1. Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) constitutes the majority of primary liver cancers and is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). Although surgical resection and locoregional interventions are critical treatment modalities, liver transplantation (LT) is the only treatment option that increases survival in end-stage HCC patients (2). However, the majority of patients have already advanced disease at the time of diagnosis. In other words, only 30 - 40% of patients are diagnosed early enough for LT (2). Post-LT HCC recurrence is a major cause of death in recipients. While it is rare five years after transplantation, HCC recurrence within the first two years indicates a poor prognosis (3). Therefore, it is very important to determine optimal candidates for the transplantation procedure and to improve prognosis prediction ability.

Furthermore, due to the increasing number of patients waiting for LT and the shortage of organs, identifying the group that will benefit most from LT among HCC patients is critical. In cases where traditional selection criteria using morphological characteristics for HCC are extended, there is a decrease in survival after LT (4). In liver resection practice planned for the tumor, it is important to evaluate parameters such as portal hypertension involvement, tumor localization, and liver function (5). The Child-Pugh (CP) classification is used as a predictor of perioperative mortality in cirrhotic patients and as a tool for liver function evaluation. However, it has a number of weaknesses. Measurements such as ascites and encephalopathy are subjective. The covered parameters receive equal points and have patient-dependent measurement criteria. Albumin and ascites parameters also interact with each other (6).

As a separate predictive model, the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score has been used to predict survival in cases of decompensated liver function in patients on the transplantation list (7). According to the latest clinical trends, the necessity of more effective methods beyond the aforementioned models has been emphasized. The prognostic power of Albumin-Bilirubin Index (ALBI) is considered to be determined by albumin and bilirubin levels. As a result, the ALBI grade, a simple, easy-to-apply, and low-cost method for predicting survival and poor outcomes after liver resection, has recently been developed (8, 9).

Studies have reported that ALBI has prognostic significance in many cancers, such as gastric, colon, pancreatic, and cholangiocarcinomas, in addition to HCC, in its relationship with mortality (10). The precision strength of the ALBI grade detects even small changes in decompensated liver failure. This is especially important when there is a steady improvement in liver function, as in this case, the CP classification may not indicate liver dysfunction (11). From the LT perspective, some studies have mentioned that the ALBI grade showed a similar post-transplant complication rate as MELD. In addition, a strong correlation between ALBI grade and decreased survival has been reported (12, 13). However, the importance of the ALBI grade in terms of survival and prognosis after LT has not been evaluated in HCC patients to date.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate the ALBI grade as a predictor of long-term survival and tumor recurrence in patients after LT for HCC.

3. Methods

For this retrospective cohort study, patients with LT for primary HCC were recruited consecutively in two independent medical centers between 2012 and 2023. Both living donor LT and deceased donor LT procedures were performed in transplantation.

Inclusion criteria were patients who (A) were diagnosed with primary HCC based on pathology examination; (B) did not receive systemic treatment before LT due to HCC; (C) had complete medical records and follow-ups; (D) did not have biliary tract involvement or major vascular invasion; and (E) were HCC patients with cirrhosis.

Exclusion criteria were patients who: (A) had mixed type HCC based on pathological examination; (B) abandoned or disconnected follow-ups; (C) had non-HCC liver tumors based on pathological examination; (D) underwent retransplantation due to HCC recurrence; and (E) had post-LT perioperative mortality in the first 30 days.

Patients who had undergone pre-LT downstaging or bridging treatment were shown as locoregional treatment parameters. As a result, 200 patients were listed for analysis. All patients underwent three-month liver function tests and blood tests, including alfa feto protein (AFP), and six-month imaging [enhanced computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging enhanced with Gd-EOB-DTPA] within the first two years after LT.

Age, Body Mass Index (BMI), gender, pre-transplant liver disease, AFP, MELD score, CP, tumor number and largest tumor diameter, microvascular invasion (MVI), differentiation grade of the tumor, albumin, and bilirubin values were collected as patient data for the study. The ALBI score was calculated as (log10 bilirubin × 0.66) + (albumin × -0.085). Bilirubin was calculated as mg/dL, while albumin was calculated as g/L and grouped into three grades (grade 1: ≤ -2.60, grade 2: -2.60 to -1.39, and grade 3: ≥ -1.39) (14).

Survival was considered as the time interval from the date of LT for HCC to the death or last follow-up examination. All clinical variables for the patients were obtained from the results one week before LT. The overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were the primary outcomes of the study. The secondary outcomes were to analyze the recurrence rate and the clinical variables affecting it.

Since this is a retrospective study, written consent forms were not obtained from the patients. The study complied with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki standards as well as the current ethical guidelines. In addition, the study was approved by the institutional ethics board on January 9, 2025 (approval No.: ATADEK 2025-01/29).

Continuous variables are shown as mean or standard deviation. Categorical variables are shown as No. (%), and these variables are compared using Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test. Independent predictive factors for survival, as well as Kaplan-Meier analysis along with the log-rank test, were performed to determine OS and RFS. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to evaluate the OS and RFS rates. One-, three-, and five-year OS and RFS were used as objective variables for the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis.

To estimate independent prognostic factors, both univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. An alpha significance level of P < 0.05 was considered. SPSS 15.0 Windows software was used for statistical analysis. The relationship between ALBI grade and HCC prognosis was evaluated based on OS and RFS results, with hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

4. Results

The basic and clinicopathological characteristics of the study groups were generally similar. The mean age was 66.2 years for the patients, and the majority were male (83%). More than half of the causes of cirrhosis were due to HBV (56.5%), while the rest were cryptogenic (15%), HCV (13%), and others (14.5%). The ALBI grades of the patients were distributed as grade 1 (12.5%), grade 2 (51.5%), and grade 3 (36%; Table 1). The vast majority of patients were classified as CP A or B (93.5%).

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 166 (83.0) |

| Female | 34 (17.0) |

| Age | 66.2 (59.4 - 71.5) |

| BMI | 26 (24 - 29) |

| Diagnosis | |

| HBV | 113 (56.5) |

| Criptogenic | 30 (15.0) |

| HCV | 27 (13.5) |

| Ethanol | 13 (6.5) |

| Nash | 7 (3.5) |

| Autoimmune | 3 (1.5) |

| Budd-chiari | 3 (1.5) |

| Wilson | 2 (1.0) |

| Hemochromatosis | 1 (0.5) |

| Primer cholangitis | 1 (0.5) |

| ALBI | |

| Grade 1 | 25 (12.5) |

| Grade 2 | 103 (51.5) |

| Grade 3 | 72 (36) |

| CP | |

| A | 94 (47.0) |

| B | 93 (46.5) |

| C | 13 (6.5) |

| MELD | 11.5 (8 - 17) |

| AFP | 8.3 (3.52 - 48.5) |

| Tumor diameter (max.; mm) | 25 (16 - 40) |

| Number of HCC lesions | 2 (1 - 3) |

| Locoregional treatment | 65 (32.5) |

| Live | 154 (77.0) |

| Tumor recurrence rate | 32 (16.0) |

| Tumor differentiation grade | |

| Advanced | 35 (17.5) |

| Early | 66 (33.0) |

| Intermediate | 99 (49.5) |

| MVI | 75 (37.5) |

| Mortality | 46 (23.0) |

| Follow-up time (mo) | 56 (31 - 80) |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; Nash, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; ALBI, Albumin-Bilirubin Index; CP, Child-Pugh; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; AFP, alfa feto protein; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MVI, microvascular invasion.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or median (IQR).

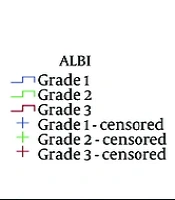

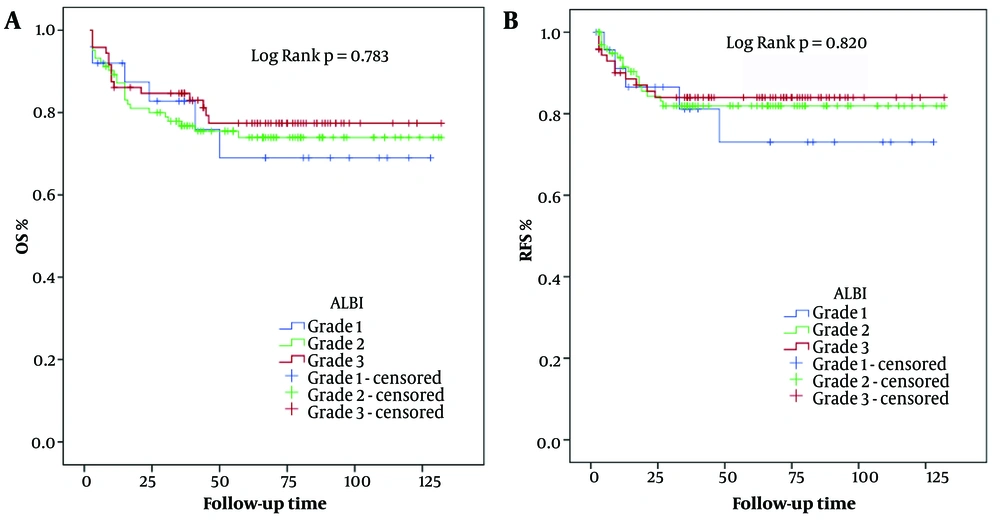

In terms of the distribution of ALBI grades, CP A and CP B were 60% and 40% in grade 1, CP A, CP B, and CP C were 54.3%, 41.7%, and 3.9% in grade 2, and CP A, CP B, and CP C were 32%, 55.5%, and 12.5% in grade 3, respectively. In the further subgroup analysis, the one-, three-, and five-year OS rates were 92.0%, 82.8%, and 69.0% in ALBI grade 1, 87.2%, 76.8%, and 73.9% in ALBI grade 2, and 86.1%, 84.7%, and 77.4% in ALBI grade 3, respectively (Figure 1A). Here, there was no significant difference in long-term OS between the groups. The one-, three-, and five-year RFS rates were 91.1%, 81.1%, and 73.0% in ALBI grade 1, 91.5%, 81.9%, and 81.9% in ALBI grade 2, and 90.0%, 84.0%, and 84.0% in ALBI grade 3 (Figure 1B). Likewise, long-term RFS outcomes were not significantly different between the groups.

In terms of recurrence risk effects, MVI, tumor number, and maximum tumor size were found to be significant factors in both univariate and multivariate analyses (Table 2). Regarding mortality risk effects, MVI, tumor count, and maximum tumor size were significant factors in univariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, however, tumor number and maximum tumor size remained significant factors (Table 3). The MVI, tumor number, and size turned out to be independent prognostic factors for recurrence, while tumor number and size were independent factors for predicting OS.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-Value | HR | 95% CI | P-Value | HR | 95% CI | |

| AFP | 0.759 | 1.000 | 0.999 - 1.001 | 0.906 | 1.000 | 0.999 - 1.001 |

| MELD | 0.503 | 0.981 | 0.928 - 1.037 | 0.737 | 0.986 | 0.908 - 1.071 |

| Child Pugh (Ref: A) | 0.526 | 0.864 | ||||

| B | 0.379 | 0.718 | 0.343 - 1.503 | 0.984 | 1.010 | 0.409 - 2.492 |

| C | 0.634 | 1.347 | 0.395 - 4.599 | 0.626 | 1.485 | 0.303 - 7.273 |

| Tumor differentiation grade (Ref: Early) | 0.295 | 0.409 | ||||

| Advanced | 0.139 | 2.051 | 0.791 - 5.318 | 0.204 | 0.473 | 0.149 - 1.503 |

| Intermediate | 0.644 | 1.224 | 0.519 - 2.887 | 0.252 | 0.565 | 0.212 - 1.501 |

| MVI | < 0.001 | 7.926 | 3.261 - 19.262 | < 0.001 | 6.039 | 2.092 - 17.433 |

| Number of HCC lesions | < 0.001 | 1.188 | 1.112 - 1.269 | < 0.001 | 1.179 | 1.089 - 1.277 |

| Tumor diameter (mm) | < 0.001 | 1.028 | 1.015 - 1.040 | 0.006 | 1.021 | 1.006 - 1.037 |

| ALBI (Ref: Grade 1) | 0.822 | 0.476 | ||||

| Grade 2 | 0.612 | 0.771 | 0.283 - 2.106 | 0.228 | 0.518 | 0.178 - 1.510 |

| Grade 3 | 0.535 | 0.716 | 0.249 - 2.061 | 0.500 | 0.666 | 0.205 - 2.165 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; AFP, alfa feto protein; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; MVI, microvascular invasion; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ALIBI, Albumin-Bilirubin Index.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-Value | HR | 95% CI | P-Value | HR | 95% CI | |

| AFP | 0.774 | 1.000 | 0.999 - 1.001 | 0.412 | 0.999 | 0.998 - 1.001 |

| MELD | 0.932 | 0.998 | 0.953 - 1.045 | 0.607 | 0.985 | 0.931 - 1.043 |

| Child Pugh (Ref: A) | 0.353 | 0.195 | ||||

| B | 0.503 | 1.234 | 0.667 - 2.281 | 0.243 | 1.518 | 0.753 - 3.062 |

| C | 0.153 | 2.052 | 0.766 - 5.499 | 0.077 | 2.909 | 0.891 - 9.505 |

| Tumor differentiation grade (Ref: Early) | 0.436 | 0.972 | ||||

| Advanced | 0.198 | 1.711 | 0.755 - 3.881 | 0.935 | 0.961 | 0.370 - 2.496 |

| Intermediate | 0.505 | 1.268 | 0.631 - 2.549 | 0.899 | 1.051 | 0.487 - 2.267 |

| MVI | 0.023 | 1.962 | 1.098 - 3.504 | 0.384 | 1.373 | 0.673 - 2.805 |

| Number of HCC lesions | 0.002 | 1.117 | 1.041 - 1.199 | 0.011 | 1.108 | 1.024 - 1.198 |

| Tumor diameter (mm) | 0.002 | 1.016 | 1.006 - 1.027 | 0.028 | 1.013 | 1.001 - 1.026 |

| ALBI (Ref: Grade 1) | 0.786 | 0.649 | ||||

| Grade 2 | 0.909 | 0.949 | 0.389 - 2.315 | 0.890 | 0.938 | 0.378 - 2.330 |

| Grade 3 | 0.595 | 0.773 | 0.300 - 1.994 | 0.465 | 0.687 | 0.252 - 1.877 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; AFP, alfa feto protein; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; MVI, microvascular invasion; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ALIBI, Albumin-Bilirubin Index.

5. Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the prognostic value of preoperative ALBI grade in predicting OS and RFS in patients with HCC who underwent LT. We divided the ALBI grade into three grades in our cohort and aimed to compare them. Our results showed that ALBI grade was not a long-term prognostic factor. Further subgroup analysis revealed that even in advanced grades, long-term survival rates were similar to those of LT for other reasons.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate the association of ALBI grade with long-term survival and recurrence outcomes in HCC patients undergoing LT. One study evaluated the importance of ALBI in LT. Our study confirmed that ALBI grade does not stratify the prognosis in patients with LT for HCC. Therefore, we showed that ALBI cannot be used as a criterion to identify HCC patients who may benefit more from LT.

Recently, there has been an increasing number of studies indicating that the ALBI score could improve the assessment of liver function against different treatment modalities, including immunotherapy, non-curative locoregional therapy, and systemic therapies in early-stage HCC patients (15-18). However, apart from the characteristics of the tumor itself in improving OS in this group of patients, increasing attention is paid to improving liver function assessment, which is central to the prognostic role. In the absence of LT in a short period of time, the most effective treatment for HCC is curative resection. However, HCC recurrence often develops in 80% of patients on the background of residual cirrhotic or fibrotic liver disease (10).

Mainly, the potential effectiveness of the ALBI score in eliminating subjective variables in predefined grading systems such as CP is known. Its benefit has been confirmed in primary biliary cirrhosis and acute-chronic liver failure due to any cause. This retrospective study involving LDLT showed that it was equal to the MELD score in predicting perioperative mortality and postoperative morbidity. However, this report did not cover long-term outcomes (13). Furthermore, a retrospective study involving DDLT patients showed an association between ALBI grade 3 and a low survival rate (12). However, this study did not cover LDLT recipients, either. They all included patients who had undergone LT for any reason.

Another study comparing MELD and ALBI in terms of survival predictive value showed that the prognostic effect of hematological factors on survival was limited and that a combination of multiple factors was necessary (19). In fact, the ALBI score also reflects the patient’s overall nutritional status. Therefore, unlike MELD, the ALBI score was found to be correlated with long-term mortality. Infection, exacerbated by low immunity and profound malnutrition, can adversely affect survival. Although this suggests the possibility of developing cancer and increasing the risk of recurrence, nutritional insufficiency will improve over time, as it disappears in the cirrhotic liver in patients with LT, unlike cirrhotic HCC patients who undergo resection.

Indeed, there is no prospective, large-scale study demonstrating the effect of nutritional and immunodeficiency status on post-LT HCC recurrence. We did not specifically evaluate the predictive survival ability of ALBI in the detection of non-tumor fatal complications in LT patients. The ALBI grade was shown to predict survival in non-malignant liver disease more effectively than the MELD score and CP. However, it was also shown to have prognostic value in non-hepatic malignant tumors as well as certain non-hepatic diseases such as acute or chronic heart failure, aortic dissection, and acute pancreatitis (10). This observation may cast doubt on the specificity of ALBI in terms of assessing liver function. The ALBI grade is strongly associated with hepatic fibrosis, which is a strong risk factor for HCC development in cases with continuing viral response (20).

Similarly, it was shown that ALBI grade predicts RFS, OS, and prognosis more accurately after curative resection in HCC patients (21, 22). However, our study showed that tumor differentiation grade significantly predicted non-responsiveness to locoregional treatment based on radiological or clinical evaluation, MVI, maximum tumor size, tumor number, and adverse HCC prognosis, and was an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis. This was in line with recent studies (23, 24).

There is no requirement to assess hepatic function reserve and estimate the risk of post-LT liver failure in LT for HCC. Recently, several studies evaluated ALBI grade and current HCC treatment algorithms. One study found that the prognostic performance of CP-based BCLC and ALBI grade was similar, while another study emphasized that the prognostic feature of ALBI grade can be employed to overcome heterogeneity in survival in BCLC cases (25, 26). Different scoring systems combined with ALBI were proposed to predict the HCC prognosis and compare treatment outcomes at different centers (21, 27, 28). Their results showed that ALBI grade was more effective in determining HCC prognosis when used in conjunction with total staging scoring systems.

Another study proposed a nomogram based on the combination of ALBI grade and other clinical outcomes for two- and five-year survival estimation in HCC recurrence after hepatectomy (29). However, they analyzed survival after the recurrence developed. Another study that divided two different prognostic subgroups into two groups also proposed a modified ALBI score, m-ALBI (1, 2a, 2b, 3). This was later reported to be a better prognostic predictive method after curative treatment for early-stage HCC together with tumor node metastasis (TNM). However, even between these two subgroups, there was a significant mismatch in median survival (90 months in 2a versus 62 months in 2b) (30).

The prognosis of HCC patients is related to factors concerning both the functional capacity of the liver and the tumor itself. Liver dysfunction not only affects surgical safety but also impairs long-term survival and postoperative recurrence (31). The ALBI grade is considered a robust and useful approach to assess liver function in cirrhotic patients who may have HCC, but its prognostic predictive power is weakened in cases of decompensated cirrhosis. The HCC does not distinguish the ALBI grade in non-cirrhosis patients. Similarly, it does not include prognostic factors related to the characteristics of the tumor itself. Eighty percent of HCC develops on the background of cirrhosis. Our formal statistical analysis showed that since this predisposing factor was eliminated by LT, there was no change in HCC-related OS and RFS outcomes among ALBI grades.

Though single-centered, previous studies showed mounting evidence of poor prognosis in HCC patients with high-ALBI grade liver resection. A recent meta-analysis indicated that it was an independent predictor of OS in patients undergoing curative resection. However, this included retrospective studies that could cause selection bias. Additionally, there was a lack of publications with negative results in data analysis. Moreover, the number of patients with ALBI grade 3, which showed a worse prognosis in long-term outcomes, was very small (14). In another similar study, ALBI grade 3 was also ignored. In fact, there were more cases of HCC with BCLC-C and extra disease in ALBI grade 2 than in grade 3 (32).

Nevertheless, it is still debated whether the ALBI grade can be used in recurrence estimation. Our analysis showed that the ALBI grade was not associated with recurrence, which aligns with recent studies (22, 33). Similarly, it was reported that the ALBI grade was not prognostic for OS, RFS, and tumor recurrence after ablative treatment in transplantable HCC patients. However, the study did not include ALBI grade 3 patients, while ALBI grade 2 patients constituted 15% (34). In contrast, in our analysis, the majority of cases were ALBI grade 2 and 3.

When the ALBI grade is used at the same cut-off value, both the prognosis of the tumor in patients with different tumor burdens and the risk of liver failure that may develop after hepatectomy in cirrhotic patients cannot be evaluated reliably. To increase the probability of predicting the risk of liver failure, it may be more effective to evaluate the ALBI grade at the most appropriate time point of the disease period, as well as the combination of different quantitative or dynamic tests and scoring systems.

The ALBI grade has certain limitations in evaluating the prognosis in HCC patients undergoing LT. Additionally, one of the prognostic limitations of the ALBI grade in HCC patients undergoing resection is the disregard of portal hypertension, which is associated with both reduced survival and an increased risk of postoperative complications in these patients, as this is also associated with the risk of recurrences (35).

When recurrence is diagnosed, patients may receive treatments such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), hepatic resection, systemic therapy, or re-transplantation therapy. The treatment of recurrence depends on factors such as the age of the patient, the number and size of the tumor, the involvement of tumors outside the liver, including lymph nodes, and the availability of a suitable donor. Therefore, regular follow-up of patients and early diagnosis of recurrence status improve subsequent recurrence treatment and outcomes.

Our study has some limitations. Due to its retrospective nature, it was difficult to avoid selection bias. Although it was a two-centered study, the total number of patients was relatively small.

5.1. Conclusions

Pre-transplant ALBI grade did not independently predict long-term survival or recurrence following LT for HCC. It is important to clarify some aspects of liver dysfunction in the relationship between ALBI and mortality or whether ALBI has prognostic power in HCC independently of liver function. Although it is argued that the regulatory effects of albumin and bilirubin on both malnutrition and the immune system are related to this issue, the underlying prognostic mechanism of ALBI is still not elucidated. However, for the ALBI grade to be used reliably in the prediction of pre-LT prognosis in HCC patients, prospective, large-volume studies combined with risk factors that reflect the inherent characteristics of the tumor are needed.