1. Background

Childhood cancer represents a significant global public health challenge and is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children and adolescents (1). With approximately 291.3 thousand new cases and 98.8 thousand deaths worldwide in 2019, its impact is substantial (2). In Iran, childhood malignancies, particularly leukemia and solid tumors, contribute significantly to this health burden, reflecting yet also differing from global trends in incidence and presentation (1, 3). Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common pediatric cancer in Iran, but regional variations suggest the influence of local genetic, environmental, and sociodemographic factors (1, 4).

The etiology of most childhood cancers, including leukemia and solid tumors, remains incompletely understood and is considered multifactorial (5-7). While a few risk factors like ionizing radiation are well-established (8, 9), the complex interplay of genetic susceptibility, early-life exposures, and socioeconomic conditions is increasingly recognized. Sociodemographic factors such as parental education, socioeconomic status (SES), and urban residency can critically influence both cancer risk and outcomes, often by affecting access to care and exposure to environmental hazards (10, 11). Furthermore, the unique sociodemographic and cultural context of Iran provides a critical setting for this research. This includes specific factors such as regional patterns of younger maternal age at first birth, relatively high rates of consanguineous marriages which may influence genetic susceptibility (12), and rapid urbanization leading to distinct environmental exposures, such as the significant air pollution in Tehran (13-15). Investigating these population-specific characteristics is essential to understanding the global picture of childhood cancer etiology.

In parallel, a growing body of evidence highlights the potential role of specific perinatal and environmental exposures. Factors such as prenatal parental smoking, high birth weight, birth order, and maternal age have been investigated for their links to leukemia (16-20). Similarly, environmental challenges associated with urbanization and industrialization, including exposure to traffic-related air pollution and hazardous chemicals, have been proposed as contributors to cancer risk, though findings are often inconsistent across different populations (13-15). This inconsistency underscores the necessity for research within specific regional contexts to account for unique genetic backgrounds and lifestyle factors.

Given Iran's significant socioeconomic transformation, urbanization, and environmental changes over recent decades, a detailed investigation into the risk factors for childhood cancer within this population is urgently needed.

2. Objectives

This 10-year hospital-based case-control study aims to identify the key sociodemographic and environmental determinants associated with childhood leukemia and solid tumors in Iranian children. A specific aim was to investigate the role of less commonly quantified prenatal exposures, such as perceived maternal psychological stress and exposure to household chemicals via painting, within this unique context. The findings from this study are expected to provide critical, context-specific insights to inform targeted prevention strategies and guide the development of tailored public health interventions within Iran's healthcare system.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Setting

This case-control study was conducted at Ali-Asghar Children’s Hospital, a major pediatric referral center in Tehran, Iran, affiliated with Iran University of Medical Sciences. The hospital serves a diverse patient population from across Iran and internationally. The study spanned a 10-year period from 2013 to 2023, encompassing both case and control groups.

Cases comprised all children under 18 years of age diagnosed with leukemia or solid tumors (retinoblastoma, neuroblastoma, hepatoblastoma, Wilms tumor, medulloblastoma, germ cell tumors, or thyroid carcinoma) during the study period at Ali-Asghar Children’s Hospital. The control group consisted of children formally admitted as inpatients to the same hospital for non-oncologic reasons within the same timeframe. This specifically included inpatient children admitted to different departments. Patients who were treated and discharged directly from the emergency ward were not eligible as controls.

The use of hospital-based controls was chosen for practical reasons and because they share a similar referral pattern and geographic catchment area as the cases, making them a comparable population for this setting. Controls were selected from a broad range of inpatient departments, including general pediatrics, infectious diseases, surgery, orthopedics, and otorhinolaryngology, to create a heterogeneous group representative of the general pediatric inpatient population without cancer. To ensure the control group was representative of a "healthy" population in terms of the exposures under investigation, we excluded children admitted for conditions that might share risk factors with childhood cancers. These exclusions included:

-Chronic diseases with potential environmental or genetic links (e.g., congenital heart disease, genetic syndromes, autoimmune disorders).

-Conditions directly related to parental occupational exposures (e.g., specific poisonings).

-Premature infants admitted to the NICU for prolonged stays.

For each case, one control was selected. Controls were randomly chosen using computer-generated random numbers from the hospital’s admission lists of eligible non-oncologic patients. Eligible controls were then approached and recruited for participation in the study.

3.2. Control Selection Process

Controls were selected from children formally admitted as inpatients to the same hospital for non-oncologic reasons during the study period. To ensure methodological rigor and comparable healthcare-seeking behavior, our sampling frame was explicitly restricted to the hospital's inpatient admission lists; children treated solely in the emergency department or outpatient clinics were not eligible. From this inpatient population, we randomly selected one control for each case using computer-generated random numbers. To create a representative sample of the general pediatric population without cancer and to minimize confounding, controls were drawn from a broad range of inpatient departments (e.g., general pediatrics, infectious diseases, surgery) and were excluded if they had chronic diseases, genetic syndromes, or conditions with potential environmental or genetic links to cancer.

3.3. Inclusion Criteria

Participants were included in the study if they met the following criteria:

-Age less than 18 years

-For cases: Confirmed diagnosis of leukemia or solid tumor by histopathology, morphology, and flow cytometry

-For controls: Admission for an acute, non-chronic condition (e.g., acute appendicitis, minor trauma, non-chronic infectious diseases like pneumonia)

Power consideration: The sample size was determined by the total number of eligible cases presenting during the study period. While we captured all available solid tumor cases (n = 30) over the decade, this sample size inherently limits the statistical power for this subgroup. Therefore, the analysis for solid tumors should be interpreted as exploratory and descriptive.

Power analysis: A post-hoc power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 software to quantify the statistical power for the solid tumor subgroup. Given the available 30 solid tumor cases and 114 controls, with an alpha of 0.05 and assuming a small-to-medium effect size (odds ratio = 1.8 - 2.0), the study achieved approximately 35 - 45% power for detecting associations with solid tumors. For the leukemia group (84 cases, 114 controls), under the same conditions, the study achieved 70 - 80% power. These calculations confirm that while the study was adequately powered for leukemia analyses, the solid tumor subgroup was underpowered to detect anything but very large effect sizes, supporting the exploratory interpretation of these results

3.4. Exclusion Criteria

These Participants were excluded:

For cases: The patient had died prior to recruitment. This decision was made for ethical considerations, to avoid causing distress to bereaved families, and due to concerns about the reliability of retrospectively collected exposure data from grieving parents.

For controls: A diagnosis of any chronic illness, genetic syndrome, or condition with a known or suspected environmental etiology that could plausibly be linked to the exposure variables under study (as listed in section 2.1).

3.5. Data Collection

Data were collected by trained healthcare staff under the direct supervision of the principal investigator. A structured, custom-designed checklist was used to systematically gather information during face-to-face or telephone interviews with one parent or guardian of each participant. Interviews were conducted in a quiet, controlled hospital environment to minimize distractions and ensure the quality of the data.

The Data Entry/Data Extraction Form captured the following variables:

-Demographic factors: Age, gender, birth weight, parental age, and parental education level

-Environmental and lifestyle factors: Parental occupational exposures (e.g., chemicals, electromagnetic fields, ionizing radiation), maternal obstetric history (including delivery method), infant feeding practices, parental smoking, and proximity of residence to industrial facilities.

All participants’ parents or guardians received detailed explanations regarding the study’s objectives, protocols, and potential implications before enrollment. The principal investigator provided ongoing oversight to ensure strict adherence to study protocols and to maintain the integrity of data collection.

3.6. Exposure Assessment

Data on environmental and lifestyle exposures were collected via parental report using a structured questionnaire. It is critical to note that variables such as 'house painting during pregnancy', 'proximity to a power pole,' and 'history of severe psychological stress' were operationalized as binary (yes/no) indicators based on parental perception and recall. To improve consistency in reporting, specific thresholds were used as prompts during the interviews: Exposure to house painting was defined as lasting for more than 10 days; proximity to a power pole was defined as living within an estimated 500-meter radius; and severe stress was explicitly defined as stemming from a major traumatic event such as bereavement or marital separation.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were described as counts (N) and percentages (%), as well as means with standard deviations (SD). The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was employed to assess the relationship between categorical variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was utilized to check the normality assumption for continuous variables. An ANOVA test was conducted to compare continuous variables across groups.

The dependent variable for this analysis was polytomous, comprising three mutually exclusive categories: Control, leukemia, and solid tumor. To examine the relationship between predictor variables and cancer type, we employed multinomial logistic regression, conducting both univariable and multivariable analyses. This technique was selected in preference to performing separate binary logistic regressions, as it allows for the simultaneous estimation of all relative risk ratios using a common referent category (the control group) within a single, coherent statistical framework. A key advantage of this approach is its superior statistical efficiency. Furthermore, it enables direct comparisons of coefficient estimates, thereby permitting an explicit evaluation of how specific risk factors differentially associate with the odds of a leukemia diagnosis relative to a solid tumor diagnosis.

Prior to finalizing the multivariable model, multi-collinearity between the independent variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). A VIF value of 10 is often taken as an indicator of severe multi-collinearity, while a value above 5 may suggest moderate correlation. In our final model, all VIF values were below 3, indicating that multi-collinearity was not a significant concern and that the parameter estimates are stable. The VIF values were calculated for all variables in the final model; the maximum VIF was 1.87, indicating no evidence of multicollinearity.

Variables showing a P-value < 0.25 in univariable analysis were included in the initial multivariable multinomial logistic regression model. This liberal threshold is recommended to avoid excluding variables that may be important contributors in the multivariable context (21). In addition to this statistical screening, variables considered to be theoretically important confounders based on existing literature (e.g., maternal age, child’s sex, and birth weight) were assessed for inclusion in the multivariable model regardless of their statistical significance in univariable analysis (22).

The assumptions for the multinomial logistic regression were satisfied. Statistical significance was established for adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a two-tailed P-value < 0.05. Data analysis was conducted with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Given the limited sample size for the solid tumor subgroup, a post-hoc power analysis was performed using G*Power 3.1. This analysis indicated that with 30 solid tumor cases and 114 controls, the study had approximately 35 - 45% power to detect a small-to-medium effect size (AORs = 1.8 - 2.0) at α = 0.05. This confirms the exploratory nature of the analysis for solid tumors and underscores that the study was only powered to detect very large effect sizes for this outcome.

3.8. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Research Ethical Review of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1399.504). The researcher obtained written informed consent from parents or guardians and assured them of confidentiality. All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

This study included 228 children (leukemia = 84, solid tumor = 30, control = 114). Table 1 presents the detailed sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants, including a case group (N = 114) and a control group (N = 114), drawn from Ali Asghar Children's Hospital over a 10-year period from 2013 to 2023.

| Characteristics | Total (N = 228) | Control (N = 114) | Leukemia (N = 84) | Solid Tumor (N = 30) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child's age at diagnosis/admission (mo) | 77.07 ± 43.61 | 78.51 ± 40.61 | 75.74 ± 47.85 | 75.37 ± 43.47 | 0.884 |

| Mother age at delivery (y) | 27.56 ± 5.59 | 26.14 ± 6.36 | 29.74 ± 5.21 | 26.87 ± 5.72 | < 0.001 c |

| Birth weight (g) | 3100 ± 499 | 2920 ± 457 | 3320 ± 486 | 3160 ± 429 | < 0.001 c |

| Sex | 0.858 | ||||

| Male | 117 (51.3) | 59 (51.8) | 44 (52.4) | 14 (46.7) | |

| Female | 111 (48.7) | 55 (48.2) | 40 (47.6) | 16 (53.3) | |

| Mother's education level | 0.016 c | ||||

| < Diploma | 56 (24.6) | 34 (29.8) | 15 (17.9) | 7 (23.3) | |

| Diploma | 86 (37.7) | 49 (43.0) | 26 (31.0) | 11 (36.7) | |

| > Diploma | 86 (37.7) | 31 (27.2) | 43 (51.2) | 12 (40.0) | |

| Father's education level | 0.662 | ||||

| < Diploma | 61 (26.8) | 32 (28.1) | 21 (25.0) | 8 (26.7) | |

| Diploma | 81 (35.5) | 44 (38.6) | 26 (31.0) | 11 (36.7) | |

| > Diploma | 86 (37.7) | 38 (33.3) | 37 (44.0) | 11 (36.7) | |

| Mother's occupation | 0.497 | ||||

| Housekeeper | 177 (77.6) | 85 (74.6) | 67 (79.8) | 25 (83.3) | |

| Employed | 51 (22.4) | 29 (25.4) | 17 (20.2) | 5 (16.7) | |

| History of cancer in first-degree family | 11 (4.8) | 5 (4.4) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0.808 |

| History of cancer in second-degree family | 73 (32.0) | 35 (30.7) | 28 (33.3) | 10 (33.3) | 0.894 |

| Father's tobacco use during pregnancy | 72 (31.6) | 41 (36.0) | 20 (23.8) | 11 (36.7) | 0.159 |

| Pregnancy using assisted reproductive techniques | 7 (3.1) | 1 (0.9) | 6 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.024 c |

| Breastfeeding | 215 (94.3) | 106 (93.0) | 81 (96.4) | 28 (93.3) | 0.596 |

| Breastfeeding period | 0.016 c | ||||

| 0 month | 13 (5.7) | 8 (7.0) | 3 (3.6) | 2 (6.7) | |

| Less than 6 months | 22 (9.6) | 5 (4.4) | 16 (19.0) | 1 (3.3) | |

| 6 -12 months | 17 (7.5) | 7 (6.1) | 8 (9.5) | 2 (6.7) | |

| More than 12 months | 176 (77.2) | 94 (82.5) | 57 (67.9) | 25 (83.3) | |

| Cesarean delivery | 150 (65.8) | 77 (67.5) | 55 (65.5) | 18 (60.0) | 0.738 |

| Parity | 0.095 | ||||

| Nullipara | 122 (53.5) | 69 (60.5) | 38 (45.2) | 15 (50.0) | |

| Multipara | 106 (46.5) | 45 (39.5) | 46 (54.8) | 15 (50.0) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b P-values for continuous variables were derived from ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests, P-values for categorical variables were derived from chi-square or Fisher's exact tests.

c P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4.2. Environmental Factors

As detailed in Table 2, several environmental exposures during pregnancy were significantly more common among cases than controls. A history of house painting was reported for 9.5% of leukemia and 10% of solid tumor cases, compared to only 1.8% of controls (P = 0.037). Furthermore, a history of severe maternal stress was markedly more prevalent in both the leukemia (33.3%) and solid tumor (50%) groups than in the control group (13.2%; P < 0.001).

| Characteristics | Total (N = 228) | Control Group (N = 114) | Leukemia (N = 84) | Solid Tumor (N = 30) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House painting during pregnancy | 13 (5.7) | 2 (1.8) | 8 (9.5) | 3 (10) | 0.037 b |

| Closeness of the home to the manufactory | 25 (11) | 16 (14) | 5 (6) | 4 (13.3) | 0.189 |

| Living near a power pole during pregnancy | 30 (13.2) | 15 (13.2) | 10 (11.9) | 5 (16.7) | 0.803 |

| Living near a power pole after pregnancy | 36 (15.8) | 17 (14.9) | 14 (16.7) | 5 (16.7) | 0.936 |

| History of severe stress during pregnancy | 58 (25.4) | 15 (13.2) | 28 (33.3) | 15 (50) | < 0.001 b |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b P < 0.05 was considered as a statistically significant level.

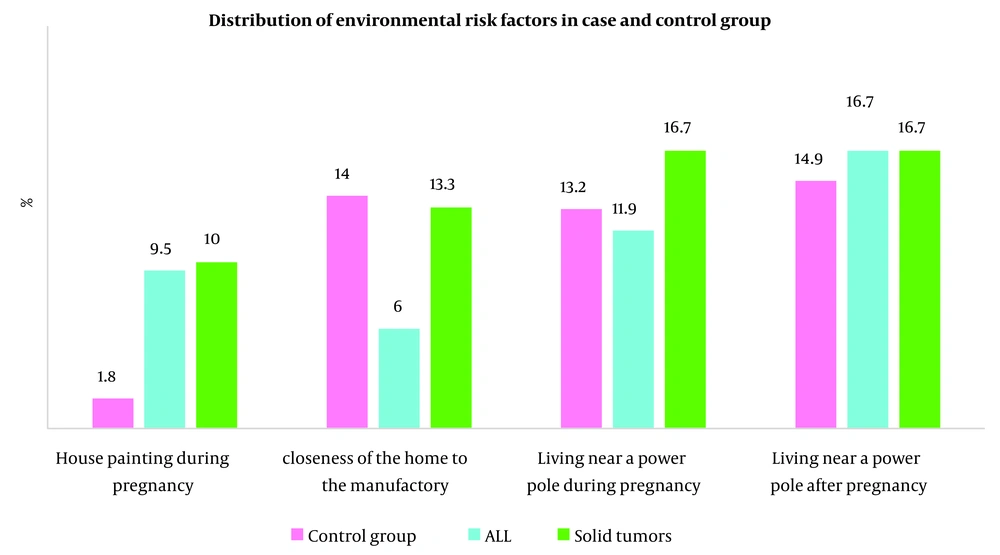

4.3. Distribution of Environmental Risk Factors Across Leukemia, Solid Tumor, and Control Groups

The distribution of environmental risk factors, such as house painting during pregnancy, proximity of the home to manufacturing facilities, and living near a power pole both during and after pregnancy, is illustrated in Figure 1.

4.4. Association Between Risk Factors and Cancer (Leukemia and Solid Tumor)

The associations of risk factors and cancer (leukemia and solid tumor) are shown in Table 3.

| Characteristics | Leukemia VS Controls | Solid Tumor VS Controls | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 a | Model 2 b | Model 1 a | Model 2 b | |||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | P-Value c | OR | 95% CI | P-Value c | OR | 95% CI | P-Value c | OR | 95% CI | P-Value c | |

| Mother age at delivery ≥ 35 y (Ref: < 35 y) | 3.36 | 1.37 - 8.22 | 0.008 | 3.45 | 1.30 - 9.09 | 0.012 | 1.47 | 0.37 - 8.22 | 0.586 | 1.54 | 0.37 - 6.68 | 0.560 |

| Mother's education levels, > diploma | 0.32 | 0.15 - 0.68 | 0.003 | 0.35 | 0.15 - 0.80 | 0.013 | 0.53 | 0.19 - 1.52 | 0.240 | 0.54 | 0.18 - 1.63 | 0.275 |

| Father's education levels, > diploma | 0.67 | 0.33 - 1.37 | 0.278 | - | - | - | 0.86 | 0.31 - 2.41 | 0.864 | - | - | - |

| Mother's occupation, employed | 1.35 | 0.68 - 2.65 | 0.393 | - | - | - | 1.71 | 0.6 - 4.89 | 0.318 | - | - | - |

| Birth weight (g), < 2500 | 4 | 1.3 - 12.24 | 0.015 | 3.18 | 0.97 - 10.44 | 0.056 | 1.8 | 0.5 - 6.54 | 0.372 | 1.74 | 0.45 - 6.73 | 0.421 |

| History of cancer in the first-degree family | 1.38 | 0.39-4.93 | 0.620 | - | - | - | 0.75 | 0.08-6.68 | 0.798 | - | - | - |

| History of cancer in a second-degree family | 1.15 | 0.628 - 2.10 | 0.652 | - | - | - | 1.13 | 0.479 - 2.66 | 0.782 | - | - | - |

| Father's tobacco use while mother was pregnant | 1.8 | 0.96 - 3.38 | 0.070 | 1.06 | 0.52 - 2.14 | 0.874 | 0.97 | 0.42 - 2.24 | 0.943 | 0.76 | 0.31 - 1.88 | 0.55 |

| Cesarean delivery | 1.1 | 0.60 - 1.99 | 0.760 | - | - | - | 1.39 | 0.61 - 3.2 | 0.440 | - | - | - |

| Breastfeeding | 2.04 | 0.52 - 7.92 | 0.308 | - | - | - | 1.06 | 0.21 -5.26 | 0.946 | |||

| Closeness of the home to the manufactory | 2.55 | 0.9 - 7.26 | 0.080 | 2.25 | 0.75 - 6.73 | 0.148 | 1.06 | 0.33 - 3.45 | 0.921 | 1.12 | 0.33 - 3.78 | 0.857 |

| Living near a power pole during pregnancy | 1.12 | 0.48 - 2.64 | 0.790 | - | - | - | 0.76 | 0.25 - 2.28 | 0.622 | - | - | - |

| Living near a power pole after pregnancy | 1.14 | 0.528 - 2.47 | 0.741 | - | - | - | 1.14 | 0.384 - 3.39 | 0.812 | - | - | - |

a Model 1: Without adjustment.

b Model 2: Adjustment for all variables remaining in the final model.

c P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant level.

4.4.1. Leukemia

The results of the multinomial logistic regression for leukemia are presented in Table 3. In the unadjusted analysis (model 1), advanced maternal age (≥ 35 years vs. < 35 years) (COR = 3.36, 95% CI: 1.37 - 8.22) and low birth weight (COR = 4.0, 95% CI: 1.3 - 12.24) were significant risk factors.

In the multivariable model adjusted for key covariates (model 2), higher maternal education level (> diploma) emerged as a significant protective factor, associated with a 65% reduction in the odds of leukemia (AOR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.15 - 0.80). Conversely, maternal age ≥ 35 years (AOR = 3.45, 95% CI: 1.30 - 9.09; reference: < 35 years) was associated with significantly higher odds of leukemia. It is noteworthy that the association for low birth weight, while substantial, lost statistical significance after adjustment (AOR = 3.18, 95% CI: 0.97 - 10.44, P = 0.056).

4.4.2. Solid Tumor

As shown in Table 3, the analysis for solid tumors revealed no statistically significant associations in either the univariable (model 1) or multivariable (model 2) analyses. For example, in the adjusted model, the point estimate for maternal age ≥ 35 was elevated but not statistically significant (AOR = 1.54, 95% CI: 0.37 - 6.68), and maternal education showed a non-significant protective trend (AOR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.18 - 1.63). The lack of significant findings is likely attributable to the limited sample size of the solid tumor group (n = 30).

5. Discussion

Leukemia and solid tumors in children represent distinct categories of pediatric cancers with differing origins, risk factors, and clinical characteristics (23). This case-control study, set in the understudied Iranian population, examined a range of sociodemographic and environmental risk factors for both cancers simultaneously. Our results confirm the importance of maternal age and education for leukemia risk in this context and highlight several prenatal environmental exposures that warrant further investigation. While significant associations were identified for leukemia, no statistically significant risk factors were found for solid tumors, a finding likely attributable to the limited sample size for this subgroup.

The unique context of our study population merits emphasis. Conducted in Tehran, a metropolis with documented challenges of air pollution and rapid industrialization, our research captures exposures relevant to many developing urban centers. Furthermore, we explicitly investigated psychosocial factors, such as severe maternal stress during pregnancy, which remains an understudied area in pediatric oncology, particularly in the Middle East. While our assessment was based on recall, the strong univariate association observed (P < 0.001) suggests that the role of prenatal stress, potentially amplified by sociocultural pressures, warrants further investigation with more precise instruments. Although data on consanguinity was not available for this cohort, its prevalence in the region underscores the importance of future research integrating genetic susceptibility with environmental exposure data.

5.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

There is a complex association between SES and the risk of childhood leukemia and solid tumors (24). The complex relationship between SES and childhood cancer risk is evident in our findings. We found that a lower maternal education level was significantly associated with increased odds of childhood leukemia, consistent with studies suggesting that higher parental education can reduce risk (24, 25), though this association can vary by population and study design (26). This replication of a protective effect in our unique context underscores its potential universal importance.

Furthermore, our study reinforces the established link between advanced maternal age (≥ 35 years) and an increased odd of childhood leukemia, particularly ALL, as supported by large meta-analyses (19, 20). The observed variations across studies likely stem from differences in populations, cultures, and lifestyles. Notably, other sociodemographic factors such as parental occupation and breastfeeding history did not show significant associations with either cancer type, suggesting a more pronounced role for maternal age and education in leukemia etiology within this cohort.

5.2. Environmental Risk Factors

Our investigation into perinatal exposures revealed that reported house painting during pregnancy and severe maternal stress were significantly more prevalent among cases in univariate analysis. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence on the potential influence of environmental and psychosocial factors (13, 14). The results revealed that house painting during pregnancy was significantly more frequent in the leukemia and solid tumor groups, and severe stress during pregnancy was reported by a notably higher proportion of mothers in the cancer groups, solid tumors (P < 0.001). Heck et al. showed that prenatal exposure to traffic-related pollutants (e.g., nitrogen oxides) during the first trimester increases ALL risk (8). Also, Ghosh et al. showed that a 25-ppb rise in nitric oxide during pregnancy correlates with a 9% - 23% higher ALL odds (14).

Our study points to the potential role of indoor sources of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Similarly, the strong association with severe maternal stress, though based on retrospective recall, highlights an understudied area in pediatric oncology, particularly in the Middle East, and warrants investigation with more precise, biomarker-based instruments.

It is critical to interpret these environmental findings with caution. The subjective and non-quantified nature of these exposure variables means that the observed associations are hypothesis-generating. Future studies must prioritize objective exposure metrics to clarify these complex relationships and move from correlation toward causation.

5.3. Strengths and Limitations

This case-control study, conducted over 10 years at a major pediatric referral center in Tehran, benefits from several key strengths. It utilized a well-defined case group with confirmed diagnoses and randomly selected hospital controls, which helped ensure diagnostic accuracy and similar referral patterns. The systematic collection of comprehensive demographics, environmental, and lifestyle data was achieved through a structured checklist administered by trained staff under strict supervision.

However, the findings must be interpreted in the context of several important limitations.

First, the retrospective assessment of exposures is susceptible to recall bias. Parents of children with cancer may recall and report past exposures differently and more thoroughly than parents of children in the control group. This is particularly relevant for subjective measures. To mitigate this, we used a standardized questionnaire for all participants and selected a hospital-based control group whose parents might also be more likely to scrutinize past exposures. Nonetheless, the potential for differential recall remains.

Second, another significant limitation is the non-quantified and subjective nature of key exposure variables. Although we provided operational definitions and thresholds (e.g., 10-day painting duration, 500-meter proximity), these measures ultimately relied on parental recall and perception without objective validation. This inherent misclassification would most likely bias the effect estimates towards the null. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating.

Third, the exclusion of deceased patients could have introduced survival bias. By excluding cases who had died prior to recruitment, our study sample may not be representative of all childhood cancer patients, particularly those with more aggressive diseases. If the risk factors under investigation are also associated with survival, the associations we observed may not accurately reflect those present at diagnosis.

Fourth, the single-center design affects the generalizability of our findings. As a major referral center, Ali-Asghar Children's Hospital admits children with more severe or complex conditions. Consequently, both our case and control groups may reflect specific subsets of the population, and our results may not be fully generalizable to the broader population of Iran or to other settings.

Finally, the study faced issues of limited statistical power. As detailed in the statistical analysis section, a post-hoc power analysis confirmed the study had low power (35 - 45%) to detect anything but very large effect sizes for the solid tumor subgroup (n = 30). Consequently, the non-significant findings for solid tumors should be interpreted as inconclusive rather than as definitive evidence of no association, and this analysis must be considered exploratory. This underpowered analysis means we were likely unable to detect true associations for solid tumors, and the non-significant results for this group should be interpreted as inconclusive rather than as evidence of no association.

5.4. Conclusions

This study identifies and highlights the critical importance of lower maternal education and advanced maternal age as significant risk factors for childhood leukemia in the Iranian population, aligning with findings from various international studies. Low birth weight also showed a strong, albeit borderline, association. In contrast, no significant risk factors were identified for solid tumors, a result that is likely due to the limited statistical power from the small sample size in this subgroup and potentially reflects the more elusive etiology of solid tumors globally. Environmental exposures such as house painting during pregnancy — a source of indoor chemical exposure that is of growing international concern — and severe maternal stress also appear to increase leukemia risk.

These results emphasize the significance of maternal education and perinatal health in childhood leukemia risk. Improving maternal education and reducing prenatal exposure to harmful chemicals and severe stress through public health initiatives may help decrease the incidence of leukemia. The role of these exposures in solid tumors remains uncertain and requires larger, multicenter studies. The stark difference in findings between leukemia and solid tumors underscores that they are distinct disease entities with different risk profiles. Future research must integrate objective exposure measurements with genetic data to better understand the complex interplay of environmental and biological factors in childhood cancer etiology.

These results translate into several clear public health implications and actionable recommendations:

-Enhance maternal and prenatal education: Public health initiatives should prioritize improving access to education for girls and women. Furthermore, integrating specific modules on childhood cancer risk factors into existing prenatal care and counseling programs is crucial. These modules should educate expectant parents about the potential risks associated with advanced maternal age, the importance of achieving a healthy birth weight, and the benefits of maternal education.

-Implement targeted prenatal counseling: Healthcare providers should offer tailored counseling to pregnant women, especially those of advanced maternal age. This counseling should emphasize the importance of adherence to prenatal care to mitigate risks and promote healthy fetal development.

-Reduce harmful environmental exposures: Public health guidelines should explicitly advise pregnant women to minimize exposure to VOCs. This includes recommending against participating in house painting or renovation activities during pregnancy and ensuring adequate ventilation when such activities are unavoidable. Clear labeling on paint products about risks during pregnancy could reinforce this message.

-Promote prenatal mental health: The strong association with severe maternal stress underscores the need to incorporate psychosocial support and stress management into routine prenatal care. This could involve screening for significant stress, providing resources for mental health support, and promoting stress-reduction techniques.