1. Background

Since the COVID-19 pandemic's start in December 2019, which was brought on by the SARS-CoV-2 beta corona virus. Worldwide, this virus has claimed the lives of millions of people (1). Iran was one of the first nations affected by this pandemic, with more than 7 million coronavirus cases and more than 140000 casualties (2). The most typical symptoms of this illness include sore throat, fever, muscle pain, coughing, and respiratory involvement (3). Other symptoms of the disease that have been seen include cardiovascular complications (4) Neurological symptoms (5). Hematological finding (6) and biochemical changes like changes in some biomarkers including D-dimer (7).

D-dimer is a specific biomarker that shows enhanced activity of the body's fibrinolytic enzymes and activation of the coagulation cascade (8). However, it has high sensitivity but low specificity because it increases in cases such as malignancy, pregnancy, and various infections (9-11).

On the other hand, the increase in inflammation and hypoxia caused by the COVID-19 disease can cause changes in the coagulation profile, including an increase in D-dimer and PT. Increased D-dimer has been linked to mortality and the severity of the COVID-19 disease, according to earlier research (12-14).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine the association of D-dimer with the mortality rate in patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in Hospital. it is possible to reduce the mortality rate of patients hospitalized in the COVID-19 ward by Choosing appropriate treatment.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population and Design

The present research is a cross-sectional study, includes all known COVID-19 patients who visited or were referred to the emergency department of tertiary hospital (Shohada-e Tajrish Educational Hospital) from April 2020 to March 2021.

All patient with positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) who had respiratory and non-respiratory symptoms and signs, are enrolled in the study.

3.2. Data Collection

Demographic information (age and gender of the patient), clinical information [length of hospital stay (LOHS)], having an underlying disease, discharge or death and laboratory data (routine tests have been done at the time of hospitalization, blood clotting profile and D-dimer) were extracted from the electronic medical records of the patients. the inclusion criteria were age above 18 and positive COVID-19 PCR, confirmed using real‐time polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) of throat swab samples. The blood samples for laboratory tests were collected on admission and during the hospitalization. D-dimer were detected using IMMULITE 2000 Immunoassay System system from Siemens company with cutoff 0.5 µg/mL. However, we took into consideration the cut-off of 2000 ng/mL for D-dimer based on other studies in this area of research (15).

3.3. Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the research ethical committee of the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1400.557) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation. The researchers acquired written informed consent and followed the recommendations in Helsinki Declaration.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative variables expressed in the form of mean and standard deviation. Chi-squared test, Fisher exact test, and Student’s t-test were used for nonparametric and parametric analysis, respectively. Statistically significant level was considered as P-value < 0.05 in all analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS V22 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

4. Results

In This Cross-sectional study ,230 patients with an average age of 62.61 ± 15.67 have participated in this descriptive study that was carried out in during 12 months. Among them, 57.82% were men and 42.18% were women. Patients were divided into two groups D-dimer ≥ 2.0 µg/mL with an average age of 67.83 ± 16.73 and D-dimer > 2 µg/mL with an average age of 57.34 ± 16.2.

The research had 230 patients in all, of whom 152 were discharged from the hospital and 78 passed away. The demographic features of the two patient groups, including age and sex, did not significantly differ (P > 0.05). Although the deceased patients' average age is much older than that of the discharged patients, there is no significant difference in terms of gender.

The analysis of 3 indicators of addiction status and smoking and alcohol consumption revealed that the number of smokers and addicts in D-dimer ≥ 2.0 µg/mL group patients were significantly higher than the other group, while the Alcohol Consumption Index did not show a significant difference. But in the study of the death rate, Mortality is significantly higher in addicted people, while there is no significant difference in terms of mortality in smokers and alcoholics.

In the examination of the symptoms caused by the covid disease, it has been shown that in the group D-dimer more than 2 µg/mL coughs in 62 cases, dyspnea in 71 cases, fever in 40 cases, and malaise in 53 cases, and in the other group, respectively, 73,79,65 and 50 cases where there is no significant difference between these two groups.

When the two groups' underlying disorders were compared, the blood pressure in the group with D-dimers greater than 2 µg/mL was 47 against 38 for D-dimers less than 2 µg/mL. diabetes 29 cases against 27, IHD 22 cases against 13, CVA 13 cases against 7, malignancy 18 cases against 2, CKD 8 cases against 4, CABG 7 cases against 6 and COPD 7 cases against 3 for D-dimers less than 2 µg/mL .and there was no significant difference between these two groups.

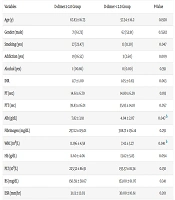

In the analysis of laboratory indicators, serum albumin level and white blood cell count in D-dimer ≥ 2.0 µg/mL group were significantly higher than the other group. But other laboratory indicators including coagulation profile and CRP had no significant difference between the two groups. This is while PT Index, Albumin, White blood cells and CRP were significantly higher in deceased patients than in other groups of patients. Details of this comparison based on D-dimer levels and mortality are provided in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

| Variables | D-dimer ≥ 2.0 Group | D-dimer < 2.0 Group | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 67.83 ± 16.73 | 57.34 ± 16.2 | 0.1928 |

| Gender (male) | 71 (61.73) | 62 (53.91) | 0.5582 |

| Smoking (yes) | 27 (23.47) | 13 (11.30) | 0.047 |

| Addiction (yes) | 19 (16.52) | 3 (2.60) | 0.009 |

| Alcohol (yes) | 1 (00.86) | 0 (0.00) | 0.391 |

| INR | 1.17 ± 1.00 | 1.05 ± 0.83 | 0.063 |

| PT (sec) | 14.61 ± 6.70 | 14.80 ± 6.29 | 0.193 |

| PTT (sec) | 39.83 ± 16.01 | 35.93 ± 14.10 | 0.057 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 7.82 ± 3.91 | 4.04 ± 2.07 | 0.047 b |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 297.12 ± 119.01 | 308.71 ± 136.14 | 0.291 |

| WBC (109/L) | 11.196 ± 4.58 | 7.42 ± 3.27 | 0.041 b |

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.60 ± 4.06 | 13.62 ± 5.83 | 0.094 |

| PLT (109/L) | 223.32 ± 86.91 | 193.57 ± 81.34 | 0.130 |

| BS (mg/dL) | 150.59 ± 58.67 | 153.00 ± 61.07 | 0.341 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 31.13 ± 12.03 | 30.00 ± 10.61 | 0.201 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 38.37 ± 18.93 | 31.44 ± 17.04 | CRP |

| Hospitalization days | 11.85 ± 4.09 | 8.54 ± 3.83 | 0.057 |

| Death (yes) | 62 (53.91) | 16 (13.91) | 0.001 a |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b Significant P-value.

| Variables | Discharge Group | Death Group | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 54.41 ± 16.2 | 70.81 ± 16.73 | 0.044 c |

| Gender (male) | 92 (60.52) | 41 (52.56) | 0.152 |

| Smoking (yes) | 22 (14.47) | 18 (23.07) | 0.091 |

| Addiction (yes) | 11 (7.23) | 11 (14.10) | 0.047 |

| Alcohol (yes) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.28) | 0.391 |

| INR | 1.00 ± 0.71 | 1.22 ± 1.09 | 0.054 |

| PT (sec) | 14.73 ± 6.29 | 14.68 ± 6.74 | 0.18 |

| PTT (sec) | 33.81 ± 14.00 | 41.85 ± 16.27 | 0.040 c |

| Alb (g/dL) | 3.92 ± 2.21 | 7.94 ± 4.08 | 0.041 c |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 334.18 ± 136.14 | 271.65 ± 119.01 | 0.11 |

| WBC (109/L) | 7.83 ± 3.64 | 10.78 ± 4.01 | 0.041 c |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.62 ± 5.83 | 11.60 ± 4.06 | 0.087 |

| PLT (109/L) | 193.57 ± 81.34 | 223.32 ± 86.91 | 0.13 |

| BS (mg/dL) | 153.00 ± 61.07 | 150.59 ± 58.67 | 0.341 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 30.00 ± 10.61 | 31.13 ± 12.03 | 0.201 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 26.49 ± 17.04 | 43.32 ± 18.93 | 0.036 c |

a Values are presented as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b The mortality in the D-Dimer ≥ 2.0 µg/mL group was significantly higher than in the D-dimer > 2.0 µg/mL group, in the analysis of the mortality rate in two groups. Although the average length of hospital stay (LOHS) in the D-dimer ≥ 2.0 µg/mL group was longer, it was not significantly different from the other group.

c Significant P-value.

5. Discussion

D-dimer is a fibrin breakdown product that can be used to diagnose thrombotic diseases because high levels show that secondary fibrinolysis and hypercoagulability are happening in the body. Patients with COVID-19 have been reported to have high coagulability (16, 17). In individuals with severe COVID-19, venous thromboembolism occurs 25% of the time, while pulmonary embolism is detected in 30% of COVID-19 patients (18-20). Patients with ischemic stroke from COVID-19 also had higher blood levels of D-dimer (21). The following are some potential causes of elevated D-dimer values in COVID-19 patients:

(1) Infection can induce pro-inflammatory cytokines to be released, resulting in an inflammatory storm. Notably in individuals with severe COVID-19, pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-2, IL-7, G-CSF, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1A, TNF-α levels in plasma are increased. T-cells, macrophages, and natural killer cells multiply rapidly and are strongly activated, which is accompanied by the overproduction of immune or non-immune defense cells and the release of more than 150 inflammatory cytokines and chemical mediators (22-24). These may cause endothelial cell dysfunction leading to damage to the microvascular system and abnormal activation of the coagulation system, systemic small vessel vasculitis, and extensive microthrombosis.

(2) Various levels of hypoxia are seen in COVID-19 patients. Increased oxygen consumption caused by inflammation can result in thrombosis. Absolute oxygen demand increases during abnormal hemodynamics, which stimulates molecular and cellular pathways and leads to thrombosis (25-28).

(3) Severe infection or acute inflammation caused by sepsis can affect blood coagulation, such as increasing the level of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) and excessive fibrinolysis that eventually activates the coagulation cascade (29, 30).

After grouping the patients based on the D-dimer level, we found that shortness of breath, diabetes, high blood pressure, and cerebrovascular disease can affect the D-dimer level; however, this difference between the two groups was not significant (P > 0.05). There were more male patients in this study than female patients, and smoking history is more prevalent in male patients, which might have an impact. High blood pressure and coronary heart disease may increase the risk of mortality in COVID-19 patients. The relationship with COVID-19 and high blood pressure may be due to ACE2. Pericytes express significant quantities of ACE2 in the heart, according to a recent study. Viral infections can harm pericytes, which can result in capillary cell dysfunction and microvascular malfunction. This seems to explain some of the potential reasons for acute coronary syndrome in COVID-19 patients (31). Cerebrovascular disease and diabetes are risk factors that affect prognosis. Diabetic COVID-19 patients have higher levels of D-dimer, higher inflammatory markers, and worse prognosis than non-diabetic patients (32). Also, this study demonstrated that COVID-19 patients with other underlying illnesses had greater D-dimer levels and a poorer prognosis, although the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). When compared to healthy and discharged patients, those who died with COVID-19 infection were substantially older than other patients, according to an analysis of epidemiological and clinical markers in the current study (P < 0.05). Moreover, this group of COVID-19 patients had significantly higher WBC, Alb, PT, and CRP indices than the other group. The average age of mortality brought on by the novel coronavirus was 69.8 years in Yang et al.'s study, which is consistent with the current findings. Statistics show that old age is a risk factor for both contracting and passing away from this disease (33). Most of the patients had at least one underlying disease, notably the patients who passed away, which is consistent with the findings of earlier research (34). All of the individuals who passed away in the Li et al. research had underlying illnesses including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and high blood pressure. This holds true for the current investigation as well (35). Many studies have demonstrated the inflammatory nature of the infection induced by COVID-19, which results in a spike in CRP and serum albumin levels in patients and is closely associated with the severity of the sickness, in light of what was previously mentioned (36-39). Inflammatory conditions alter the amount of immunological markers on the one hand, and coagulation pathways on the other (40).

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this clinical trial demonstrated that the clinical categorization of COVID-19 patients can utilize D-dimer blood level; however, this is not a precise and reliable biomarker. For patients with COVID-19, the level of D-dimer may be the best indication of the probability of mortality. After being grouped based on D-dimer value, age, male gender, and symptoms like shortness of breath and underlying illnesses like high blood pressure and diabetes have become effective factors on D-dimer value, which impacts patients' prognoses. Patients with COVID-19 are more susceptible to death due to the aforementioned risk factors. Therefore, it can be said that even though the D-dimer measurement test is not considered to be a reliable indicator of a patient's death probability, dynamic monitoring of D-dimer levels allows for the early detection of thrombotic complications, the implementation of preventative measures to lower the risk of thromboembolism and the risk of bleeding in secondary fibrinolysis of DIC, and ultimately the decrease of the COVID-19 mortality rate. While the statistical population and the examined indicators were both small, future research that generalizes by employing a bigger population and looking at additional factors would undoubtedly provide the circumstances for producing far more robust conclusions.