1. Introduction

An abscess is a localized collection of infected fluid. A perianal abscess is an acute suppurative infection that develops in the soft tissues surrounding the anal canal and rectum, forming a contained abscess (1). This represents one of the most common clinical conditions encountered in anorectal surgery. While specific anatomical classifications exist for different types of perianal abscesses, the initial management approach remains consistent in most cases, hence the general use of the term "perianal abscess" (2). Approximately 90% of primary perianal abscesses result from infection of the anal crypt glands (3). Secondary cases may develop due to trauma, Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, or malignancies. The condition shows a predilection for adults aged 20 to 60 years and occurs more frequently in males than females (4). The hallmark clinical features include persistent pain and swelling in the perianal region. Depending on the location and severity of inflammation, systemic manifestations such as fever, chills, and fatigue may also occur (5). The standard treatment involves incision and drainage (I&D) of the abscess. Liver abscess following perianal abscess drainage represents an uncommon but potentially serious complication (1, 5). This case report describes such an occurrence in a previously healthy adult, highlighting the importance of recognizing this rare sequela.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Ethical Approval and Patient Baseline

We adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Anorectal Hospital (Approval No.: 2025ELLHA-025-01), with written informed consent was obtained. A 33-year-old immunocompetent male (non-smoker, no comorbidities) presented with a 2-day history of perianal swelling and pain. Physical examination revealed perianal edema at the 11 to 1 o’clock positions with erythema but no ulceration. Laboratory tests showed marked leukocytosis [white blood cell count (WBC) 25.08 × 109/L], elevated neutrophils, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Transrectal ultrasound confirmed a perianal abscess.

2.2. Surgical Intervention (Postoperative Day 0)

Under local anesthesia (1% lidocaine), a 1.5 to 2.0 cm radial incision was made at the point of maximal fluctuance, carefully avoiding hemorrhoidal tissue. Purulent material was completely evacuated, and the abscess cavity was irrigated thoroughly with warm normal saline until clear effluent was achieved. A latex drain was inserted to maintain patency, and the wound was packed with sterile gauze. Standard perioperative antiseptic measures, including povidone-iodine skin preparation and aseptic technique, were strictly followed. The procedure was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged 2 hours postoperatively with prescriptions for etimicin sulfate (analgesic) and lornoxicam (anti-inflammatory).

2.3. Early Postoperative Course (Postoperative Day 1 - 3)

The patient reported mild discomfort at the surgical site but no systemic symptoms during the first two postoperative days. On postoperative day (POD) 3, during a scheduled dressing change, he developed a low-grade fever (< 38°C). The surgical site appeared well-healed without erythema, swelling, or purulent discharge, suggesting no local infection recurrence. Vital signs were otherwise stable, and no additional interventions were undertaken at this time.

2.4. Systemic Infection Emergence (Postoperative Day 4)

By POD 4, the patient’s condition deteriorated abruptly, with the onset of high-grade fever (40.4°C) and chills. He presented to an external emergency department, where physical examination revealed no worsening of the perianal wound but raised concerns for systemic infection. Blood cultures were drawn prior to antibiotic administration, and empirical intravenous ampicillin-sulbactam (3 gram every 6 hours) was initiated to cover potential gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic pathogens. The patient was admitted for monitoring and continued IV therapy.

2.5. Diagnosis of Pyogenic Liver Abscess (Postoperative Day 6)

Despite 48 hours of antibiotic therapy, the patient reported persistent fever and new-onset right upper quadrant (RUQ) tenderness. He returned to our institution for further evaluation. Abdominal examination revealed RUQ tenderness without rebound or Murphy’s sign. Laboratory tests showed normalized leukocyte count but elevated liver enzymes (AST 107.2 U/L, ALT 210.9 U/L), suggesting hepatic involvement. Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT and ultrasonography demonstrated multiple hypodense lesions in the liver parenchyma (Figures 1 and 2), the largest measuring 3.5 cm with attenuation values of 15 - 30 Hounsfield units (HU). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of pyogenic liver abscesses, likely secondary to hematogenous spread from the perianal abscess. The patient was transferred to the infectious diseases unit for targeted management.

A contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan showed multiple round, slightly low-density lesions (arrows) of varying sizes within the liver parenchyma, with clear margins and heterogeneous internal density. The largest lesion measured approximately 35 mm in diameter, with attenuation values of 15 to 30 HU, compared to normal liver parenchyma measuring approximately 50 to 70 HU.

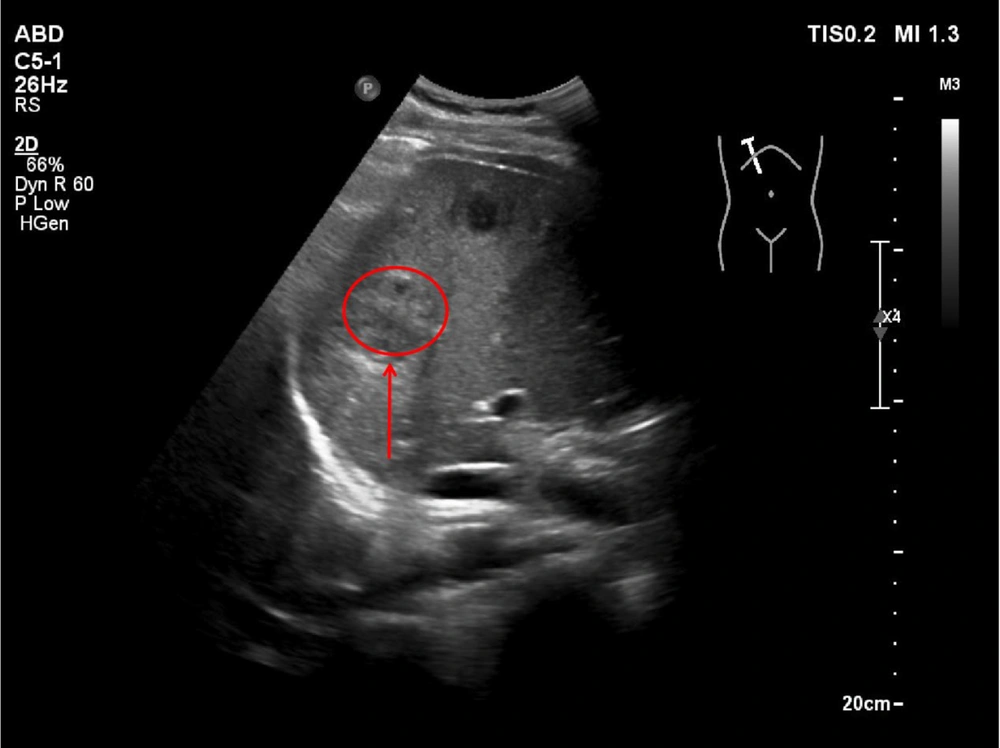

2.6. Abdominal Ultrasound Findings

The abdominal ultrasound of the liver revealed multiple hypoechoic lesions (arrows) with irregular margins and heterogeneous echotexture. Color Doppler imaging demonstrated peripheral vascular signals (arrow), consistent with pyogenic liver abscesses. The largest lesion measured approximately 3.5 cm in diameter. The surrounding liver parenchyma exhibited reactive hyperechogenicity.

2.7. Microbiological Findings and Pathogenesis (Postoperative Day 4 - 6)

Blood cultures obtained on POD 4 turned positive after 18 hours of incubation in the automated BACTEC system, with Gram staining showing gram-positive cocci in both clusters and chains. MALDI-TOF MS final identification confirmed the presence of Staphylococcus epidermidis in both aerobic bottles and Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus) in one aerobic bottle. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing via broth microdilution following CLSI M100 guidelines revealed that S. epidermidis was susceptible to oxacillin (MIC ≤ 0.25 μg/mL), ampicillin-sulbactam (MIC ≤ 4.2 μg/mL), and levofloxacin (MIC ≤ 0.5 μg/mL), while S. pyogenes showed susceptibility to penicillin (MIC ≤ 0.03 μg/mL), ampicillin (MIC ≤ 0.06 μg/mL), and levofloxacin (MIC ≤ 1 μg/mL).

A notable diagnostic limitation was the absence of anaerobic cultures or liver abscess aspirates, which resulted from the small size and multifocal nature of the lesions combined with the rapid clinical response to empiric therapy; this is significant as Bacteroides fragilis (resistant to levofloxacin) is commonly associated with perianal abscesses. The pathogenesis is thought to involve procedural bacteremia during I&D, where organisms entered the portal circulation through the hemorrhoidal venous plexus, followed by seeding of hepatic sinusoids due to their fenestrated endothelium and phagocytic Kupffer cell activity. Subsequent abscess formation was facilitated by bacterial virulence factors, including biofilm production by S. epidermidis and M protein from S. pyogenes, alongside potential transient pylephlebitis (portal vein inflammation) that resolved before imaging could detect it.

2.8. Therapeutic Strategy and Rationale (Postoperative Day 6 - 9)

The antimicrobial regimen was carefully tailored considering multiple factors, with empiric coverage maintained through ampicillin-sulbactam administered at 3 g IV every 6 hours, which provided optimal β-lactamase stability against S. epidermidis, anaerobic coverage for possible Bacteroides, and favorable biliary penetration reaching 40% to 60% of serum levels. Adjunctive therapy with polyene phosphatidylcholine at 456 mg PO three times daily was added due to elevated transaminases (AST/ALT > 5 × ULN), the need for prolonged antibiotic use, and its demonstrated hepatoprotective effects in drug-induced liver injury. A five-day course of IV therapy was implemented to ensure adequate tissue levels in multilocular abscesses, achieve clinical stability (with the patient remaining afebrile for over 48 hours), and complete the 7-day sepsis protocol.

2.9. Transition to Oral Therapy and Monitoring (Postoperative Day 9 - 35)

The step-down to oral levofloxacin at 500 mg daily was justified by the documented susceptibility of both isolates, favorable pharmacokinetics featuring a hepatic tissue:serum ratio of 8:1, and excellent bioavailability (99%) that enabled outpatient management. This transition was further supported by patient-specific factors, including clinical improvement marked by absence of fever and resolving RUQ pain, abscess characteristics (all < 4 cm with no drainage required), and reliable follow-up capability. The monitoring protocol included weekly clinical reviews to assess fever, abdominal pain, and wound status, biweekly laboratory tests for liver function tests (LFTs), CRP, and complete blood count (CBC), as well as compliance verification through pill counts.

2.10. Radiological and Clinical Resolution (Week 5 Follow-up)

Follow-up triple-phase liver CT at week 5 showed complete resolution of all hepatic lesions, normal portal venous flow on Doppler, and no evidence of chronic changes such as fibrosis or calcifications. Clinically, the patient achieved normalization of liver enzymes (AST 22 U/L, ALT 26 U/L), undetectable CRP (< 3 mg/L), and a full return to work without any limitations.

3. Discussion

3.1. Perianal Abscess and Pathogen Involvement

A perianal abscess is characterized by an acute purulent infection in the soft tissues or spaces surrounding the anal canal and rectum, culminating in abscess formation (6). The principal pathogens involved include Escherichia coli, S. aureus, Streptococcus species, and anaerobes such as Bacteroides and Peptostreptococcus (7). Incision and drainage, a standard treatment for perianal abscess, aims to evacuate pus and relieve pressure. However, as this case vividly illustrates, it can be complicated by the development of pyogenic liver abscess, a rare yet severe consequence.

3.2. Prognostic Considerations: Age and Immunocompetence

Historically, pyogenic liver abscess was associated with mortality rates in the range of 10% to 20% (8). However, with the advent of modern imaging modalities like high-resolution CT scans and advanced ultrasound techniques, timely abscess drainage procedures, and the availability of targeted antimicrobial agents, contemporary cohorts show significantly improved outcomes. A recent population-based study reported a 30-day mortality of 7.4% (8). Independent risk factors identified in this study included polymicrobial bacteremia, the absence of abscess drainage, underlying congestive heart failure, pre-existing liver disease, and elevated admission bilirubin levels. These comorbid conditions are typically less prevalent in otherwise healthy young adults.

Earlier research suggested that age was a crucial determinant of mortality in pyogenic liver abscess cases (9, 10). However, more recent comparative analyses, which have incorporated aggressive management strategies including early intervention and optimized antimicrobial therapy, indicate that older patients can achieve outcomes comparable to their younger counterparts. Nevertheless, the elderly often present with a higher burden of comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and chronic lung diseases, which can complicate the clinical course and lead to longer hospitalizations. In this case, our patient, being young and immunocompetent, with small-sized liver lesions that were promptly recognized and managed, was situated at the lower-risk end of the prognostic spectrum. This aligns with contemporary series and case reports documenting favorable outcomes in healthy young adults with pyogenic liver abscess (11, 12), in contrast to the higher mortality figures reported in older literature and in populations with multiple comorbidities (13).

3.3. Pathophysiological Mechanisms: Bacteremia and Portal Venous Seeding

The relationship between I&D procedures and bacteremia remains complex. A prospective study involving afebrile adults who underwent I&D for localized cutaneous abscesses failed to detect any transient bacteremia, suggesting that systemic (arterial) seeding as a direct consequence of uncomplicated I&D is infrequent (14). However, anorectal procedures are distinct in this regard. Due to the rich vascular supply and the presence of a mucosal barrier in the anorectal region, these procedures have been associated with transient bacteremia, as well as rare occurrences of septic emboli and liver abscesses (15). Mucosal disruption during anorectal I&D can potentially provide a portal of entry for microorganisms into the circulation. Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal system, commonly known as pylephlebitis, is a well-recognized mechanism underlying the development of multiple hepatic abscesses following intra-abdominal infections (16). The portal venous system, which drains blood from the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and spleen to the liver, can serve as a conduit for bacteria to reach the liver. A recent systematic review comprehensively summarized the etiologies, characteristic imaging hallmarks, and outcomes associated with pylephlebitis (16). Case reports in the literature further support the existence of an anorectal-to-portal-liver pathway, with instances of pylephlebitis and pyogenic liver abscess described following anorectal interventions such as hemorrhoidal banding (16). In our patient, the temporal relationship between perianal abscess I&D and the subsequent development of liver abscesses, the absence of any evident biliary pathology, and the presence of multifocal small hepatic lesions strongly suggest the plausibility of portal venous seeding. However, due to the lack of portal venous imaging, which could have detected pylephlebitis, and the absence of liver aspirate cultures, the exact route of infection cannot be definitively established. Future cases could benefit from the inclusion of Doppler ultrasound or contrast-enhanced CT evaluation of the portal venous system, as well as, when technically feasible, the culturing of hepatic lesions to strengthen the causal inference (16).

3.4. Pathogen Specificity: Atypical Organisms in Context

In many Asian countries, particularly in regions such as Taiwan, Singapore, and parts of China, Klebsiella pneumoniae has emerged as the predominant pathogen in community-acquired pyogenic liver abscess (13). The hypermucoviscous K1/K2 capsular types of K. pneumoniae are of particular concern due to their enhanced ability to cause metastatic spread. In our patient, K. pneumoniae was not isolated from the blood cultures. Moreover, liver aspirate cultures were not performed, primarily because of the small and multifocal nature of the lesions, along with the rapid response to empiric therapy. Additionally, the patient did not exhibit common risk factors associated with K. pneumoniae infection, such as diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, or recent travel to hyperendemic regions.

Instead, the blood cultures obtained on POD 4, prior to the initiation of antibiotic therapy, grew S. epidermidis (in both aerobic bottles) and S. pyogenes (group A Streptococcus, in one aerobic bottle). The fact that these organisms were recovered from multiple culture sets and separate venipuncture sites strongly supports their role as the true causative pathogens. Both S. epidermidis and S. pyogenes are atypical pathogens in the context of pyogenic liver abscess, which more commonly involves enteric Gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes. Staphylococcus epidermidis, a coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and a common inhabitant of the skin microbiota, is often dismissed as a contaminant in culture results. However, in this case, its growth across multiple culture sets, in conjunction with persistent fever and compatible imaging findings, strongly indicates true bacteremia. The recent perianal surgical wound likely provided a portal of entry for this skin flora, facilitating its access to the portal venous system and subsequent hepatic seeding. Streptococcus pyogenes, best known for its association with upper respiratory tract infections such as pharyngitis, is also capable of causing invasive diseases, including bacteremia and deep-seated abscesses. Although no recent pharyngeal infection was documented in our patient, the possibility of transient bacteremia originating from an unrecognized oropharyngeal source cannot be excluded. The concurrent isolation of these two organisms raises the intriguing possibility of polymicrobial seeding, potentially facilitated by mucosal disruption during the I&D procedure. The pathogenic role of these organisms in this case is further supported by the temporal association with the surgical intervention and the favorable response to targeted antibiotic therapy, despite the absence of liver aspirate cultures.

3.5. Clinical Implications and Management Considerations

The systemic dissemination of bacteria during perianal abscess I&D can occur due to several factors. Improper surgical technique, such as inadequate aseptic precautions during the procedure, can introduce bacteria into the bloodstream or lymphatic system. Ineffective postoperative drainage, resulting from factors like the incorrect placement of drainage tubes or insufficient management of the drainage system, can lead to the accumulation of residual pus. This residual pus provides an ideal environment for bacterial growth and proliferation, increasing the risk of bacterial spread via the hematogenous or lymphatic routes. The liver, with its dual blood supply from the hepatic artery and the portal vein, is particularly vulnerable to bacterial colonization and abscess formation. The portal venous system, which drains the anorectal region, can carry bacteria from the perianal abscess to the liver. Additionally, the rich vascularity of the liver and the presence of Kupffer cells, which are part of the mononuclear phagocyte system, can either facilitate the clearance of bacteria or, under certain circumstances, contribute to the formation of abscesses if the immune response is overwhelmed. In our patient, the postoperative imaging findings, such as the presence of multiple small hepatic lesions, strongly suggest hematogenous spread of bacteria.

This case underscores the critical importance of promptly investigating persistent postoperative fever in patients who have undergone perianal abscess I&D. The differential diagnosis should not be limited to local complications but should also include the possibility of systemic infections such as pyogenic liver abscess. Diagnostic modalities such as sonography and CT are invaluable for visualizing hepatic lesions, accurately assessing their size, location, and number, and guiding drainage procedures when necessary. The management of pyogenic liver abscess typically begins with the initiation of empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics. The choice of antibiotics should be guided by the likely pathogens based on the patient’s clinical presentation, risk factors, and local epidemiology. Once the results of culture and sensitivity testing are available, the antibiotic regimen can be tailored to target the specific pathogens identified. While there is currently no consensus regarding the optimal size threshold for abscess drainage, in general, most small abscesses respond well to prolonged antibiotic therapy alone. Larger abscesses, on the other hand, often require percutaneous drainage under imaging guidance to facilitate the evacuation of pus and promote resolution. Surgical intervention is reserved for cases that are refractory to antibiotic treatment or those complicated by abscess rupture, which can lead to life-threatening conditions such as peritonitis (17).

3.6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this case presents a rare but severe complication of perianal abscess I&D, highlighting the importance of a high index of suspicion for liver abscess in patients with persistent fever following perianal abscess procedures. Early recognition, prompt imaging diagnosis, and the implementation of tailored antimicrobial therapy are crucial for achieving successful outcomes. Clinicians should be vigilant in monitoring for systemic infections in these patients to prevent treatment delays and the development of potentially life-threatening complications.