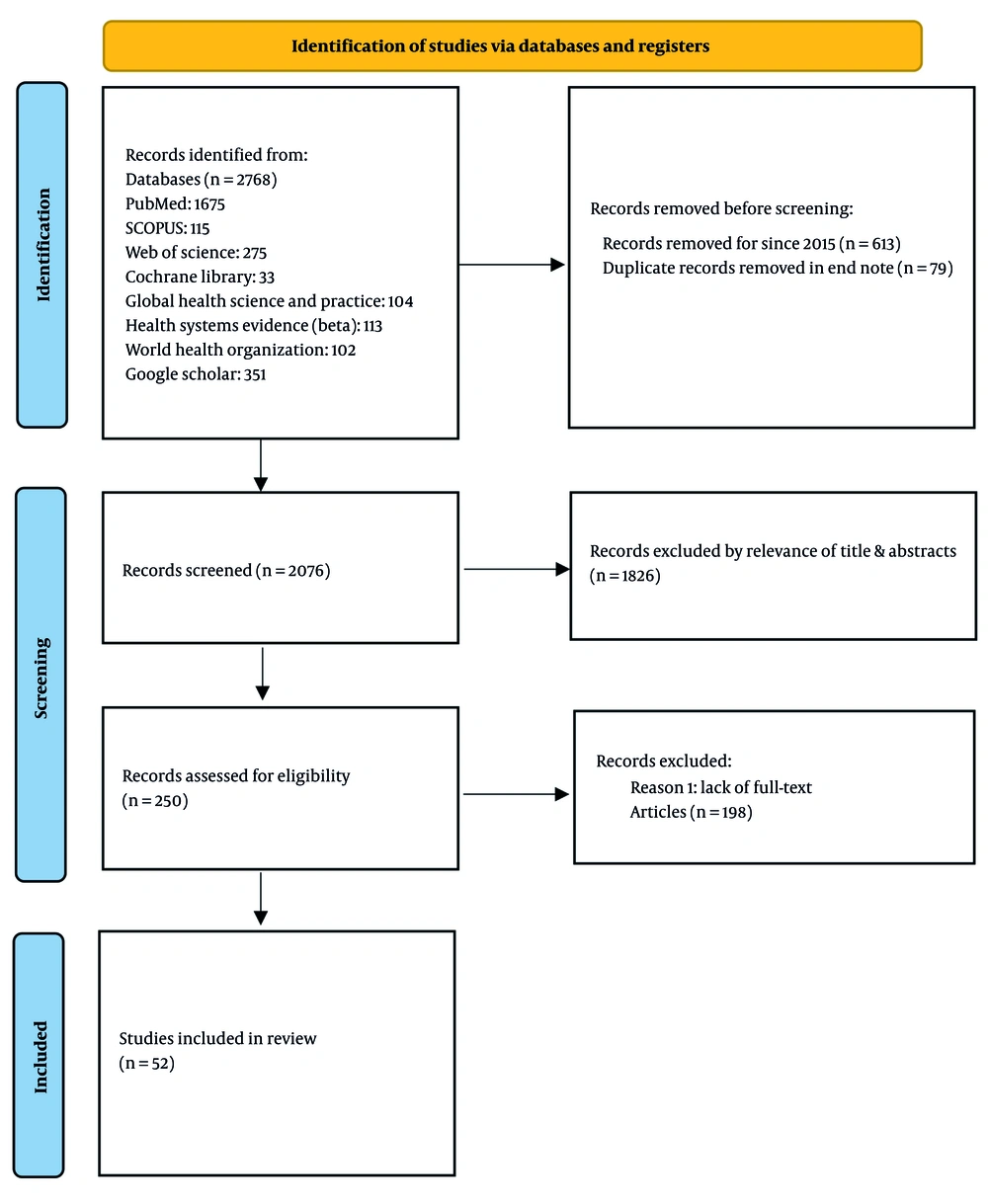

This systematic review examined the implementation of the WHO Global Strategy for HRH: Workforce 2030 in seven EMRO countries: Iran, Djibouti, Morocco, Egypt, Tunisia, Palestine, and Pakistan. From 2,768 records identified, 2,076 were screened after removing duplicates. A total of 52 studies were included for final analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) and Appendix 7 in Supplementary File detail the selection process.

4.1. Overview of Findings

The review identified key interventions contributing to health workforce development (Table 2 Appendix 6 in Supplementary File), including educational reforms, policy initiatives, and international collaborations. These efforts have led to measurable improvements in workforce capacity, competencies, and governance structures (Table 3).

| Authors | Year | Country | Method | Main Findings | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iqbal et al. (23) | 2022 | Eastern Mediterranean | Qualitative | Explored private sector engagement in health | Strengthen private sector involvement |

| Hameed et al. (24) | 2022 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Assessed mental health impact on HCWs | Enhance mental health support |

| Joudaki et al. (25) | 2015 | Iran | Data mining | Improved fraud detection in claims | Implement advanced data analytics |

| Hammoud et al. (26) | 2022 | Lebanon | Qualitative | Analyzed patient complaint systems | Establish effective complaint management |

| Safi-Keykaleh et al. (27) | 2022 | Iran | Grounded theory | Identified challenges in emergency decision-making | Train emergency medical technicians |

| Zeeshan et al. (28) | 2018 | Pakistan | Mixed methods | Identified public health education needs | Enhance public health curricula |

| Khosravi et al. (29) | 2021 | Iran | Qualitative | Assessed quality of midwifery care | Develop midwife-centered care models |

| Aghakhani and Baghaei (30) | 2020 | Iran | Quantitative | Family-centered model reduced post-dialysis fatigue | Implement family-centered care approaches |

| Rana et al. (31) | 2020 | Pakistan | Literature analysis | The HCWs face intense feelings of anxiety, fear, and helplessness in response to the COVID-19 pandemic | Create a structured model that integrates teams of Physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers to provide early psychological interventions to HCWs and patients |

| Ali et al. (32) | 2019 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Investigated barriers to TB treatment | Address barriers to treatment adherence |

| Hosseini Moghaddam et al. (33) | 2020 | Iran | Mixed methods | Analyzed patient transfer challenges | Improve transfer protocols |

| Chaudhary et al. (34) | 2020 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | Assessed PPE access during COVID-19 | Ensure adequate PPE supply |

| Doshmangir et al. (35) | 2020 | Iran | Qualitative | Explored healthcare service tariffs | Reform pricing strategies |

| Zaidi et al. (36) | 2020 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Examined community dynamics affecting nutrition uptake | Enhance community engagement |

| Mumtaz (37) | 2020 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Evaluated midwives' role in maternal health | Strengthen support for community midwives |

| Javed et al. (38) | 2019 | Pakistan | Mixed methods | Assessed patient satisfaction across sectors | Improve service quality |

| Basir et al. (39) | 2019 | Pakistan | Quantitative | Evaluated diagnostic accuracy for TB detection | Enhance diagnostic technologies |

| Mumtaz et al. (40) | 2015 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Identified success factors for community midwives | Scale successful midwifery practices |

| Sheikh et al. (41) | 2015 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Linked trust in health services to policies | Foster transparency in management |

| Khalil et al. (42) | 2018 | Egypt | Qualitative | Assessed gaps in HIV/HCV knowledge | Develop targeted training programs |

| Toure et al. (43) | 2021 | Palestine | Mixed methods | Evaluated HRH strategies for maternal health | Focus on training midwives and community workers |

| Mohammadpour et al. (44) | 2023 | Iran | Qualitative | Identified eight themes for the paradigm shift in Iran's healthcare, including the need for enhanced electronic health infrastructure and evidence-based decision-making | Implement reforms in e-health, pandemic budgeting, and support for HCWs |

| Ferrinho et al. (45) | 2022 | Djibouti | Qualitative | The COVID-19 pandemic exposed inadequacies in HRH leadership, highlighting the need for adaptive and participatory approaches | Develop effective HRH leadership to navigate complex health labor market dynamics |

| Faruk et al. (46) | 2021 | Palestine | Mixed methods | Analyzed HRH management barriers | Develop strategies to overcome barriers |

| Alawode, et al. (47) | 2025 | Iran | Quantitative | Assessed HRH distribution impact | Improve equitable distribution of workers |

| G. B. D. Human Resources for Health Collaborators et al. (48) | 2023 | Tunisia | Qualitative | Explored HRH's role in universal coverage | Strengthen HRH policies for universal coverage |

| Alkhaldi, et al. (49) | 2024 | Palestine | Mixed methods | Revealed strengths in HRH training initiatives | Enhance training based on local needs |

| Zare et al. (50) | 2021 | Iran | Qualitative | Analyzed HRH strategies during COVID-19 | Adapt HRH strategies to evolving needs |

| El-Jardali et al. (51) | 2015 | Eastern Mediterranean | Institutional | Emphasized support for health policy research | Foster research institutions for policy development |

| Zhang (52) | 2015 | Egypt | Mixed methods | Assessed HRH challenges in Egypt | Develop targeted HRH improvement interventions |

| Charfi et al. (53) | 2023 | Tunisia | Cross-sectional | Increased human resources development of child psychiatry improved treatment access | Enhance training for non-specialists incentivize psychiatrists in underserved areas increase accessibility to services strengthen community-based services promote public awareness and stigma reduction |

| Habib et al.(54) | 2020 | Lebanon | Cross-sectional study | Poor self-rated health poor mental health chronic illness musculoskeletal pain | Improve working conditions address job satisfaction support for chronic illness and mental health job security initiatives policy advocacy community engagement |

| Al Hassani et al. (55) | 2024 | Morocco | Quantitative | Assessed HRH challenges in rural healthcare | Strengthen rural HRH initiatives |

| Kasemy et al. (56) | 2020 | Egypt | Qualitative | Prevalence of workaholism mental health outcomes quality of life critical specialty HCWs predictors of burnout | Address personal characteristics supportive work environment regular health assessments mental health resources promote team collaboration training on time management awareness campaigns encourage breaks and downtime |

| Najjar et al. (57) | 2022 | Palestine | Mixed methods | Analyzed HRH policies' impact on accessibility | Revise HRH policies for equitable healthcare |

| Zhila et al. (58) | 2022 | Iran | Quantitative | Assessed HRH workforce planning in health needs | Implement dynamic workforce planning models |

| Mir et al. (59) | 2015 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional study | Willingness to leave service geographical factors dissatisfaction with performance evaluation dissatisfaction with salary influence of local politicians | Public healthcare system can improve staff retention, enhance job satisfaction, and ultimately provide better healthcare services to the population |

| Norris et al. (60) | 2022 | Various | Qualitative | Evaluated the African Health Initiative’s role | Promote embedded implementation research |

| Akhlaq et al. (61) | 2020 | International | Qualitative | Identified barriers to health information exchange | Address barriers to improve information exchange |

| Alikhani and Damari (62) | 2017 | Iran | Qualitative | Proposed a partnership model for health screening | Implement partnership strategies for screening |

| Al-Mandhari et al. (63) | 2019 | Eastern Mediterranean | Qualitative | Explored multi-sectoral action on health for SDGs | Foster collaboration across sectors |

| Moucheraud et al. (64) | 2016 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Identified barriers to maternal and child health | Address community perceptions to improve access |

| Irfan et al. (65) | 2015 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Analyzed public sector provider challenges | Improve working conditions for healthcare staff |

| Mumtaz et al. (66) | 2015 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Identified gaps in the community midwife program | Strengthen midwife training and support |

| Rafique et al. (67) | 2015 | Pakistan | Survey | Assessed dengue knowledge among providers | Enhance training on dengue management |

| Shah et al. (68) | 2021 | Pakistan | Cost-effectiveness | Analyzed cost-effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination | Promote vaccination programs |

| Hameed et al. (24) | 2022 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Documented HCWs' pandemic experiences | Provide ongoing support for HCWs |

| Siebert and Souto-Galvan (69) | 2024 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Explored barriers to mental health service access | Increase awareness to reduce stigma |

| Shahbaz et al. (70) | 2022 | Pakistan | Qualitative | Identified obstacles to anaesthesiology practice | Improve training for anaesthesiologists |

| Ben Romdhane et al. (71) | 2015 | Tunisia | Qualitative | Examined challenges related to non-communicable diseases | Strengthen health policies for NCD management |

| Aly et al. (72) | 2021 | Egypt | Qualitative | Highlighted occupational stressors in healthcare | Address stress through supportive measures |

| Shaikh (73) | 2015 | Pakistan | Descriptive and analytical study | Growth of the private sector challenges of quality and cos lack of effective oversight consumer trust potential for collaboration need for reforms | Strengthening regulatory frameworks enhancing public-private partnerships improving quality of care increasing accessibility promoting health education investing in workforce development |

Abbreviations: HCW, healthcare worker; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HRH, human resources for health; SDGs, sustainable development goals.

| Countries | Challenges | Key Interventions | Achievements | Milestones | SDGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Djibouti | Limited healthcare infrastructure and workforce shortages | HRH response protocols and training initiatives | Improved healthcare access and emergency response | Milestone 1.1: Enhanced healthcare response systems | Goal 3: Good health and well-being |

| Iran | Disparities in workforce distribution and mental health resources | Data-driven workforce planning and mental health training | Better resource distribution and mental health services | Milestones 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3: Enhanced HRH training | - |

| Egypt | Challenges in service delivery and workforce morale | Training programs and policy reforms for HRH improvement | Increased workforce morale and service delivery | Milestones 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3: Improved HRH policies | - |

| Morocco | Inequities in rural healthcare access | Community health programs to boost HCW presence | Enhanced rural healthcare access and service quality | Milestones 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3: Rural health initiatives | - |

| Tunisia | Need for better coordination in health services | Emergency management protocols and multi-sector collaboration | Improved coordination and emergency preparedness | Milestones 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3: Enhanced stakeholder coordination | - |

| Palestine | Challenges in HRH management | Tailored training for midwives and CHWs | Strengthened HRH capabilities and training | Milestones 4.1 and 4.2: Enhanced training programs | - |

| Pakistan | Barriers to healthcare delivery, stigma, and misinformation | Awareness campaigns and mental health training for providers | Increased mental health awareness and service provision | Milestones 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3: Improved mental health training | - |

Abbreviations: SDGs, sustainable development goals; HRH, human resources for health; HCW, healthcare worker; CHWs, community health workers.

4.2. Effectiveness of Interventions

- Educational reforms: Updated curricula and practical training approaches increased the number and readiness of healthcare professionals.

- Policy development: Inclusive policy-making strengthened system responsiveness, particularly where stakeholder engagement was prioritized.

- International collaboration: Cross-border partnerships facilitated knowledge exchange and adoption of best practices.

4.3. Impact on Workforce Development

- Growth: Recruitment and training expanded workforce numbers, though rural shortages persist.

- Competency enhancement: Training programs improved clinical skills and service delivery.

- Challenges: Retention, uneven distribution, and limited continuing education remain barriers.

4.4. Strategic Objectives Assessed

Progress was evaluated across four strategic domains:

- Accreditation: Efforts to improve education quality in training institutions.

- Policy implementation: Varying success in developing and executing HRH policies.

- Institutional governance: Establishment of HRH units for workforce oversight.

- Data systems: Advances in registry development, though data sharing remains limited.

4.5. Country-Specific Highlights

- Iran: Workforce distribution challenges persist.

- Djibouti: The HRH gaps evident during health emergencies.

- Morocco: Training programs improved service delivery.

- Egypt: Distribution issues hindered access to care.

- Tunisia: The HRH central to UHC advancement.

- Palestine: Conflict-related barriers to HRH management.

- Pakistan: Mental health concerns among HCWs noted.

Search strategy flow chart preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA): Consider, if feasible, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools (74).

5. Discussion

This systematic review analyzed 52 studies (2015 - 2025) to evaluate HRH interventions in EMRO LMICs, focusing on workforce availability, training, policy implementation, and the role of community health workers (CHWs). Quantitative data revealed disparities in workforce distribution, while qualitative findings provided stakeholder perspectives on implementation challenges and opportunities. Significant progress was observed in accreditation mechanisms, particularly in Egypt and Jordan, aligning with WHO milestone 1.1 (20, 75). Egypt’s robust systems improved training quality and workforce readiness, with similar efforts reported in Morocco (76) and sub-Saharan Africa (77). These reforms underscore the importance of investing in education to build a competent health workforce capable of meeting evolving health needs (78).

The CHWs emerged as key contributors to service delivery, especially in rural areas. Iran’s integration of CHWs demonstrated improved access and outcomes (79-81), supporting WHO milestone 3.1. Evidence from other regions confirmed their impact on maternal and child health, primary care, and mortality reduction (82-84). Empowering CHWs is essential for advancing UHC and promoting equity, particularly where formal infrastructure is limited.

Despite these gains, workforce distribution and retention remain critical challenges. Countries like Djibouti and Pakistan face shortages in underserved areas (85, 86), with urban preference among professionals exacerbating disparities (9, 85-87). Studies from Ethiopia further highlight resource constraints and high turnover in rural settings (88). Addressing these gaps is vital for fulfilling UHC2030 and SDG 10 commitments.

Stakeholder engagement proved pivotal in successful HRH policy implementation. Collaborative approaches involving governments, academic institutions, and communities enhanced program relevance and sustainability. Community involvement in CHW deployment fostered trust and utilization (81), while participatory planning in Egypt improved long-term outcomes (85). Strengthening such partnerships is crucial for responsive and adaptable health systems.

5.1. Conclusions

This review assessed the implementation of the WHO Global Strategy for HRH: Workforce 2030 in selected EMRO LMICs. While progress in accreditation and education is evident, persistent challenges in workforce distribution and retention hinder equitable service delivery. Advancing SDG 3 and UHC requires targeted investment, improved monitoring, and coordinated policy action. Continued research and stakeholder collaboration are essential to strengthen HRH systems across the region.

5.2. Policy Implications

Standardized accreditation and regional coordination can elevate health education across EMRO. Policies supporting CHW training, deployment, and retention — backed by financial and social incentives — are essential. To attract professionals to underserved areas, strategies must include career development, infrastructure investment, and supportive work environments. Public-private partnerships and community engagement frameworks should be prioritized. Aligning HRH policies with SDG targets on equity and access remains fundamental.

5.3. Study Limitations

- Design limitations: The predominance of cross-sectional studies limits causal inference.

- Publication bias: Positive findings may overrepresent intervention success.

- Regional specificity: The EMRO-focused data may not be generalizable.

- Data variability: Inconsistent definitions and collection methods hinder synthesis.

- Temporal scope: Post-COVID-19 trends may be underrepresented.

- Stakeholder bias: Limited patient perspectives due to reliance on provider-reported data.

- Implementation gaps: Barriers to strategy execution were insufficiently explored.

- Language restriction: Exclusion of non-english studies may omit relevant evidence.