1. Background

Globally, alcoholic liver disease (ALD) remains the top-ranked major disease burden (1). Alcoholic fatty liver (AFL), alcoholic hepatitis (AH), and alcoholic liver cirrhosis (ALC) are three primary forms of ALD (2). The ALC is an end-stage condition of ALD, and approximately 10 - 20% of patients with ALD develop cirrhosis (3). It has been estimated that in 2019, approximately one-quarter of the cirrhosis-associated deaths were caused by ALC (4). Especially in young and middle-aged ALC adults aged 15 to 49 years old, there are nearly 4.8 million cases and 78,000 mortality deaths (5). The ALC usually has a poor prognosis, and the mortality rate is as high as 75% at five years (6). To date, the most effective therapy to attenuate the clinical course of alcoholic cirrhosis is alcohol abstinence. For decompensated ALC patients, liver transplant should be considered (7). The ALC is a serious disease with elevated morbidity and mortality (6). Therefore, timely and accurate evaluation is important for the treatment and prognosis of ALC.

Multiple scoring systems have been applied to assess the prognosis of ALD. The Child-Pugh (CP) score, conceptualized by Child and Turcotte in 1964, was proposed to evaluate the outcomes of liver cirrhosis patients after surgery for portal hypertension (8). Later, the CP score has been widely used in clinical practice. The CP score contains five variables: Total bilirubin (TBIL), albumin, prothrombin time (PT), encephalopathy, and ascites. However, encephalopathy and ascites are two variables that may be influenced by subjective appreciation (9, 10). The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, originally, has been used to predict survival after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) (11). As a simple and objective score system, the MELD score includes three variables: Creatinine, TBIL, and international normalized ratio (INR), and has been widely used for patients with end-stage cirrhosis (12, 13). Alternatively, the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score has been proposed for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) for assessing liver function, solely based on albumin and bilirubin (14). Later, the ALBI score has commonly been applied to assess the severity of liver cirrhosis (15, 16). Thus, the same score system may have different predictive abilities for different etiologies of cirrhosis. Accordingly, the accuracy of the above-mentioned scores to predict short-term and long-term outcomes in ALC should be further explored.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to compare different scoring systems in predicting short-term and long-term mortality in ALC patients. In this study, we enrolled ALC patients and compared the prognostic accuracy of six score systems: The CP score, MELD score, ALBI score, age-bilirubin-international normalized ratio-creatinine (ABIC) score, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and Maddrey’s discriminant function (MDF) in ALC patients. Our findings help confirm the accuracy of noninvasive scoring systems for ALC patients.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Patients

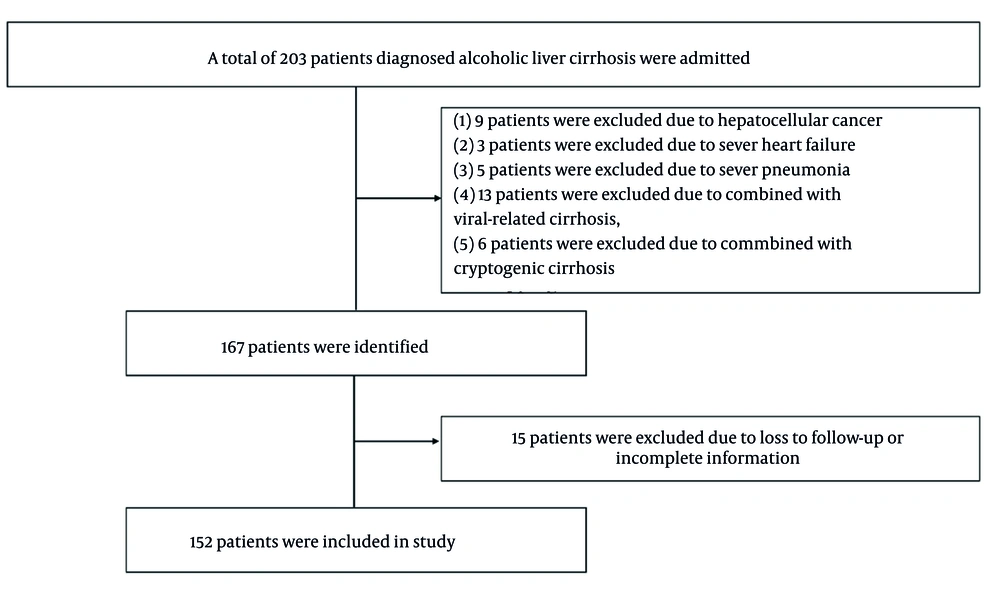

In this retrospective study, data on patients diagnosed with ALC were collected from the First Affiliated Hospital of Jishou University from February 2015 to December 2022. The enrollment of the patients is described in Figure 1. Inclusion criteria were formulated as follows: Patients had been diagnosed with ALC and were over the age of 18 years. The history of long-standing and harmful alcohol consumption, clinical manifestation, serologic measures, and imaging-based indices, such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), were used for the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Age < 18 years, (2) primary or metastatic malignancies, such as hepatocellular cancer, (3) circulatory or respiratory system disease that could affect mortality, such as heart failure or severe pneumonia, and (4) other types of liver cirrhosis, such as viral-related cirrhosis or cryptogenic cirrhosis. Demographics, mortality status, complications, and laboratory parameters were collected. Decompensated cirrhosis is defined by the appearance of hepatic encephalopathy (HE), variceal bleeding, or ascites. In this study, 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month mortality rates were assessed. Predictive values for short-term and long-term mortality were compared between the CP score, MELD score, ALBI score, ABIC score, NLR, and MDF. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Jishou University.

3.2. Calculation of Scores

The CP score was calculated as described by Pugh et al (17).

- The MELD score = 3.78 × ln (TBIL μmol/L) + 11.2 × ln (INR) + 9.57 × ln (creatinine mg/dL) + 6.4 (18).

- The ALBI score = -0.085 × (albumin g/L) + 0.66 × lg(TBIL μmol/L) (14).

- The ABIC score = (age × 0.1) + (TBIL × 0.08) + (INR × 0.8) + (creatinine mg/dL × 0.3) (16).

- The NLR = neutrophil to lymphocyte.

- The MDF = 4.69 × (PT - control PT) + TBIL (mg/dL) (19).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Normality distribution for all variables was checked with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR). Continuous variables were analyzed using the student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. In addition, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was carried out and the area under the curve (AUC) was analyzed to assess the six scoring systems. A Kaplan-Meier analysis was conducted to estimate survival rates. The log-rank test was used to validate the equivalences of the survival curves. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression were performed to assess the effect of independent variables on overall survival. P-value < 0.05 was deemed as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted by SPSS 27.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics

The baseline features of all patients are shown in Table 1. In total, 152 male patients with ALC were enrolled in this study. The age of participants ranged from 29 to 90 years, with a mean age of 57.77 years. One hundred twenty-four (81.6%) patients were diagnosed with decompensated cirrhosis. Complications were as follows: Ascites (n = 117), HE (n = 12), gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 24), and infection (37), including spontaneous peritonitis (n = 13), pulmonary infection (n = 11), urinary tract infection (n = 5), intestinal infection (n = 3), biliary tract infection (n = 3), and skin infection (n = 2). Median CP score, MELD score, ALBI score, ABIC score, NLR, and MDF were 8 (IQR: 3, range: 5 - 15), 6 (IQR: 7, range: -2 to 31), -1.46 (IQR: 0.90, range: -2.92 to -0.28), 7.43 (IQR: 1.65, range: 4.75 - 12.87), 3.43 (IQR: 3.54, range: 0.87 - 39.26), and 18.35 (IQR: 15.72, range: 2.51 - 319.75), respectively (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 57.77 ± 10.78 |

| Laboratory results | |

| White blood count (× 109/L) | 4.97 (3.19, 0.98 - 32.15) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 98.50 (46, 28 - 163) |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) | 84.5 (69, 21 - 297) |

| Neutrophil count (× 109/L) | 3.29 (2.44, 0.34 - 28.72) |

| Lymphocyte count (× 109/L) | 0.92 (0.63, 0.17 - 2.67) |

| AST (U/L) | 47.5 (44, 9 - 1911) |

| ALT (U/L) | 27 (21, 4 - 1258) |

| TBIL (umol/L) | 30.65 (32.7, 4 - 424.3) |

| Total protein (g/L) | 59 (13.2, 30.1 - 84.9) |

| Albumin (g/L) | 28.65 (8, 17.4 - 42.4) |

| Serum creatinine (umol/L) | 78.2 (41.7, 30.6 - 399) |

| γ-GGT (U/L) | 162.5 (306.3, 10 - 2141) |

| ALP (U/L) | 124 (56.8, 32 - 959) |

| PT (s) | 14.8 (3.4, 11.4 - 79.5) |

| INR | 1.30 (0.35, 0.93 - 7.68) |

| Complications | |

| Ascites | 117 (77) |

| HE | 12 (7.9) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 24 (15.8) |

| Infection | 37 (24.3) |

| Spontaneous peritonitis | 13 |

| Pulmonary infection | 11 |

| Urinary tract infection | 5 |

| Biliary tract infection | 3 |

| Skin infection | 2 |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 124 (81.6) |

| Score systems | |

| CP score | 8 (3, 5 - 15) |

| CP class | |

| class A | 21 (13.8) |

| class B | 93 (61.2) |

| class C | 38 (25.0) |

| MELD score | 6 (7, 1-31) |

| ALBI score | -1.47 (0.90, -2.92 to -0.28) |

| ABIC score | 7.43 (1.65, 4.73 to 12.87) |

| NLR | 3.43 (3.73, 0.87 to 39.26) |

| MDF | 18.35 (15.72, 2.51 to 319.75) |

Abbreviations: AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TBIL, total bilirubin; γ-GGT, gamma glutamyl transpeptidase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; CP, Child-Pugh; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; ABIC, age-bilirubin-international normalized ratio-creatinine; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; MDF, Maddrey’s discriminant function.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), No. (%), or median [interquartile range (IQR), range].

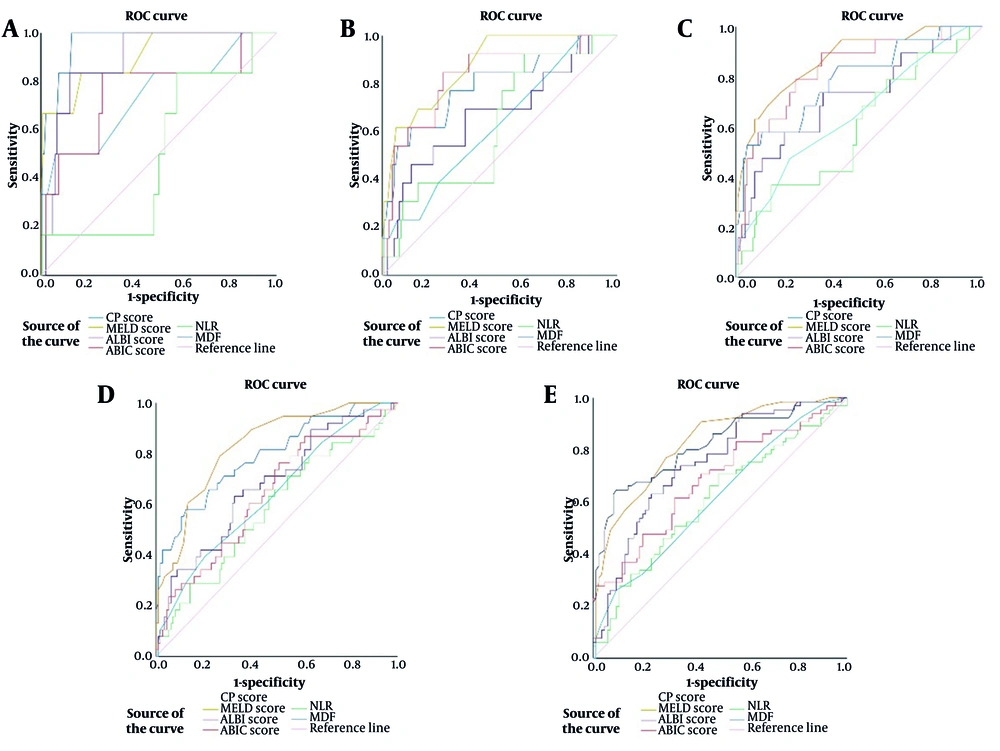

4.2. Comparison of the Prognostic Accuracy of Six Score Systems in 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month Mortality

The ROC curves of all six scoring systems for 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month mortality are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. All scoring systems showed predictive accuracy in predicting 1-month survival (P < 0.05), except for NLR (P = 0.985). Of these, both MELD score (AUROC: 0.902; 95% CI: 0.843 - 0.944, P = 0.001) and MDF (AUROC: 0.963; 95% CI: 0.919 - 0.987, P < 0.001) had excellent accuracy. For 3-month survival, the MELD score (AUROC: 0.873; 95% CI: 0.809 - 0.921, P < 0.001) and ABIC score (AUROC: 0.826; 95% CI: 0.756 - 0.883, P < 0.001) demonstrated high predictive accuracy. For predicting 6-month survival, the MELD score (AUROC: 0.869; 95% CI 0.804 - 0.918, P < 0.001) and ABIC score (AUROC: 0.827; 95% CI: 0.758 - 0.884, P < 0.001) showed good predictive accuracy. Except for NLR (AUROC: 0.582; 95% CI: 0.500 - 0.662, P = 0.131), all the other five score systems had certain predictive values (P < 0.05) in 12-month survival. Of note, the MELD score showed a better prognostic accuracy (AUROC: 0.830; 95% CI: 0.761 - 0.886, P < 0.001). For 24-month survival, all the six score systems had prognostic values (P < 0.05), and the MELD score (AUROC: 0.826; 95% CI: 0.757 - 0.883, P < 0.001) had a higher predictive value.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of Child-Pugh (CP) score, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score, age-bilirubin-international normalized ratio-creatinine (ABIC) score, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and Maddrey’s discriminant function (MDF) for 1-(A), 3-(B), 6-(C), 12-(D), and 24-(E) months

| Survival Months and Scores | Area Under ROC | 95% CI | Cut Off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| CP score | 0.739 | 0.662 - 0.807 | 11 | 50.00 | 93.84 | 0.047 |

| MELD | 0.902 | 0.843 - 0.944 | 10 | 83.33 | 82.88 | 0.001 |

| ALBI | 0.890 | 0.829 - 0.935 | -0.88 | 83.33 | 87.67 | 0.001 |

| ABIC | 0.759 | 0.683 - 0.824 | 8.11 | 83.33 | 73.29 | 0.032 |

| NLR | 0.502 | 0.420 - 0.584 | 3.85 | 16.67 | 52.05 | 0.985 |

| MDF | 0.963 | 0.919 - 0.987 | 32.79 | 100 | 86.99 | < 0.001 |

| 3 | ||||||

| CP score | 0.624 | 0.542 - 0.701 | 11 | 23.08 | 93.53 | 0.140 |

| MELD | 0.873 | 0.809 - 0.921 | 14 | 61.54 | 94.24 | < 0.001 |

| ALBI | 0.666 | 0.586 - 0.741 | -1.25 | 69.23 | 64.75 | 0.048 |

| ABIC | 0.826 | 0.756 - 0.883 | 8.02 | 84.62 | 74.10 | < 00.001 |

| NLR | 0.624 | 0.542 - 0.701 | 2.84 | 92.31 | 39.57 | 0.141 |

| MDF | 0.790 | 0.716 - 0.852 | 32.79 | 61.54 | 87.77 | 0.001 |

| 6 | ||||||

| CP score | 0.649 | 0.568 - 0.725 | 9 | 47.37 | 78.20 | 0.036 |

| MELD | 0.869 | 0.804-0.918 | 9 | 73.68 | 81.95 | < 0.001 |

| ALBI | 0.714 | 0.636 - 0.785 | -1.03 | 57.89 | 80.45 | 0.003 |

| ABIC | 0.827 | 0.758 - 0.884 | 7.69 | 89.47 | 65.41 | < 00.001 |

| NLR | 0.590 | 0.507 - 0.669 | 7.06 | 36.84 | 85.71 | 0.207 |

| MDF | 0.788 | 0.714 - 0.805 | 37.45 | 52.63 | 95.49 | < 0.001 |

| 12 | ||||||

| CP score | 0.638 | 0.556 - 0.714 | 9 | 39.47 | 79.82 | 0.011 |

| MELD | 0.830 | 0.761 - 0.886 | 7 | 78.95 | 73.68 | < 00.001 |

| ALBI | 0.676 | 0.596 - 0.750 | -1.35 | 65.79 | 63.16 | 0.001 |

| ABIC | 0.638 | 0.557 - 0.715 | 6.82 | 86.84 | 38.60 | 0.011 |

| NLR | 0.582 | 0.500 - 0.662 | 3.19 | 65.79 | 50.88 | 0.131 |

| MDF | 0.792 | 0.719 - 0.854 | 28.13 | 57.89 | 87.72 | < 00.001 |

| 24 | ||||||

| CP score | 0.617 | 0.534 - 0.694 | 10 | 26.15 | 90.80 | 0.014 |

| MELD | 0.826 | 0.757 - 0.883 | 4 | 90.77 | 57.47 | < 00.001 |

| ALBI | 0.744 | 0.667 - 0.811 | -1.46 | 72.31 | 67.82 | < 00.001 |

| ABIC | 0.683 | 0.602 - 0.756 | 7.54 | 61.54 | 67.82 | < 00.001 |

| NLR | 0.606 | 0.524 - 0.685 | 3 | 70.77 | 50.57 | 0.025 |

| MDF | 0.816 | 0.745 - 0.874 | 25.33 | 64.62 | 90.80 | 0.036 |

Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristics; CI, confidence interval; CP, Child-Pugh; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; ABIC, age-bilirubin-international normalized ratio-creatinine; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; MDF, Maddrey’s discriminant function.

4.3. Performance of the Six Scoring Systems in Predicting 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-Month Mortality Depending on Compensated and Decompensated Status

Diagnostic accuracies of six scoring systems were further analyzed depending on compensated and decompensated status. For compensated ALC patients, no patients died within six months. For predicting 12-month and 24-month mortality of compensated ALC patients, the MELD score showed a superior prognostic accuracy with AUROCs of 0.993 (95% CI: 0.864 - 1.000) and 0.870 (95% CI: 0.734 - 0.878). For decompensated ALC patients, the MELD score was significantly better than all the other scores in predicting 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month mortality with the AUROCs of 0.863, 0.855, 0.805, and 0.814, respectively. However, for 1-month mortality in decompensated ALC patients, MDF (AUROC: 0.958; 95% CI: 0.907 - 0.986, P < 0.001) was slightly better than MELD score (AUROC: 0.893; 95% CI: 0.825 - 0.924, P = 0.001; Table 3).

| Survival Months and Scores | Area Under ROC Curve | 95% CI | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compensated | Decompensated | Compensated | Decompensated | Compensated | Decompensated | |

| 1 | ||||||

| CP score | - | -0.717 | - | -0.629 to 0.794 | - | 0.074 |

| MELD | - | -0.893 | - | -0.825 to 0.924 | - | 0.001 |

| ALBI | - | -0.876 | - | -0.804 to 0.928 | - | 0.002 |

| ABIC | - | -0.732 | - | -0.645 to 0.807 | - | 0.056 |

| NLR | - | -0.470 | - | -0.438 to 0.620 | - | 0.807 |

| MDF | - | -0.958 | - | -0.907 to 0.986 | - | < 0.001 |

| 3 | ||||||

| CP score | - | -0.589 | - | -0.491 to 0.677 | - | 0.295 |

| MELD | - | -0.863 | - | -0.790 to 0.918 | - | < 0.001 |

| ALBI | - | -0.635 | - | -0.544 to 0.720 | - | 0.111 |

| ABIC | - | -0.800 | - | -0.719 to 0.867 | - | < 0.001 |

| NLR | - | -0.597 | - | -0.506 to 0.684 | - | 0.252 |

| MDF | - | -0.772 | - | -0.688 to 0.843 | - | 0.001 |

| 6 | ||||||

| CP score | - | -0.652 | - | -0.510 to 0.793 | - | 0.040 |

| MELD | - | -0.855 | - | -0.756 to 9.953 | - | < 0.001 |

| ALBI | - | -0.680 | - | -0.526 to 0.833 | - | 0.015 |

| ABIC | - | -0.827 | - | -0.721 to 0.932 | - | < 0.001 |

| NLR | - | -0.596 | - | -0.454 to 0.738 | - | 0.194 |

| MDF | - | -0.756 | - | -0.624 to 0.889 | - | 0.068 |

| 12 | ||||||

| CP score | 0.513 | 0.634 | 0.318 to 0.705 | 0.543 to 0.719 | 0.941 | 0.020 |

| MELD | 0.993 | 0.805 | 0.864 to 1.000 | 0.724 to 0.871 | 0.006 | < 0.001 |

| ALBI | 0.773 | 0.648 | 0.577 to 0.909 | 0.557 to 0.731 | 0.128 | 0.011 |

| ABIC | 0.507 | 0.620 | 0.312 to 0.699 | 0.529 to 0.706 | 0.970 | 0.038 |

| NLR | 0.613 | 0.572 | 0.412 to 0.790 | 0.480 to 0.660 | 0.528 | 0.216 |

| MDF | 0.950 | 0.752 | 0.877 to 0.998 | 0.667 to 0.825 | 0.005 | < 0.001 |

| 24 | ||||||

| CP score | 0.570 | 0.598 | 0.370 to 0.754 | 0.506 to 0.685 | 0.631 | 0.059 |

| MELD | 0.870 | 0.814 | 0.689 to 0.966 | 0.734 to 0.878 | 0.033 | < 0.001 |

| ALBI | 0.813 | 0.708 | 0.621 to 0.934 | 0.619 to 0.786 | 0.013 | < 0.001 |

| ABIC | 0.609 | 0.679 | 0.407 to 0.786 | 0.589 to 0.760 | 0.453 | 0.001 |

| NLR | 0.557 | 0.583 | 0.358 to 0.743 | 0.491 to 0.671 | 0.697 | 0.110 |

| MDF | 0.861 | 0.797 | 0.678 to 0.962 | 0.716 to 0.864 | 0.011 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: ROC, receiver operating characteristics; CI, confidence interval; CP, Child-Pugh; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; ABIC, age-bilirubin-international normalized ratio-creatinine; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; MDF, Maddrey’s discriminant function.

4.4. Evaluation of Independent Prognostic Factors of All-Cause Mortality in Alcoholic Liver Cirrhosis Patients

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis were conducted to assess the association between all-cause mortality and baseline variables, laboratory metrics, complications, and six score systems. Initially, univariate Cox regression analysis was performed to identify prognostic risk factors. Many baseline clinical covariates were associated with the risk for all-cause mortality in univariate analysis (P < 0.05), except for age (P = 0.058). Variables with P < 0.1 were included in the multivariate Cox regression. Age [hazard ratio (HR): 1.142, 95% CI: 1.002 - 1.302; P = 0.047], MDF (HR: 1.022, 95% CI: 1.000 - 1.045; P = 0.049), and MELD (HR: 1.175, 95% CI: 1.073 - 1.286; P = 0.001) remained significant in multivariate analysis (Table 4).

| Variables | Univariates Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-Value | HR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Age (y) | 1.020 (0.999 - 1.040) | 0.058 | 1.142 (1.002 - 1.302) | 0.047 |

| HGB (g/L) | 0.986 (0.979 - 0.993) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 0.995 (0.991 - 0.999) | 0.020 | - | - |

| ALB (g/L) | 0.939 (0.906 - 0.973) | 0.001 | - | - |

| CREA (mmol/L) | 1.007 (1.004 - 1.009) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| PT (s) | 1.084 (1.057 - 1.110) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| INR | 2.242 (1.747 - 2.878) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| TBIL (mmol/L) | 1.008 (1.005 - 1.011) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Ascites | 1.043 (0.602–1.806) | 0.882 | - | - |

| HE | 0.439 (0.320–0.603) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| GI bleeding | 1.311 (0.762 - 2.256) | 0.328 | - | - |

| Infection | 1.345 (1.007 - 1.680) | 0.009 | - | - |

| MDF | 1.017 (1.012 - 1.023) | < 0.001 | 1.022 (1.000 - 1.045) | 0.049 |

| NLR | 1.816 (1.180 - 2.797) | 0.007 | - | - |

| CP score | 1.743 (1.247 - 2.433) | 0.001 | - | - |

| MELD | 1.169 (1.130 - 1.211) | < 0.001 | 1.175 (1.073 - 1.286) | 0.001 |

| ABIC | 1.634 (1.356 - 1.968) | < 0.001 | - | - |

| ALBI | 2.736 (1.835 - 4.078) | < 0.001 | - | - |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; HGB, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet count; ALB, albumin; CREA, creatinine; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; TBIL, total bilirubin; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; GI, gastrointestinal; MDF, Maddrey’s discriminant function; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; CP, Child-Pugh; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; ABIC, age-bilirubin-international normalized ratio-creatinine; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin.

4.5. Survival Curves by the Kaplan-Meier Analysis

Subsequently, the overall survival of ALC patients was evaluated by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Ninety-three patients died during the follow-up period, including eight patients in the compensated group and eighty-five patients in the decompensated group. All deaths were liver-related. Kaplan-Meier survival curve showed that decompensated ALC had a worse prognosis (χ2 = 13.21, P < 0.001). We also analyzed the relationship between all-cause mortality and MELD score. The cut-off value of the MELD score was selected upon the ROC curve and Youden’s Index at 12 months. The optimal cut-off point for the MELD score was 7, with 78.95% sensitivity and 73.68% specificity. According to the best cut-off, patients were divided into a high MELD group and a low MELD group. The Kaplan-Meier curve showed that patients in the high MELD score group (χ2 = 49.31, P < 0.001) had a higher mortality (Figure 3).

5. Discussion

Prognostic evaluation of ALC patients remains an important challenge in clinical decision-making. Accurate prediction of prognosis is essential to plan the best treatment program as well as the choice of major procedures for ALC patients. Currently, several simple scoring systems have been widely used in clinical practice to evaluate the prognosis of ALC. However, it is still an open question which is the most appropriate scoring system for evaluating the prognosis of ALC. To the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to better assess the appropriate score for the prognosis of ALC patients.

In this study, we compared the prognostic accuracy of six score systems commonly used for ALC. We confirmed that, overall, the MELD score performed better than the other five scoring systems to predict short-term and long-term mortality for ALC. Of note, for 1-month mortality, both MELD score and MDF exhibited a high predictive power, consistent with a study by Kadian et al. that showed that both MELD and MDF had strong and equally predictive power for 28-day survival (20). However, a global study involving 85 tertiary centers in 11 countries and 2581 AH patients showed that the AUROCs for 28-day mortality were 0.776 for MELD and 0.701 for MDF, respectively, and concluded that the MELD score has the best performance in predicting short-term mortality (13). The reason may be that the number of patients enrolled in our study was relatively small. For 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month survival, the MELD score showed a significantly higher prediction capacity than all the other five scores in ALC patients. We demonstrated that the MELD score had a superior performance than the other five scores for short-term and long-term mortality. Our results are consistent with previous studies. For example, a longitudinal study of 110 patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis showed that the MELD score had a positive predictive value of 93.6% and sensitivity of 72.7% with the AUROC of 0.926 for 1-month mortality (21). A prospective observation study of 216 consecutive cases of liver cirrhosis patients showed that the MELD score was superior to the CP score in predicting survival (22). Similarly, a study of 308 patients with liver cirrhosis showed that MELD was the best predictor of mortality in outpatients with cirrhosis (23).

In our study, the MELD score was significantly better than the other five scores in predicting 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-month survival of decompensated ALC patients. Our finding was in accordance with a study that demonstrated the MELD score had the best discriminative ability for identifying ALC patients with a high mortality risk (24). In multivariate analysis, we found that age, MELD, and MDF were independent prognostic factors. In agreement with our study, a study found that MELD was significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (25).

The MELD score was widely used in cirrhotic patients. Nevertheless, different liver cirrhosis etiologies exhibited different pathogenesis, which may have different prognoses and outcomes. A series of studies were dedicated to evaluating the appropriate score for different etiology of liver cirrhosis (26-29). A study of 5,138 cirrhosis patients revealed that compared to non-ALC, ALC patients were more often with high liver-related complications and had higher mortality after hospitalization (30). Currently, several studies have explored effective and simplified scores for the prognostic assessment of ALC patients. A multicenter prognostic cohort study performed in Korea enrolled 1,096 ALC patients and compared the predictive abilities of MELD, MELD-Na, and MELD 3.0, but showed that the differences were not statistically significant (31). Moreover, a recent study analyzed 316 hospitalized ALC patients with non-severe alcoholic hepatitis (Non-SAH) from the Korean Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure cohort and developed a new prognostic model with four variables: Vasopressor use, neutrophil proportion > 70%, past deterioration, and Na < 128 mmol/L, which may accurately predict the prognosis of ALC patients with non-SAH (32). Another study evaluated the role of inflammatory biomarker NLR in predicting 30-day mortality in ALC patients and found that NLR had a similar prognostic value to MELD (33). However, our study failed to show a high prognostic ability of NLR in predicting short-term and long-term mortality of ALC patients. This may be explained by a relatively small number of ALC patients enrolled in our study. In addition, a case-control study evaluated the prognostic ability of NLR in cirrhosis patients and showed that NLR was significant in predicting liver-related mortality in NLR ≥ 4 and NLR ≥ 6.8 groups. However, in NLR ≥ 1.9 group, NLR showed a low predictive ability (34). In addition, a study reported that NLR with an optimal cut-off of > 1.95 had a sensitivity of 84.75% and specificity of 93.91% in predicting complications during the 1-year follow-up (35). The median NLR in our study was 3.43, indicating that most enrolled patients were in a low level of NLR, which may also affect the results to a certain extent.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study performed in a single tertiary hospital, so selection bias could not be avoided. Second, a relatively small number of patients were enrolled in our study. Finally, no female ALC patients were included in this study since the incidence of ALC is extremely low in females.

5.1. Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that MELD was generally a reliable and superior prognostic score system in predicting short-term and long-term mortality for male ALC patients, except that MDF was slightly better than MELD in predicting 1-month mortality. Our findings help confirm the accuracy of noninvasive scoring systems for ALC patients.