1. Background

Welding is a metallurgical process involving the joining of metals through the application of pressure, heat, flame, or an electric arc. It is considered one of the most essential technical skills, playing a pivotal role in industrial development across various sectors (1). However, welding operations expose workers to a wide range of occupational hazards, both physical and chemical. These include, but are not limited to, welding fumes and gases, thermal stress, excessive noise, non-ionizing radiation, poor ergonomic conditions, and numerous safety risks. Prolonged exposure to such factors poses serious threats to workers’ health, particularly in terms of respiratory function and exposure to hazardous physical agents (2, 3).

Welding fumes and gases have been linked to a variety of adverse health outcomes, including pulmonary, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, and dermatological disorders. Notably, exposure may impair glomerular filtration, thereby increasing the risk of chronic kidney disease, and may also disrupt hepatic and biliary system function (4, 5). According to National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), welders are approximately 40% more likely than the general population to develop occupation-related lung cancer (6). Studies reveal that long-term exposure to welding environments has been significantly associated with an increased prevalence of noise-induced hearing loss in workers with over a decade of experience, as well as epithelial cell alterations contributing to respiratory conditions such as asthma and acute bronchial irritation. The mitigation of occupational injuries and the attainment of comprehensive safety and health standards in welding operations necessitate that workers possess a thorough understanding of the welding process, including the identification of occupational hazards and the correct application of personal protective equipment (PPE) at each stage of the task (7). This informed awareness enables welders to adhere to standardized safety protocols, ensuring the appropriate use of protective equipment to minimize exposure to harmful agents and preserve their health and safety during work activities (8). While the primary responsibility for compliance with safety measures rests with the workers themselves, empirical observations indicate that many welders do not fully adhere to established safety guidelines. This non-compliance manifests in various forms, including failure to utilize PPE, incorrect usage of protective gear, neglect of workplace conditions, and disregard for safety recommendations. Such behavior significantly elevates the risk of occupational incidents and injuries (9-11).

Considering the critical role of PPE in ensuring occupational safety during welding operations, an important question arises: Should PPE be employed exclusively during active welding, when the welder is directly operating the torch and exposed to intense radiation and fumes, or is its use also warranted during ancillary tasks within the welding workflow? In practice, many welders limit PPE usage to periods of direct welding, despite the fact that other operational phases, such as transporting tools and materials, inspecting structural components to identify welding sites, and managing inter-weld intervals to prevent structural deformation, can similarly involve exposure to hazardous agents. These overlooked phases may still present significant risks due to the presence of residual fumes, ergonomic strain, or indirect exposure to welding by-products.

Although numerous studies have documented the adverse effects of welding hazards such as noise, metal fumes, and chemical exposures, the majority of these investigations have focused primarily on the direct welding phase. However, in real industrial environments, workers are also exposed to residual fumes, indirect noise, and ergonomic strains during ancillary tasks such as equipment transportation, preparation, and post-welding cleanup. These overlooked phases have rarely been systematically analyzed in relation to the continuous and appropriate use of PPE. The novelty of the present study lies in the application of hierarchical task analysis (HTA) to decompose welding and related tasks and to propose a decision-making framework for selecting PPE not only during active welding but also throughout all stages of work. This approach addresses an important research gap and provides evidence-based strategies to enhance occupational safety in welding industries.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to design a decision-making system based on HTA to support the selection of appropriate PPE across all stages of welding activities within the metal structure fabrication industry.

3. Methods

This applied research adopts a descriptive-analytical approach design and was conducted in 2023 at Sepahan Mapna Metal Equipment Manufacturing Industry, located in Isfahan province. The facility produces large metal structures, including air intake systems, combustion chambers, compressor units, and turbines. Welding is a critical process, affecting both structural integrity and product quality. An example of the welding operations within this industry is presented in Figure 1.

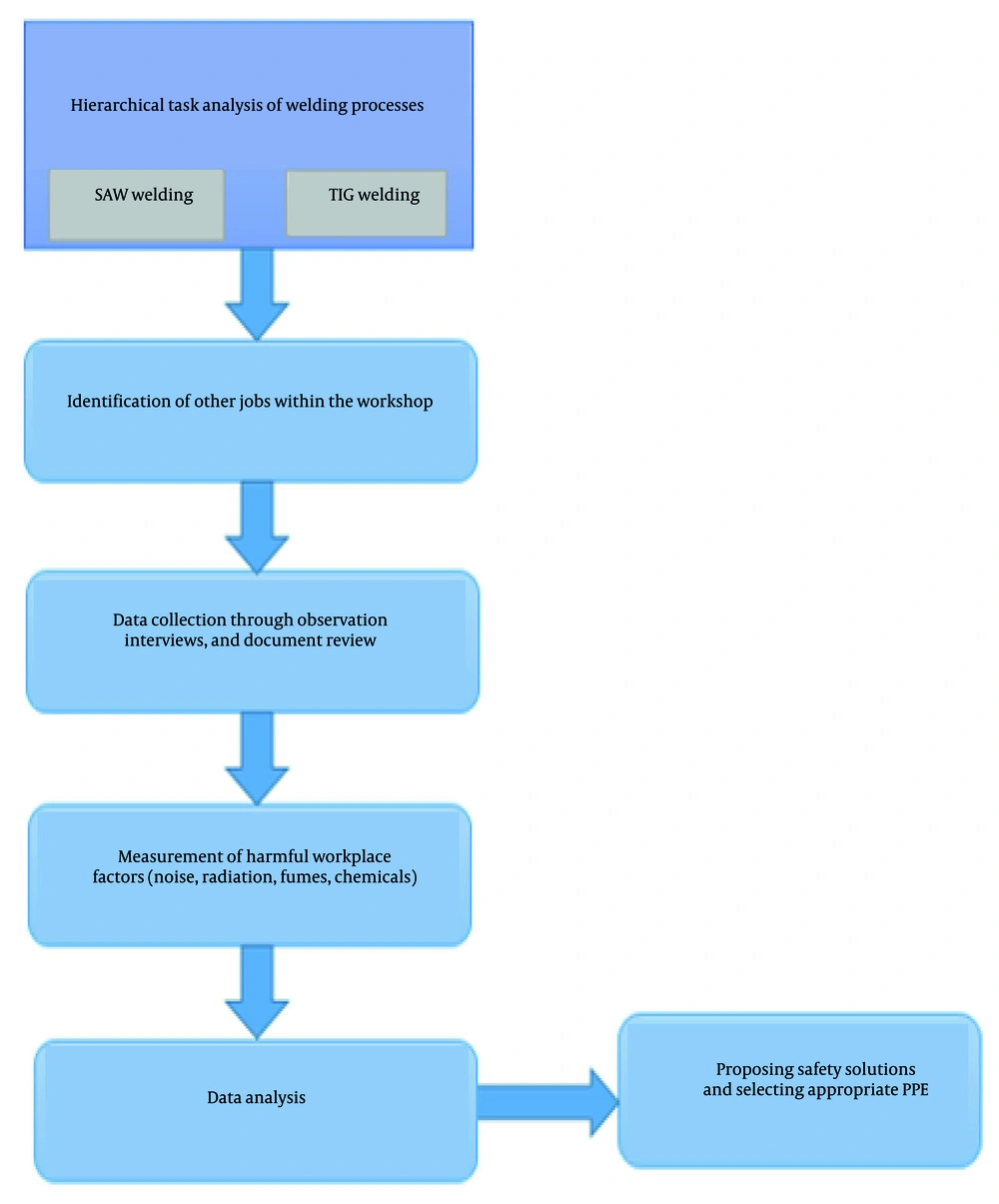

The aim of this study is to develop a decision-making system based on HTA for the optimal selection of PPE in welding processes. To achieve this, the study was carried out in three integrated phases, combining both qualitative techniques (observations, interviews, and document analysis) and quantitative environmental measurements. This mixed-methods approach ensured a systematic and evidence-based evaluation of workplace hazards rather than relying solely on simple observation.

3.1. Identification of Welding Work Processes

The HTA was applied to systematically analyze welding procedures, breaking down tasks and subtasks. Data were collected through a triangulated approach, including direct observations of welding activities, semi-structured interviews with professional welders, critical analysis of operational manuals, and examination of official job descriptions. Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic coding to identify key tasks, sub-tasks, and potential hazard points. The HTA provides a structured framework that links human actions to system requirements, enabling task standardization, identification of critical points, and reduction of human error in complex industrial operations (12).

3.2. Analysis of Workshop Occupational Roles

The spatial and functional organization of workshop roles was assessed, focusing on interactions among workers, their proximity to welding stations, and exposure to welding operations. Physical boundaries, workflow patterns, and the distribution of contaminants were examined to provide context for indirect exposure risks, occupational safety considerations, and optimization of task sequencing within the workshop environment.

3.3. Assessment of Environmental Hazards

Quantitative measurements from 2023 were systematically reviewed and analyzed, including light intensity, radiation levels, noise, and airborne pollutants. Quantitative data were processed using descriptive statistical methods in Excel to calculate exposure levels and identify critical risk factors. These data enabled a precise assessment of occupational exposure levels, identification of critical risk factors, and informed the selection of targeted PPE. A schematic overview of the methodology, integrating qualitative observations and quantitative environmental assessment, is presented in Figure 2.

4. Results

4.1. Task Decomposition of Welding Processes

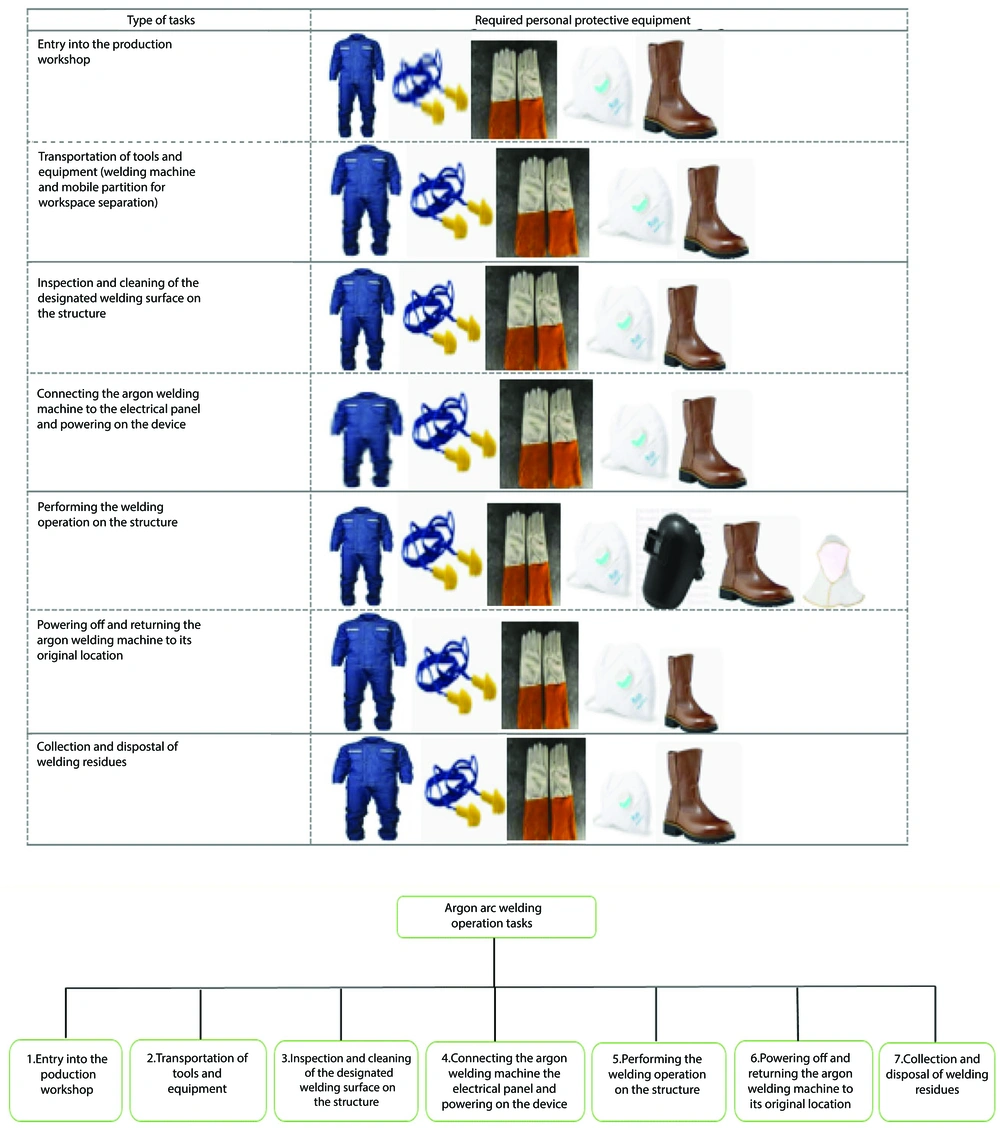

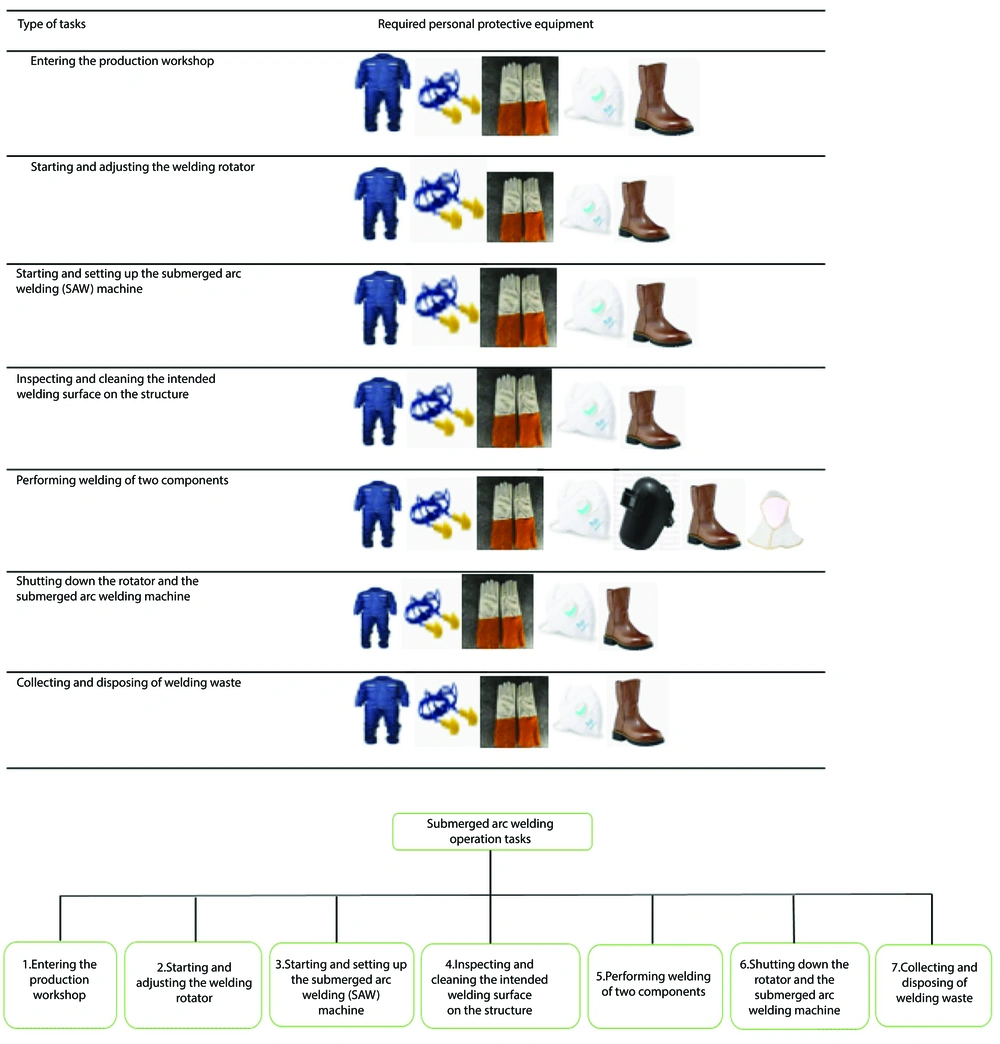

The HTA was applied to both argon arc welding (TIG) and submerged arc welding (SAW) to systematically decompose the workflow into discrete tasks and subtasks. Both welding processes consist of seven core tasks, spanning from workshop entry to the collection and disposal of welding residues. Baseline PPE, including workwear, safety boots, respirators, hearing protection, and gloves, is required throughout all stages, with additional protection such as a welding helmet and flame-resistant hood during active welding to mitigate ultraviolet (UV)/infrared (IR) radiation, molten metal, and fume hazards. Figure 3 presents the detailed HTA framework for TIG, including task descriptions and corresponding PPE. Similarly, Figure 4 provides the task breakdown and PPE requirements for SAW operations. This structured analysis identifies critical stages requiring strict adherence to safety protocols to ensure worker protection, procedural accuracy, and operational efficiency.

4.2. Workshop Organization and Occupational Roles

The production workshops at Sepahan MAPNA Industries are divided into five interconnected sections (A1 - A5), each responsible for a distinct phase of structural manufacturing. Workers perform collaborative tasks across fabrication, assembly, and welding operations, resulting in potential indirect exposure to hazards from adjacent processes.

4.3. Assessment of Environmental Hazards

Workers in the workshops are exposed to multiple environmental hazards, including noise, chemical pollutants, and non-ionizing radiation. Noise levels for welders averaged 91.2 dB over 7 to 9 hours, exceeding recommended limits. While concentrations of nickel, iron oxide, lead, and aluminum were within permissible limits, elevated levels of manganese and crystalline silica were observed, posing respiratory risks. The UV and IR radiation measurements were within safe limits. Table 1 summarizes these environmental hazards, highlighting the critical importance of the continuous use of hearing protection, respiratory masks, and other PPE to mitigate occupational risks.

| Industrial Pollution | Sources |

|---|---|

| Noise | Hammering and sledgehammering |

| Welding and gouging operations | |

| Cutting and grinding using angle grinders | |

| Impact of metal components with the ground or with each other | |

| Operational noise from machinery such as CNC machines, lathes, guillotines, punching machines, and radial drills | |

| Use of compressed air for cleaning machines | |

| Movement and transport of machinery and forklifts within the workshop | |

| Non-ionizing radiation | Welding: UV |

| Welding and cutting: IR | |

| Chemical pollutants | Particulates (fumes): Welding (iron, nickel, chromium, lead, manganese, aluminum, cobalt, cadmium, beryllium, copper, and tin) |

| Particulates (mists): Machining and cutting (Z1 oil) | |

| Metallic particulates: Metallic particulates (crystalline silica) |

Abbreviations: UV, ultraviolet; IR, infrared.

5. Discussion

In this study, HTA was applied to systematically examine the processes of TIG and SAW, allowing for the identification of discrete operational steps and task-specific requirements. Both methods share core tasks, including workshop entry, equipment setup, workpiece preparation, execution of welding operations, and post-process cleanup. However, notable operational differences were observed, particularly regarding the use of specialized equipment such as the SAW machine and the rotator fixture. These distinctions highlight the importance of tailoring safety measures to the unique demands of each welding method. The proper use of PPE emerged as a critical requirement across both welding methods. Baseline PPE, including workwear, safety shoes, gloves, respirators, and hearing protection, was essential across all stages, while specialized PPE such as welding helmets and flame-resistant hoods was indispensable during active welding. Recent studies confirm that consistent and correct use of PPE substantially reduces respiratory and dermal risks in welding environments (13, 14).

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of PPE is significantly enhanced when combined with engineering controls such as localized exhaust ventilation systems, noise-dampening barriers, and management controls like task rotation. The absence of such controls in the studied workshops contributed to higher levels of exposure. Evidence from other industrial settings shows that the integration of engineering and management controls alongside PPE use can significantly reduce occupational exposure to noise and airborne contaminants. For instance, Ejaz et al. demonstrated that localized exhaust systems effectively remove contaminants, thereby improving worker safety (15). Additionally, Tan et al. found that engineering noise control strategies, including the use of noise barriers and equipment modifications, significantly mitigate noise exposure in industrial environments (16).

Occupational roles within the workshops were highly interdependent, with workers operating concurrently in shared spaces, leading to cross-exposure to hazards beyond their immediate tasks. For example, welders positioned near grinding operations were exposed not only to welding fumes and arc radiation but also to metallic dust and sparks from adjacent activities. Such secondary exposures increase risks of eye injuries, respiratory irritation, and dermatological conditions, findings consistent with recent studies that documented similar multi-source exposure risks in metalworking industries (17).

The assessment of environmental hazards indicated that chemical exposure and noise pollution were the most significant risks. Welding fumes contained toxic metals, including Pb, Ni, Cr, Cd, Mn, Al, and Co, capable of causing acute respiratory irritation and chronic pulmonary diseases. Grinding operations released respirable crystalline silica, potentially inducing silicosis, while oil mist aerosols were identified as irritants with potential long-term carcinogenic effects. Noise exposure averaged 91.2 dB for welders over 7 - 9 hours, exceeding permissible exposure limits and carrying significant risks of hearing loss and neurological impacts. Prior studies corroborate that welding processes, particularly when combined with secondary tasks such as grinding and cutting, frequently generate airborne contaminants and hazardous noise exceeding occupational safety standards (18, 19). Collectively, noise exposure, welding fumes, and hazards associated with shared work activities were identified as the most critical risks in this study.

From a practical perspective, these findings hold direct implications for occupational and environmental health and safety (OEHS) professionals. Beyond enforcing consistent PPE use, OEHS practitioners should prioritize the implementation of engineering controls such as localized exhaust ventilation, adopt management measures such as task rotation and workflow optimization, and ensure comprehensive worker training programs to enhance hazard awareness and compliance. Routine health monitoring, including periodic audiometric testing and respiratory evaluations, should also be incorporated to detect early signs of occupational disease and guide preventive interventions.

Finally, a limitation of this study is that only HTA was employed to evaluate welding processes. While HTA provided a structured breakdown of tasks and hazards, complementary human error analysis methods such as the systematic human error reduction and prediction approach (SHERPA), technique for human error prediction (THERP), and human error assessment and reduction technique (HEART) were not applied. Incorporating these tools in future research would allow a more comprehensive evaluation of error pathways and provide opportunities to compare identified risks with the adequacy of existing protective measures. Although this study focused on TIG and SAW welding techniques, future investigations should include other common methods such as gas metal arc welding (GMAW) and shielded metal arc welding (SMAW). Comparative analyses would allow more detailed identification of task-specific hazards and safety requirements, enabling tailored protective measures for each technique. Incorporating behavioral assessment methods, such as safe behavior sampling (SBS), alongside injury and accident data analysis, could further enhance understanding of compliance with PPE protocols and reveal recurring risk patterns.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that welding procedures vary considerably depending on the welding technique, each presenting unique technical and safety requirements. Occupational hazards in welding workshops, including chemical pollutants, airborne particulates, noise, and non-ionizing radiation, pose significant risks to worker health. The interdependent nature of occupational roles increases the likelihood of secondary exposure to these hazards. Consistent and correct use of PPE remains a fundamental strategy for risk mitigation. Furthermore, the integration of engineering controls, management measures such as task rotation, and worker training is essential to enhance occupational safety. Future investigations should expand to include other welding methods and incorporate behavioral assessments to better understand compliance with safety protocols. Overall, strict adherence to safety standards, continuous monitoring, and targeted interventions are critical for protecting workers and promoting a safe industrial environment.