1. Background

In highly endemic regions such as Asia, the South Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and the Middle East, anti-hepatitis B core (anti-HBc) positivity rates exceed 50%. In regions with moderate prevalence, including the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe, anti-HBc positivity rates range from 10% to 50% (1). Studies in Turkey detected a 4% positivity rate for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and a 30.6% positivity rate for total anti-HBc among adults (≥ 18 years), indicating that Turkey is among the moderate endemicity regions for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (2).

Cytotoxic and immunosuppressive treatments are well-known to reactivate chronic hepatitis B (CHB) in HBsAg-positive cases (3). The HBV reactivation and associated fatal fulminant liver failure have been observed even in HBsAg-negative but anti-HBc IgG-positive individuals (4). To date, numerous clinical guidelines have been developed with the aim of reducing the incidence of hepatitis cases associated with HBV reactivation in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy (1, 4-7). However, in the Asia-Pacific region, where HBV infection is endemic, hepatitis due to HBV reactivation remains a significant health threat leading to acute and chronic liver failure (8). The main reason for this situation is the non-adherence to guidelines by physicians working in medical disciplines other than hepatology and infectious diseases. This situation has become even more complex with the recent rapid spread of the use of new immunosuppressive agents (4).

Corticosteroids (CS) are among the most frequently prescribed immunosuppressive agents; however, they often present a significant dilemma for physicians. These agents have distinct therapeutic effects in treating various diseases, yet they are also associated with a wide spectrum of potential adverse effects that can impact nearly all organ systems. The risk of adverse effects increases when the CS dose exceeds the equivalent of 10 - 15 mg/day of prednisolone (9).

One notable complication is the reactivation of infections such as CHB. The use of CS is considered an independent risk factor for CHB reactivation (10), and the risk is directly proportional to both the duration and the dose of CS therapy. Reports indicate that the likelihood of CHB reactivation significantly increases with CS therapies lasting longer than 2 - 4 weeks and exceeding the equivalent of 20 mg of prednisolone (5, 11).

A study conducted in the United Kingdom reported that CS agents accounted for 0.9% of all prescriptions written by primary care physicians (11). However, the literature provides limited information on this topic, and few studies have investigated the frequency of CS use in either inpatient or outpatient settings.

2. Objectives

This study aims to determine the rates and indications for CS use among inpatients and to highlight the importance of HBV screening, which is often overlooked in clinical practice.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The study employed a point-prevalence, multicenter design. On January 28, 2023, researchers evaluated all inpatients at the participating centers to assess their current treatments and identify those receiving CS therapy. Information regarding HBV-related serologic tests for patients undergoing CS treatment was obtained from medical records, hospital databases, and the Ministry of Health National Electronic Database (e-Pulse).

According to international guidelines, in countries where the prevalence of HBsAg exceeds 2%, healthcare providers should test for HBsAg, anti-HBc IgG, and anti-HBs surface antibodies before initiating any immunosuppressive therapy (1, 4, 5). In this study, ordering all three tests as recommended by the guidelines was defined as adequate screening, while ordering only one or two of the tests was defined as inadequate screening.

The rates of CS use, indications for therapy, and equivalent doses of prednisolone were assessed. Based on HBV serologic test results and the administered CS doses, patients were categorized into risk groups for HBV reactivation. The study defined the prednisolone and prednisone 1 mg equivalent doses as follows: Five mg for cortisone, 4 mg for hydrocortisone, 0.8 mg for methylprednisolone and triamcinolone, 0.12 mg for betamethasone, and 0.15 mg for dexamethasone (12). All international guidelines classify CS doses according to their equivalence to prednisolone. In these guidelines, prednisolone doses exceeding 20 mg/day are considered high-dose, doses between 10 - 20 mg/day are considered medium-dose, and doses below 10 mg/day are considered low-dose CS therapy. The same guidelines define CS treatment lasting 4 weeks or longer as long-term treatment, and CS therapy lasting 1 week or less as short-term treatment (1, 3-6).

The risk groups for CHB reactivation were determined based on the most recent AGA clinical practice guideline on the prevention and treatment of HBV reactivation in at-risk individuals and are categorized as follows (5):

1. High reactivation risk (> 10%): The HBsAg- and anti-HBc-positive patients receiving medium (10 - 20 mg) or high-dose (> 20 mg) prednisolone-equivalent CS for 4 weeks or longer.

2. Moderate reactivation risk (1 - 10%): The HBsAg- and anti-HBc-positive patients receiving low-dose (< 10 mg) prednisolone-equivalent CS for 4 weeks or longer; HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive patients receiving medium (10 - 20 mg) or high-dose (> 20 mg) prednisolone-equivalent CS for 4 weeks or longer.

3. Low reactivation risk (< 1%): The HBsAg- and/or anti-HBc-positive patients receiving low-, medium-, or high-dose CS therapy for less than one week; HBsAg- and/or anti-HBc-positive patients receiving intra-articular CS injections; HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive patients receiving low-dose (< 10 mg) prednisolone-equivalent CS for 4 weeks or longer.

3.2. Statistical Data

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, maximum, frequency, and ratio values. Qualitative independent data were analyzed using chi-square tests. When chi-square test assumptions were not met, Fisher’s exact test was applied. For analyses involving more than two groups, pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Bonferroni correction (13). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information

A total of 22 centers participated in the study. Among 6,818 inpatients aged over 18 years, 725 patients (10.6%) were receiving CS treatment. The mean age of CS users was 62.3 ± 17.1 years (range: 18 - 94 years; median: 66 years), and 419 (57.8%) were male. The average hospital stay was 10.5 ± 13.6 days.

At least one chronic disease was identified in 642 patients (88.6%). The most common chronic comorbidities were pulmonary diseases (61.1%), cardiac diseases (44.0%), diabetes mellitus (22.2%), and malignancy (14.6%). Additionally, 62 patients (8.6%) were receiving another immunosuppressive agent in addition to CS therapy. Further detailed demographic and clinical data are presented in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

Pulmonary diseases, rheumatology, and transplant units had the highest CS usage rates at 47.6%, 40.6%, and 38.5%, respectively. Respiratory diseases (n = 419, 57.8%) and malignancy (n = 45, 6.2%) were the most common indications for CS therapy. A significant proportion of the patient population (n = 485, 66.9%) received CS for one week or less, while 9.1% (n = 66) were treated for more than four weeks (Tables 1 and 2; Appendix 1 in Supplementary File).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Duration of CS use | |

| 1 wk or less | 485 (66.9) |

| 1 - 2 wk | 114 (15.7) |

| 2 - 4 wk | 60 (8.3) |

| 4 wk to 1 y | 41 (5.7) |

| > 1 y | 25 (3.4) |

| Reasons for CS use | |

| Respiratory system diseases | 419 (57.8) |

| Malignancy | 45 (6.2) |

| Postoperative-trauma-antiedema | 45 (6.2) |

| Rheumatological diseases | 43 (5.9) |

| Neurological diseases | 36 (5.0) |

| Organ transplant | 23 (3.2) |

| Haematological diseases | 19 (2.6) |

| Sepsis and infections | 13 (1.8) |

| Other | 47 (6.5) |

| Unknown | 35 (4.8) |

Abbreviation: CS, corticosteroid.

| Variables | Total (N = 725) | Current Screening Presence (N = 560) | P b | Adequate Screening Presence (N = 164) | P c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of CS use (wk) | 0.074 | < 0.001 | |||

| < 2 | 599 (82.7) | 452 (75.5) | 113 (25.0) d | ||

| 2 - 4 | 60 (8.3) | 51 (85.0) | 18 (35.3) d | ||

| > 4 | 66 (9.1) | 57 (86.4) | 33 (57.9) | ||

| Additional immunosuppressive drug | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||

| Present | 62 (8.6) | 60 (96.8) | 41 (68.3) | ||

| Absent | 663 (91.4) | 500 (75.4) | 123 (24.6) | ||

| Department type | < 0.001 | 0.030 | |||

| ID | 471 (65.0) | 341 (72.4) e | 86 (25.2) f | ||

| SD | 113 (15.6) | 92 (81.4) | 14 (15.2) e | ||

| ICU | 141 (19.4) | 127 (90.1) | 31 (24.4) |

Abbreviations: CS, corticosteroid; ID, internal departments; SD, surgical departments; ICU, intensive care units.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b The chi-square test was used between categorical variables.

c The chi-square test was used for categorical variables with adequate screening among those screened.

d Difference from group > 4 weeks P < 0.05.

e Difference from group ICU P < 0.05.

f Difference from group SD P < 0.05.

Methylprednisolone (n = 488, 66.9%), prednisolone (n = 135, 18.6%), and dexamethasone (n = 96, 13.2%) were the most frequently used CS, while hydrocortisone was administered in five cases and betamethasone in one case.

When analyzed in terms of prednisolone-equivalent dose, 497 patients (68.6%) received a high dose (> 20 mg prednisolone equivalent), 135 (18.6%) received a medium dose (10 - 20 mg prednisolone equivalent), and 93 (12.8%) received a low dose (< 10 mg prednisolone equivalent) of CS. The mean prednisolone-equivalent dose for all patients was 67.2 ± 113.2 mg (range: 2 - 1,250 mg).

In 62 cases (8.6%), an additional immunosuppressive drug was used alongside CS therapy. Among these, 35 patients had received CS treatment for less than one month, while 27 patients had used CS for one month or longer.

4.2. Screening and Reactivation Risk Information

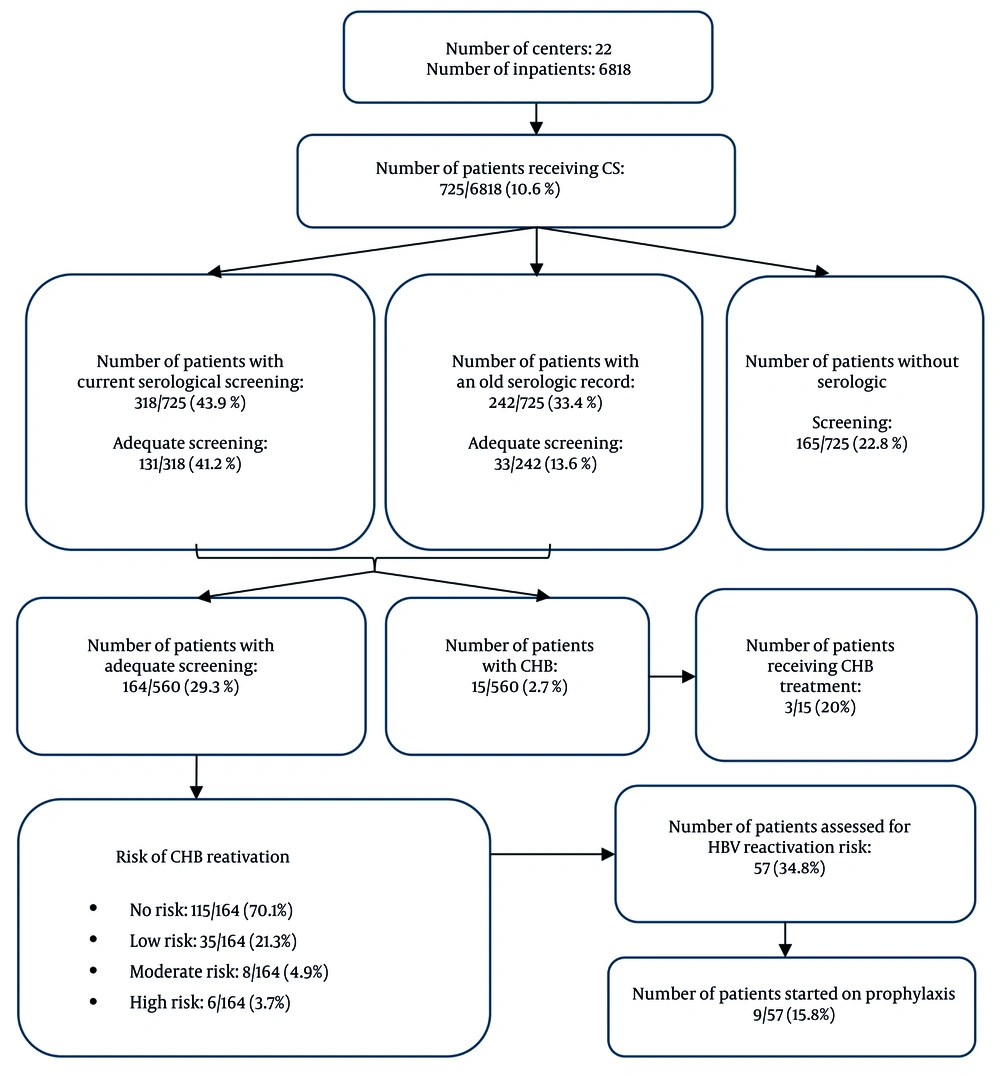

Clinicians evaluated HBV serological markers in 318 patients (43.9%) who received CS during hospitalization. A review of hospital databases and the national e-Pulse system revealed that 560 patients (77.2%) had current or historical HBV serology results, while 165 (22.8%) had no recorded serological tests.

Of all patients, 164 (22.6%) had adequate HBV screening. In 396 cases (54.6%), at least one serologic test result was available but did not fulfill the criteria for adequate screening. Among these partial screenings, 9 patients (2.3%) had only anti-HBs, 94 (23.7%) had only HBsAg, and 293 (74.0%) had both anti-HBs and HBsAg. None of these patients had results for anti-HBc IgG. Examination of the duration of CS use revealed adequate HBV screening rates of 30% (18/60) among patients using CS for 2 - 4 weeks and 50% (33/66) among those using CS for more than one month. Although no statistically significant correlation was found between the duration of CS use and overall serologic screening (P = 0.074), the rate of adequate screening increased as the duration of CS use lengthened (P < 0.001).

We also found that HBV screening rates were higher in patients who received other immunosuppressive agents in combination with CS therapy (P < 0.001). According to clinical department, although overall screening rates were lower in the Department of Internal Medicine, the adequacy of screening was higher than in other departments (P = 0.030, Table 2).

The HBsAg positivity was detected in 15 patients (2.7%), nine of whom had a previously known diagnosis of CHB. Screenings newly identified HBsAg positivity in 6 cases (1.1%). Among patients who underwent adequate screening, 49 of 164 (29.9%) demonstrated anti-HBc positivity. Based on screening results, 6 cases (3.7%) were classified as high risk, 8 cases (4.9%) as moderate risk, and 35 cases (21.3%) as low risk for CHB reactivation among those adequately screened for CS use.

Screening further revealed that 115 patients (70.1%) had no risk of reactivation. When risk groups were analyzed with respect to CHB reactivation, the high-risk group exhibited higher rates of hospitalization days, concurrent immunosuppressive therapy, infectious-disease consultations, HBsAg positivity, and female gender compared with the other groups.

Interestingly, CS treatment doses were significantly higher in the low-risk group, largely because many patients in this group (n = 19/35) received short-term (< 7 days) and high-dose CS therapy for pulmonary diseases. The flow diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the screening and prophylaxis initiation rates among patients receiving CS therapy. Detailed information on risk groups is presented in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

Among 561 patients (77.4%), the evaluation of CHB reactivation risk was inadequate. However, when analyzed based on the duration of CS use, 533 cases (95.0%) involved CS therapy lasting less than one month, suggesting that these patients theoretically belonged to the low-risk or risk-free group, likely due to HBsAg and anti-HBc negativity.

In 165 patients (22.8%), HBV serology had not been checked during the current hospitalization or in past medical records. Notably, nine of these patients (5.5%) were receiving long-term CS therapy, with seven using CS for over one month and two for more than one year.

4.3. Treatment and Prophylaxis Information

Nine patients (1.2%) were receiving HBV prophylaxis — four due to HBsAg positivity and five due to total anti-HBc positivity. Considering the duration of CS use, only 3 patients (4.5%) among those who had been using CS for more than one month (n = 66) received HBV prophylaxis, and all three were HBsAg-positive. In addition, three patients (0.4%) were undergoing HBV treatment. Detailed information is presented in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

5. Discussion

There are limited studies in the literature that highlight the rates of CS use and the importance of CHB screening in patients receiving these medications. This study is unique in addressing both issues concurrently. The CSs are among the most frequently prescribed immunosuppressive agents used across various medical specialties. Clinicians often prescribe these drugs without a specific indication, and their usage frequency and range continue to increase each year (11, 14). However, one of the most concerning adverse effects of CSs — whose side effect profile spans nearly all organ systems — is the reactivation of certain infections, particularly CHB (10).

A UK national study reported that approximately 1% of all patients were using CSs (11). In an international cohort, the United States, Taiwan, and Denmark demonstrated CS use rates of 6.8%, 17.5%, and 2.2%, respectively (14). Cross-sectional data from France showed CS use rates ranging from 14.7% to 17.1% (15). Furthermore, a national cohort study in the United States found that 21.1% of individuals aged 18 - 64 years received at least one CS prescription during a 3-year follow-up period (16). Most of these studies focused on outpatient populations.

Our study assessed point prevalence among inpatients across various hospitals and found that 10.6% of patients were receiving CS therapy. Consistent with prior research, respiratory system diseases were the most common indication for CS use, accounting for 57.8% of all cases (14, 16). Studies suggest that the prevalence of long-term CS use in the general population ranges between 0.5% and 1% (14, 17, 18). In contrast, our study identified long-term CS use in 9.1% of patients. The higher rate observed here may be attributed to the fact that our study focused on inpatients, who generally have more comorbidities than the general population.

The reason for CS use could not be determined in 4.8% of the patients. The literature on this topic is limited; however, one study reported that the indication for CS use was unclear in 20% of cases, which is higher than the rate found in our investigation (11).

The HBV reactivation is a necroinflammatory liver disease characterized by increased viral replication in patients with resolved CHB infection or HBeAg-negative CHB. The HBV reactivation can occur under immunosuppressive conditions, due to drug-induced factors, or spontaneously. In such cases, the surge in viral replication can lead to liver injury during immune reconstitution. Therefore, in countries where the prevalence of HBsAg exceeds 2%, healthcare providers are recommended to perform HBsAg, anti-HBc IgG, and anti-HBs testing prior to initiating any immunosuppressive therapy (1, 3, 4).

Despite these recommendations, HBV screening remains insufficient. A large-scale study conducted at a U.S. cancer center found that only 16.2% of patients were screened for HBV before starting immunosuppressive therapy (19). Another cancer center reported a relatively higher screening rate of 55% (20). In a national study of rheumatology patients in the United States, researchers observed an adequate screening rate of 28.8%, while 55.2% of patients received no screening, and 16.0% received incomplete screening (21).

In Turkey, Celik et al. reported that among oncology patients, HBsAg screening rates reached approximately 99%, whereas requests for anti-HBc testing were markedly lower at 40% (22). Another multicenter study revealed that physicians prescribing immunosuppressive agents ordered anti-HBc testing far less frequently than HBsAg testing (97% vs. 63%) (23).

A common feature among these studies is their retrospective design and their focus on patients receiving immunosuppressive therapies other than CS. In contrast, our study employed a point-prevalence design, focusing specifically on patients receiving CS therapy, thereby addressing an underexplored area in the literature.

Although Turkey is an endemic country for HBV, our study findings align with the low screening rates reported in the literature. To date, we found no studies specifically addressing HBV screening rates among patients receiving CS therapy. In our research, 23% of cases lacked HBV screening, and only 22.6% of all patients met the criteria for adequate screening. Among those adequately screened, 29.9% demonstrated HBsAg and/or anti-HBc positivity, identifying them as at risk for HBV reactivation. The anti-HBc positivity rate in Turkey is 30.6%, and our findings closely correspond to national data (2). In contrast, U.S.-based research reported a 14.2% rate among screened cases (20).

Our results underscore the importance of developing a “CS management model” to address this gap. The “electronic alert system” implemented by Koksal et al. (24) in cancer patients provides a valuable example. This system markedly improved screening rates — from 55.1% to 93.1% for HBsAg and from 4.3% to 79.4% for anti-HBc IgG. Similarly, a comparable electronic alert system could be developed for patients prescribed CS therapy. Such an alert could increase HBV screening frequency and prompt timely infectious disease consultations for patients initiating CS treatment. An example algorithm for this proposed electronic model is presented in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

One limitation of our study is that it presents the distribution of HBV reactivation risk groups somewhat optimistically. This is because it was conducted as a real-life point prevalence study. As treatment continues, short-term CS users may transition from the low-risk group to intermediate or high-risk groups, shifting the overall risk distribution in a less favorable direction. Another limitation is that routine screening data from surgical clinics were included in our study. It is known that routine preoperative HBV screening practices exceed 85% in our country (25, 26). Because our research design was point prevalence–based, any test ordered for any reason was considered as adequate screening. Under these circumstances, it is evident that screening performed solely due to CS initiation is far lower than what our findings indicate. Furthermore, many HBsAg and/or anti-HBc IgG-positive patients did not receive infectious disease consultations despite being on immunosuppressive therapy, supporting our interpretation.

In conclusion, our study highlights the high rate of CS use and inadequate screening for CHB prophylaxis, both of which are noteworthy. Similar findings have been reported in studies from the United States and Europe. However, despite Turkey’s endemic HBV status, the limited attention to this issue among healthcare professionals remains a serious concern.