1. Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) chronically infects approximately 296 million individuals worldwide, leading to over 820,000 deaths annually due to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (1). The primary goal of antiviral therapy for HBV is the long-term suppression of HBV DNA replication. The ideal therapeutic endpoint is the sustained clearance of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) (2). Achieving this endpoint significantly reduces the risk of HCC and liver-related mortality, improves overall survival, and delays disease progression (3).

Nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs), including entecavir (ETV), tenofovir alafenamide hemifumarate (TAF), and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), potently inhibit HBV DNA polymerase (4, 5). However, long-term NA therapy has limited efficacy in achieving HBsAg clearance, especially in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients with baseline HBsAg levels > 1500 IU/mL. Due to insufficient immune activation, these patients are often referred to as a “non-optimal population” for antiviral treatment (6).

Pegylated interferon-alpha (PEG-IFN-α), through both antiviral and immunomodulatory actions, has been proposed as an effective sequential or add-on strategy. Recent studies suggest that combination regimens with PEG-IFN-α may enhance the rate of HBsAg loss or seroconversion in NA-suppressed CHB patients (7, 8). Nonetheless, treatment responses vary considerably, and the efficacy in patients with high baseline HBsAg levels remains insufficiently characterized (9).

2. Objectives

Currently, limited studies, to the best of our knowledge, exists on the factors influencing HBsAg response and guiding the selection of patients most likely to benefit from sequential PEG-IFN-α therapy. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore optimized treatment strategies and identify determinants of HBsAg response in this population.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Patient Enrollment

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at Sanmen People’s Hospital, Sanmen, China on CHB patients treated between July 2021 and July 2024. Eligible patients met the following criteria: Age ≥ 18 years, ≥ 1 year of NAs treatment, HBsAg > 1500 IU/mL, HBV DNA < 20 IU/mL, and complete clinical data. Patients with other viral hepatitis, severe extrahepatic diseases, or contraindications to interferon were excluded. A total of 85 patients were included: Thirty-five received PEG-IFN α-2b plus NAs (study group), and 50 received NAs alone (control group). The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was based on the combination of clinical manifestations (such as abnormal liver function and portal hypertension), imaging and endoscopy, and laboratory findings. Liver biopsy was performed in patients with a difficult diagnosis. Treatment allocation was based on physician and patient preference rather than randomization, due to the retrospective nature of the study. Potential confounding factors (e.g., baseline HBsAg, age, cirrhosis) were balanced between groups and adjusted for in the GEE model.

3.2. Treatment Regimen

The study group received PEG-IFN α-2b (180 μg/week, subcutaneously) plus ongoing NA therapy for 48 weeks. The control group continued NA monotherapy for the same duration. Laboratory tests (HBsAg, ALT, and HBV DNA) were performed every 12 weeks. The HBsAg detection was standardized throughout the study period: The same brand of chemiluminescent immunoassay kit (Roche Diagnostics, Cobas®) was used, and all operations followed the manufacturer’s standard protocol. The detection instrument was calibrated quarterly to ensure consistency of results.

3.3. Efficacy Evaluation

Treatment efficacy was defined as either ≥ 1 log10 IU/mL reduction in HBsAg level or HBsAg seroconversion at week 48. Although HBsAg loss is the ideal endpoint, a decline of ≥ 1 log10 IU/mL was chosen as a clinically meaningful surrogate marker for immune reactivation in this high-HBsAg population, as it has been associated with improved long-term outcomes. The HBsAg reduction rate = (baseline - post-treatment HBsAg)/baseline × 100%.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (IQR) and compared using t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-square test. A generalized estimating equation (GEE) model assessed group, time, and interaction effects on HBsAg, with Z-score standardization. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. An exchangeable correlation structure was assumed in the GEE model to account for within-subject correlations over time. No missing data of key laboratory indicators (HBsAg, ALT, and HBV DNA) were observed during follow-up, as only patients with complete clinical data were enrolled. Patients with missing laboratory data at specific time points were excluded from the corresponding time-point analysis. Given the low proportion of missing data, no imputation was performed. Sensitivity analyses excluding these patients yielded results consistent with the main analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics

No notable distinctions were observed between the two groups in terms of gender, age, baseline HBsAg levels, proportion of patients with cirrhosis, and proportion of patients receiving different NA regimens (including ETV, TAF, TDF, ETV+TAF) (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Variables | NAs Therapy Alone (n = 50) | Sequential Therapy with Peg-IFNα-2a and NAs (n = 35) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.363 | ||

| Male | 25 (50.00) | 21 (60.00) | |

| Female | 25 (50.00) | 14 (40.00) | |

| Age | 47.76 ± 8.55 | 45.17 ± 10.23 | 0.209 |

| NA regimens | 0.302 | ||

| ETV | 33 (66.00) | 18 (51.43) | |

| TAF | 15 (30.00) | 12 (34.29) | |

| TDF | 1 (2.00) | 3 (8.57) | |

| ETV+TAF | 1 (2.00) | 2 (5.71) | |

| NAs duration (y) | 5 (3, 7) | 3 (2, 6) | 0.056 |

| HBsAg (IU/mL) | 3500.06 (2184.85, 5317.78) | 2628.01 (2125.48, 5562.77) | 0.728 |

| HBsAb (IU/mL) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.24) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.35) | 0.094 |

| HBeAg (IU/mL) | 0.51 (0.22, 6.40) | 0.57 (0.21, 6.82) | 0.982 |

| HBeAb (IU/mL) | 1.31 (0.01, 2.16) | 0.33 (0.01, 2.13) | 0.467 |

| ALT (IU/mL) | 21.00 (15.00, 26.75) | 25.00 (17.00, 41.00) | 0.110 |

| Cirrhosis | 8 (16.00) | 2 (5.71) | 0.147 |

Abbreviations: NAs, nucleos(t)ide analogs; PEG-IFN-α, pegylated interferon-alpha; ETV, entecavir; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

a Data are presented as No. (%), mean ± SD or median (IQR).

b Comparisons by Mann-Whitney U test or χ2 test.

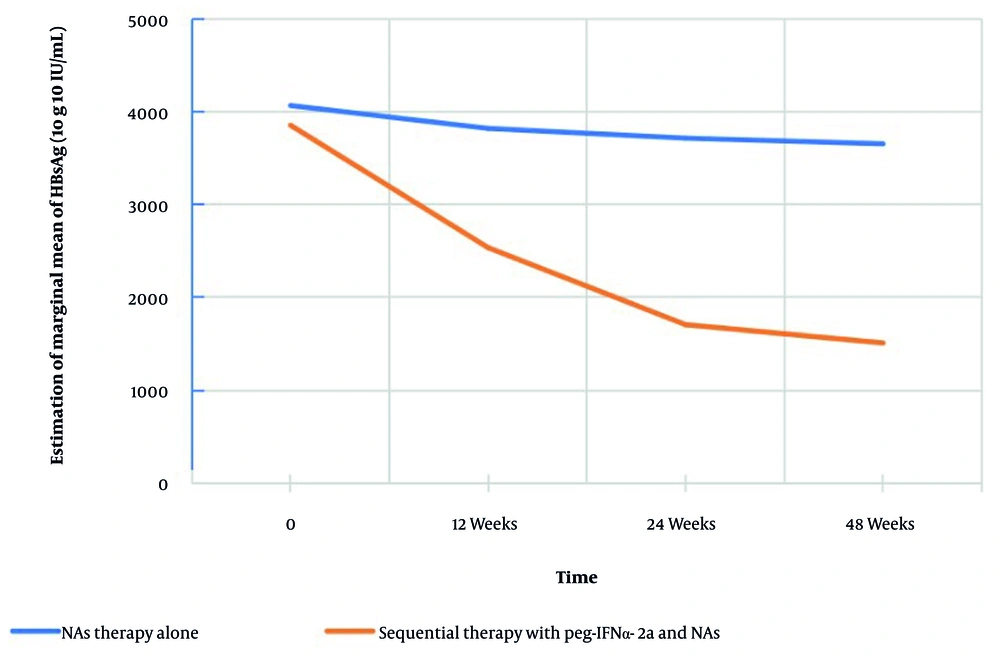

4.2. Enhanced Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Reduction and Clinical Response

At week 48, 8 patients (22.86%) in the study group achieved the defined treatment response (HBsAg decline ≥ 1 log10 IU/mL), while no patients in the control group met the criteria (P < 0.001) (Table 2). The median HBsAg decline rates in the study group at 12, 24, and 48 weeks were 43.92%, 63.68%, and 84.55%, respectively, significantly higher than those in the control group (2.86%, 5.95%, and 11.02%; all P < 0.001) (Table 2). Consistent with this, HBsAg levels in the study group decreased from 3,852.85 IU/mL at baseline to 1,511.19 IU/mL at week 48 (over 60% reduction), while the control group showed only a ~ 10% reduction (from 4,065.23 IU/mL to 3,653.56 IU/mL) (Figure 1).

| Outcome HBsAg Decline (%; wk) | NAs Therapy Alone (n = 50) | Sequential Therapy with Peg-IFNα-2a and NAs (n = 35) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 2.86 (-1.44, 8.61) | 43.92 (18.69, 69.60) | < 0.001 |

| 24 | 5.95 (-2.47, 13.05) | 63.68 (33.10, 94.15) | < 0.001 |

| 48 | 11.02 (-0.58, 16.88) | 84.55 (63.10, 99.12) | < 0.001 |

| Response at 48 b | 0 (0.00) | 8 (22.86) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; NAs, nucleos(t)ide analogs; PEG-IFN-α, pegylated interferon-alpha.

a Data presented as No. (%) or median (IQR).

b Response defined as HBsAg decline ≥ 1 log10 IU/mL. Comparisons by Mann-Whitney U test or χ2 test.

4.3. Validation of the Time-Dependent Advantage of Combined Therapy Using the Generalized Estimating Equations Model

The GEE modeling revealed significant effects of treatment group (P = 0.004), time (P < 0.001), and group × time interaction (P < 0.001) on HBsAg reduction (Tables 3 and 4; Figure 1).

- Early phase (0 - 12 weeks): Rapid HBsAg decline in the combination group (OR = 0.35, P < 0.001).

- Mid to late phase (12 - 48 weeks): Decline continued, though the rate gradually slowed. Cumulative median HBsAg reductions reached 43.92%, 63.68%, and 84.55% at weeks 12, 24, and 48, respectively.

| Effect | Wald χ2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Group | 8.206 | 0.004 |

| Time | 51.307 | < 0.001 |

| Group×time | 28.492 | < 0.001 |

a Dependent variable: Z-score standardized HBsAg. Effects tested via Wald chi-square.

| Parameters | β (SE) | Wald χ2 | P-Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -0.847 (0.162) | 27.333 | < 0.001 | 0.43 (0.31 - 0.59) |

| Group (ref: NA monotherapy) | ||||

| PEG-IFN+NAs | 0.983 (0.198) | 24.785 | < 0.001 | 2.67 (1.82 - 3.94) |

| Time (ref: 48 wk) | ||||

| Baseline | 1.218 (0.208) | 34.398 | < 0.001 | 3.38 (2.25 - 5.08) |

| 12 | 0.529 (0.122) | 18.754 | < 0.001 | 1.70 (1.34 - 2.16) |

| 24 | 0.238 (0.108) | 4.833 | 0.028 | 1.27 (1.03 - 1.57) |

| Group×time interaction (wk) | ||||

| PEG-IFN+NAs×12 | -1.048 (0.218) | 23.134 | < 0.001 | 0.35 (0.23 - 0.54) |

| PEG-IFN+NAs×24 | -0.461 (0.129) | 12.837 | < 0.001 | 0.63 (0.49 - 0.81) |

| PEG-IFN+NAs×48 a | -0.213 (0.113) | 3.568 | 0.059 | 0.81 (0.65 - 1.01) |

a Values include β (SE), OR (95% CI), and significance levels. Interaction terms reflect PEG-IFN effects at each timepoint; 48-week NA group used as reference.

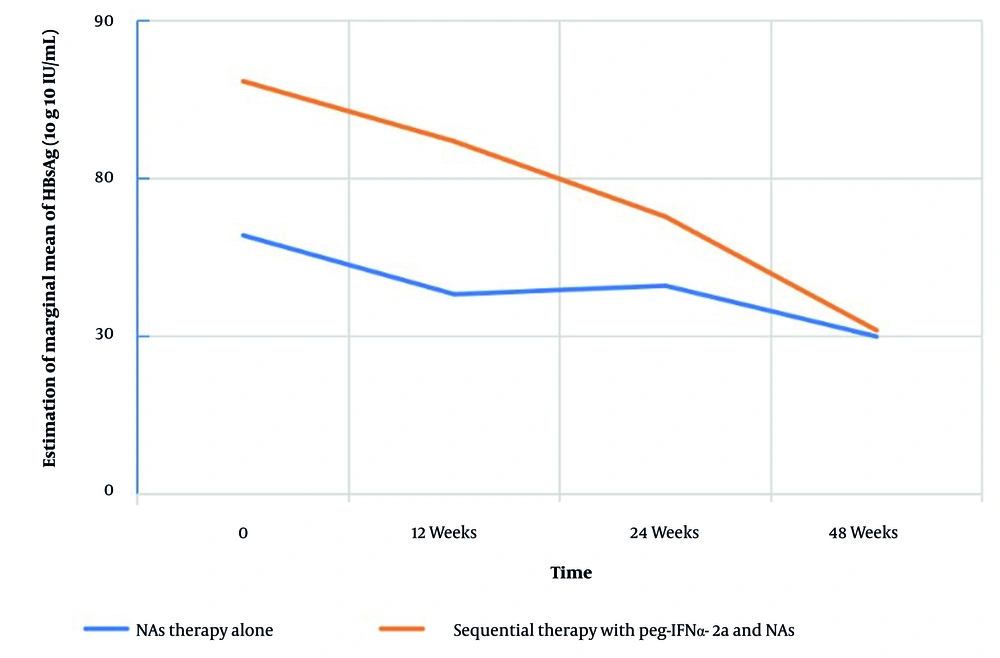

A secondary GEE model showed a modest time effect on HBeAg levels (P = 0.042) but no significant group effect (P = 0.583; Tables 5 and 6; Figure 2). The HBeAg levels remained stable across timepoints in both groups, suggesting limited utility as a response marker in this population.

| Effects | Wald χ2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Group | 0.301 | 0.583 |

| Time | 8.192 | 0.042 |

a Dependent variable: Z-score standardized HBeAg.

| Parameters | β (SE) | Wald χ2 | P-Value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.111 (0.228) | 0.240 | 0.624 | 1.12 (0.72 - 1.75) |

| Group (ref: NA monotherapy) | ||||

| PEG-IFN+NAs | -0.156 (0.399) | 0.153 | 0.696 | 0.86 (0.39 - 1.87) |

| Time (ref: 48 wk) | ||||

| Baseline | -0.026 (0.092) | 0.078 | 0.780 | 0.98 (0.81 - 1.17) |

| 12 | -0.007 (0.068) | 0.009 | 0.923 | 0.99 (0.87 - 1.14) |

| 24 | -0.016 (0.064) | 0.058 | 0.810 | 0.99 (0.87 - 1.12) |

a Values reported as β (SE), OR (95% CI), and P-values.

5. Discussion

This study confirms that for CHB patients with high baseline HBsAg (> 1500 IU/mL) under virological suppression with NAs, adding PEG-IFN leads to a more pronounced HBsAg decline compared to continued NA monotherapy. The combination therapy yielded substantially higher HBsAg reduction rates (median 84.55% vs. 11.02% at week 48) and clinical response rates (22.86% vs. 0%), with a significant time-dependent effect (GEE group×time interaction P < 0.001; OR = 2.67).

At the mechanistic level, persistent antigen stimulation in chronic HBV infection leads to T cell exhaustion and impaired memory T cell development (10). The PEG-IFN activates the JAK-STAT pathway via the IFNAR receptor, induces interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), enhances NK cell activation, increases HBsAg-specific antibody production, and restores HBV-specific CD8+ T cell function (11, 12). Concurrently, NAs reduce viral replication and antigen load, potentially alleviating immune exhaustion and establishing a more favorable environment for immune reconstitution (13). Consistent with this, the study group showed significantly greater HBsAg reduction and a higher proportion of patients achieving HBsAg ≤ 100 IU/mL compared with the monotherapy group (14), highlighting that profound viral suppression by NAs may optimize the immunomodulatory setting for PEG-IFN therapy.

Furthermore, this study is the first to quantify the time-dependent effect of sequential therapy in this population using a GEE model. Both the group main effect (P = 0.004) and the group×time interaction (P < 0.001) support the cumulative benefit of extended treatment duration. The combination regimen showed the greatest advantage within the first 12 weeks and maintained superiority throughout 48 weeks. These findings align with the hypothesis that prolonged therapy may benefit patients with partial early responses, and they provide mathematical support for a staged decision framework:

- 12 weeks: If HBsAg reduction is < 10% (IQR: 18.7 - 69.6% in the study group), it indicates poor response, and alternative strategies (such as adding immunomodulators) may be considered.

- 24 weeks: The median reduction is 63.7% (IQR: 33.1 - 94.2%), a key point for evaluating the value of continued therapy.

- 48 weeks: If HBsAg reduction is ≥ 1 log10 IU/mL (22.86% efficacy in the study group), extending therapy to 72 weeks may be recommended to achieve HBsAg clearance.

This proposed framework is exploratory and requires validation in prospective studies before clinical application. Additionally, this study evaluated the longitudinal changes in HBeAg levels as a secondary outcome. While time showed a mild effect on HBeAg dynamics, PEG-IFN sequential therapy did not significantly influence HBeAg levels, as confirmed by GEE modeling (Tables 4 and 6). This suggests that HBeAg may not be a reliable marker for monitoring therapeutic efficacy in patients with high HBsAg undergoing PEG-IFN add-on therapy. The lack of significant HBeAg decline may be attributed to the predominance of HBeAg-negative patients in our cohort and the generally low baseline HBeAg levels, which limit its utility as a response marker in this population.

5.1. Conclusions

For NA-suppressed CHB patients with high baseline HBsAg (> 1,500 IU/mL), PEG-IFN add-on therapy significantly enhances HBsAg decline and clinical response rates compared to NAs monotherapy, with efficacy escalating over time. Treatment extension guided by dynamic HBsAg changes is warranted to optimize outcomes. This study provides evidence-based preliminary support for managing this “non-advantaged population”. However, due to the retrospective nature and limited sample size, these findings should be interpreted cautiously and validated in prospective trials before being applied as a routine clinical recommendation.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

The limitations of this study include:

1. Its retrospective, single-center design and the non-randomized treatment allocation based on physician and patient preference may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of our findings. Differences in HBV genotypes, ethnic backgrounds, and healthcare settings could further influence treatment responses, underscoring the need for external validation in larger, multi-center, prospective cohorts.

2. The absence of HBV genotyping represents a significant constraint, as the response to interferon is known to vary by genotype. This limits our ability to interpret the interferon response profile within our cohort and to identify patients most likely to benefit from this strategy.

3. Immune-related markers (e.g., IP-10, CD8+ T cell counts, and other exhaustion markers) were not assessed. The lack of these mechanistic data restricts a deeper exploration of the immunomodulatory effects of sequential therapy and the biological determinants of treatment efficacy.

4. The relatively small sample size, particularly the low proportion of cirrhotic patients, reduces statistical power for subgroup analyses and necessitates confirmation in larger populations.

5. Safety data on PEG-IFN-related adverse events were not systematically collected in this retrospective study. Consequently, we cannot report on treatment tolerability, side-effect profiles, or dropout rates, which are critical for evaluating the clinical utility of this regimen.

6. The follow-up period was limited to 48 weeks, preventing the evaluation of long-term outcomes such as sustained HBsAg seroclearance, durability of response, and ultimate clinical impact on liver-related events.

Future studies incorporating multi-omics profiling, HBV genotyping, immune correlates, and extended follow-up are warranted to develop predictive models for optimizing patient selection and to better define the long-term clinical benefit of sequential therapy.