1. Context

Echinococcosis, also known as hydatid disease, is a zoonotic parasitic infection caused by the larval stages of Echinococcus granulosus [cystic echinococcosis (CE)] and E. multilocularis [alveolar echinococcosis (AE)]. These pathogens severely threaten human health and the livestock industry (1). While CE cysts grow endophytically within a protective fibrous capsule, allowing potential surgical enucleation, hepatic alveolar echinococcosis (HAE) exhibits exogenous infiltrative growth without clear tissue boundaries. Primarily affecting the liver, HAE progressively destroys the hepatic parenchyma through mechanical compression, enzymatic degradation, and toxin secretion, ultimately inducing fibrosis and liver failure. Metastasis via the hepatic veins to the lungs or brain underscores its malignancy, earning the epithet "parasitic cancer" due to its dismal prognosis.

The gut and liver, as central hubs of metabolic and immune regulation, engage in intricate bidirectional crosstalk through the "gut-liver axis", a network integrating portal circulation, biliary systems, and circulatory mediators. This axis orchestrates nutrient processing, xenobiotic detoxification, and immune surveillance while dynamically interacting with gut microbiota-derived metabolites [e.g., bile acids and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)]. Emerging microbiome research has revealed that hepatic bile acid synthesis and immune modulation reciprocally shape gut microbial ecology. Disruption of this equilibrium triggers a pathogenic triad: Intestinal barrier dysfunction, dysbiosis, and bile acid dysmetabolism, driving the development of hepatic steatosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Among hepatopathies, HAE is characterized by aggressive progression and limited therapeutic options. Recent studies have highlighted compelling links between gut microbiota perturbations and HAE pathogenesis. Multi-omics approaches are now mapping the "parasite-microbiota-host" interactome, aiming to identify microbial biomarkers for early diagnosis and develop microbiota-directed therapies.

1.1. Determinants of Gut Microbiota Composition

The gut microbiota exists in a dynamic equilibrium and exhibits remarkable interindividual heterogeneity in composition and structure. While its core functional attributes remain relatively stable, microbial diversity is shaped by a multitude of determinants, including geographical variations and host-specific intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Current evidence highlights three principal dimensions of investigation: (1) Endogenous factors (e.g., host genetics, circadian rhythms, and immune status), (2) exogenous modulators (e.g., dietary patterns, antibiotic exposure, and environmental toxins), and (3) dysbiosis-associated pathologies (e.g., metabolic disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, and neuropsychiatric conditions). Emerging intervention strategies, including precision nutrition, lifestyle optimization, and microbe-based therapeutics, have shown significant potential for targeted microbiota modulation and ecological network restoration.

1.1.1. Gut-Liver Axis Regulation of Intestinal Microbiota

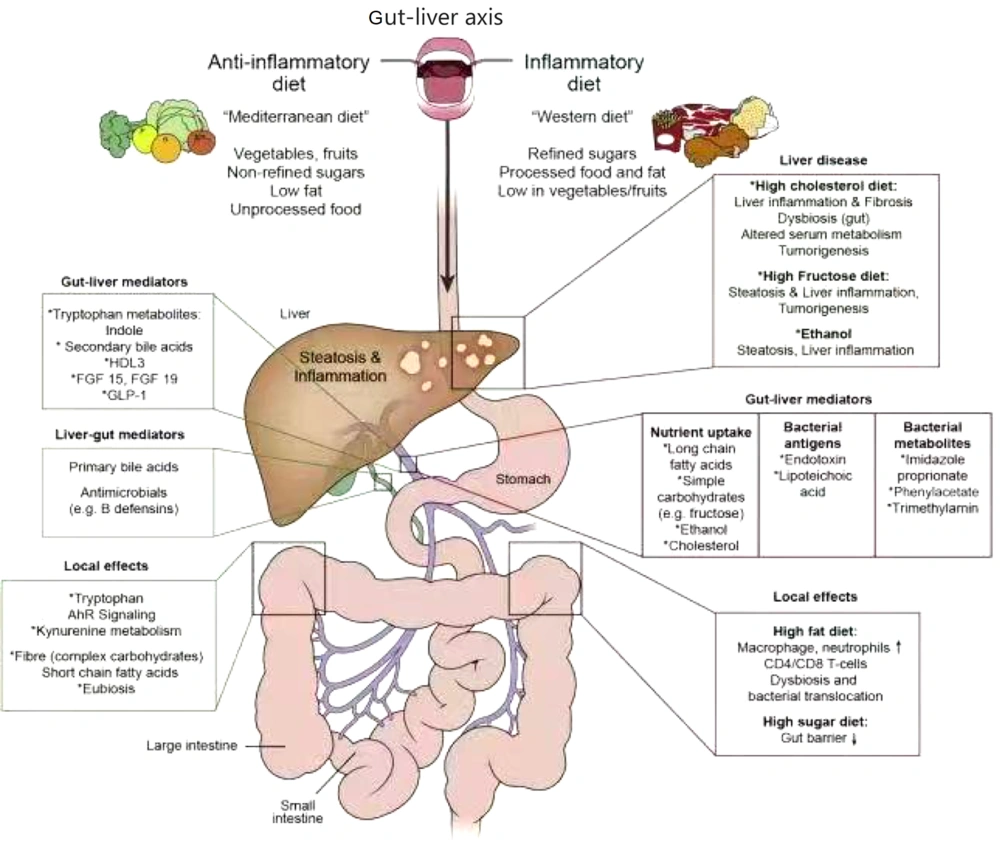

The gut-liver axis constitutes a bidirectional communication network integrating the intestine, gut microbiota, and liver via the portal venous system (Figure 1). Intestinal microbiota and their metabolites serve as pivotal mediators of this axis, and microbial homeostasis and intact intestinal barrier function are essential for maintaining hepatic immune tolerance (2). Under physiological conditions, minimal quantities of dietary antigens, commensal bacteria, and toxins traverse the portal circulation to the liver, triggering immune surveillance and detoxification. Concurrently, bile acid homeostasis, which is regulated through the dual mechanisms of hepatic synthesis and intestinal biotransformation, stabilizes the microbial composition, thereby modulating systemic metabolism (e.g., glucose and energy homeostasis) (3).

In pathological states, increased intestinal permeability and dysbiosis disrupt this equilibrium, enabling bacterial overgrowth, pathological translocation, and endotoxemia. These events activate hepatic Toll-like receptors (TLRs), initiating NF-κB signaling cascades and upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α), which drive chronic inflammation, hepatic fibrogenesis, and progression to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (4). The liver, acting as both a metabolic filter and biosynthetic hub, reciprocally modulates the gut microbiota composition via the biliary secretion of antimicrobial peptides and phase II detoxification products. Conversely, microbial metabolites regulate hepatic bile acid synthesis, lipid-glucose metabolism, and innate immune responses through enterohepatic circulation (5).

Emerging evidence highlights the critical role of bile acid signaling in mucosal immunity and carcinogenesis, with Farnesoid X receptor (FXR)-dependent pathways mediating microbiota-host crosstalk across the gut-liver axis (6). Studies have demonstrated that the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids critically governs mucosal colonization resistance and orchestrates both local and systemic innate/adaptive immune responses, with profound implications for tissue homeostasis and carcinogenesis.

1.1.2. Impact of Bile Acids on Gut Microbiota

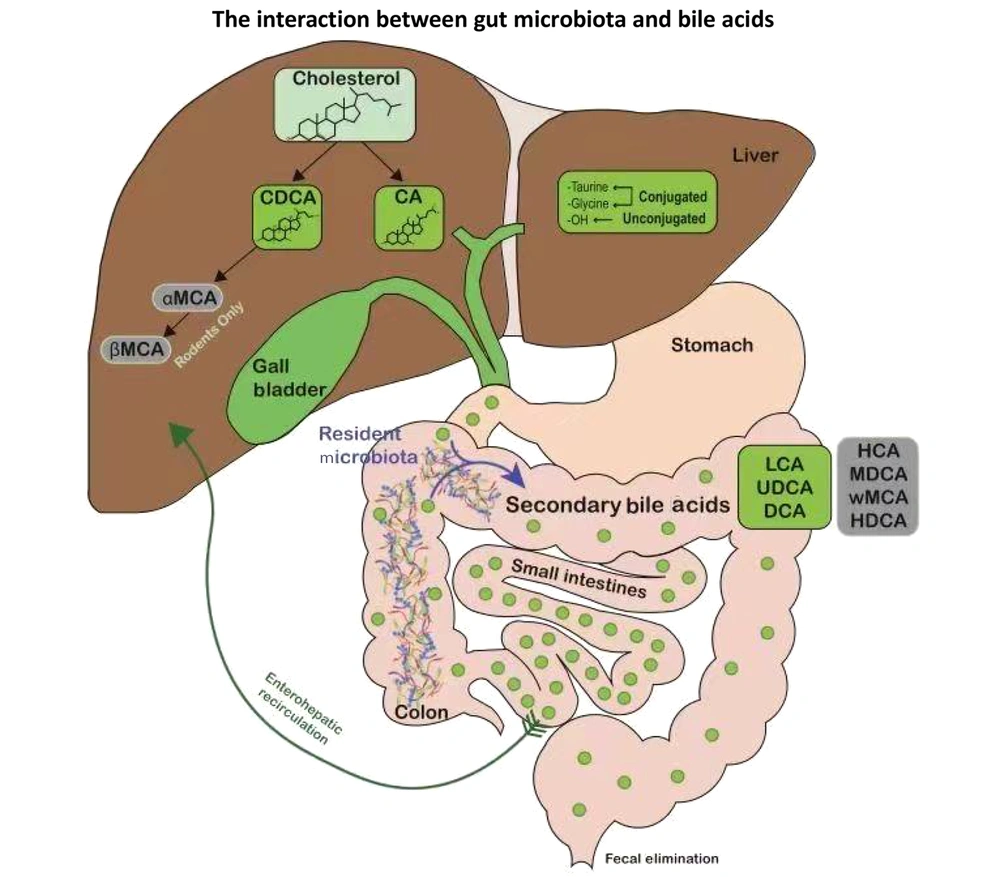

Bile acids play crucial roles in fat digestion, cholesterol metabolism, and gut microbiota regulation. The gut microbiota converts primary bile acids into secondary bile acids, and nearly 95% of bile acids undergo enterohepatic circulation, recycling via the portal vein to the liver (7). This cycle is essential for maintaining intestinal microbial homeostasis and preventing dysbiosis (8). Disruption of the gut microbiota alters bile acid metabolism, affecting its composition and quantity (9). The bile acid receptor FXR is expressed in various tissues, with the liver and ileum being the most studied organs. Research has found that FXR, a bile acid receptor, regulates bile acid synthesis by inducing intestinal FGF19, which inhibits hepatic cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase activity (10, 11). Bile acids possess antimicrobial activity and can inhibit the growth of intestinal bacteria, thereby reshaping the gut microbial community. Bile duct ligation leads to gut microbiota dysbiosis, whereas FXR agonists can maintain the integrity of the intestinal barrier in bile duct-ligated mice and alleviate liver injury (12, 13).

The gut microbiota and bile acids engage in a bidirectional relationship: The microbiota regulate bile acid metabolism via the FXR-FGF19 axis, while bile acids reciprocally shape the microbial composition by promoting bile acid-metabolizing bacteria and suppressing sensitive species, thereby maintaining homeostasis (Figure 2) (14-17). The amphiphilic nature of bile acids allows them to directly exert antimicrobial effects by disrupting bacterial cell membranes, which is crucial for maintaining microbial homeostasis. Studies have found that bile duct ligation for one week can induce bacterial translocation to the mesenteric lymph nodes in rats, and after three weeks, bacterial translocation expands to tissues such as the liver, spleen, and lungs. Concurrently, the number of gram-negative bacteria in the cecum and the level of endotoxins in the blood significantly increased, with flattening of the villi in the distal ileum and enlargement of Peyer's patches (18). Oral administration of bile acids effectively inhibits small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, bacterial translocation, and endotoxemia (19). Secondary bile acids can inhibit the growth of Clostridium difficile, a well-known pathogenic bacterium, thereby resisting infections caused by this bacterium (20). Bile acids can enrich bacteria that can utilize bile acids. For example, bacteria with bile salt hydrolase activity, such as Lactobacillus, can resist the cytotoxicity of bile salts (21). In vitro culture experiments have shown that the growth of Bilophila wadsworthia requires bile acids (22). Studies have found that a diet rich in milk fat can alter the bile acid composition profile, primarily manifested by an increase in taurocholic acid (TCA) levels, and the abundance of B. wadsworthia also increases accordingly (23). In IL-10 knockout mice, oral administration of TCA in a regular diet can promote the growth of B. wadsworthia, and the abundance of this bacterium is associated with the severity of colitis in IL-10 knockout mutant mice (17). This demonstrates that the interaction between bile acids and the microbiota can influence host metabolism. Patients with alcoholic liver disease exhibit changes in the composition and size of the bile acid pool by upregulating bile acid synthesis genes, altering bile acid conjugation enzymes, and modulating bile acid transporters (24). Conversely, dysbiosis of the gut microbiota associated with echinococcosis affects bile acid metabolism, which may be related to the pathogenesis of HAE. In summary, the gut microbiota modulates bile acid metabolism and synthesis through the FXR-FGF19 signaling axis, whereas the homeostatic enterohepatic circulation of bile acids reciprocally stabilizes the gut microbial ecosystem. Dysregulation of either component establishes a pathogenic bidirectional loop that drives the initiation and progression of HAE.

1.2. Mutual Influence Between Intestinal Homeostasis Disruption and Liver Diseases

Intestinal homeostasis can be disrupted by multiple factors, including antibiotic abuse, alcoholism, high-fat diets, hyperglycemia, diseases, infections, and stress. However, in patients with liver disease, the most significant and common cause is the liver disease itself, leading to intestinal homeostasis disruption (25-31). A growing body of research indicates that while liver diseases can induce intestinal homeostasis disruption, the latter also exacerbates liver diseases through enterogenic endotoxemia, driving the further progression of hepatic pathologies (32, 33). The close anatomical and functional connection between the liver and gut, known as the gut-liver axis, creates a unique immune microenvironment in the liver. This axis has garnered increasing attention in the treatment of liver diseases (34). Most intestinal metabolites enter the liver for further breakdown and metabolism, resulting in prolonged hepatic exposure to gut-derived toxins (35). The liver, the largest immune organ in the human body, is rich in immune cells and serves as the primary barrier against gut-derived antigens. Consequently, enterogenic endotoxemia plays a critical role in the initiation and progression of liver disease (36).

Abnormal gut microbiota metabolites, such as reduced SCFAs produced by beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus), diminish their anti-inflammatory and intestinal barrier-supporting functions (e.g., butyrate), leading to impaired gut barrier integrity and aggravated liver injury. Conversely, the accumulation of toxic metabolites, such as ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, produced by opportunistic pathogens (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae), increases the metabolic burden of the liver, promoting the development of hepatic encephalopathy, cirrhosis, and other liver diseases. Multiple liver diseases (e.g., cirrhosis and cholestasis) reduce bile acid secretion, disrupt gut microbiota balance (e.g., decreased Firmicutes and increased Proteobacteria), and elevate the risk of pathogenic bacterial colonization. Liver injury triggers systemic inflammatory cytokine release (e.g., IL-1β and IL-17), further damaging the intestinal epithelial barrier and establishing a "gut-liver inflammatory cycle". Conditions such as portal hypertension in cirrhosis cause intestinal edema and ischemia, exacerbating gut barrier dysfunction and microbial translocation (MT). The interplay between intestinal homeostasis disruption and liver diseases forms a vicious cycle via the microbiota-gut-liver axis, involving compromised barrier function, immune activation, and metabolic dysregulation. Future therapeutic strategies should focus on the integrated modulation of the gut microbiome and hepatic microenvironment to break this pathological cycle.

1.3. Link Between Hepatic Alveolar Echinococcosis and Gut Microbiota

The HAE, caused by the exogenous infiltrative growth of E. multilocularis, lacks a clear fibrous septum between the parasite and host tissue. It primarily originates in the liver, destroying hepatic tissues through compression, erosion, and toxin secretion, leading to liver fibrosis and hepatic dysfunction. Additionally, the parasite can invade the hepatic veins and metastasize to the lungs and brain via the bloodstream. Clinically termed "parasitic cancer", HAE has an extremely poor prognosis. Emerging studies suggest that alterations in the gut microbiota may play a critical role in the pathogenesis and progression of HAE.

In healthy individuals, the gut microbiota is predominantly composed of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria (37). These bacteria communicate with distant organs through metabolites, linking microbial activity to host physiological functions, such as immune regulation, endocrine signaling, neural modulation, and metabolic homeostasis (38). Relevant studies have found significant changes in the intestinal flora after Echinococcus infection. For example, the relative abundance of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria increases, while the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes decreases (39-41). Significant dysbiosis in gut microbiota has been reported in HAE patients. Comparative analyses reveal distinct differences in gut microbial composition between HAE patients and healthy individuals:

- The HAE patients: Dominant bacteria include Proteobacteria, Escherichia, and Eubacterium.

- Healthy individuals: Dominant bacteria include Oxalobacter, Bilophila, and Eubacterium.

Notably, Escherichia and Eubacterium exhibit higher relative abundance in HAE patients, while Bifidobacterium, Eubacterium, and Coprococcus are more prevalent in healthy populations (1). The gut microbiota composition in patients with HAE significantly differs from that of healthy individuals.

Regarding the mechanisms by which gut microbiota influences HAE pathogenesis, studies suggest two key pathways: (1) Microbial antigens or antigen mimicry may directly activate antitumor T cells, inducing immunogenic cell death and (2) microbes can modulate the hepatic microenvironment by engaging pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to regulate immune responses (42, 43).

Importantly, the role of the microbiome extends beyond the mere presence of microbes. Their derivatives and metabolites, such as bile acids, also play critical roles in shaping immune cell infiltration and stimulating immunosuppressive pathways (44). These interactions highlight the complex interplay between the gut microbiota, host immunity, and disease progression in HAE.

1.3.1. Necessity of Understanding Echinococcus multilocularis and Microbial Features of Infection Lesions

The infiltration of immune cells in liver tissues is influenced by the gut-liver axis and, consequently, by the gut microbiota. The complex biodiversity of the gut microbiota plays a critical role in the pathogenesis, progression, and local microenvironment of liver disease (45). However, the microbial characteristics of the parasite lesions and surrounding tissues during HAE development remain poorly understood. Their potential as early diagnostic biomarkers and their impact on the immune microenvironment of echinococcosis remain unclear.

Significant progress has been made in the study of intratumoral and tissue-specific microbes. For example, researchers from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center reported in "Cell" on the role of intratumoral microbes in pancreatic cancer prognosis. Subsequently, the team identified microbial dysbiosis and polyamine metabolism-based biomarkers for the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer (46). In 2020, Israeli scientists published groundbreaking findings in the journal "Science", revealing the presence of abundant microbes within malignant tumors, such as breast, lung, pancreatic, bone, and brain cancers. They demonstrated that the composition and abundance of intratumoral microbiomes correlated with tumor characteristics and treatment outcomes. The team further discovered that dietary fiber and probiotics modulate gut microbiota and influence responses to melanoma immunotherapy (47), laying the foundation for the use of antibiotics as predictive markers for immunotherapy sensitivity (48).

Building on these advances in cancer research, it is plausible to hypothesize that elucidating the microbial communities within and around E. multilocularis lesions could provide novel biomarkers for the early diagnosis and prognosis of HAE. Such insights may also pave the way for personalized therapeutic strategies tailored to host-microbe-parasite interactions.

1.3.2. Gut Microbiota Translocation in Hepatic Alveolar Echinococcosis

Patients with liver disease exhibit increased gut bacterial translocation and circulating bacterial DNA levels, suggesting that certain pathogens may originate in the gastrointestinal tract (49). Gut microbiota translocation and the ability to bypass the intestinal mucosal barrier are distinct mechanisms that play critical roles in the emergence of systemic infections during decompensated liver function (50). Intestinal bacteria, such as Escherichiacoli, Proteus, and Enterobacter, were found to increase the incidence of bacteremia in sterile mice because these intestinal bacteria were more prone to translocation than anaerobic bacteria. Other researchers compared the fecal and salivary bacterial compositions of 102 patients with cirrhosis (43 of whom were diagnosed with hepatic encephalopathy) and 32 healthy individuals. They found a significant difference in the composition of salivary bacteria in patients with cirrhosis. In addition, the number of Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcaceae in the saliva of patients with cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy increased significantly (51). Deping et al. (1) used the metagenomic analysis method to study 7 cases of multilocular echinococcosis patients and 6 cases of granulose echinococcosis patients as the infection group, and 13 cases of healthy family members of nursing patients as the healthy control group, and found that there were significant differences in intestinal flora between the two groups. This suggests a shift in the intestinal flora of patients with HAE. Shifted foreign bacteria may disrupt the balance of normal intestinal flora, alter the intestinal microbial environment, and further affect the outcome of the disease. In a study comparing the intestinal flora of patients with liver cirrhosis and healthy individuals, it was found that the abundance of bacteria, including A. shahii, Methanobrevibacter smithii, and Streptococcus vestibularis, in the feces of patients with liver cirrhosis was increased. Some bacterial infections (such as Enterobacteriaceae and Streptococcaceae), as well as reductions in beneficial bacteria such as Lachnospiraceae, may affect the clinical manifestations and prognosis of the disease (52). In animal models, the gut microbiota changes significantly during the progression of liver disease. Some scholars have created animal models of liver disease using streptozotocin and a high-fat diet, causing them to develop steatosis, fibrosis, and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma. Dynamic studies have found that bacterial species such as Bacteroides, Atopobium spp., and Desulfovibrio can increase disease progression (53). In summary, intestinal flora may be involved in the occurrence, development, and complications of HAE.

1.4. Summary and Prospect

While the involvement of intestinal flora in the pathogenesis of HAE is increasingly recognized, particularly through its regulation of intestinal metabolism (e.g., bile acid homeostasis) and bacterial components, the clinical application of intestinal microecological modulators remains in its early stages. Current challenges highlight critical gaps requiring further investigation:

1. Individual variability in intestinal flora: Significant differences exist due to factors such as ethnicity, dietary habits, and age, complicating the identification of universal therapeutic targets.

2. Limited clinical progress: Most studies are small-scale and lack long-term follow-up data, hindering the validation of sustained therapeutic effects or the monitoring of disease recurrence.

3. Uncertainty regarding the clinical safety and efficacy of modulators: Existing trials have primarily focused on short-term outcomes, with limited exploration of specific probiotic strains (e.g., Lactobacillus or Bifidobacterium species) or combinations. Safety concerns, such as the risk of bacterial translocation in immunocompromised patients or interactions with conventional therapies (e.g., benzimidazole derivatives), remain to be tested. Additionally, the stability of these preparations under varying storage and administration conditions has not been systematically evaluated.

4. Complexity of molecular mechanisms: The diverse intestinal metabolites (e.g., SCFAs and secondary bile acids) and their interactions with host immunity or parasite survival pathways are poorly characterized, necessitating advanced metagenomic and metabolomic approaches to clarify causal relationships.

With the maturation of metagenomics and metabolomics technologies, future studies should prioritize the expansion of biological sample sizes, standardization of quality control protocols, and identification of representative microbial taxa or metabolic biomarkers correlated with HAE progression. Establishing a dedicated microbial database for HAE could facilitate the screening of highly relevant microorganisms, laying the groundwork for targeted probiotic supplementation and the development of novel preventive and therapeutic strategies.