1. Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV), a small enveloped virus and part of the hepatotropic DNA virus family, was identified as a viral infection of the liver causing acute and chronic liver disease, and even further hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (1, 2). Although effective vaccines and antiviral therapy are currently available, chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection remains a critical public health problem worldwide (3-5). According to the latest data from the World Health Organization, by 2022, there will be an estimated 254 million people living with chronic HBV infection; up to 1.1 million patients will die each year from HBV-associated cirrhosis, liver failure, and HCC (6). Accumulating evidence indicates that early diagnosis and treatment of CHB infection are crucial for reducing morbidity and mortality. Currently, there are two different treatment strategies for patients with CHB infection: Therapies of finite duration using immunomodulators such as pegylated interferon-α (PEG-IFN-α), as well as long-term treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs), including entecavir (ETV), tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (7, 8). It is important to note that the standard medication for CHB functional cure is combination therapy consisting of viral DNA polymerase inhibitors and immunomodulators, as recommended by the latest expert consensus (9).

Combination therapy with NAs and IFN can exert synergistic effects, further reducing HBV DNA and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) levels (10-12). The TDF is one of the most commonly used first-line NAs drugs in clinical practice, which competitively binds to the active site of HBV DNA polymerase, thereby inhibiting the activity of viral reverse transcriptase (10). This rapidly reduces the viral load and improves liver function, creating more favorable conditions for IFN to exert its immunomodulatory effects (13). The PEG-IFN-α promotes the clearance of HBV-infected hepatocytes and achieves serological conversion in HBV-infected individuals through its dual actions of activating antiviral proteins and modulating the immune response (14, 15). Moreover, combination therapy may reduce the incidence of drug resistance and maintain more durable virological responses after treatment discontinuation (9, 16). However, the specific mechanisms underlying combination therapy are still unclear and require further investigation.

In the context of chronic HBV infection, the effective and coordinated functioning of innate and adaptive immune mechanisms is of critical importance for successful disease management. During the early phases of HBV infection, the intrinsic immune response is pivotal, subsequently activating the adaptive immune response; the clearance of HBV is predominantly reliant on the immune system's ability to target the virus (17-26). According to a previous study, clinical cure rates surpassed 50% with a reduction in HBsAg by more than 0.5 Log IU/mL at 12 weeks, or a significant decrease in HBsAg levels by over 1 log IU/mL at 24 weeks (27). Moreover, a meta-analysis demonstrated a considerable difference in HBsAg loss and seroconversion between NAs and PEG-IFN-α monotherapy following 24 weeks of treatment, yet no difference was noted after 48 weeks (20). To sum up, these findings suggest that combination therapy at both 12 weeks and 24 weeks can enhance the antiviral response by boosting immune activity, and the extent of HBsAg decline serves as a strong predictor of achieving clinical cure. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism underlying the substantial reduction in HBsAg levels following 12 and 24 weeks of combined treatment remains to be elucidated.

Comparative proteomic methodologies that integrate data-independent acquisition (DIA)-based liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) are frequently employed to investigate host responses in plants, animals, and humans during viral infections (28-31). Furthermore, DIA-based quantitative proteomics serves as a valuable tool for the screening and identification of key protein biomarkers pertinent to early disease detection, diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment (28, 31). Consequently, serum proteomic analysis offers a comprehensive understanding of host factors involved in viral infections and elucidates alterations in signaling pathways, thereby enhancing our comprehension of the molecular pathogenesis associated with HBV infection. Nevertheless, the application of proteomics technology to analyze the differences in serum protein profiles of CHB patients before combined therapy, at 12 weeks of treatment, and at 24 weeks of treatment has not been reported.

2. Objectives

To this end, we conducted a comparative analysis of serum expression profiles in CHB patients prior to and following combination therapy. The findings of this study have the potential to enhance comprehension of serum molecular alterations during various phases of combination therapy, thereby furnishing essential information for future research endeavors into the underlying molecular mechanisms.

3. Methods

3.1. Patients and Sample Collection

Serum samples for this study were collected from patients with CHB who attended the First Hospital of Jiaxing city, the designated facility for viral hepatitis in Jiaxing, between December 2021 and June 2023. The enrolled CHB patients satisfied the diagnostic criteria specified in the 2022 edition of the Guidelines, which include: (1) Voluntary selection of the combination treatment regimen, completion of a treatment period of at least one year for TDF, and initiation of PEG-IFN-α sequential treatment for the first time; (2) an age range of 18 to 65 years; (3) HBsAg levels below 1500 IU/mL, HBV DNA levels below 30 IU/mL, and negative HBeAg status; and (4) achievement of HBsAg clearance (HBsAg < 0.05 IU/mL) or HBsAg seroconversion (HBsAg < 0.05 IU/mL and hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) ≥ 10 IU/L) following 24 weeks of treatment (16). Patients with the following conditions within six months prior to enrollment were excluded from the study: Other forms of viral hepatitis, decompensated liver disease, primary HCC or other malignancies, autoimmune or immune-mediated disorders, organ transplantation, metabolic diseases (e.g., hyperthyroidism, diabetes mellitus), pregnancy, neuropsychiatric abnormalities, and severe organ failure. Relevant clinical data of the anonymized patients are presented in Table 1. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study. The research was conducted in strict accordance with the study protocol, which was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University (ethics approval number: 2022-KY-330), and adhered rigorously to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to the commencement of the study.

| Clinical Indicators | F-P Group | S-P Group | T-P Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Male | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Age (y) | 41.04 ± 9.29 | 41.04 ± 9.29 | 41.04 ± 9.29 |

| HBsAg (IU/mL) | 113.61 ± 169.89 | 23.45 ± 53.39 b | 0.46 ± 0.63 c |

| HBsAb (IU/L) | 1.39 ± 1.63 | 1.59 ± 2.49 | 25.33 ± 74.73 |

| HBeAb (S/CO) | 0.20 ± 0.41 | 0.24 ± 0.46 b | 0.25 ± 0.43 |

| HBcAb (S/CO) | 8.92 ± 0.89 | 8.55 ± 0.76 b | 8.36 ± 1.18 c |

| HBcAb IgM (S/CO) | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.06 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 31.80 ± 27.68 | 62.16 ± 57.41 b | 55.88 ± 38.22 c |

| AST (IU/L) | 26.08 ± 19.25 | 51.56 ± 43.24 b | 49.64 ± 32.69 c |

| GGT (IU/L) | 31.20 ± 34.37 | 58.24 ± 63.33 b | 81.72 ± 82.08 c |

| AKP (IU/L) | 71.68 ± 20.09 | 81.68 ± 23.52 b | 82.76 ± 20.72 c |

| TB (µmol/L) | 10.92 ± 4.46 | 10.84 ± 2.91 | 9.80 ± 2.74 |

| ALB (g/L) | 44.66 ± 3.22 | 45.29 ± 4.81 | 43.94 ± 2.58 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 192.88 ± 68.12 | 138.16 ± 55.33 b | 120.92 ± 41.58 c |

Abbreviations: HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBsAb, hepatitis B surface antibody; HBe-Ab, hepatitis B e antibody; HBcAb, hepatitis B core antibody; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, glutamyl transpeptidase; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; TB, total bilirubin; ALB, albumin; PLT, platelet.

a Values are expressed as means ± SD.

b 12th week vs. pretreatment P-value < 0.05.

c 24th week vs. pre-treatment P-value < 0.05.

As required by the study, we drew 5 ml of fasting blood from the patients and immediately processed it according to standard operating procedures. Sera from 25 samples that met the inclusion criteria were categorized based on the duration of treatment: The first group (F-P, n = 25) commenced prior to interferon administration, the second group (S-P, n = 25) underwent therapy for up to 12 weeks, and the third group (T-P, n = 25) received treatment for up to 24 weeks. The samples were organized to facilitate the integration of sera with corresponding clinical data. The comprehensive technical procedures employed in this project are detailed in Appendix 1 in Supplementary file.

3.2. Sample Preparation

As previously mentioned, to mitigate the impact of individual patient variability, serum samples from each subject (n = 5) were pooled into a single group, thereby ensuring a homogeneous cohort (28, 31). Following the instructions provided by the manufacturer, the combined sera were fractionated into high and low abundance proteins utilizing multiple affinity removal system columns from Agilent technologies, based in Santa Clara, CA, USA. Subsequently, the protein components were desalted and concentrated using 5-kDa ultrafiltration tubes (Sartorius, Germany). Proteins were precipitated with SDT lysis buffer at 95℃ for 15 minutes and subsequently subjected to centrifugation at 14,000 g for 20 minutes. A quantity of 4 μg of trypsin (Promega, USA) was incorporated into the digestion buffer, followed by desalting and vacuum drying. Finally, protein concentration was quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, USA), and the resulting clarified lysate was stored at -80℃ until further analysis.

3.3. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The resulting peptide fractions were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis using a trapped-ion-mobility spectrometry TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) operating in positive ion mode, in conjunction with the Evosep One system for liquid chromatography (Evosep Biosystems, Odense, Denmark) under a DIA mode for high-energy collision dissociation (HCD) fragmentation. Initially, tryptic peptides were dissolved in mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and directly injected into a reverse-phase trap column (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Separation was achieved on an EASY-Spray C18-reversed phase analytical column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a linear gradient of mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid and 84% acetonitrile) over 120 minutes at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. In summary, following nanoflow high-performance liquid chromatography, the most abundant precursor ions were selected from the survey scan within the range of 300 - 1,800 m/z, with a resolution of 60,000 at m/z 200. The automatic gain control target was set to 1e6, with a dynamic exclusion duration of 30 ms and a maximum ion injection time of 50 ms. In MS/MS acquisition, the top 20 precursor ions were fragmented using HCD spectra at 30 eV, with a resolution of 15,000 at m/z 200, an isolation width of 1.5 m/z, and an underfill ratio of 0.1%.

3.4. Proteomics Bioinformation Analysis

We utilized the UniProt-human database for DIA quantitative proteomics analyses and employed the Spectronaut Pulsar X TM 12.0.20491.4 software (Biognosys, version 14.4.200727.47784) for the processing of data-dependent acquisition (DDA) data and the generation of spectral libraries. The data presented herein are derived from protein identifications with a false discovery rate (FDR) of ≤ 1%, thereby ensuring a confidence level of 99% (Appendix 2 in Supplementary file). The deconvolution of the DIA data and DDA spectral libraries facilitated the acquisition of both qualitative and quantitative insights into peptides and proteins. The significantly differentially expressed proteins were subjected to hierarchical clustering analysis utilizing Cluster 3.0 software, accessible online. The resulting data were subsequently visualized with Java TreeView. A volcano plot was employed to illustrate the differentially expressed proteins, with the x-axis representing the log2-transformed fold change and the y-axis indicating the negative log10 of the P-value derived from a two-tailed t-test. Gene ontology (GO) annotation and pathway enrichment analyses were performed on the differentially expressed proteins using Blast2GO software with default settings, focusing on biological processes (BPs), molecular functions (MFs), and cellular components (CCs). Furthermore, the selected differentially expressed proteins were queried against the Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) database to determine their KEGG orthology identities. The protein pathways were then analyzed using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server.

3.5. Validation of Selected Dysregulated Proteins by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The expression levels of selected proteins in serum samples were confirmed through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as previously documented (28). Initially, the serum samples were thawed, centrifuged, and aliquoted for the analysis of specific dysregulated proteins using an ELISA kit procured from Abcam, Cambridge, UK, following the manufacturer's protocol. Concentrations were automatically determined using an ELISA model ELX 800 from BioTek Inc., Winooski, VT, USA, based on the standard curve and dilution factors. Each sample underwent triplicate analysis, and the coefficient of variation for both inter-assay and intra-assay measurements was maintained below 5%.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were collected from a minimum of three independent replicates and subsequently processed and analyzed using Student’s t-test to compare the two groups, with results expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined at a threshold of P < 0.05. Correlations between variables were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation test. Data plotting and statistical analyses were performed utilizing SPSS software (version 23.0) and GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0), respectively.

4. Results

4.1. Comparison of Clinical Characteristics and Relative Quantification of the Serum Proteome

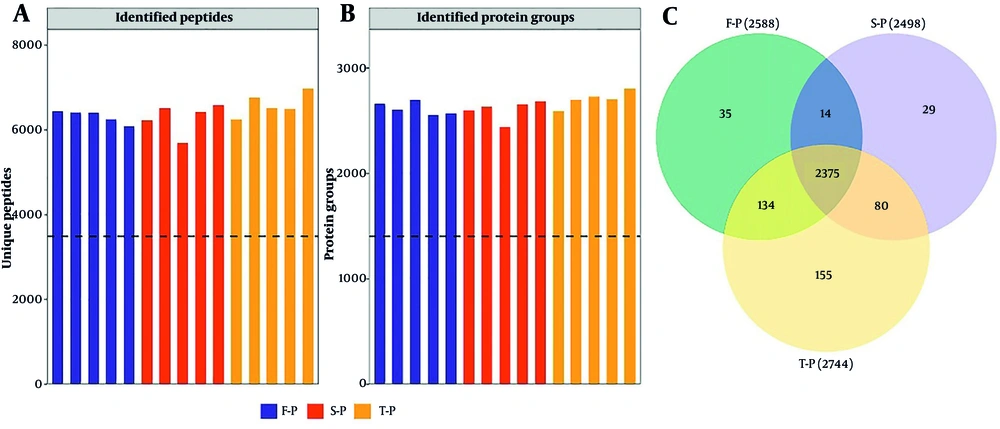

We sorted serum samples from 25 CHB patients showing a rapid treatment response into F-P, S-P, and T-P groups according to how long they were treated, with each group having 25 samples. Upon comparing the clinical characteristics across the three groups, it was determined that there were no statistically significant differences in age and gender among them. However, significant differences were observed between the T-P and S-P groups regarding HBsAg, hepatitis B core antibody (HbcAb), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (AKP), and platelet count (PLT) when compared to the F-P group (Table 1). Concurrently, we conducted a quantitative proteomic analysis using DIA methodology, employing the UniProt human database and Spectronaut software for data processing. This analysis identified a total of 3,174 proteins derived from 8,934 peptides (Figure 1A and B, Appendices 4 and 5 in Supplementary File). The three identified protein groups consisted of 2,534, 2,564, and 2,584 duplicate proteins, respectively (Figure 1C). Of the quantified proteins, 2,503 were consistently observed across all three assays, representing 78.86% of the total.

4.2. Functional Annotation of Differentially Expressed Proteins

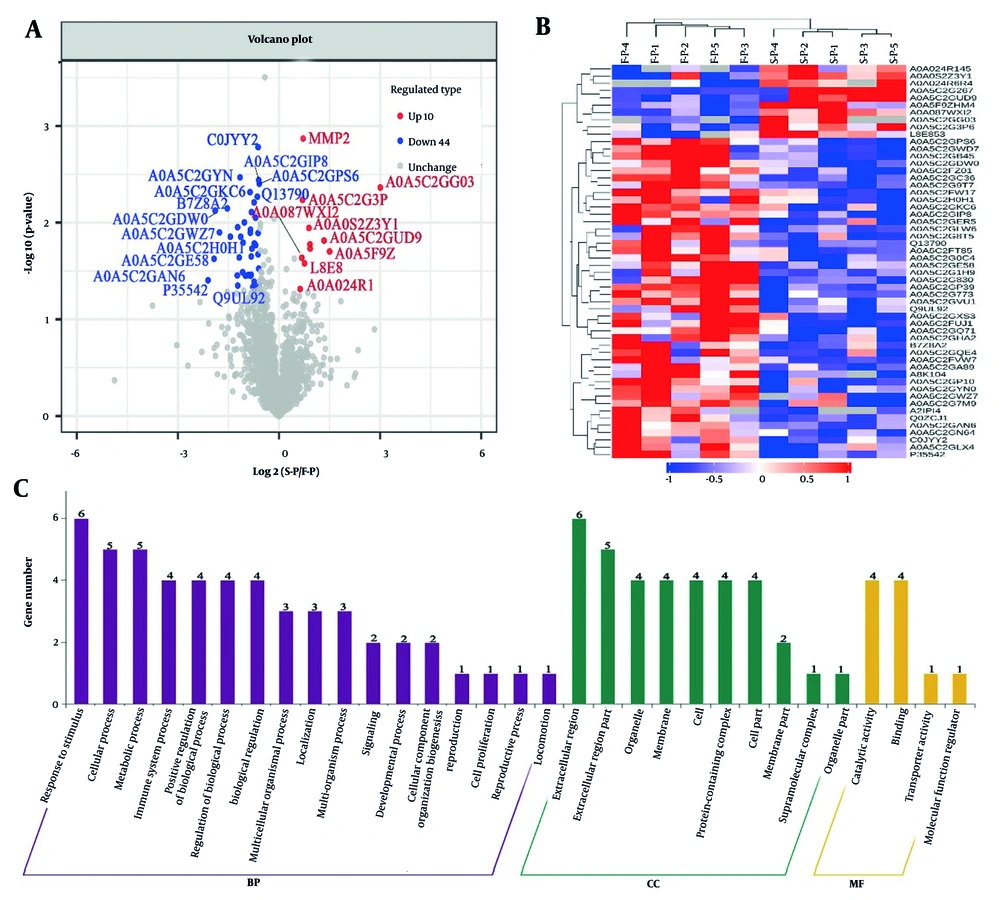

This study evaluated the differential expression of proteins between groups by identifying proteins that were either up-regulated or down-regulated, based on a criterion of greater than a 1.5-fold increase or less than a 1.5-fold decrease, with a significance threshold of P < 0.05. Hierarchical cluster analysis identified 54 proteins (S-P and F-P) that showed differential expression in the serum protein levels of patients (Figure 2A, Appendix 4 in Supplementary File). Visualization of these proteins using a heat map indicated that 44 proteins were up-regulated, whereas 10 proteins were down-regulated in the comparison of protein levels between S-P and F-P blood samples. These two groups of proteins were further distinguished as separate clusters (Figure 2B, Appendix 3 in Supplementary File). The proteins that were typically differentially expressed are listed in Table 2. The GO enrichment analysis was performed to investigate the BPs associated with these 54 proteins, revealing several categories of BPs. Notably, response to stimuli (n = 6), cellular processes (n = 5), and metabolic processes (n = 5) were the most significantly enriched categories (Figure 2C, Appendix 6 in Supplementary File). The analyses indicate distinct molecular mechanisms and functions between S-P and F-P in patients with CHB.

Bioinformatics analysis of serum differential proteins in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients treated for 12 weeks (S-P) vs. pretreatment (F-P): A, volcano plot of the change in abundance of differential proteins in the two groups, with a total of 54 differential proteins identified; B, hierarchical clustering analysis of 54 dysregulated proteins; C, gene ontology (GO) analysis of 54 dysregulated proteins.

| Protein Ac-cession | Protein Description | Gene Name | Fold Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-P/F-P | T-P/F-P | T-P/S-P | |||

| L8E853 | Von Willebrand factor | VWF | 1.6 | 1.34 | 0.84 |

| C0JYY2 | Apolipoprotein B [Including Ag(X) antigen] | APOB | 0.67 | 0.77 | 1.15 |

| A0A024R145 | Fructose-bisphosphate al-dolase | ALDOB | 1.54 | 1.52 | 0.98 |

| A0A0S2Z3Y1 | Lectin galactoside-binding sol-uble 3 binding protein isoform 1 (fragment) | LGALS3BP | 1.89 | 2.25 | 1.19 |

| P35542 | SAA4 | SAA4 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.90 |

| A0A0S2Z4I5 | Complement factor properdin isoform 1 (fragment) | CFP | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.81 |

| A0A087WXI2 | IgGFc-binding protein | FCGBP | 1.62 | 1.61 | 0.99 |

| O75882 | Attractin | ATRN | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.91 |

| Q13790 | Apolipoprotein F | APOF | 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.76 |

| A0A024R6R4 | MMP2 | MMP2 | 2.83 | 2.88 | 1.02 |

| A0A0S2Z3Y1 | Lectin galactoside-binding sol-uble 3 binding protein isoform 1 (fragment) | LGALS3BP | 1.89 | 2.25 | 1.19 |

Abbreviations: SAA4, serum amyloid A-4 protein; MMP2, matrix metallopeptidase 2.

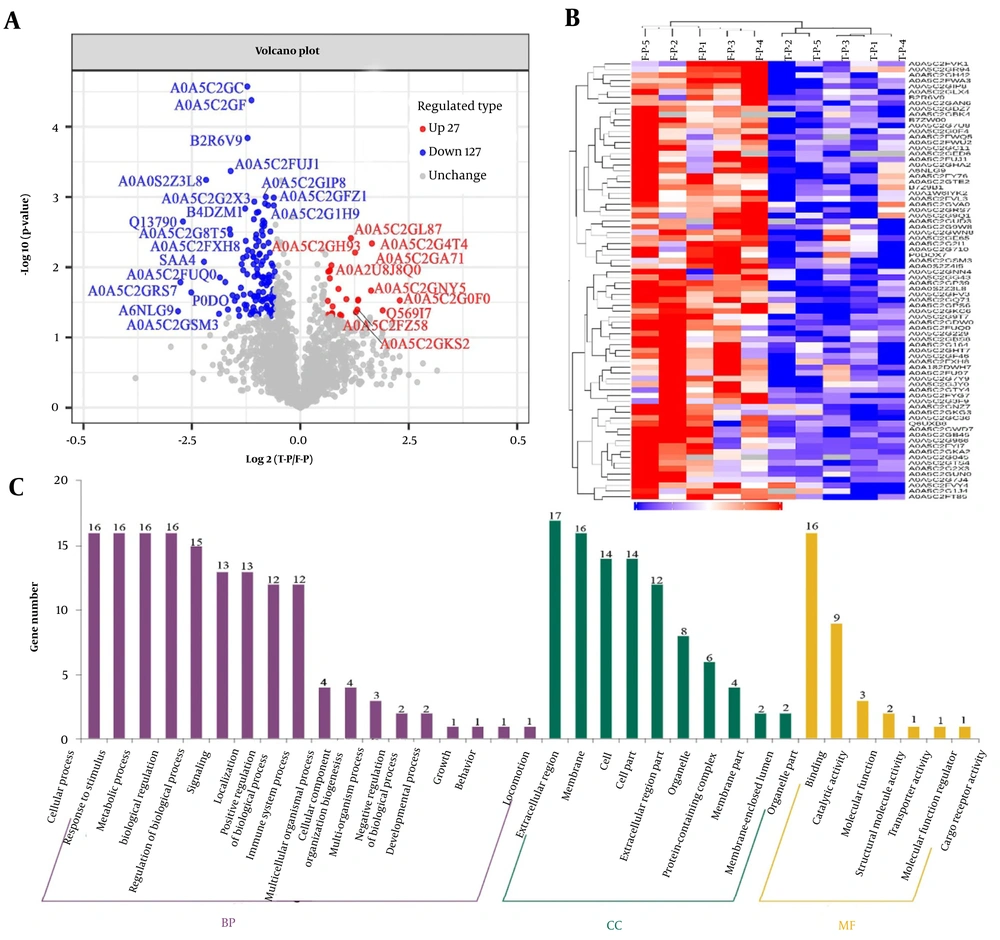

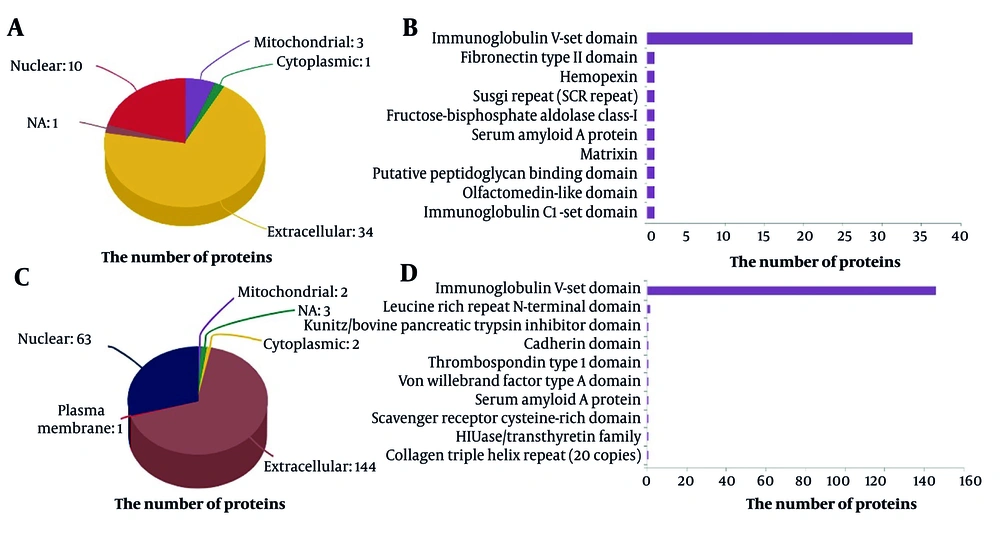

Similarly, variations in serum protein levels between the T-P and F-P groups were assessed using consistent methodologies (Figure 3). Figure 3A illustrates that 154 serum proteins exhibited differential expression in T-P compared to F-P. A heat map of these protein ratios revealed that 27 proteins were upregulated and 127 were downregulated between the T-P and pretreatment groups. Furthermore, these proteins formed distinct clusters (Figure 3B). The deregulated proteins identified in the GO enrichment analysis were associated with biological regulation (n = 16), metabolic processes (n = 16), and cellular processes (n = 16; Figure 3C, Appendix 7 in Supplementary File). Subsequent analysis of the subcellular localization of these differentially expressed proteins revealed predominant expression outside the cell and within the nucleus (Figure 4A and C). A comprehensive analysis of the subcellular localization of differential proteins indicated a strong association between proteins in the S-P and T-P groups and immunoprotein structural domains (Figure 4B and D). As a result, we observed notable differences in the BPs and MFs of patients with CHB undergoing combination therapy.

Bioinformatics analysis of serum differential proteins in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients treated for 24 weeks (T-P) vs. pretreatment (F-P): A, volcano plot of the change in abundance of differential proteins in the two groups, with a total of 154 differential proteins identified; B, hierarchical clustering analysis of 154 dysregulated proteins; C, gene ontology (GO) analysis of 154 dysregulated proteins.

4.3. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathway Enrichment Analysis

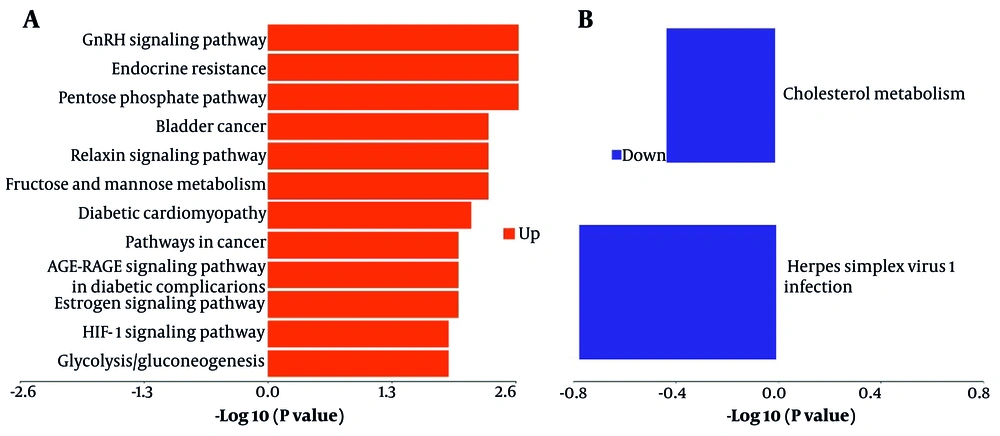

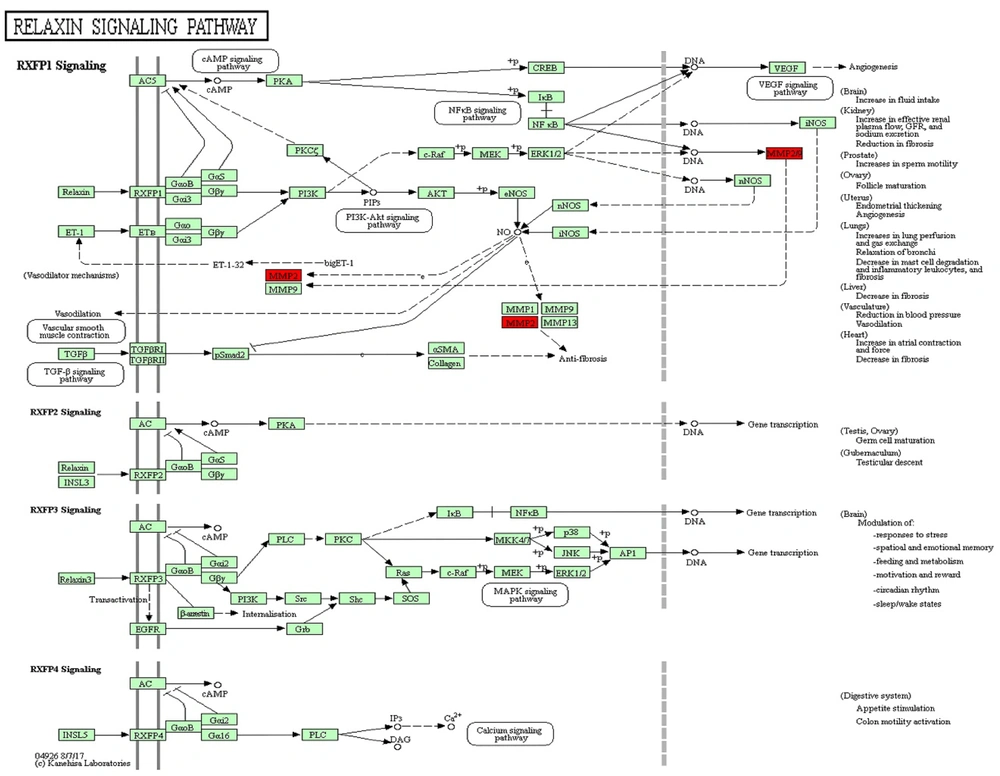

A KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was conducted on proteins exhibiting differential expression to elucidate the characteristics of metabolic pathway enrichment and to identify regulatory pathways associated with the observed changes before and after combination therapy. The results indicated that proteins with altered expression during combination therapy exhibited significant modifications in signaling pathways closely related to therapeutic efficacy (Figure 5). Through pathway analysis of differentially expressed proteins, we determined that upregulated protein expression was primarily associated with the pentose phosphate pathway, relaxin signaling pathway, GnRH signaling pathway, endocrine resistance, and HIF-1 signaling pathway (Figure 5A). The downregulation of protein expression was predominantly associated with cholesterol metabolism and the infection pathway of herpes simplex virus 1 (Figure 5B). Although the signaling pathways of the expressed proteins differed between the T-P and S-P groups, they shared certain pathways, including cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions and leukocyte transendothelial migration. These findings suggest the involvement of multiple distinct pathways in modulating the host's response to suppress HBV replication and protein expression during combination therapy in patients with CHB.

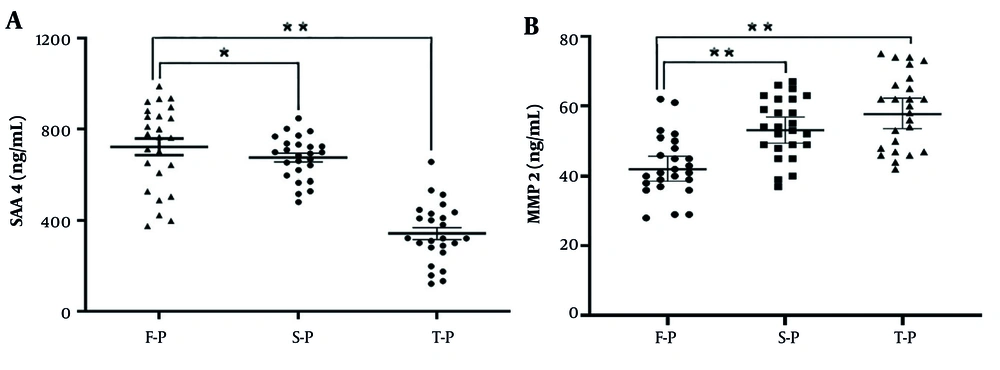

4.4. Key Differential Protein Analysis

Based on the results of hierarchical clustering analysis (Figures 2C and 3C) and the specific protein annotations of significant pathway maps (Figure 6), the proteins matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP2) and serum amyloid A-4 protein (SAA4) were identified as key differentially expressed proteins before and after combination therapy in patients with CHB. These findings were further validated through ELISA in comparison to serum samples from patients in the F-P group, confirming the identification of SAA4 and MMP2 proteins. The expression of the SAA4 protein was observed to be downregulated by 1.36-fold and 1.83-fold in the S-P and T-P groups, respectively (n = 25 patients, P < 0.01) (Figure 7A). In contrast, the expression of the MMP2 protein was significantly upregulated by 2.06-fold and 2.54-fold in serum samples from the S-P and T-P groups, respectively, compared to those from F-P patients (n = 25 patients, P < 0.01) (Figure 7B). These observations are consistent with the findings from DIA-based quantitative proteomics analyses, as detailed in Appendix 5 in Supplementary File. Consequently, these proteins have the potential to serve as novel biomarkers for assessing the efficacy of combination therapy, although further research is required to elucidate their molecular mechanisms.

Validation of the selected differentially expressed proteins of A, serum amyloid A-4 protein (SAA4); and B, proteins matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP2) in the serum samples from chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients who have chosen combination therapy by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the validation cohort; data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 25, * P < 0.05, and ** P < 0.01).

5. Discussion

Owing to significant global advancements towards the elimination of HBV, there has been a decline in the worldwide prevalence of chronic HBV infection over time; however, CHB and its associated complications, such as cirrhosis and HCC, continue to pose a substantial public health threat on a global scale (3, 32, 33). The primary aim of contemporary treatment for patients with CHB is to achieve a clinical cure, characterized by the elimination of HBsAg, with or without seroconversion to HBsAb, and the reduction of HBV DNA levels to below detectable thresholds (33). In patients receiving combination therapy with TDF and PEG-IFN-α, an early reduction in HBsAg levels exceeding 1 log10 IU/mL during treatment indicates a favorable condition for achieving a functional cure (10).

A recent study has shown that long-term NAs treatment, when combined with the presence of inactive HBsAg carriers with low HBsAg levels, has the capacity to "reactivate" immune cells characterized by impaired functionality; reduced levels of viral antigens in the blood and liver have been demonstrated to restore some HBV-related immune functions, resulting in the formation of a "dominant population" that contributes to functional cure (34). Another study indicated that changes in serum cytokines during sequential therapy are associated with the likelihood of achieving a functional cure. Specifically, an increase in Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines in helper T cells (Th) during therapy is linked to a positive virological response (12). Additionally, numerous studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between the efficacy of combination therapy and the duration of treatment (24-26). However, the specific biochemical mechanisms responsible for the rapid decline in HBsAg following early combination therapy remain inadequately understood.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to characterize serum proteomics following combination therapy in CHB patients. By identifying potential biomarkers associated with treatment efficacy, these findings provide valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the treatment-induced reduction in HBsAg. These results hold significant potential for advancing our understanding of CHB treatment.

In the present study, using DIA-based quantitative proteomics, we assessed the serum protein levels in CHB patients whose HBsAg levels dropped by more than 1 log10 IU/mL following 12 and 24 weeks of combination therapy and identified differences in protein levels. The presence of a large number of duplicated proteins in the blood samples of the three groups served to confirm the consistency of the experimental procedure and the reliability of the study results. Molecular differences in the expression of dysregulated proteins in S-P and T-P were identified through functional analysis and signaling pathway studies, using F-P as a control. Although all the proteins mentioned above were involved to varying degrees during the treatment, the pivotal discovery was that chemotactic activity was the sole MF shared between both control groups (S-P vs. F-P and T-P vs. F-P). The findings suggest that the chemoattractant activity in CHB patients undergoing combination therapy may be associated with the rapid decline in HBsAg levels.

Chemokines, crucial for regulating immune cell movement and localization, play a significant role in maintaining immune system balance and facilitating cell interactions, which are essential for infection response, inflammation, and homeostasis (35). The HBV infection increases chemokine production, leading to an accumulation of inflammatory cells like T lymphocytes and neutrophils, which aids in viral clearance and enhances the immune response. Chemokines also promote cell growth and immune response to HBV infection. Additionally, Luo et al. demonstrated that the immune cytokine C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13, linked to HBV infection, can predict the response to PEG-IFN-α treatment in CHB patients, supporting our hypothesis (36).

The SAA4 was identified as a dysregulated protein with chemotactic MF in this study, exhibiting sustained downregulation following combination therapy. As a constituent of the serum amyloid A (SAA) family, SAA4 typically exhibits stable expression levels during episodes of acute inflammation. Nonetheless, within the framework of chronic inflammation, it may contribute to metabolic disorders linked to persistent inflammatory conditions by influencing lipid metabolism (37, 38). Through the mediation of the receptor for advanced glycation end products and nuclear factor κB pathways, SAA4 stimulates the production of IL-6, a cytokine that facilitates monocyte colony formation. Moreover, SAA4 induces the expression of protein kinase R via the activation of signaling pathways, including toll-like receptors and mitogen-activated protein kinase (39). Notably, another study revealed that patients with advanced liver fibrosis had lower levels of SAA4 expression (40). There is a scarcity of studies exploring the connection between SAA4 and chronic HBV infection. Our research proposes that serum SAA4 might be an effective indicator for assessing combination therapy outcomes in CHB cases.

Furthermore, several proteins associated with these functions, including MMP2, exhibited dysregulation as identified through KEGG relaxin signaling pathway analysis. During the S-P phase, there was a significant upregulation of MMP2 expression, whereas during the T-P phase, MMP2 levels showed a slight increase from baseline. Myofibroblasts are responsible for producing matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), such as MMP2, which are crucial for the degradation of various extracellular matrix proteins and facilitate processes like apoptosis, tissue repair, and immune responses (41). The MMP family, encompassing MMP2, contributes to physiological processes by enzymatically degrading gelatin and types IV and V collagen.

In addition, existing research has demonstrated the involvement of MMP2 in immune responses and its association with immune cells. For example, dendritic cells regulated by MMP2 facilitate the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into an inflammatory Th2 phenotype by cleaving type I interferon receptors in an MMP2-dependent manner, leading to decreased IL-12 production (42). Contrastingly, Yang et al. investigated the roles of MMP2/9 in the elimination of HBV, revealing that elevated MMP2/9 levels induce the release of membrane-bound semaphorin 4D (CD100) and increase soluble CD100 levels on T cells in patients with CHB. Consequently, intrahepatic anti-HBV CD8+ T-cell responses were enhanced, resulting in accelerated HBV clearance (43).

The findings of this study suggest that the levels of SAA4 and MMP2 following combination therapy in patients with CHB may modulate the host T-cell immune system, thereby contributing to the recovery of CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells. Overall, we analyzed the alterations in serum protein levels before and after combination therapy and proposed SAA4 and MMP2 as potential biomarkers for assessing the efficacy of the treatment. However, the mechanism of how SAA4 and MMP2 specifically drive immune regulation during the disease process remains unclear.

In conclusion, an analysis was conducted of serum protein profiles in patients undergoing combination therapy at baseline, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks. This analysis led to the identification of two potential biomarkers and possible therapeutic targets for diseases associated with HBV infection. However, the study is subject to certain limitations, including a relatively small sample size and a limited duration for assessing patient outcomes. Furthermore, the DIA-based MS analysis was performed on a limited number of serum samples, providing only a broad overview of differential protein expression. It is imperative to investigate the functions of crucial dysregulated proteins through large-sample-size studies.

5.1. Conclusions

We utilized DIA-based MS analyses to examine the differences in serum proteomic profiles across the S-P, T-P, and F-P groups. After treatment, 208 proteins showed significant changes, and we identified potential molecular mechanisms by which MMP2 and SAA4 could play a role in reducing HBsAg. To validate these results, we examined the differences in MMP2 and SAA4 expression levels in the groups using ELISA. While quantitative proteomic analyses remain mostly descriptive, identifying key proteins offers valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms of combination therapy.