1. Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major cause of acute and chronic liver disease worldwide, with an estimated 254 million people living with chronic HBV infection in 2022, resulting in approximately 1.1 million deaths annually due to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (1). Coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an important clinical concern because it alters the natural history of HBV infection. Approximately 1% of individuals with chronic HBV infection are coinfected with HIV, increasing the risk of chronicity, higher viral loads, faster progression to cirrhosis, and poorer outcomes (2, 3).

Acute HBV infection is usually self-limiting; however, in rare cases, it can present with a cholestatic course characterized by prolonged jaundice, pruritus, and marked hyperbilirubinemia (4). The presence of HIV coinfection in such cases complicates management by impairing immune control and influencing treatment decisions (5, 6). Early recognition of HIV in HBV patients is critical, as antiretroviral therapy (ART) not only suppresses HIV but also targets HBV, particularly with tenofovir-based regimens (7).

Recent studies identified novel mechanisms of HBV-related hepatocellular injury, including dysregulated autophagy and mitochondrial pathways causing viral persistence and cholestatic damage (8). Recent evidence further demonstrates that HBV-induced autophagy dysregulation may impair bile acid transport and exacerbate cholestatic injury, contributing to prolonged hyperbilirubinemia in severe presentations. The HBV reactivation during immunosuppressive or targeted therapies has also become a major clinical issue (9). In the context of HIV coinfection, immune dysregulation may heighten susceptibility to HBV reactivation, necessitating careful virological monitoring. Furthermore, machine-learning-aided antiviral optimization offers new insight into personalized HBV management (10). Such individualized therapeutic strategies may be particularly valuable in complex HBV-HIV coinfection scenarios, where treatment selection must balance efficacy with hepatotoxicity risk.

Besides viral causes, other differential diagnoses must be considered in prolonged cholestasis. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced cholangitis is an important cause that can mimic viral hepatitis, underscoring careful diagnostic evaluation (11, 12). Additionally, recent reports describing immune-mediated hepatocellular injury patterns highlight the relevance of host immune dysregulation in cases of prolonged cholestasis.

Here we present an unusual prolonged cholestatic acute HBV case revealing underlying HIV infection, emphasizing early HIV testing and management challenges of ART in severe cholestasis.

2. Case Presentation

A 39-year-old man engaged in the textile business was admitted with a two-week history of anorexia, fatigue, nausea, and abdominal bloating. During the preceding week, he noted dark-colored urine, yellowing of the eyes, and night sweats severe enough to require changing clothes. He denied vomiting, diarrhea, alcohol use, or previous liver disease but reported recent unprotected sexual contact. The patient reported no recent use of hepatotoxic medications, over-the-counter supplements, or herbal products.

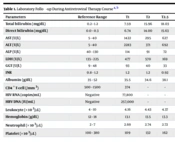

On admission, the patient was alert and oriented, with marked jaundice of the skin and sclerae. Abdominal examination was normal, with no hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or signs of hepatic encephalopathy. Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated total bilirubin (7.6 mg/dL), ALT (2283 U/L), and AST (1422 U/L, Table 1). Serology was positive for HBsAg, anti-HBc IgM, and HBeAg, confirming acute HBV. Abdominal computed tomography showed hepatosplenomegaly and reactive gallbladder wall thickening consistent with acute hepatitis. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography excluded biliary obstruction or space-occupying lesions.

| Parameters | Reference Range | T1 | T2 | T2.5 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 - 1.2 | 7.59 | 15.96 | 18.03 | 29.38 | 25.84 | 22.00 | 21.96 | 13.80 | 7.09 | 1.39 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.0 - 0.3 | 6.74 | 14.00 | 15.63 | 25.10 | 24.20 | 19.62 | 20.74 | 12.89 | 5.56 | 1.02 |

| AST (U/L) | 5 - 40 | 1422 | 295 | 627 | 711 | 892 | 158 | 102 | 81 | 169 | 21 |

| ALT (U/L) | 5 - 40 | 2283 | 371 | 692 | 814 | 511 | 514 | 113 | 695 | 198 | 18 |

| ALP (U/L) | 40 - 130 | 114 | 91 | 72 | 83 | 89 | 97 | 99 | 70 | 98 | 47 |

| LDH (U/L) | 135 - 225 | 477 | 570 | 169 | 144 | 170 | 137 | 118 | 113 | 157 | 152 |

| GGT (U/L) | 9 - 48 | 93 | 40 | 33 | 27 | 20 | 32 | 39 | 31 | 66 | 25 |

| INR | 0.8 - 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.92 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.17 | 1.02 | 1.18 | 0.97 | 0.92 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 35 - 52 | 35.5 | 34.6 | 38.1 | 35.8 | 35.6 | 34.8 | 39.4 | 29.6 | 40.1 | 44.6 |

| CD4+ T-cell (/mm3) | 500 - 1500 | 374 | - | - | - | 376 | - | - | - | - | 381 |

| HIV RNA (copies/mL) | Negative | 77,800 | - | - | - | 126 | - | - | - | - | 54.2 |

| HBV DNA (IU/mL) | Negative | 257,000 | - | - | - | < 10 | - | - | - | - | < 10 |

| Leukocyte (× 103/µL) | 4 - 10 | 4.16 | 4.43 | 4.37 | 4.92 | 5.65 | 4.16 | 1.53 | 1.03 | 4.36 | 4.42 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12 - 18 | 13.1 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 13.7 | 13.0 | 13.1 | 13.2 | 10.3 | 14.3 | 13.8 |

| Neutrophil (× 103/µL) | 2 - 7 | 2.69 | 2.74 | 2.72 | 3.56 | 4.22 | 2.69 | 0.86 | 0.13 | 2.77 | 2.76 |

| Platelet (× 103/µL) | 100 - 380 | 109 | 132 | 162 | 128 | 147 | 109 | 115 | 100 | 131 | 116 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

a T1: First admission; T2: Antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation; T2.5: Early response phase; T3: Pre-discontinuation of ART; T4: ART reinitiation; T5: Discharge after first admission; T6 - T8: Second hospitalization and follow-up; T9: Third month of ART.

b Reference ranges are shown in the second column.

Further screening identified HIV RNA 77,800 copies/mL and a CD4+ T-cell count of 374/mm3, establishing concurrent HIV infection. Genotypic resistance testing and HLA-B*5701 screening were performed before therapy initiation. Given that the clinical and laboratory findings were consistent with acute viral HBV, additional autoimmune and hereditary tests (ANA, AMA, SMA, ceruloplasmin, and α-1-antitrypsin) were not performed. However, serum ferritin and transferrin saturation were assessed to exclude metabolic iron overload, showing marked hyperferritinemia (5375 ng/mL) and high transferrin saturation (99%) at presentation, both normalizing during recovery (ferritin 532 ng/mL, transferrin saturation 25%). These findings supported an acute-phase response rather than hereditary hemochromatosis (Tables 2 and 3). Given the clinical trajectory and recovery pattern, autoimmune and hereditary metabolic liver diseases were considered but were not supported by the serological evolution; therefore, further broad autoimmune screening was not warranted.

| Parameters | Result | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-HBs | Negative | Positive |

| Anti-HBc IgM | Positive | Positive |

| HBsAg | Positive (1967 IU/mL) | Positive |

| HBeAg | Positive (170 IU/mL) | Positive |

| Anti-HBe | Negative (6.75 IU/mL) | Negative |

| HBV DNA | 257,000 IU/mL | Negative |

| Anti-HCV | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-HAV IgM | Negative (0.10) | Negative |

| Anti-HAV IgG | Negative (0.13) | Positive |

| Anti-HIV | Positive | Positive |

| HIV RNA | 77,800 copies/mL | Negative |

| Anti-HDV | Negative | Negative |

| CD4+ T-cell (%) | 35% | - |

| IgG | 21.52 g/L | 7 - 16 g/L |

| IgM | 0.95 g/L | 0.4 - 2.3 g/L |

| IgA | 3.57 g/L | 0.7 - 4 g/L |

| PCR respiratory panel a | Negative | Negative |

Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a PCR respiratory panel includes SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A, influenza B, influenza A H1, influenza A H3, pandemic H1N1, coronavirus 229E, coronavirus OC43, coronavirus NL63, coronavirus HKU1, parainfluenza 1 - 4, RSV A/B, Rhinovirus, Enterovirus, Metapneumovirus, Adenovirus, Bocavirus, Parechovirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Haemophilus influenzae (including type B), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Bordetella pertussis.

| Parameters | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| EBV VCA IgM | 0.03 | Non-reactive |

| EBV VCA IgG | 40.84 | Reactive |

| CMV IgG | 243.0 | Reactive |

| CMV IgM | 0.18 | Non-reactive |

| Anti-HAV IgG | 0.12 | Negative |

| Anti-HAV IgM | 0.10 | Negative |

| Anti-HBc IgG | 3.77 | Positive |

| Anti-HBs | 0.00 | Negative |

| Anti-rubella IgG | 53.5 | Reactive |

| Anti-rubella IgM | 0.05 | Non-reactive |

| Anti-toxoplasma IgM | 0.08 | Non-reactive |

| Anti HBc IgM | 28.15 | Positive |

| Anti-toxoplasma IgG | 0.2 | Non-reactive |

| Varicella zoster virus IgG | 5.62 | Positive |

| VDRL | Negative | Non-reactive |

| TPHA | Negative | Non-reactive |

Abbreviations: VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test; TPHA, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay.

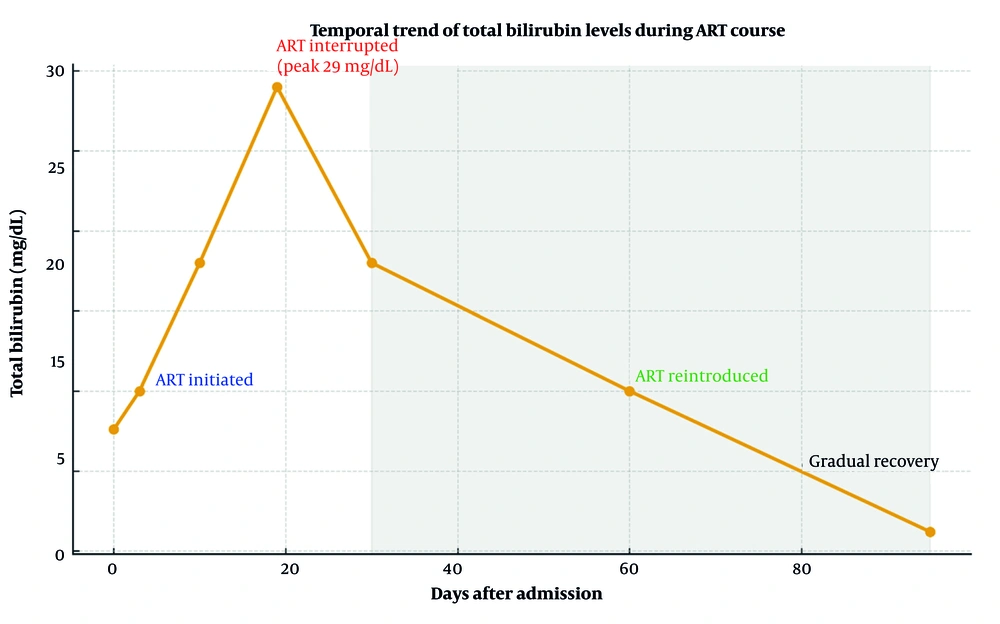

The ART with bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide was started according to current guidelines. On day 19, total bilirubin rose sharply to 29 mg/dL, prompting temporary discontinuation of ART due to suspected drug-induced hepatotoxicity contributing to cholestasis. Ursodeoxycholic acid, which had been prescribed for supportive management, was also stopped at that time. Bilirubin levels gradually declined, and ART was safely reintroduced after clinical improvement without recurrence of hepatotoxicity.

The patient experienced persistent hyperbilirubinemia lasting 95 days in total. During follow-up, no signs of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) were observed. At the third month of ART, HIV RNA levels decreased markedly, while CD4+ counts improved to 381/mm3. Supportive therapy, including lactulose and a short course of intravenous N-acetylcysteine, was administered. The patient remained clinically stable, with progressive resolution of jaundice and normalization of liver function tests (Table 1).

Figure 1 summarizes the temporal changes in total bilirubin levels and the timeline of ART initiation, discontinuation, and re-initiation, illustrating the correlation between biochemical improvement and antiviral control.

3. Discussion

The HBV and HIV share similar transmission routes and are frequently found together, with HIV-induced immunosuppression contributing to more severe outcomes in HBV infection (2, 3). Coinfected patients tend to have higher HBV DNA levels, an increased risk of chronicity, and faster progression to cirrhosis compared with HBV monoinfection. Acute HBV infection complicated by the simultaneous diagnosis of HIV infection is rare, with only a limited number of such cases reported in the literature (5, 13). This underscores the importance of routine HIV screening in patients presenting with atypical or severe HBV manifestations, as early diagnosis can guide appropriate management and prevent further hepatic injury. Recent clinical experience also indicates that HIV-HBV coinfection may accelerate liver disease progression, supporting early initiation of tenofovir-based ART in accordance with current international treatment recommendations.

Early initiation of ART is critical for the management of HIV and HBV coinfection, as tenofovir-based regimens provide dual antiviral activity (6). In this patient, bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide was started promptly, consistent with current recommendations. However, the marked rise in bilirubin levels following ART initiation raised concerns for drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Bictegravir- and emtricitabine-containing regimens have been associated with mild, transient elevations in bilirubin in 4 - 12% of patients, usually not requiring discontinuation (14). Severe unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia requiring modification has rarely been reported (15). In our case, the temporal pattern of bilirubin elevation and subsequent improvement after temporary treatment interruption was more consistent with cholestasis related to acute HBV rather than primary ART-induced hepatotoxicity.

Another important differential consideration was IRIS, which has been reported in HIV-infected patients initiating ART (7). However, in this case, the absence of fever, lymphadenopathy, or opportunistic infection, combined with stable CD4+ counts and rapid HIV RNA suppression, argued against IRIS. The prolonged hyperbilirubinemia was more consistent with the cholestatic variant of acute HBV, a rare but recognized clinical presentation (4). Recent mechanistic studies indicate that HBV can dysregulate autophagy-mediated bile acid transport, contributing to cholestatic liver injury and sustained hyperbilirubinemia in severe acute infection (8)

Additionally, HBV reactivation has increasingly been reported in immunosuppressed or co-infected states, highlighting the importance of careful virological monitoring in HBV-HIV coinfection (9). Moreover, artificial intelligence and machine-learning-assisted antiviral treatment strategies have shown promise in optimizing individualized therapeutic decisions, particularly in patients with overlapping viral and hepatic disease dynamics (10).

The HBV is also known to trigger extrahepatic immune-mediated manifestations, including HBV-associated glomerulonephritis, which reflects the systemic immunopathogenic potential of the virus beyond the liver (16). Such phenomena reinforce the need for comprehensive clinical assessment in patients presenting with severe hepatic involvement.

Supportive treatments including ursodeoxycholic acid, lactulose, and short-course intravenous N-acetylcysteine were administered. Ursodeoxycholic acid has been widely used in cholestatic liver disease to enhance bile flow and protect hepatocytes (17), though its benefit in this patient was limited. N-acetylcysteine was given for its antioxidant and hepatoprotective properties, and recent studies suggest it may reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic HBV infection (18). With careful monitoring and supportive therapy, our patient achieved favorable clinical and virological outcomes.

This case highlights the need for structured evaluation of prolonged cholestasis in acute HBV, including early HIV testing, differentiation between viral and drug-related hepatotoxic mechanisms, and careful timing of ART continuation. A multidisciplinary approach and close biochemical follow-up are essential to optimize outcomes in similar scenarios.

3.1. Conclusions

This case demonstrates that prolonged cholestatic HBV may represent the initial clinical presentation of underlying HIV infection. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for HIV coinfection when acute HBV presents with severe or persistent cholestasis. Early HIV testing and timely initiation of tenofovir-based ART are essential to optimize virological and clinical outcomes. Differentiating viral disease activity from potential drug-induced hepatotoxicity is crucial when initiating ART in the setting of cholestatic liver injury. Supportive measures, careful biochemical monitoring, and individualized treatment planning contribute to successful recovery in HBV-HIV coinfected patients.