Fulltext

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a common hepatotropic RNA virus, which has been estimated to infect about 170 million people worldwide (1). The HCV infection progresses to chronicity in nearly 80% of cases, and chronic hepatitis C (CHC) infection is associated with the development of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplantation and associated complications in Western countries (2).

Differences in CHC prevalence, clinical profile and histological severity between different ethnic groups suggested a genetic contribution (3). Thus, in earlier candidate gene studies, several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within host genes and gene regions coding for the human leukocyte system, keratin, or coagulation factors were shown to be associated with progression of HCV-induced liver fibrosis (4). Among these, an independent genome-wide association study that identified a non-synonymous sequence variation (rs738409 C > G), encoding an isoleucine-to-methionine substitution at position 148 in the adiponutrin/patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) gene, has recently attracted much interest (5).

The G allele of the rs738409 variant leads to triglyceride (TG) accumulation in hepatocytes. Steatosis can promote inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress and has been shown to favor hepatocyte apoptosis in CHC (6). Steatosis is also closely associated with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance, a well-established cause of fibrosis progression in hepatitis C (7). The association of steatosis and CHC has been well described, and shown to occur in up to 66% of cases (6, 8). Steatosis accelerates the progression of CHC and is independently associated with stage III/IV hepatic fibrosis (8).

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have also been reported to be associated not only with elevated liver enzymes in healthy subjects, but also with disease severity, portal inflammation, lobular inflammation, steatosis, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (9). More recently, the G allele of the rs738409 variant has been reported to be associated with the occurrence of CHC (10). In view of the uncertain association of the I148M variant of PNPLA3 in CHC, we conducted a meta-analysis to comprehensively assess the overall performance of the I148M variant of PNPLA3 for the presence of CHC, and to analyze the heterogeneity between available studies before its wide application in clinical practice. The aim of this study was to evaluate the association of the I148M variant of PNPLA3 and the presence of CHC across various populations.

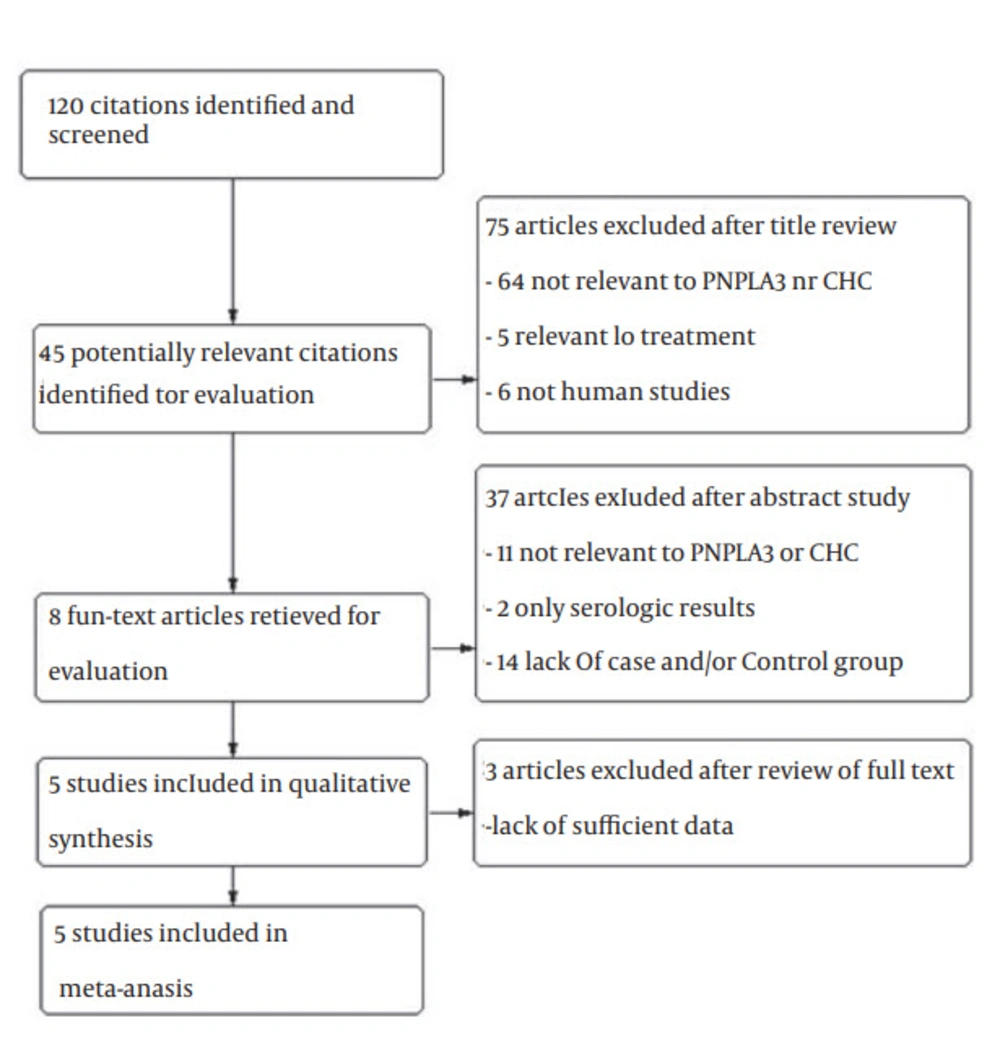

A total of 120 studies were retrieved based on the described search strategies. Eight eligible studies were identified for evaluation. Ultimately, three studies were excluded for having insufficient data. Thus, our final dataset for the meta-analysis (Figure 1) included five studies (14-18). The main features of the studies, included in the meta-analysis, are shown in Table 1. The genotype distributions of rs738409 polymorphism of PNPLA3 among included studies are shown in Table 2. A total of 2535 subjects were included (1692 patients and 843 healthy controls). Two of these studies were conducted in Italy (15, 17), and one in Bonn and Berlin (14), Japan (16) and Morocco (18). All of the five studies were hospital-based case-control studies (14-18). Information about liver biopsies was available for four studies (14-17). Hepatitis C Virus genotyping was performed using the TaqMan assay in three studies (15, 16, 18). All studies scored well in terms of adequate descriptions of selection criteria and availability of clinical data.

| First Author, Y | Ref. | Number of Patients | CHC | Controls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CG | GG | CC | CG | GG | |||

| Nischalke et al. 2011 | (14) | 352 | 85 | 64 | 13 | 112 | 69 | 9 |

| Valenti et al. 2011 | (15) | 998 | 424 | 310 | 85 | 118 | 56 | 5 |

| Miyashita et al. 2012 | (16) | 305 | 68 | 104 | 48 | 23 | 51 | 11 |

| Valenti et al. 2012 | (17) | 518 | 133 | 103 | 25 | 146 | 95 | 16 |

| Ezzikouri et al. 2014 | (18) | 362 | 90 | 106 | 34 | 66 | 54 | 12 |

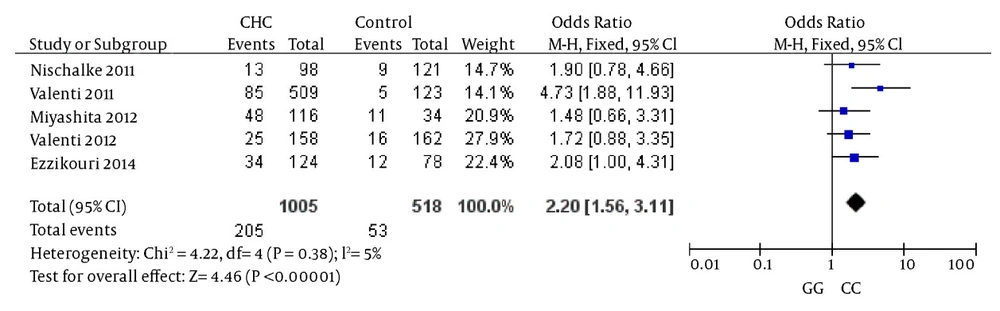

The comparison between cases and controls showed that CHC was significantly associated with the GG genotype. In the meta-analysis, the overall frequency of the GG genotype distribution was 20.4% (205/1005) in CHC, and 10.23% (53/518) in controls. The heterogeneity test indicated that the variation of trial-specific ORs was not statistically significant (χ2 = 4.22, P = 0.38); the fixed-effect method was used to combine the results. The combined OR was 2.20 (95% CI: 1.56 - 3.11) and was statistically significant (P < 0.00001). In the sensitivity analysis, the exclusion of individual studies did not change this significant result. Statistics calculated for studies assessing the association between gene polymorphisms of PNPLA3 and CHC when comparing homozygous GG and homozygous CC, are shown in the forest plot (Figure 2).

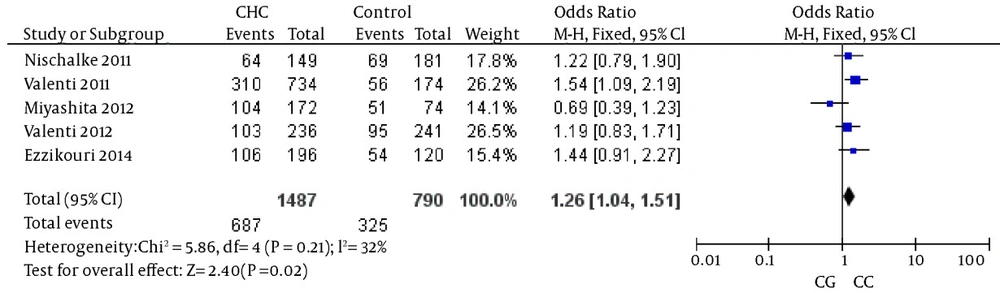

The analysis of the heterozygosity for the variant showed that CHC was significantly associated with the rs738409 G allele when the reference heterozygous CG was compared with homozygous CC, again suggesting an additive genetic effect (details in Figure 3). The heterogeneity test indicated that the variation of trial-specific ORs was not statistically significant (χ2 = 5.86, P = 0.21); the fixed-effect method was used to combine the results. The combined OR was 1.26 (95% CI: 1.04 - 1.51) and was statistically significant (P = 0.02). In the sensitivity analysis, the exclusion of individual studies did not change this significant result.

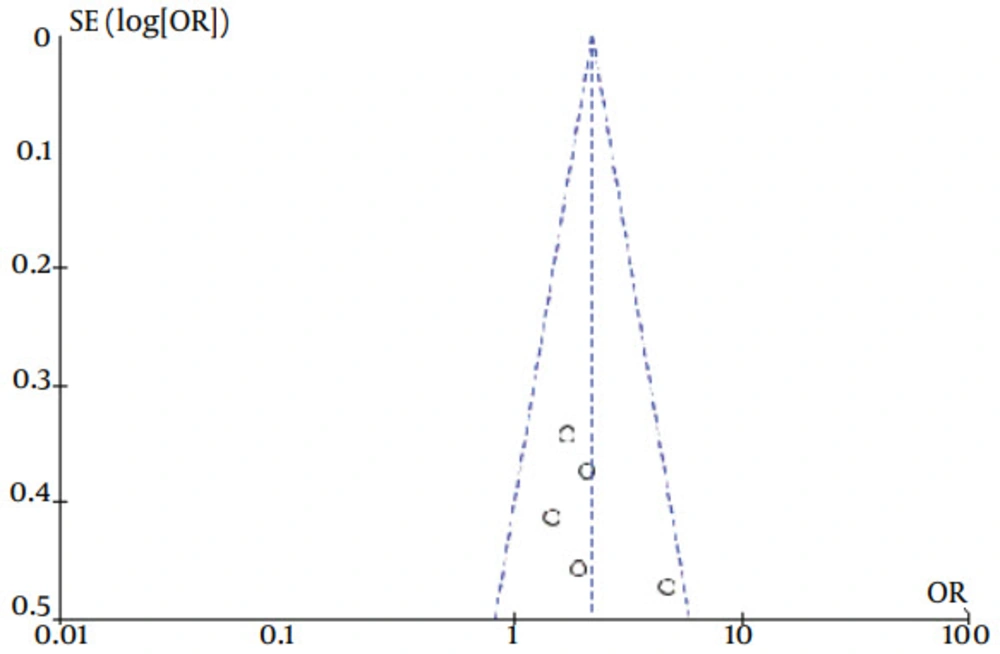

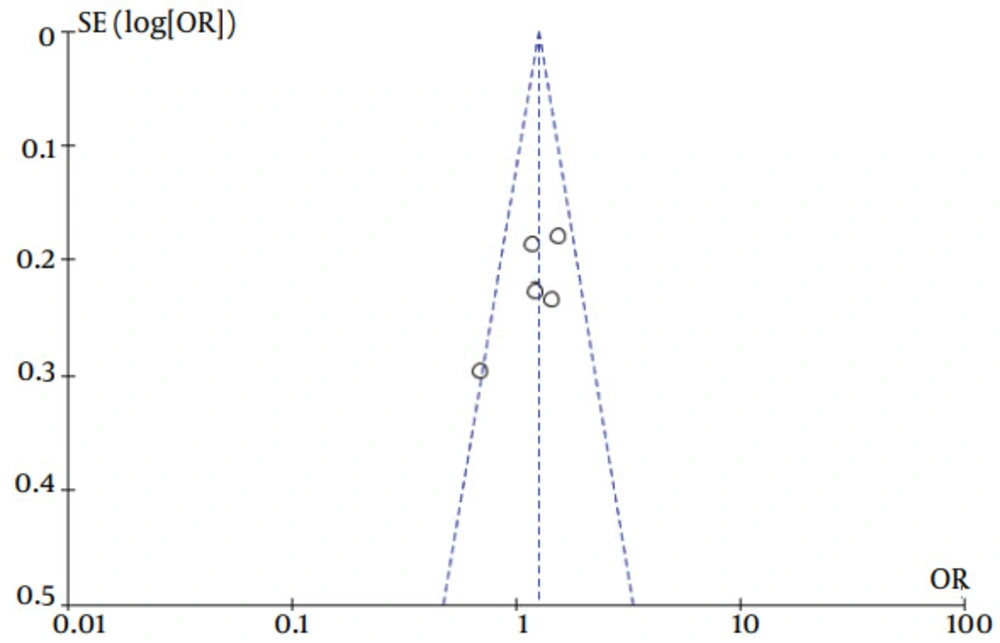

The current meta-analysis revealed that there was an association between gene polymorphisms of PNPLA3 and CHC. Gene polymorphisms of PNPLA3 were a risk factor for the presence of CHC. These analyses were based on data from studies irrespective of population ethnicity. Funnel plots to detect publication bias of studies on PNPLA3 tended towards an asymmetrical shape (Figures 4 and 5), suggesting that publication bias might have affected the findings of our meta-analysis.

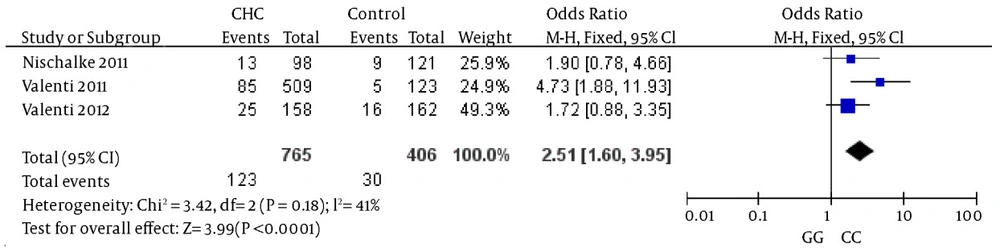

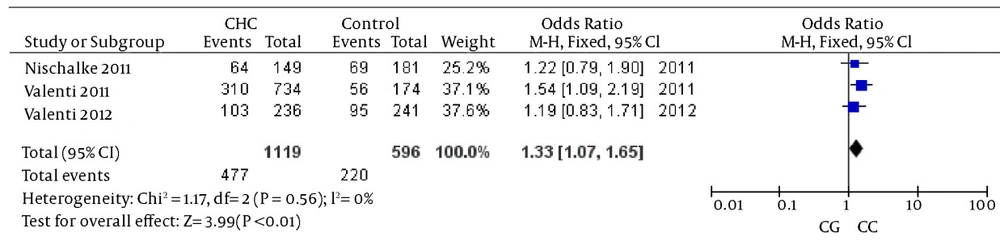

Specific ORs was not statistically significant (χ2 = 3.42, P = 0.18) when the GG genotype was compared with the CC genotype. The fixed-effect method was used to combine the results. The combined OR was 2.51 (95% CI: 1.60 - 3.95), which was statistically significant (P < 0.0001) (Figure 6). The same result was also found when the reference genotype CG was compared with the CC genotype (details in Figure 7). The heterogeneity test indicated that the variation of trial-specific ORs was not statistically significant (χ2 = 1.17, P = 0.56); the fixed-effect method was used to combine the results. The combined OR was 1.33 (95% CI: 1.07 - 1.65) and was statistically significant (P = 0.01). The subgroup analyses of ethnicity revealed a remarkable association between gene polymorphisms of PNPLA3 and CHC in Caucasians.

Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3, also called adiponutrin, encodes a 481-amino acid protein with a molecular mass of approximately 53 kDa that, in humans, is mainly expressed in intracellular membrane fractions in hepatocytes (21). Furthermore, PNPLA3 is induced in the liver after feeding and during insulin resistance by the master regulator of lipogenesis steroid regulatory element binding protein-1c (22). Wild-type (148I) PNPLA3 has lipolytic activity towards TG (21). The 148M mutation determines a critical amino acid substitution next to the catalytic domain, likely reducing access of substrates and the PNPLA3 enzymatic activity towards glycerolipids, thereby leading to the development of macrovesicular steatosis (23). The presence of steatosis has been associated with more aggressive histological features, faster progression of fibrosis, and poorer response to therapy. As for the mechanisms of lipolytic activity of PNPLA3, there is another study has reported on lipogenic function associated with the 148M variant, which would acquire the ability to synthesize phosphatidic acid from lysophosphatidic acid (24). The functional consequences of the I148M polymorphism is therefore still powerfully debated, and it may be hypothesized that PNPLA3 has additional physiological substrates. Human studies have also suggested a possible direct or indirect influence of PNPLA3 genotype on adipose.

In contrast to studies on both nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcoholic liver disease (ALD), liver damage (steatosis and fibrosis) related to PNPLA3 in CHC appears to primarily involve the homozygote G allele carriers, as reported by previous studies (10). Among the first to demonstrate the impact of the PNPLA polymorphism in patients with HCV infection were the studies of Valenti et al. (15) and Trepo et al. (25). They analyzed large cohorts of HCV patients in Europe and almost simultaneously reported the G allele of rs738409 SNP to be associated not only with the presence of histologically-determined liver steatosis, but also with the presence of cirrhosis and accelerated fibrosis progression. Corradini et al. further expanded these findings by reporting on an increased rate of hepatocellular carcinoma development in patients with the GG genotype of rs738409 in a cohort of 222 HCV patients (26). Indeed, by multivariate analysis, the GG genotype was found to be an independent factor associated with HCC development carrying a 2.23 OR. Taken together, these data rather unequivocally demonstrate a correlation between the G allele of the PNPLA3 SNP and a worse prognosis of CHC.

There are some points about the PNPLA3 SNP genotype that might explain its association with the progression of CHC. First, steatosis is known to negatively impact the natural history of HCV infection as it accelerates progression to cirrhosis (27). Second, liver steatosis has been shown to be a negative moderator of treatment outcome to interferon-based therapies. Patients with fatty liver had low sustained virological response rates across all HCV genotypes (28). Steatosis can promote inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress and has been shown to favor hepatocyte apoptosis in CHC (29). In addition to the effects on TG, the PNPLA3 genotype inhibits inflammation and fibrogenesis in the presence of severe liver fibrosis.

Adiponectin resistance may modify the interaction between genotype and environmental factors, which may increase the risk of developing CHC. An increased risk for addictive behavior, anemias requiring transfusions, percutaneous contact with infected blood, injection drug use, and tissue donations account for most HCV infections worldwide, which could influence the risk of having CHC. Whether the PNPLA3 genotype affects these factors is not known, and the exact mechanism behind this association remains poorly understood. Furthermore, PNPLA3 does not appear to have any direct association with HCV, as there is no known effect on viral load or treatment response. It is possible that this association is simply related to confounders, such as increased fibrosis from concomitant alcohol abuse or metabolic syndrome, among patients with the PNPLA3 GG genotype.

In subgroup analyses of ethnicity, the heterogeneity test indicated that the variation of trial-

The results of our meta-analysis showed that the G allele of the PNPLA3 rs738409 G > C SNP was associated with the presence of CHC. Individuals with the GG genotype had approximately a two-fold higher risk of having CHC when compared to individuals with the CC genotype. The GC heterozygous genotype was also associated with a smaller, but still significant risk. To our knowledge, this is the first published meta-analysis to comprehensively investigate the association between gene polymorphisms of PNPLA3 and CHC. In the current study, only publications in the English or Chinese language were analyzed. ‘Meta-analytical’ research, on 29 meta-analyses, investigating language bias has provided evidence that the OR estimated in meta-analyses from non-English publications were on average 0.8-fold (95% CI, 0.7 - 1.0) the OR estimates from English-written publications (30). For this reason, even if non-English publications had not been searched, this might have introduced only a small bias in the overall findings. Therefore, our language methodology is unlikely to have altered our main conclusions. However, the shape of the funnel plot seemed to be asymmetrical, suggesting that publication bias might have affected our findings.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, most studies to date were conducted on homogenous Caucasian populations from Europe or the United States. Studies among racially and ethnically diverse cohorts, including Hispanics, African Americans and other ethnicities are needed.

Second, because the information used in the current research was based on data from observational studies, the characteristics of each study population and the different methodologies of these studies should be taken into account when interpreting the results of our analysis. For example, different inclusion criteria for selection of the participants might have influenced the results of this research. In the current study, four studies only concerned adults (14, 15, 17, 18), four studies (14, 15, 17, 18) considered the proportion of females, while the remaining studies (16) did not take into account age or gender ratios.

Differences in age distribution and gender ratio could also be potential causes of variation in the results. Additionally, although we tried to maximize our efforts to identify all relevant published studies in peer-reviewed journals, it is possible that some escaped our attention.

Third, NAFLD and HBV infection were included as other control groups. Data on body mass index and diabetes were not included in this analysis due to a lack of association with the presence of CHC. Although false HCV positivity related to the PNPLA3 genotype was considered, there have been no reports of this association in the literature. Control group selection may affect the findings and interpretation of this research, and the use of different control groups could produce inconsistent results. The exclusion of NAFLD patients as controls in the current study precluded analysis of the contribution of steatosis independent of PNPLA3 status. Further meta-analysis on the NAFLD patient control subgroup with a larger sample size will be required in the future. It is assumed that a combined analysis based on studies with large samples can provide more accurate conclusions.

In conclusion, our analysis showed an association between gene polymorphisms of PNPLA3 and the presence of CHC; at least in Caucasians. This association had indications of possible publication bias, some heterogeneity, and less pronounced associations in prospective studies than in retrospective studies. Homogeneity of the methods for evaluating the degree of CHC, common gender, age and ethnicity would be critical to confirm the absence of association and, therefore, the lack of a causal role of gene polymorphisms of PNPLA3 in patients with CHC. Furthermore, the probable association of PNPLA3 polymorphism with the natural history of hepatitis C, such as spontaneous clearance of HCV acute infection, maybe another hypothesis for explanation of the difference in distribution of PNPLA3 genotypes in CHC and the control group. Given the importance of this issue, further prospective rigorous studies are required to confirm our results and to evaluate the potential of PNPLA3 to serve both as a predictor and a therapeutic target in CHC.