1. Background

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the primary causes of disease and mortality worldwide and has significant detrimental effects on the economy, society, and health (1, 2). The clinical features of ALD often begin with early hepatic lipid accumulation, progressing to inflammation, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (3, 4). Chronic alcohol consumption is responsible for 2.5 million deaths annually, resulting in a mortality rate of 5.9% (5, 6). The ALD may arise through various molecular pathways associated with oxidative stress, genetics, environmental, dietary, and immunological stress (7). However, oxidative stress and inflammation play a significant role in the molecular etiology of ALD.

Alcohol-metabolizing enzymes in the liver, such as alcohol dehydrogenase, convert approximately 90% of consumed alcohol into acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde, the primary toxic metabolite of alcohol metabolism, can form covalent bonds with DNA, proteins, and lipids, resulting in adduct formation and DNA damage (8). Activation of cytochrome P450 by this process generates oxidants, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Oxidative damage caused by these oxidants leads to inflammation, fibrogenesis, and cell injury (9, 10). Oxidative stress results from an intracellular imbalance characterized by increased oxidant production and decreased antioxidant synthesis (5). Enzymatic antioxidant defense systems, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), along with non-enzymatic systems including beta-carotene, bilirubin, and vitamins A, C, and E, are essential for protecting cells from oxidants under normal conditions (9, 11).

As previously described, chronic alcohol consumption increases ROS levels in neutrophils, Kupffer cells, and parenchymal cells, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and subsequent inflammation (4, 12). Kupffer cells, the liver-resident macrophages, are among the first agents of inflammation, infiltrating the liver parenchyma and inducing local production of pre-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which trigger inflammatory responses and signaling pathways (2, 13). The TNF-α is a pleiotropic cytokine that induces inflammation and cytotoxicity, promoting liver fibrogenesis, regeneration, apoptosis, and cell necrosis (14, 15).

Alcohol-induced liver damage is an increasing health issue in human societies. Consequently, extensive research has focused on the use of various extracts and medicinal herbs to counteract this phenomenon; however, no permanent or comprehensive treatment for alcohol-induced liver damage has been identified.

Herbal medicines have attracted scientific interest as alternatives to pharmaceutical therapies due to their greater biocompatibility and lower risk of adverse effects. According to the World Health Organization, Stachys pilifera Benth, also known as "Marzeh Kuhi", is a commonly used medicinal herb in Iran. Stachys pilifera Benth is a perennial species in the Labiatae family, commonly found in highland regions (16). Phytochemical studies of Stachys species have confirmed the presence of phenylpropanoids, phytosterols, glucosides, flavonoids, acetophenones, fatty acids, iridoids, diterpenes, alkaloids, lignans, triterpenes, phenolic acids, sesquiterpenes, phenylethanoid glycosides, and polysaccharides (16-20). The major secondary metabolites from phytochemically screened Stachys species include iridoids, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and fatty acids (17, 20-23). Few studies have investigated the phytochemical components of S. pilifera Benth extracts. Identified constituents include terpenes, phenolic compounds, and alkaloids (24). The major compounds in the S. pilifera Benth ethanolic extract are 3,7,11,16-tetramethyl (24.77%), hexadeca-2,6,10,14-tetraen-1-ol, thymol (14.1%), and linolenic acid (13.4%) (25). Asfaram et al. reported thymol and carvacrol in the S. pilifera Benth methanolic extract (26), and terpenoid and alkaloid fractions have also been isolated from the S. pilifera Benth methanolic extract (24).

These phytochemical compounds have been used in herbal medicine for their potential to treat various illnesses. Previous reviews suggest that diterpenoids in the roots and aerial parts of Stachys species are biologically active (17, 27). Biological tests have demonstrated that compounds in this plant not only protect the liver and kidneys (25, 28), but also possess antioxidant (12, 25), anti-inflammatory (29), anticancer (22, 30), antibacterial, anti-hepatitis (28), and immunoregulatory effects (31). Stachys is commonly used in herbal medicine to treat dermatitis, anxiety, digestive disorders, genital tumors, and infections in many countries (32). Stachys pilifera Benth is an endemic species in Iran, traditionally used to treat ailments such as toothache, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and as an analgesic, expectorant, and antiseptic, particularly for seasoning foods and gynecological infections (16, 33). Studies indicate that phenolic compounds in the S. pilifera Benth extract may control inflammation by preventing lipid peroxidation, leukocyte infiltration, and synthesis of pro-inflammatory chemicals (34, 35). Alcohol consumption induces oxidative stress, which activates inflammatory signaling pathways and factors leading to liver damage and dysfunction in both clinical and laboratory settings.

2. Objectives

In this study, a model of alcohol-induced liver damage was established to investigate the effects of S. pilifera Benth extract on oxidative stress and inflammatory processes, with the aim of addressing EtOH-induced liver damage.

3. Methods

3.1. Drugs and Chemicals

Pentobarbital, thiobarbituric acid (TBA), and 5,5′-dithiols-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO, USA). Trichloroacetic acid (TCA), 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH), and formaldehyde were procured from Merck (Germany).

3.2. Plant Material and Extraction

In spring 2023, aerial parts of S. pilifera Benth were collected from Kakan, Yasuj, Kohgiluyeh and Boyar Ahmad, Iran (herbarium No. 1897). Dr. Azizollah Jafari, Department of Botany, Centre for Research in Natural Resource and Animal Husbandry, Yasuj University, Yasuj, Iran, authenticated the samples and archived a voucher specimen (herbarium No. 1897). The plant material was protected from sunlight, cleaned, dried, and crushed. For extraction, 100 g of plant powder was soaked in 1000 mL of 70% EtOH (Yasan, Iran) at room temperature for 72 hours, based on previous studies (25, 28). The mixture was filtered, and the extract was concentrated by vacuum rotary evaporation (Hyedolph, Heizbad Hei-VAP, Germany) at 40°C under low pressure. The extract was dried and stored at -20°C for further use.

3.3. Experimental Design and Procedure

Forty male Wistar rats (eight weeks old, 200 - 250 g) were obtained from the Animal Centre of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences’ School of Medicine (Yasuj, Iran). The animals were acclimatized for seven days in a controlled environment (22 ± 2°C, 12-hour light/dark cycle, 55 - 60% humidity) with free access to food and water. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences (IR.YUMS.AEC.1401.006) and conducted in accordance with the Law of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No.86-23). The rats were randomly assigned to four groups (25, 28):

- Normal control group: Seven mL/kg body weight of normal saline orally for 35 days

- Ethanol group (EtOH): Seven mL/kg body weight of normal saline orally for 35 days, followed by 7 mL/kg body weight of 40% (v/v) alcohol after two hours

- Ethanol-Stachys pilifera Benth group (SP+EtOH): Daily alcohol treatment for 35 days, followed by S. pilifera Benth extract (400 mg/kg body weight) orally after two hours (12).

- Stachys pilifera Benth group: A dose of 400 mg/kg body weight of SP extract was administered orally for 35 days.

At the end of day 35, animals were weighed. Twelve hours after the final oral dose, the animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg body weight), blood samples were collected, and the animals were sacrificed. Blood was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes, and serum was stored at -20°C for biochemical analysis. Liver tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis. Other liver sections were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 4.7, 50 mM/L) and stored at -20°C for further analysis. The final portion was frozen in liquid nitrogen at -80°C for gene expression analysis (6, 36).

3.4. Biochemical Analysis

Liver function was evaluated using a colorimetric method to measure alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT), total protein (TP), total bilirubin (TBIL), albumin (ALB), triglyceride (TG), and cholesterol (CHO). Commercial diagnostic kits were obtained from Bionic Diagnostic Company (Tehran, Iran) and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

3.5. Estimation of Oxidative Stress Parameters

3.5.1. Measurement of Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power

Total plasma antioxidant capacity was assessed using the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, following the Benzie and Strain method. This procedure involves the reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ in an acidic environment and formation of a blue Fe2+-tripyridyl-triazine (TPTZ) complex in the presence of electron-donating antioxidants. The color intensity was measured spectrophotometrically at 593 nm (37).

3.5.2. Measurement of Total Thiol

Total thiol (T-SH) was quantified spectrophotometrically based on the reaction of DTNB with thiol groups to produce the yellow compound 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoic acid (2).

3.5.3. Measurement of Protein Carbonyl

Protein carbonyl (PCO) concentrations were measured using the method described by Dalle-Donne et al. (38), involving reaction of carbonyl groups with DNPH. After incubation with DNPH and HCl, samples were centrifuged, washed with EtOH/ethyl acetate, and resuspended in guanidine solution. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm, and PCO content was calculated using a molar absorption coefficient of 2.2 × 104 M-1 cm-1 (25).

3.5.4. Measurement of Malondialdehyde

Malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation, was measured by the reaction with TBA. Tissue samples (200 μL) were mixed with 1 mL TBA-TCA reagent, heated at 90°C for 30 minutes, cooled at 4°C for 5 minutes, and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 minutes. The absorbance of the pink chromogen was measured at 535 nm, and results were expressed as nanomoles per gram of tissue (39).

3.5.5. Measurement of Nitric Oxide Metabolite

Nitrite, a stable metabolite of nitric oxide (NO), was quantified using the Griess reagent method, as NO is unstable and rapidly converts to nitrate and nitrite.

3.6. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

The CAT and SOD levels in blood were measured using colorimetric enzymatic test kits (Karmania Pars Gene, Kerman, Iran), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured using an ELISA reader, and results were calculated from standard curves.

3.7. Determination of Cytokines

Levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were measured using ELISA kits (Carmania Pars Gene, Kerman, Iran) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Interleukins were measured in picograms per milliliter, and absorbance was read at 450 nm using an ELISA reader.

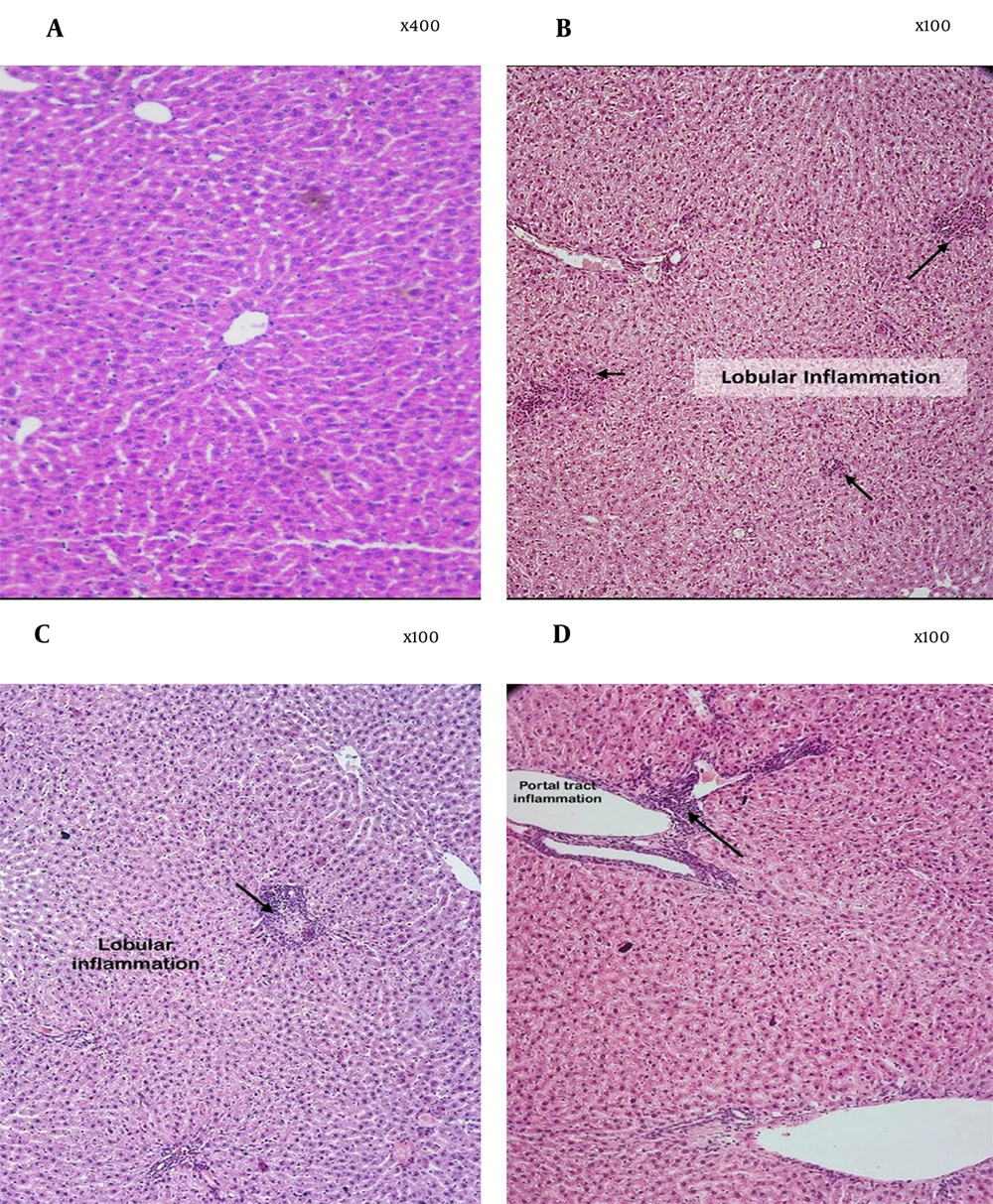

3.8. Histopathological Analysis

Liver tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5 μm slices using a rotary microtome. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under a light microscope. Pathological changes were scored as none (0, no pathological change), mild (1, one focus per low power field), moderate (2), or severe (3) based on the extent of inflammation and necrosis (40).

3.9. RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR was used to assess TNF-α gene expression. Liver tissue was homogenized, and total RNA was extracted using RNX Plus (Sinaclon, Tehran, Iran). cDNA was synthesized using a cDNA synthesis kit (Sinaclon, Tehran, Iran). Primer sequences were as follows: GAPDH, F: 5'-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3', R: 5'-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3'; TNF-α, F: 5'-GGTGATCGGTCCCAACAAGGA-3', R: 5'-CACGCTGGCTCAGCCACTC-3'. The TNF-α and IL-6 gene expression was measured using the Rotor Gene 3000 (Bio-Rad, USA) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). The PCR cycling was performed for forty cycles: Thirty seconds at 58°C, 30 seconds at 72°C, and 15 seconds at 95°C. Relative mRNA expression was calculated relative to GAPDH using the 2-ΔCt method (6).

3.10. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical significance among groups was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for liver histological evaluation. Data are presented as Mean±SEM. A significance criterion of P-value ≤ 0.05 was used in all analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Effects of Stachys pilifera Benth on Biochemical Parameters

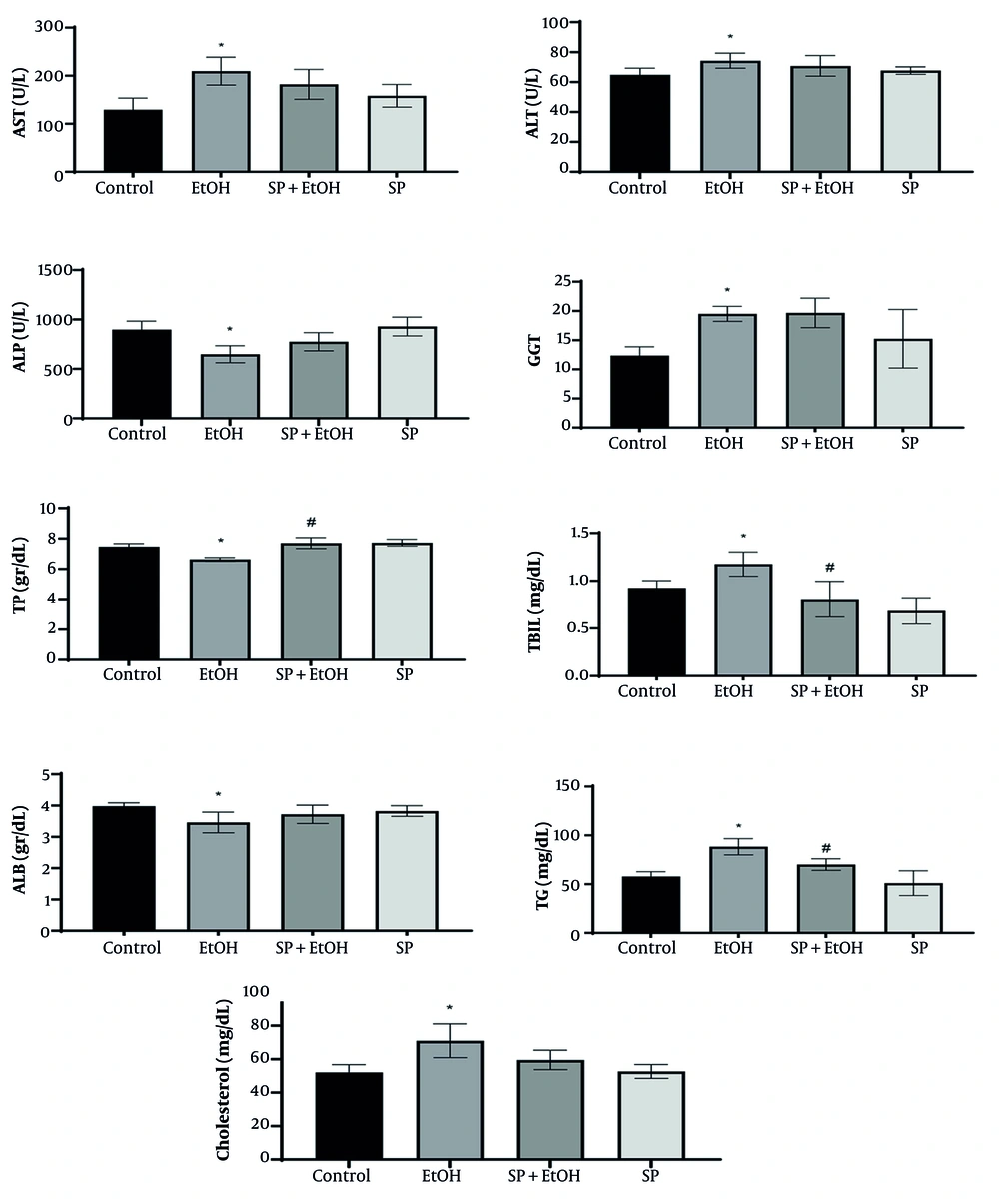

Serum biochemical markers, including AST, ALT, ALP, GGT, TBIL, TG, TP, ALB, and CHO, are useful for diagnosing early liver damage. Figure 1 illustrates the variation of these markers among the groups. Rats exposed to alcohol exhibited significantly higher serum levels of AST, ALT, GGT, TBIL, TG, and CHO compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.05), indicating impaired liver function (Figure 1). Additionally, TP and ALB levels in the EtOH group were significantly lower (P ≤ 0.05) than in the control group. Notably, administration of S. pilifera Benth extract significantly increased TP and reduced TG and TBIL levels (P ≤ 0.05) compared to the EtOH group. However, ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, ALB, and CHO levels in the EtOH and SP+EtOH groups did not significantly differ.

Effects of Stachys pilifera Benth extract on biochemical markers in serum in rats with alcohol-induced liver injury (Abbreviations: TP, total protein; TBIL, total bilirubin; ALB, albumin; TG, triglycerides; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; SP+EtOH, ethanol-Stachys pilifera Benth; EtOH, ethanol). Data are expressed as mean±SEM. * Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between control and EtOH groups, # significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between SP+EtOH and EtOH groups. A P-value ≤ 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

4.2. Effects of Stachys pilifera Benth on Liver Oxidative Stress Markers

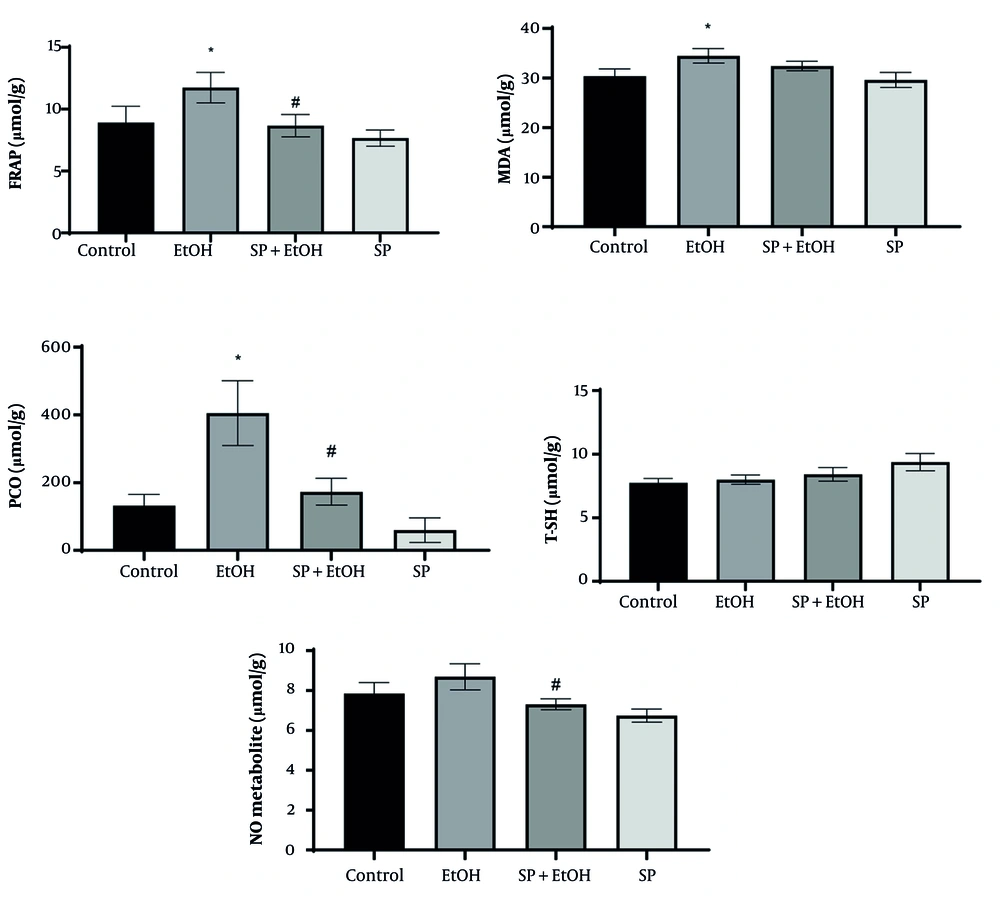

As shown in Figure 2, the EtOH group exhibited significantly higher levels of FRAP, PCO, and MDA compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.05). While NO levels increased insignificantly compared to control, S. pilifera Benth significantly reduced NO. Oral administration of 400 mg/kg S. pilifera Benth extract for 35 days significantly decreased oxidative stress markers (PCO and FRAP, P ≤ 0.05). Hepatic MDA and T-SH levels did not significantly change compared to the EtOH group.

Effects of Stachys pilifera Benth extract on markers of oxidative stress in rat livers after alcohol-induced liver damage (Abbreviations: FRAP, ferric reducing antioxidant power; MDA, malondialdehyde; PCO, protein carbonyl; T-SH, total thiol; NO, nitric oxide; SP+EtOH, ethanol-Stachys pilifera Benth; EtOH, ethanol). Data are expressed as mean±SEM. * Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between control and EtOH groups, # significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between SP+EtOH and EtOH groups. A P-value ≤ 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

4.3. Effects of Stachys pilifera Benth on Antioxidant Enzyme Activities

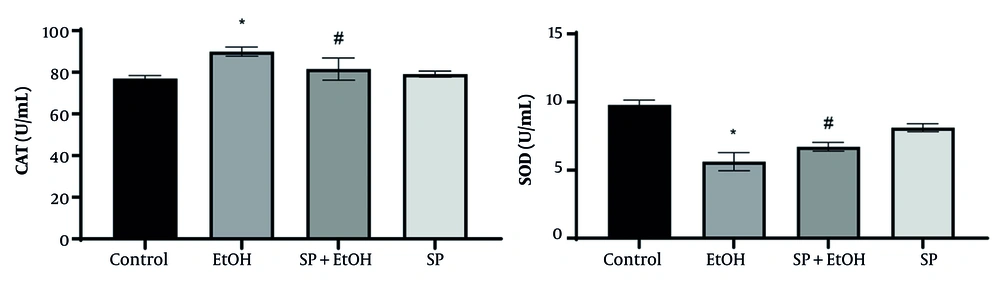

Figure 3 shows the activity levels of liver antioxidant enzymes. The EtOH group had significantly higher CAT activity and markedly reduced SOD activity compared to the control group (P ≤ 0.05). Stachys pilifera Benth extract treatment significantly increased SOD activity and restored SOD levels. While CAT activity in S. pilifera Benth-treated rats remained higher than controls, it was significantly lower than in the EtOH group (P ≤ 0.05).

Effect of Stachys pilifera Benth extract on catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, the antioxidant enzymes in serum of rats with alcohol-induced liver damage (Abbreviations: SP+EtOH, ethanol-Stachys pilifera Benth; EtOH, ethanol). Data are expressed as mean±SEM. * Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between control and EtOH groups, # significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between SP+EtOH and EtOH groups. A P-value ≤ 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

4.4. Effects of Stachys pilifera Benth on Hepatic Inflammatory Markers

Levels of inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were evaluated to further investigate the protective mechanism of S. pilifera Benth (Table 1). All EtOH groups exhibited significantly higher TNF-α and IL-6 levels than the control group (P ≤ 0.05). The IL-1β was also upregulated, though not significantly. Rats treated with S. pilifera Benth had markedly lower IL-6 and TNF-α levels than those given EtOH (P ≤ 0.05), indicating that S. pilifera Benth protected ALD rats against inflammation.

Abbreviations: TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-6, interleukin-6; EtOH, ethanol; SP+EtOH, ethanol-Stachys pilifera Benth.

a Values are expressed as mean±SEM, pg/mL.

b Cytokine markers: The IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α.

c Significance level: P-value ≤ 0.05.

d Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between EtOH and control groups.

e Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between EtOH and SP+EtOH groups.

4.5. Gene Expression of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α

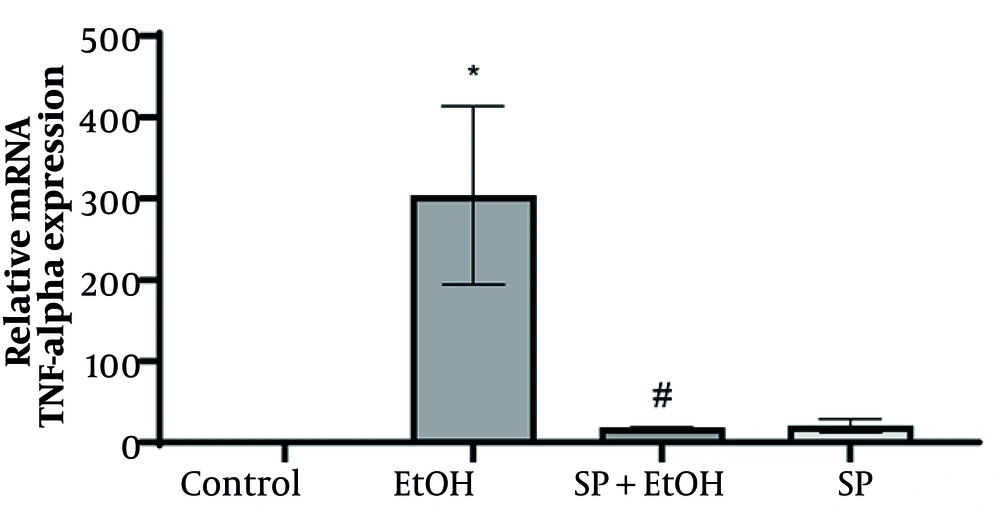

To further assess the efficacy of S. pilifera Benth extract, TNF-α mRNA expression in the liver was measured using real-time PCR. The EtOH group exhibited a significant increase in TNF-α relative expression compared to the control group. Stachys pilifera Benth extract significantly reduced TNF-α gene expression in EtOH rats (Figure 4).

Effect of Stachys pilifera Benth on tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) mRNA levels in rats with alcohol-induced liver damage (Abbreviations: SP+EtOH, ethanol-Stachys pilifera Benth; EtOH, ethanol). Data are expressed mean ± SEM. * Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between control and EtOH groups, # significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between SP+EtOH and EtOH groups. A P-value ≤ 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

4.6. Histopathological Analysis of the Liver

Liver tissue samples from each group were evaluated histopathologically after H&E staining (Table 2 and Figure 5). The control group displayed homogeneous hepatocellular architecture with central lobular veins, radiating hepatic cords, clear hepatic sinusoids, intact cytoplasm, and centrally located nuclei, with no pathological changes. In contrast, the EtOH group showed signs of apoptosis, irregular lobular architecture, hepatocyte ballooning, degeneration, and infiltration of inflammatory cells, indicating inflammation-related liver damage. Notably, S. pilifera Benth treatment resulted in the greatest restoration of these pathological abnormalities.

| Groups | Steatosis | Ballooning Degeneration | Lobular Inflammation | Portal Inflammation | Portal Tract Fibrosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EtOH | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| SP+EtOH | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Stachyspilifera Benth | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Abbreviations: EtOH, ethanol; SP+EtOH, ethanol-Stachys pilifera Benth.

a Steatosis, ballooning degeneration, lobular inflammation, portal inflammation, and portal tract fibrosis were quantitatively evaluated.

b A P-value ≤ 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to assess the protective effects of S. pilifera Benth extract against alcohol-induced liver damage in rats. The results confirmed that S. pilifera Benth provided hepatoprotective benefits by reducing both oxidative stress markers and inflammatory responses through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

The liver, which regulates numerous physiological processes, is the primary organ for alcohol metabolism. Excessive alcohol consumption leads to ALD, characterized by inflammation, hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, along with progressive liver damage (5, 41). Despite advances in pharmacotherapies, no comprehensive targeted therapy is available. Medicinal herbs and their bioactive phenolic and flavonoid constituents have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anti-hepatitis, antioxidant, and anti-apoptotic properties, suggesting their potential for ALD treatment (6, 34). To our knowledge, the therapeutic potential of S. pilifera Benth extract for ALD has not yet been investigated.

From a clinical perspective, the most important standard parameters for liver function tests and the most useful biochemical and physiological indicators of hepatotoxicity are aminotransferase activities, TBIL, TP, and ALB. Chronic alcohol consumption leads to structural changes in liver tissue, including alterations to membrane proteins, reduced structural stability, increased membrane permeability, and eventual cell breakdown, resulting in the release of AST, ALT, ALP, GGT, and TP into the bloodstream (10, 42). The present data are consistent with previous studies and predictions (9, 43). The GGT, a plasma membrane enzyme, is essential for glutathione homeostasis. Increased oxidized glutathione and hepatic GGT promote extracellular GSH metabolism, with γ-glutamyl peptides converted to precursor amino acids for intracellular GSH synthesis (44, 45). Therefore, GGT is closely linked to liver status in ALD diagnosis. No significant difference in GGT activity was observed between the EtOH and SP+EtOH groups.

Alcohol-induced liver damage is also associated with elevated serum TG and CHO, considered markers of steatosis (36). Moslemi et al. (12) demonstrated that S. pilifera Benth extract prevented the decrease in serum ALB and the increase in TBIL and hepatic enzyme activity induced by bile duct ligation (BDL), consistent with our findings. The current study demonstrated the hepatoprotective effects of S. pilifera Benth against alcohol-induced liver impairment. These biochemical markers suggest that S. pilifera Benth extract ameliorates alcohol-induced liver damage through liver parenchyma improvement, liver cell regeneration, and cell membrane stabilization. The hepatoprotective effect was further supported by histopathological examination, which revealed that S. pilifera Benth treatment dramatically reduced alcohol-induced pathological changes such as apoptosis, ballooning degeneration, lobular and portal inflammation, and inflammatory cell infiltration.

Oxidative stress and subsequent inflammatory activation influence the pathological progression of alcohol-induced liver injury (46). The EtOH administration increases ROS production, overwhelming antioxidant defenses and promoting oxidative stress. During hepatic alcohol metabolism, free radical mediators attack proteins, lipids, and membrane components, resulting in lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, apoptosis, and cell necrosis (13, 47). To clarify the mechanism of S. pilifera Benth’s protective effect, several oxidative stress mediators were assessed. The ROS-induced lipid peroxidation produces MDA, a cytotoxic product and biomarker of tissue damage (48). Stachys pilifera Benth treatment produced a slight, non-significant reduction in MDA levels. Zarezade et al. (29) reported that S. pilifera Benth extract significantly reduced serum and liver MDA concentrations but did not affect TNF-α or IL-1β in paw tissues. The extract also suppressed heat- or hypotension-induced hemolysis in human red blood cells (50 - 800 g/mL). The authors hypothesized that S. pilifera Benth’s anti-inflammatory properties were not related to TNF-α or IL-1β, but to inhibition of lysosomal membrane stability, lipid peroxidation, and leukocyte infiltration (29). Stachys pilifera Benth hydroalcoholic extract contains 660.79 ± 10.06 mg RE/g extract of total flavonoids and 101.35 ± 2.96 mg GAE/g extract of total phenols (29). Significant reductions in serum and liver MDA levels were observed in formalin and carrageenan tests. Thus, S. pilifera Benth likely inhibits lipid peroxidation and exerts anti-inflammatory effects through its antioxidant activities. Phytochemical data confirm the presence of flavonoids and phenols in the plant (29). Ample evidence indicates that flavonoids and phenolic compounds inhibit inflammation by regulating pro-inflammatory molecule production (49). Therefore, the phenolic and flavonoid content of S. pilifera Benth likely contributes to its anti-inflammatory activity (29, 50). Carvacrol and thymol, present in S. pilifera Benth, also have immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties (51, 52), suggesting that these compounds may underlie S. pilifera Benth’s anti-inflammatory effects (32).

The ROS-induced changes in the EtOH group included increased PCO, a key marker of oxidative stress from protein interaction with free radicals. This finding aligns with Du et al. (2), who observed increased protein oxidative damage after EtOH exposure. Proteins, often serving as intracellular enzymes, are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress (28). Our previous clinical work (12) found that PCO levels decreased after S. pilifera Benth extract treatment in BDL+SP groups, supporting the hypothesis that S. pilifera Benth’s tannins, saponins, and flavonoids function as natural regulators of oxidative stress.

Recent studies have linked NO to alcohol-induced liver injury. Kupffer and endothelial cells generate NO in response to stimuli, which rapidly combines with superoxide anion to form peroxynitrite, damaging DNA, proteins, and lipids (25, 53). In this study, NO levels increased in the EtOH group after 35 days, consistent with Liu et al. (43). Stachys pilifera Benth extract significantly reduced NO levels compared to the EtOH group, consistent with Danaei et al. (35).

Healthy cells rely on antioxidant enzymes such as CAT, SOD, and GPx to defend against ROS (40). The SOD catalyzes the reduction of superoxide radicals to O2 and H2O2, while CAT breaks down H2O2 into water and oxygen (54, 55). Li et al. (42) reported decreased CAT and SOD activity in ALI mice compared to controls, while other studies found increased CAT activity with chronic alcohol consumption (56). Our results showed reduced SOD and increased CAT activity after EtOH administration, indicating an active defense response. Stachys pilifera Benth extract significantly increased SOD activity, but reduced CAT activity, possibly due to an inability to eliminate increased radicals. The phenolic content of S. pilifera Benth may protect the liver by reducing free radical production, enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity, and decreasing oxidative stress.

Inflammation and immune responses, mediated by ROS, are major triggers of apoptosis in ALD (57). Kupffer and inflammatory cells produce pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β), which activate stellate cells and promote liver fibrosis (58, 59). The TNF-α plays a central role in hepatotoxicity by orchestrating inflammatory signaling (60), and is also involved in liver regeneration along with IL-6 (61). Our findings are supported by studies showing increased TNF-α mRNA and elevated IL-6 and TNF-α levels after alcohol-induced liver damage (62, 63). Previous studies have shown that S. pilifera Benth protects against liver damage via anti-inflammatory effects (12). Our study found that S. pilifera Benth significantly reduced TNF-α and IL-6 levels, as well as TNF-α gene expression in EtOH animals, confirming its anti-inflammatory effect on liver tissue. These findings are consistent with Moslemi et al. (12) and Moini Jazani et al. (64). Such extracts possess potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, effectively reducing oxidative damage in disease models and suggesting a shared therapeutic mechanism. A study by Lee et al. (65) in 2025 would further validate the current research by demonstrating that plant-derived metabolites can counteract chemical-induced damage across different organ systems and toxicants, as geranyl acetate protected skin cells from chemical toxicants by mitigating oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation — mechanisms also targeted by S. pilifera Benth extract in liver cells.

Limitations of this study include the lack of pure plant compound testing, small sample size, use of only male rats, absence of dose-response testing, and lack of behavioral or survival outcomes. Future studies should identify and examine the effects of individual S. pilifera Benth components.

5.1. Conclusions

This study highlights the preventive potential of S. pilifera Benth against alcohol-induced liver damage. The hepatic protective effects of S. pilifera Benth involved regulation of TBIL, TP, and TG, improvement of oxidative status (PCO and FRAP), enhancement of antioxidant capacity (SOD enzyme), modulation of inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6), and inhibition of the inflammatory pathway via down-regulation of TNF-α expression. Morphological changes in liver tissue corroborated the biochemical findings. In conclusion, this experimental study supports further preclinical and clinical investigations of S. pilifera Benth in ALD and suggests new insights for targeted therapeutic strategies to protect the liver.